- Home

- Our Stories

- ‘Manassa Mauler’ and ‘Sultan of Swat’ ruled the 1920’s

‘Manassa Mauler’ and ‘Sultan of Swat’ ruled the 1920’s

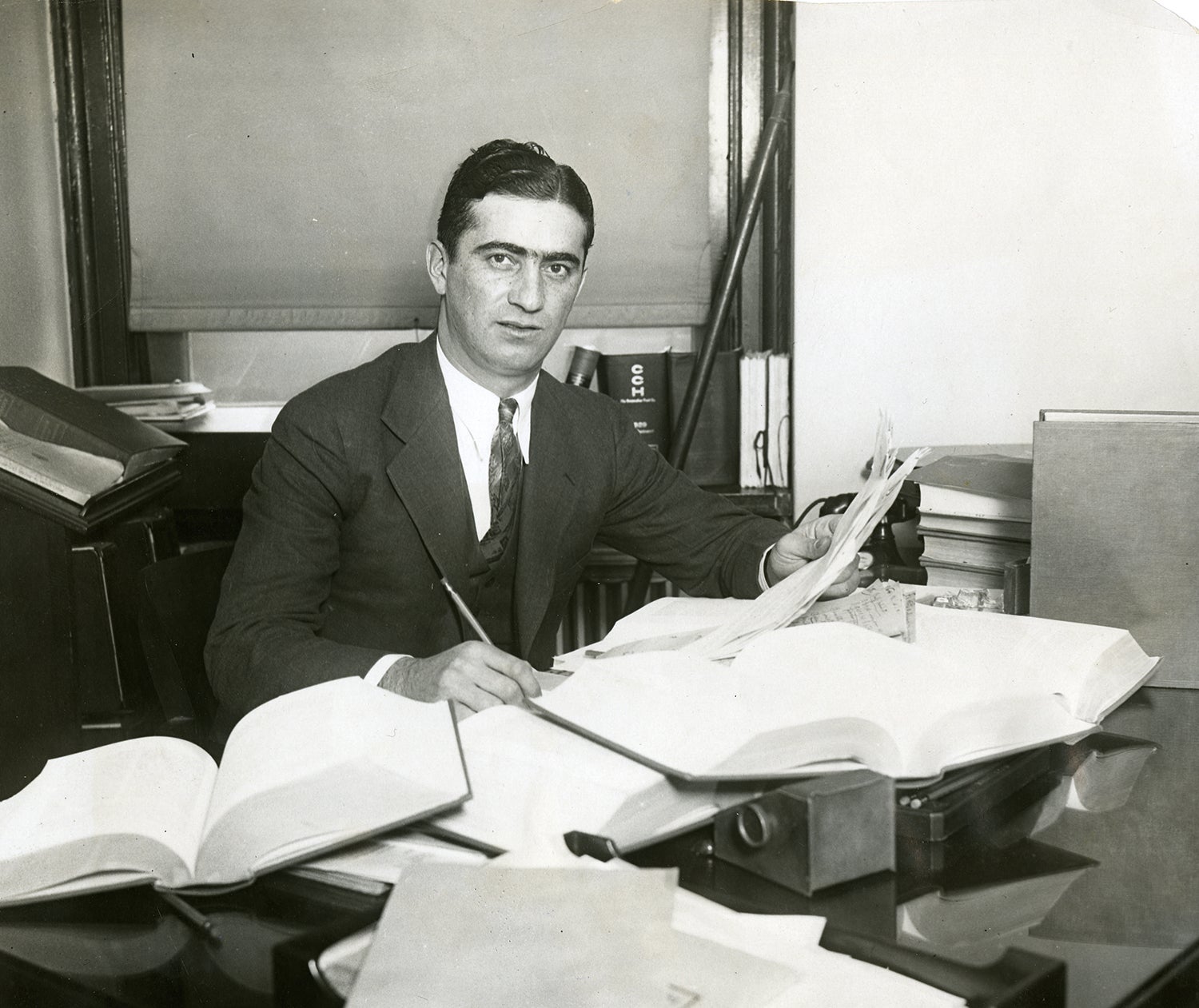

In the 1920’s, there were no bigger sports icons in the world than Jack Dempsey and Babe Ruth. The two were “larger than life figures” who were recognized by almost anyone in the civilized world.

