- Home

- Our Stories

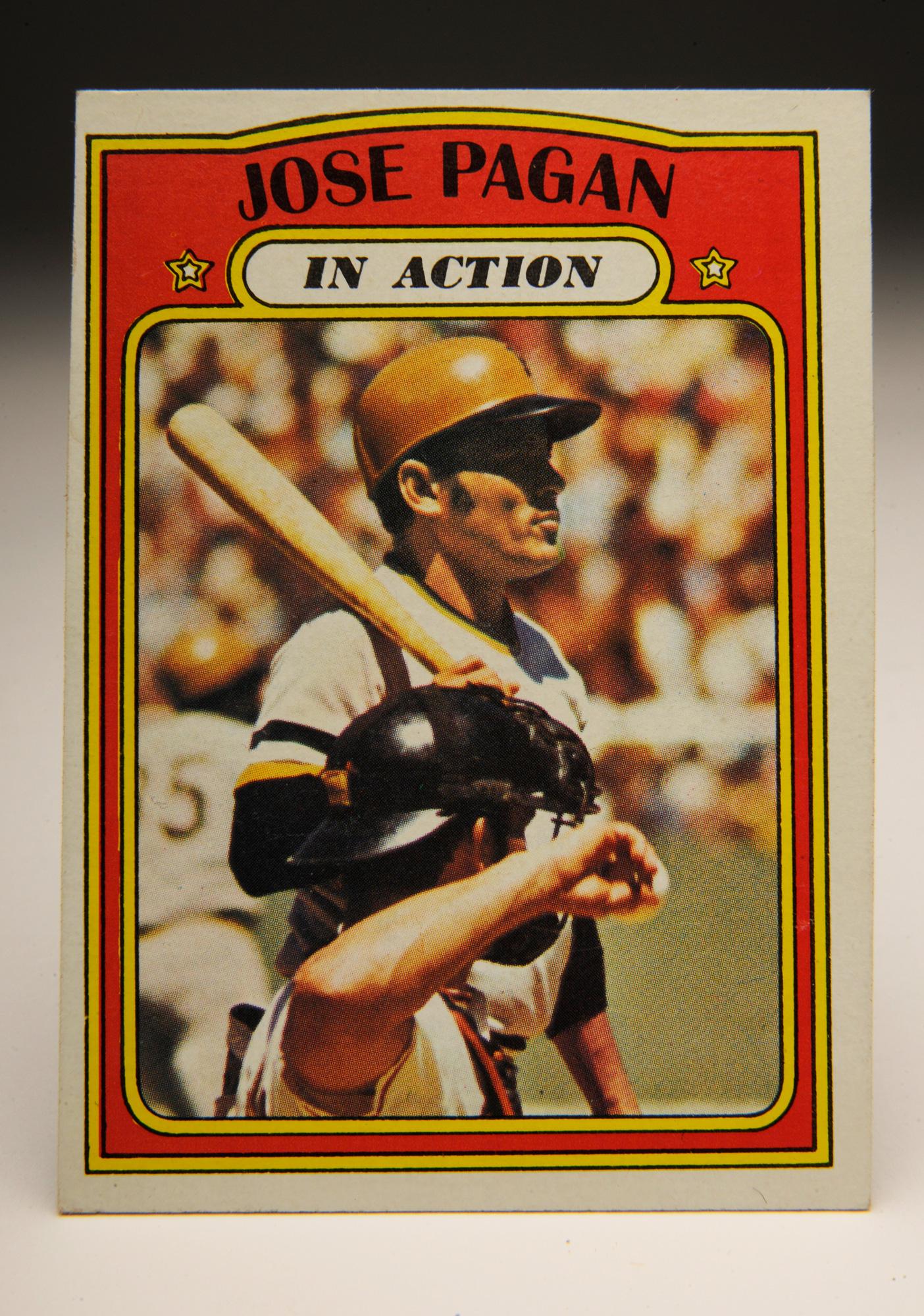

- #CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jose Pagan

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jose Pagan

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Jose Pagan might have seemed like an odd choice for Topps to highlight as part of its “In Action” series in 1972, but as young collectors, we appreciated seeing anyone in an action shot. It didn't matter if it was a backup catcher like Bob Barton or Pat Corrales or a journeyman like Curt Blefary.

