- Home

- Our Stories

- Lou Brock and Hoyt Wilhelm elected to the Hall of Fame

Lou Brock and Hoyt Wilhelm elected to the Hall of Fame

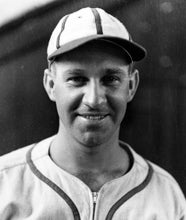

Many baseball fans point to the home run and the strikeout as the game’s most consistently thrilling moments. But on Jan. 7, 1985 two players who perfected two unpredictable aspects of the game became exciting additions to the Hall of Fame family.

That’s when St. Louis Cardinals’ master base stealer, Lou Brock, and baseball’s knuckleball king, Hoyt Wilhelm, were elected to the Hall of Fame by the Baseball Writers’ Association of America.

Brock was signed by Negro Leagues legend Buck O’Neil, then a scout, by the Chicago Cubs in 1959. While he possessed great speed, Brock struggled during his first three major league seasons until he was traded to the Cardinals midway through the 1964 campaign.

When Redbirds manager Johnny Keane gave him the green light on the basepaths, Brock responded by batting .348 and stealing 33 bases in the season’s final 103 games. He would be a key player in the Cardinals’ World Series win over the Yankees in the 1964 Fall Classic.

Brock’s triumph in 1964 was just the beginning. He went on to lead the National League eight times in stolen bases and twice in runs scored, all while inspiring a new focus on base running among general managers.

“People equate stealing a base to winning a game,” Brock would later say. “They don’t equate a home run or a single to winning a game. A stolen base is designed to go from one base to another. It’s part of the game.”

In 1974, at age 35, Brock set a major league record with 118 steals. Three years later, Brock eclipsed Hall of Famer Ty Cobb’s all-time mark when he stole the 893rd base of his career. When Brock retired in 1979, the six-time All-Star finished with a .293 batting average and 938 stolen bases – which remains the second-highest total in baseball history.

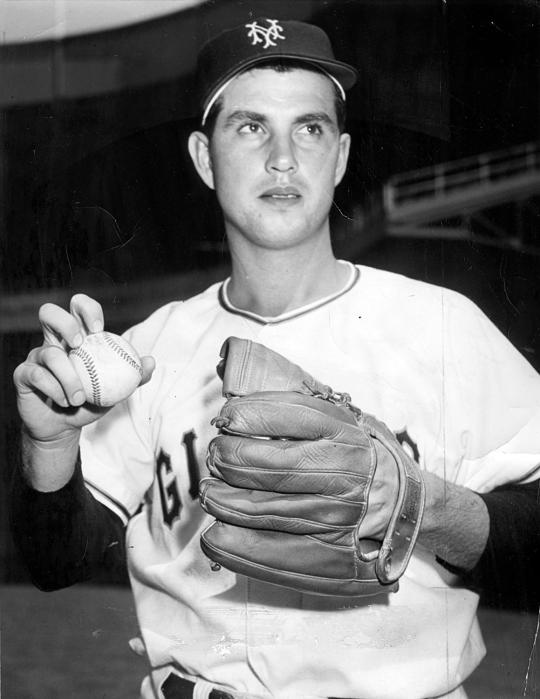

While Brock broke into the majors at age 22, Wilhelm pitched for 10 years in the minor leagues before finally receiving his big league chance at age 29. He was once released by a Class D team in Mooresville, N.C., and had even suffered shrapnel wounds in his pitching arm while fighting in the Battle of the Bulge during World War II.

Wilhelm’s inauspicious start, however, simply made the rest of his career all the more remarkable. Though he started just 52 games in his career, Wilhelm pitched for nine teams over 21 major league seasons and set the all-time record at the time by pitching in 1,070 total games. He compiled 14 seasons with an ERA under 3.00 and became the first pitcher to win ERA titles in both leagues in 1959.

They key to Wilhelm’s longevity was his chief weapon: The knuckleball. Garnering nicknames like “The Moth,” “The Iron Butterfly,” and “The Dancer” from teammates and opponents alike, Wilhelm’s pitch was as unpredictable as it was effective.

“It was easier to catch a mouse in the dark,” wrote Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray. “Everybody knew it’s coming, but it’s like knowing an atom bomb or an earthquake is coming. There’s not much you can do about it when it gets there.”

Brock became the 15th player to be elected on his first year on the BBWAA ballot. After coming up 13 votes shy on his seventh try in 1984, Wilhelm became the first relief pitcher in the Hall in 1985.

“I think that’s the ultimate for any player that’s played a few years in the big leagues,” Wilhelm said upon his election. “It’s a great thing.”

Later that year in Cooperstown, with 22 Hall of Famers in attendance, Brock delivered an emotional speech detailing his journey from poverty and discrimination in his hometown of Collinston, La. He cited a radio broadcast of a game between the Cardinals and Brooklyn Dodgers, featuring Hall of Famer Jackie Robinson, which changed his life forever.

“I was a 9-year-old in a Southern town,” Brock recalled. “Jim Crow was king. I was searching the dial of an old Philco radio and I heard (Ford C. Frick Award winners) Harry Caray and Jack Buck, and I felt pride in being alive. The baseball field was my fantasy of what life offered.”

Matt Kelly was the fall public relations intern at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Support the Hall of Fame

Related Stories

Robin Yount and Dave Winfield were picked No. 3 and No. 4 overall in the MLB Draft

Hall of Fame to Salute Baseball’s Last Half Century in ‘Whole New Ballgame’

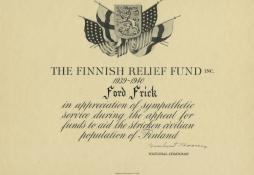

When Baseball Stepped to the Plate for Finns

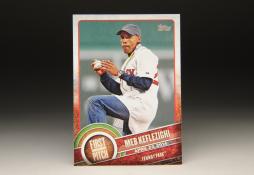

#PopUps: Meb's First Pitch

Hall of Famers PLAY Ball in Cooperstown in Support of Museum’s Education Programs

1996 Hall of Fame Game

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Pagliarulo

Playing it Cool

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Mets Maulers