Dempsey went by the nickname “Manassa Mauler” because of his brawler-like fighting. He would win his first heavyweight championship belt on July 4, 1919, when he knocked out his much larger opponent, the heavily-favored Jess Willard. Willard stood 6-foot-6 and hovered over the 6-foot-1 Dempsey.

Dempsey used his speed and aggressiveness to knock out the much bigger man in three rounds. He would defend his title successively five times in the next six years.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

The Mauler had his most famous title defense in 1923 at Ruth’s old neighborhood, the Polo Grounds. Dempsey met Luis Angel Firpo. In the first round, Dempsey knocked down Firpo several times in the round. Firpo then knocked him out of the ring. The referee counted to four before Dempsey returned to the ring. Dempsey then knocked down Firpo twice in round two before the referee stopped the fight and declared Dempsey the winner.

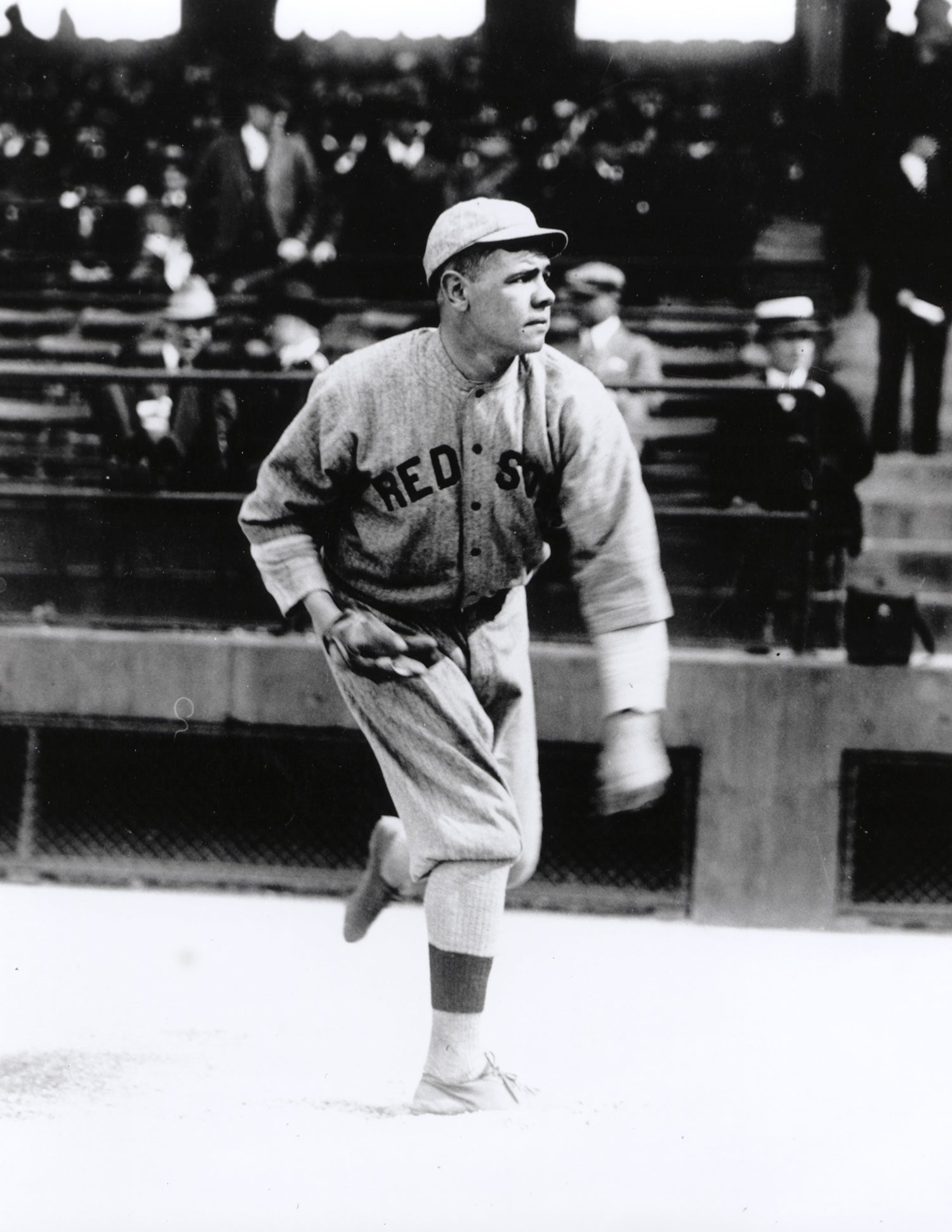

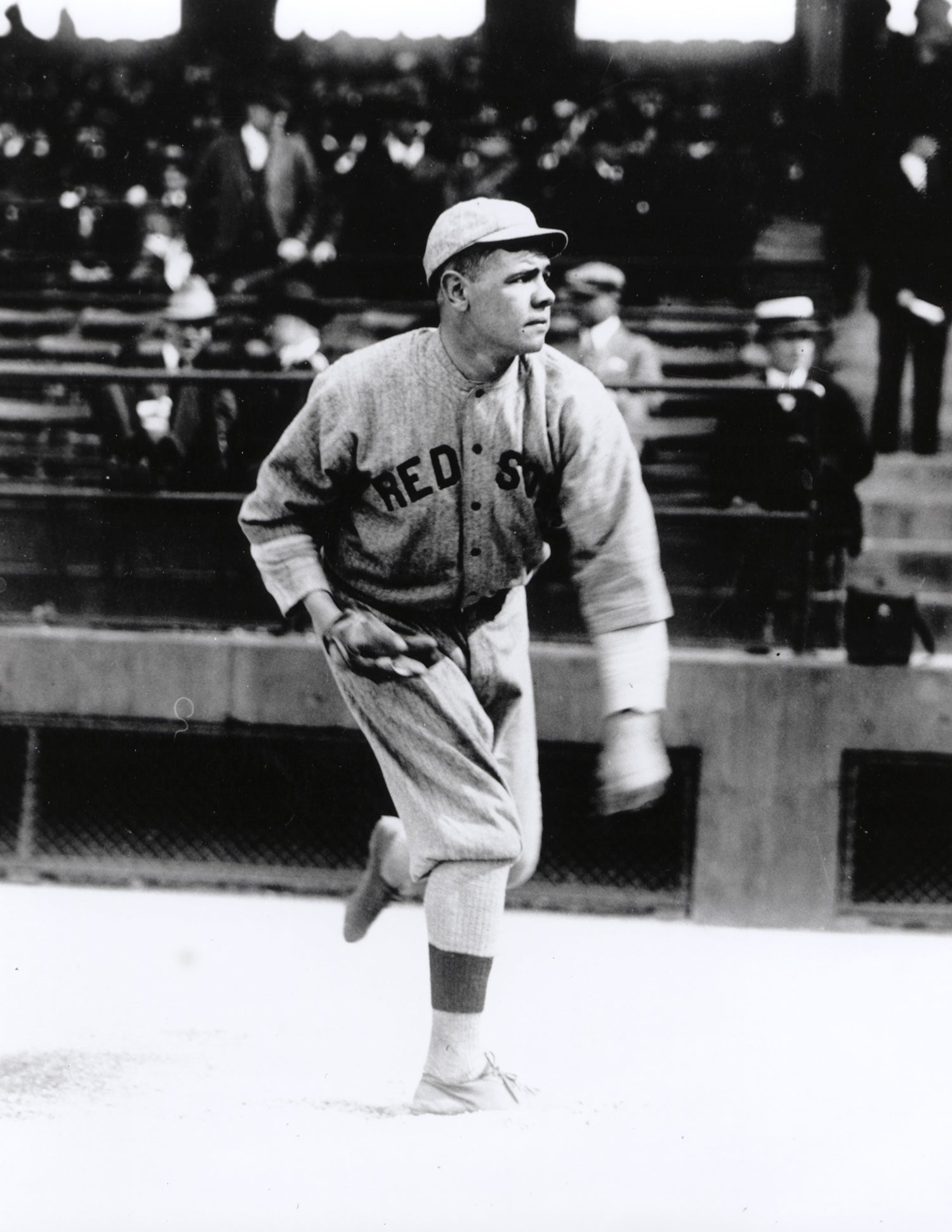

Four years earlier, Babe Ruth was sold to the New York Yankees by the Boston Red Sox. When Ruth hit New York, he became a huge hit almost immediately. In 1920, he hit 54 home runs. He hit more home runs than every other team in the American League that year. His 60 home runs in 1927 held up as the most ever in one season until Roger Maris hit 61 in 1961.