At the time, we were used to most players being featured in profile or otherwise posed shots on baseball cards; an action photograph was something that we treated like gold. Topps had introduced action shots onto cards only one year earlier, so it was still a novelty, something that created a stir when we could see a player photographed while in an actual game.

On the surface, Jose Pagan was only a utility infielder for the Pittsburgh Pirates at the time of this card’s release. He platooned with Richie Hebner at third base and came off the bench as a pinch-hitter. Once again, he appeared to be nothing special. But then I learned the full story of Pagan – and how he could have become the first Latino to serve as a fulltime manager in the major leagues.

Though he’s been long overshadowed by Roberto Clemente and Steve Blass, Pagan was one of the other heroes for the Pirates in their stunning 1971 World Series upset of the Baltimore Orioles. In Game 7, Pagan stroked a double against Mike Cuellar, scoring Willie Stargell with one of only two runs for the Pirates that day. The Pirates needed both of those runs, as they squeezed by the O’s, 2-1. In other words, they might not have won Game 7 without Pagan.

In 1972, Pagan would come to bat only 127 times, his lowest full-season total in a Pirates uniform. He played decently when called up, batting .252 with three home runs in 127 at-bats. After the season, Pagan expressed unhappiness over the lack of playing time and indicated that he would prefer a trade to a team in the American League, where he might be able to find some additional time under the new designated hitter rule.

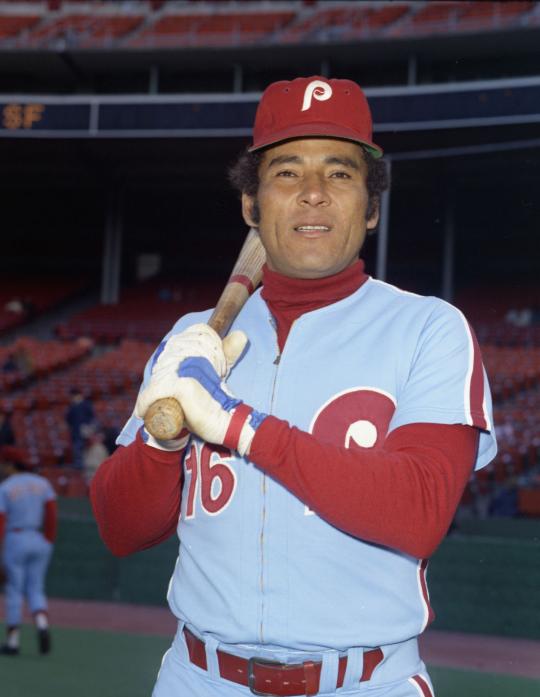

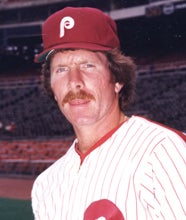

The Pirates couldn’t find a trade partner, but on October 24, they officially released Pagan, while offering him a managerial position in their farm system. Instead wanting to play at least one more season, Pagan decided to sign a player contract with the Philadelphia Phillies.

The Phillies planned to use Pagan as a backup and tutor to a promising young third baseman named Mike Schmidt. The Phillies also decided to room Pagan with another youngster, first baseman and fellow Puerto Rican Willie Montanez, who had suffered though a “sophomore slump” in 1972 and had struggled to fit in on a Phillies team that featured no other Spanish-speaking players.

Pagan played very little for the Phillies in 1973, compiling an average of just .205 in only 78 at-bats. On August 16, the last-place Phillies waived Pagan and announced plans to make him a full-time coach. Although he hadn’t hit much, the Phillies took a liking to Pagan, as just about everyone did. Several Phillies players credited Pagan with helping to improve the play of both Montanez and late-blooming outfielder Bill Robinson.

In Pagan, both the Phillies and Pirates had come to appreciate the ultimate “thinking man’s” bench player, one who fancied himself a future field manager after his playing days. He wanted to become the first Puerto Rican to manage in the big leagues. He also hoped to become the first Latino to earn a fulltime managing job, years after Cuban-born Mike Gonzalez had become an interim manager with the St. Louis Cardinals.

