History of the Museum

That was good enough for the Spalding Commission, which came to its conclusion in 1907.

Three decades later, Cooperstown philanthropist Stephen C. Clark – seeking a way to celebrate and protect the National Pastime as well as an economic engine for Cooperstown – asked National League president Ford C. Frick if he would support the establishment of a Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. The idea was welcomed, and in 1936 the inaugural Hall of Fame class of Ty Cobb, Walter Johnson, Christy Mathewson, Babe Ruth and Honus Wagner was elected.

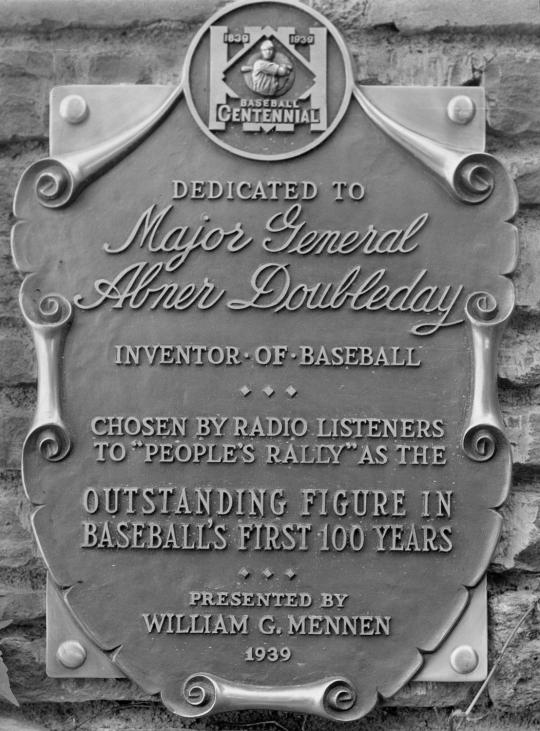

Three years later, the Hall of Fame building officially opened in Cooperstown as all of baseball paused to honor what was called “Baseball’s Centennial” and as the first four Hall of Fame classes were inducted. To mark the occasion, Time Magazine wrote: “The world will little note nor long remember what (Doubleday) did at Gettysburg, but it can never forget what he did at Cooperstown.” In the years since, The Doubleday Myth has been refuted. Doubleday himself was at West Point in 1839. Yet The Myth has become strong enough that the facts alone do not deter the spirit of Cooperstown. The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, surely the most well-known sports shrine in the world, continues to thrive in the town where baseball’s pulse beats the strongest.

But in the years following the opening of the Hall of Fame on June 12, 1939, the Museum has become much more than just home to baseball’s biggest stars. The Hall of Fame is the keeper of the game.

The Hall of Fame’s collections contain more than 40,000 three-dimensional artifacts – such as bats, balls, gloves and uniforms – donated by players and fans who want to see history preserved. The Museum’s curators use the artifacts – whose number grows by about 400 each year – to tell the story of the National Pastime through exhibits.

The Museum itself is a melding of five buildings sewn together via several renovation and expansion programs. Today, the Museum easily accommodates more than 3,000 visitors per day during the peak season.

The artifact collection is housed in climate-controlled rooms to protect the delicate leather, fabric and wood materials used in baseball. The Museum promises – in exchange for the donation of an artifact – to care for an item in perpetuity, which means the effects of temperature and humidity must be constantly regulated. The Museum’s first accessioned item was the “Doubleday Baseball”, which was discovered in a farmhouse in nearby Fly Creek, N.Y., in 1935 and dates to the 19th Century.

Then in 1937, Cy Young – elected to the Hall of Fame that year in the second year of voting – generously donated several artifacts, including the 1908 ball from his 500th win and the 1911 uniform he wore with the Boston Braves. Young’s donations generated new offers from other players as well as fans.

Thousands of fans attended the opening of the Hall of Fame on June 12, 1939, and that same year another Cooperstown tradition was started with the launch of the annual Hall of Fame Game. For 70 years, the Hall of Fame Game became an annual celebration of the game as two Major League Baseball teams played an annual exhibition contest at Doubleday Field in Cooperstown. Though the game was discontinued in 2008, the legends live on with the advent of the Hall of Fame Classic, an annual event over Memorial Day Weekend featuring Hall of Famers and former major leaguers at historic Doubleday Field.

The field itself dates back to 1920, and the first grandstand was built in 1924. Thanks to Works Progress Administration money during the Great Depression, Doubleday Field was expanded again in 1934. Today, the field is occupied non-stop during the spring, summer and fall as high school athletes, collegiate summer league stars and recreational league players savor the chance to play on hallowed ground.

As an educational institution, the Museum offers outreach programs for audiences of all ages. Through virtual classroom technology, Cooperstown is transported to schools across the country with videoconference lessons featuring any one of 16 learning modules.