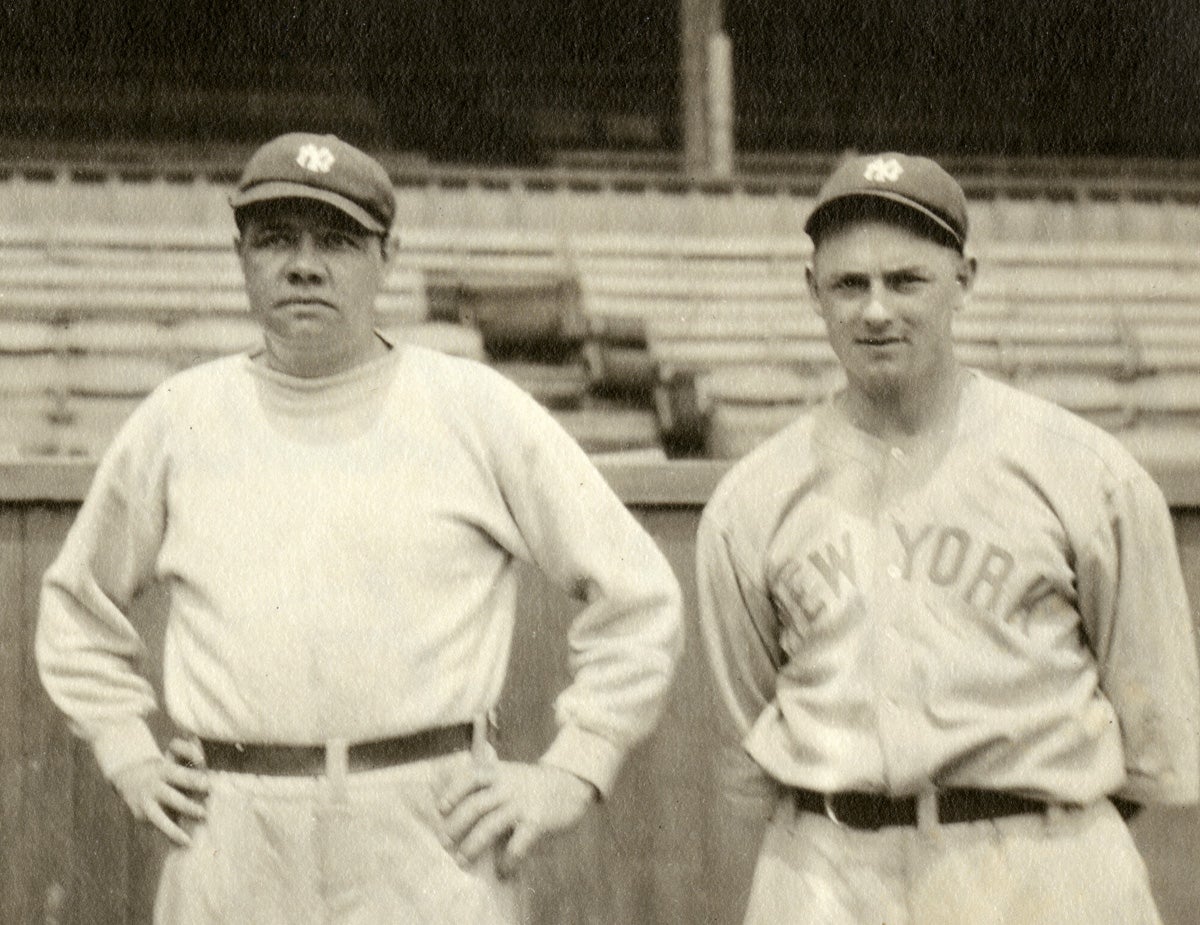

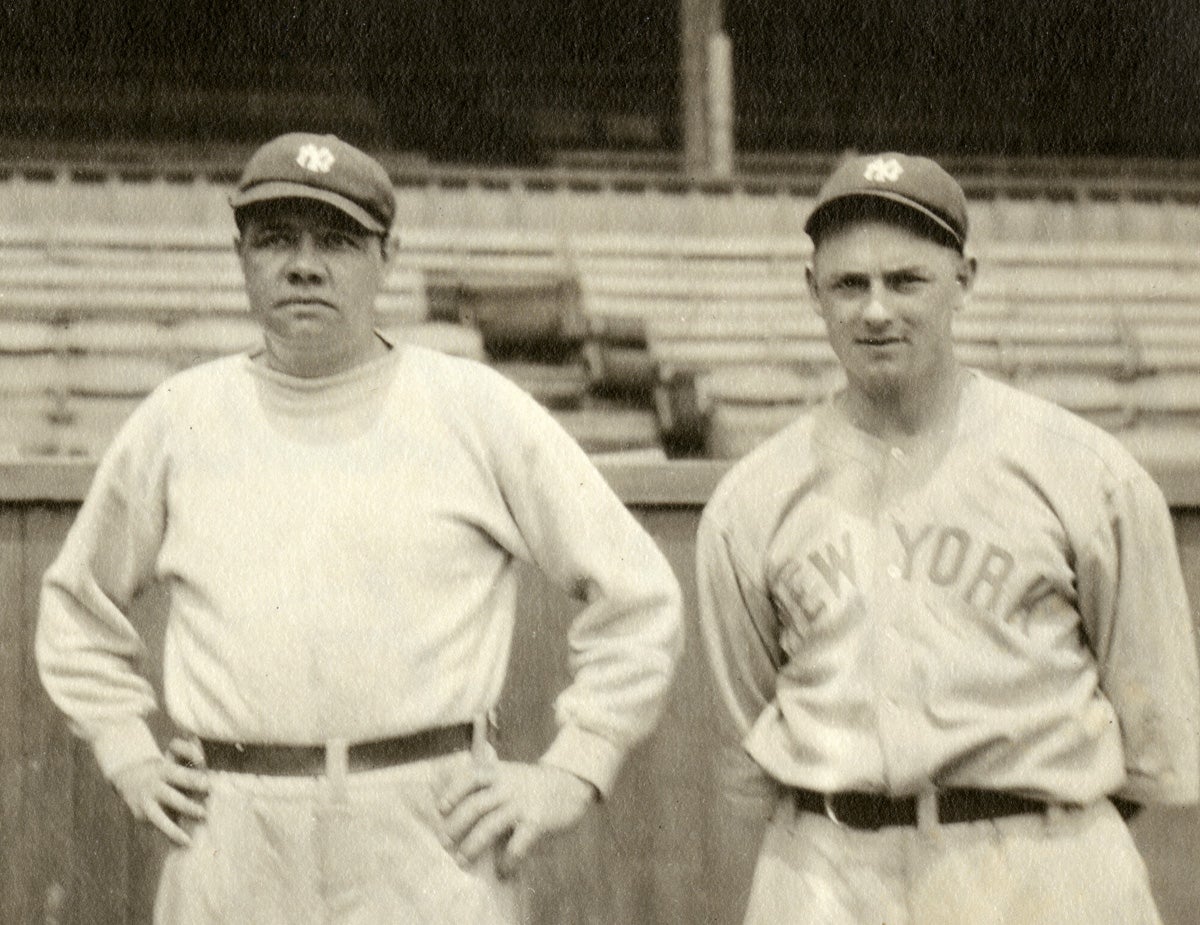

Ruth and Dempsey were great friends who often socialized with each other. Whenever they appeared together, large crowds gathered just to catch a glimpse of the legends.

In 1922, Ruth was suspended for the first six weeks of the season for barnstorming during the winter. Commissioner Landis had put into play a rule that no player who played in the World Series could barnstorm during that same year. Once the suspension was over, Ruth endured a slow start. Some skeptics said that he would never be the same again.

Dempsey felt differently. He was quoted as saying, “I never lost confidence in my friend. I knew that Babe had the stuff and that it would only be a matter of time when he would be hitting them out as well as ever.”

Ruth appreciated the words from his good friend and eventually warmed up at the plate, finishing the season with 35 homers and 96 RBI. Meanwhile, Landis’ barnstorming rule was dropped that July.