During a 1971 interview with the Sporting News, Pagan had revealed that he often “managed” games in his own mind from the Pirates’ bench. “I think to myself the type move I might make in a certain situation,” Pagan explained. “I think that’s common among ballplayers, especially those who are thinking of staying in the game. I think it’s important for a manager to be an inning ahead in his thinking during the game.”

Pagan wasn’t alone in believing that he could manage. The Pirates’ manager at the time, Danny Murtaugh, had already touted Pagan as an excellent choice to lead a major league ballclub in the future. “Pagan has the qualities to make a good manager,” Murtaugh once told Pittsburgh sportswriter Charley Feeney. “Jose has knowledge of the game. He can communicate with players and he has a good personality.”

Although Murtaugh didn’t bring up the racial angle of the issue, Pagan was clearly a candidate to become one of the first minority managers in major league history. The veteran third baseman was highly qualified for such a distinction, on several fronts. First off, Pagan had played the game from two different perspectives, first as a starting shortstop and then as a bench player. He had studied successful managers like Murtaugh with the Pirates, and Bill Rigney and Alvin Dark with the Giants.

Although he hailed from Puerto Rico, Pagan spoke English well enough to communicate with American-born players. As a bonus, Pagan’s ability to speak Spanish helped him relate to one of the game’s fastest growing constituencies, the Latino ballplayer. Only one factor seemed to detract from Pagan’s candidacy: He lacked the big-name appeal of a Frank Robinson, or an Ernie Banks, or Maury Wills. They were the three African-American stars who had been mentioned most often as candidates to become the first black manager in the major leagues.

The backs of the 1972 Action cards featured pieces to a variety of puzzles. One of the 1972 puzzles depicted Tony Oliva, the starting right fielder for the Minnesota Twins and the 1971 American League batting champion. Oliva was also coming off an All-Star Game selection in 1971. Unfortunately, knee injuries limited Oliva to only 10 games and 28 at-bats in 1972.

After finishing out the 1973 season as a coach with the Phillies, Pagan returned to the Pirates’ organization the following spring, when the team named him as third base coach to replace Bill Mazeroski. Pagan served as a third base, first base and infield coach until October of 1978, when the Pirates released him.

Highly respected for his knowledge of the game, Pagan managed successfully in the Puerto Rican Winter League, but received no offers from big league teams. Pagan watched as other black and Latino managerial candidates, like Frank Robinson and eventually Cito Gaston and Felipe Alou, earned opportunities to manage. Pagan realized that he himself would never receive the chance and decided to give up the profession entirely.

In 2011, Pagan died at the age of 76, a victim of Alzheimer’s disease. It was an especially cruel irony for a man who was so intelligent, dying from a disease that attacks the mind. Upon learning of his death, several of his former teammates, including Alou and Orlando Cepeda, praised Pagan for his toughness and his qualities as a “gamer.”

Would Pagan have been successful as a big league manager? It’s hard to say with certainty, but there is little doubt of this: Pagan possessed all of the necessary qualifications. He had the strategic intelligence, the ability to communicate in both English and Spanish, the toughness, and the experience of playing for a world championship team, the team that won it all in 1971.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Support the Hall of Fame

Related Stories

1965 Hall of Fame Game

1975 Hall of Fame Game

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jose Pagan

Chip off the Block

#CardCorner: 1990 Score Lance McCullers

Rickey Henderson’s two RBI lead A’s to 11th straight win to start 1981 season

From Monterrey’s Salón de la Fama to Cooperstown’s Hall of Fame

The National Baseball Hall of Fame Remembers Yogi Berra

Museum Partners with Artist Bill Purdom for 75th Anniversary Artwork

01.01.2023

BL-175.2003, Folder 2, Corr01c

01.01.2023

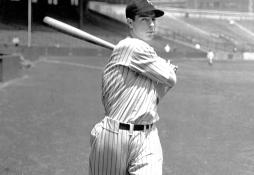

Joe DiMaggio makes his big league debut, recording three hits in the Yankees’ win

01.01.2023