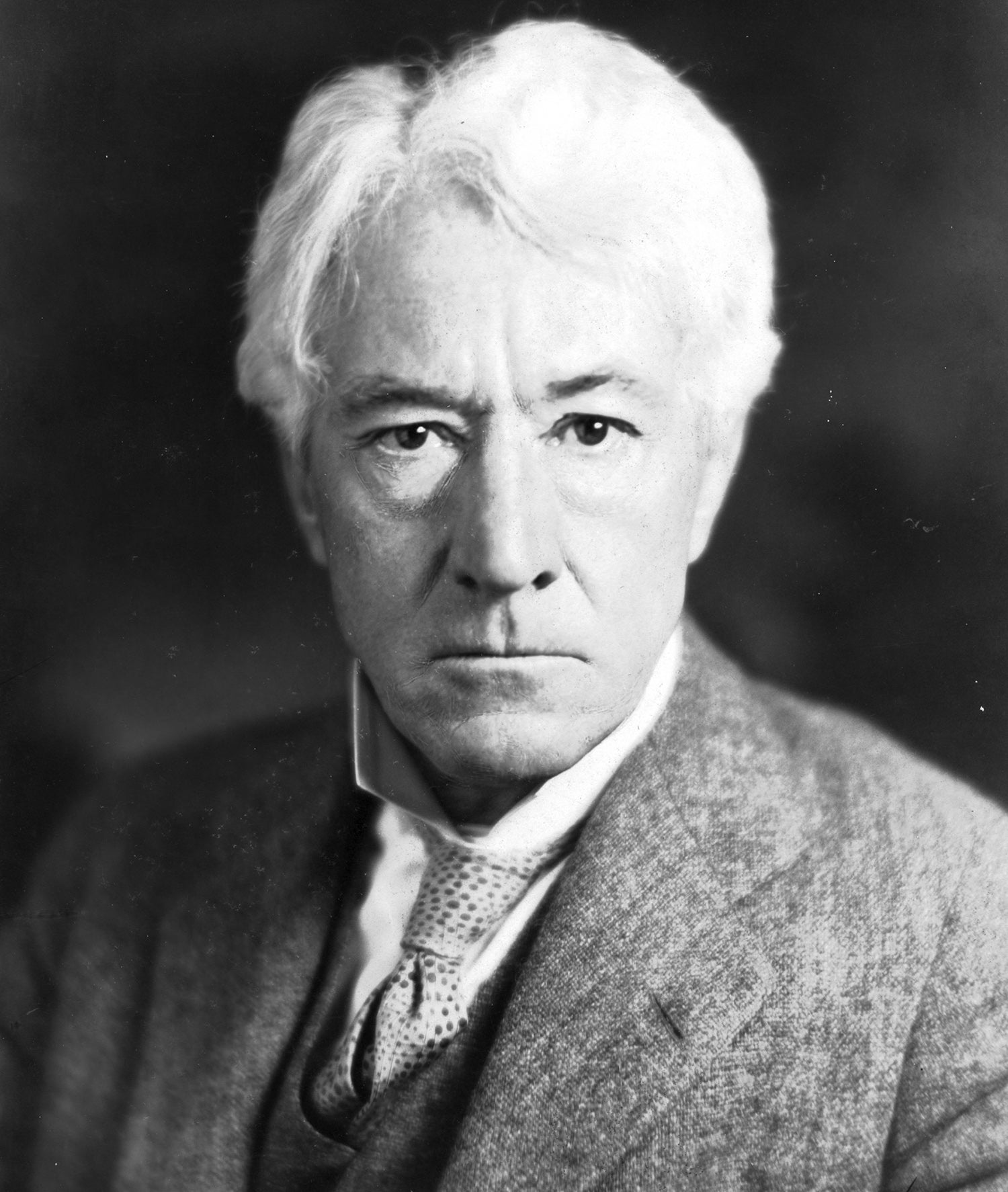

Five years later, Dempsey was feeling down and depressed after losing a recent title match to Gene Tunney in 1926. It was his good friend, Babe, who talked him in to taking a rematch. “Does the title mean anything to you?” said Ruth.

“It means everything,” said Dempsey.

“Then get it back,” urged Ruth. “The public is what keeps you going. Look at me, I never felt better. ”

On Sept. 22, 1927 Dempsey had his rematch with Tunney. It was to be known as the “long count” match. In the seventh round, Dempsey knocked down Tunney. The referee did not start the count right away because Dempsey was not in a neutral corner. It was a fairly new rule, one that Dempsey had forgotten about. As a result, Tunney received an extra five seconds, rebounded from the knockdown, and won the fight. It would be Dempsey’s last professional fight.

In 1929, Dempsey would meet Ruth in the ring. It was an exhibition bout in Palm Beach, Fla. Tickets were said to have gone as high as $5,000 just to see the two icons. In the first round, Dempsey put on a show with his good friend. Dempsey avoided all of the punches from Ruth. He took it easy on the Babe, but easily won the round.

When the bell rang for the second round, Babe came charging out after the former champ with a bat in his hand. Dempsey fled the ring. The crowd loved the spectacle.

The 1920’s would become known as the “Roaring 20’s.” From a sporting perspective, these two legends played their part in making the decade entertaining. Dempsey and Ruth would remain great friends until The Babe’s death in 1948.

John Horne is the coordinator of rights and reproductions at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

#ShortStops: The Sultan of Southpaw Shutouts

#Shortstops: Waite Hoyt Remembers The Babe

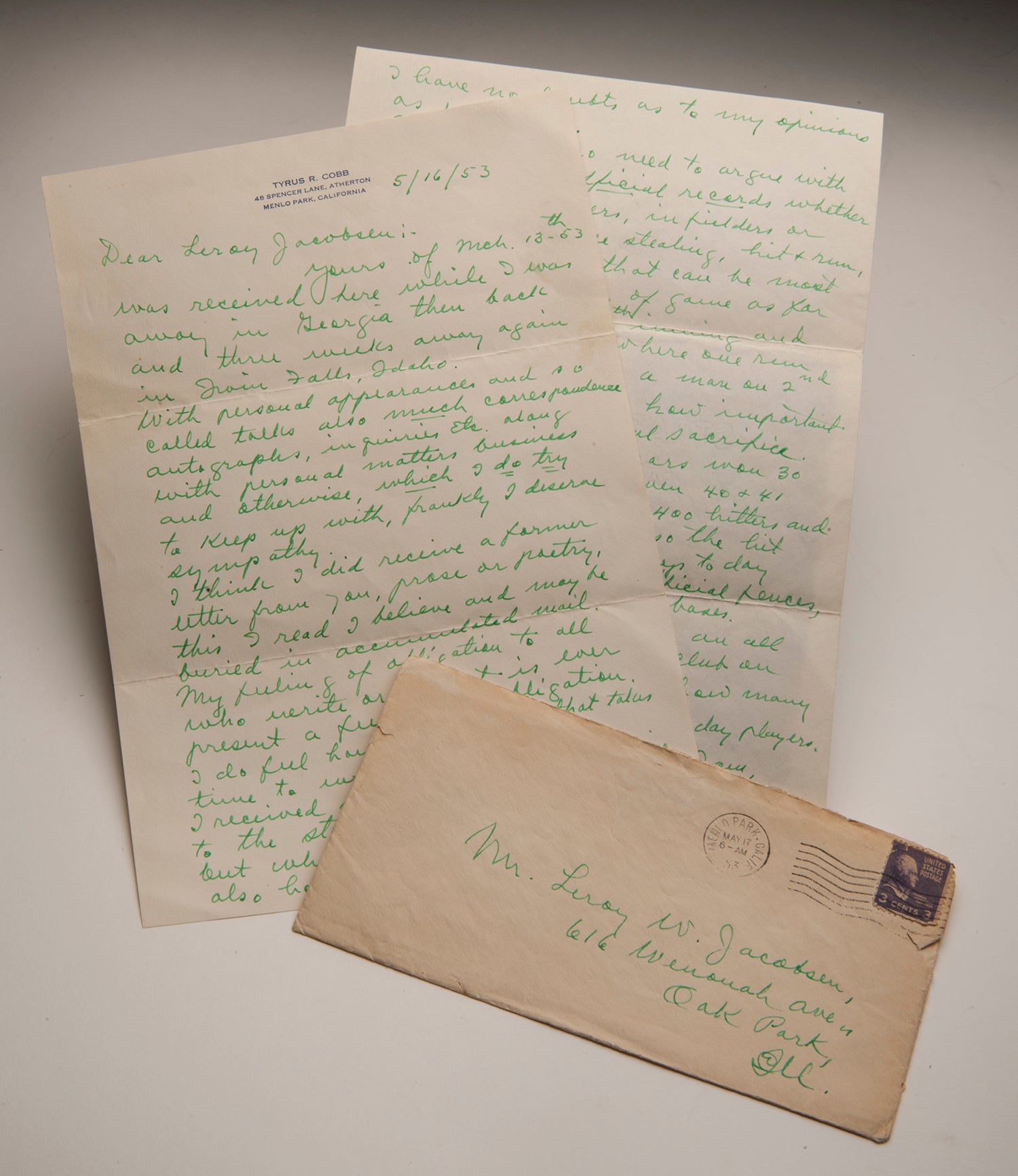

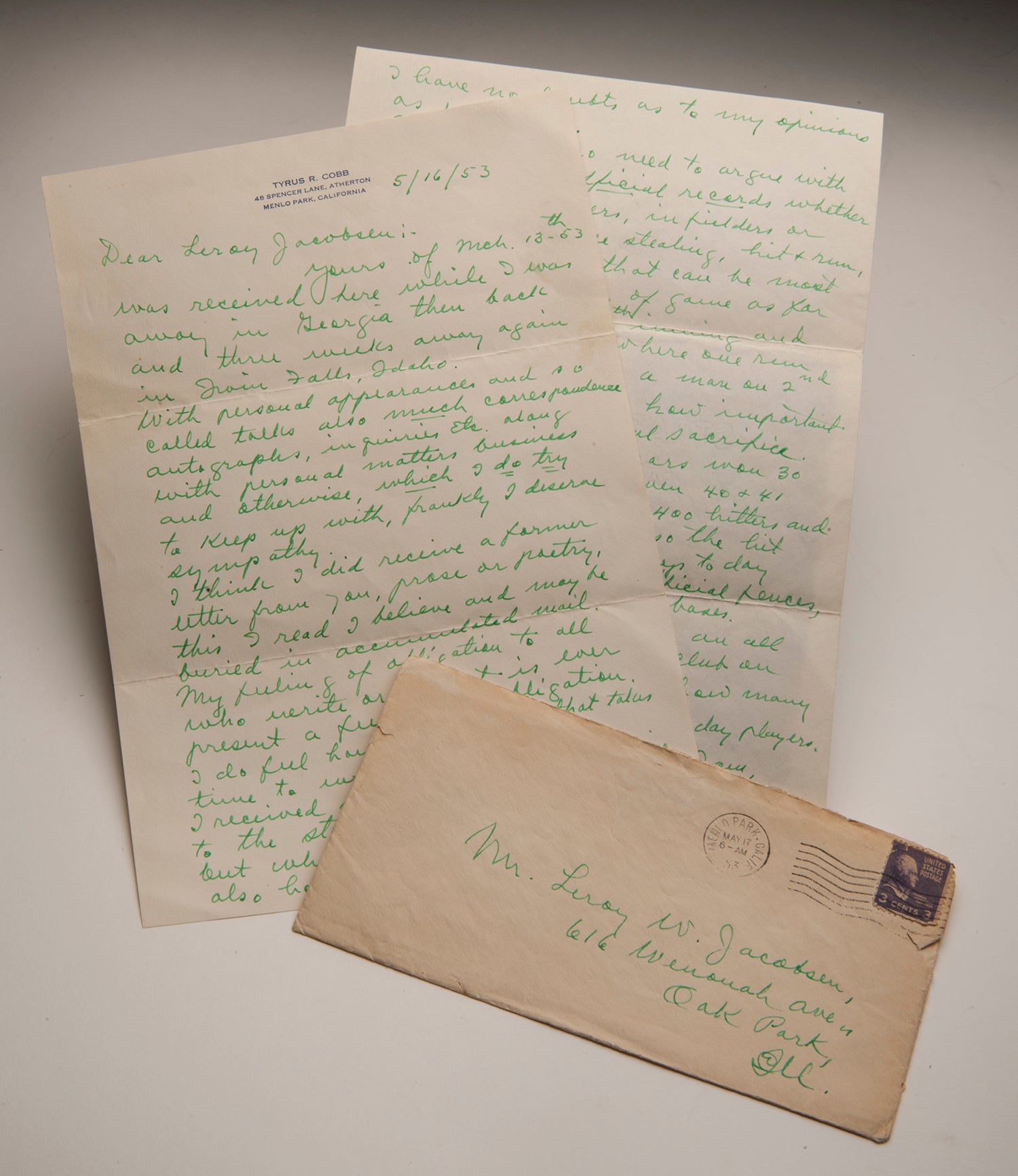

#Shortstops: Letters from Ty Cobb

#Shortstops: Moe Berg’s life in baseball

#ShortStops: The Sultan of Southpaw Shutouts

#Shortstops: Waite Hoyt Remembers The Babe

#Shortstops: Letters from Ty Cobb