“I think Gehrig cared a lot about his streak, and I think he probably cared about it from his rookie season.”

- Home

- Our Stories

- Iron Horse, Steel Will

Iron Horse, Steel Will

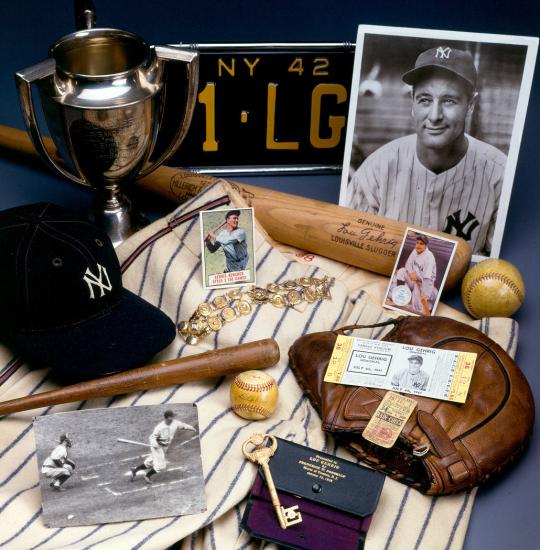

Though more than seven decades have passed since the death of Lou Gehrig, the life of baseball’s Iron Horse still resonates with fans of the national pastime. Whether it is the result of his immense skill on the diamond or his tragic death at the age of 37 from a disease that now bears his name, his lifetime of superlatives consistently is topped by a hard-fought unwillingness to miss a game.

Today, Gehrig’s streak stands as a permanent monument to perseverance. And at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, Gehrig’s contributions on and off the field are honored through the Museum’s Character and Courage exhibit, which features statues of Roberto Clemente, Jackie Robinson and Gehrig.

But during the streak, several long-forgotten close calls nearly stopped Gehrig’s path to immortality. Only Gehrig’s determination, it seems, kept history alive.

A strapping first baseman with the fabled New York Yankees from 1923 to 1939, Gehrig’s list accomplishments includes home run and RBI titles, a Triple Crown, World Series championships and a pair of American League Most Valuable Player awards. But it was his 2,130 consecutive games played, recorded from June 1, 1925 to April 30, 1939, that truly set him apart. The previous record of 1,307 was set by shortstop Everett Scott from 1916 to 1925, while Cal Ripken Jr., who from 1982 to 1998 played in 2,632 consecutive games, holds the current mark.

“I think Gehrig cared a lot about his streak, and I think he probably cared about it from his rookie season,” said Jonathan Eig, author of the 2005 best-seller “Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig.” “I think his durability, his strength, was really his greatest source of pride. I think this was part of his character, the reliability that he came to be associated with.

“And I think a big part of it had to do with the fact that it was something Babe Ruth couldn’t do. Babe Ruth had all the glamorous statistics, but Gehrig had his own thing. And I think later in life, when he began to resent Ruth a little bit, this one was particularly important to him because it represented the one true undeniable department in which he was superior to Ruth.”

Over his lengthy career, Gehrig was faced with numerous injuries and handicaps that could have sent him to the sidelines, but he courageously played through pain.

Gehrig’s endurance record threatened to end abruptly when he was struck behind the right ear by Washington pitcher Earl Whitehill on April 23, 1933. Gehrig not only stayed in the game but would score a run that inning.

As 1975 J.G. Taylor Spink Award honoree Shirley Povich wrote in the next day’s Washington Post, “Whitehill’s pitch that beaned Gehrig in the sixth would have been a safe bunt if Lou had connected with his bat instead of his head. He staggered to first base via the right-field boxes like a drunk on an escalator.”

Arguably the most serious challenge to Gehrig’s streak came when the Yankees were playing one of their farm teams in an exhibition at Norfolk, Va., on June 29, 1934. After hitting a home run in the first inning, Gehrig was struck on the crown of the head by a Ray White pitch in the second inning. According to reports, Gehrig was unconscious for five minutes.

“I have a slight headache, and there is a swelling on my head where the ball hit,” said Gehrig after the game, “but I feel all right otherwise, and will be in there tomorrow.”

In fact, Gehrig was ready to play the next day’s game in Washington when X-rays taken failed to disclose a serious injury. He even hit three successive triples, which proved, according to Povich, “that the wild pitch he took in the head at Norfolk the day before made him no more plate-shy than a starving Armenian.” But the game, which would have been Gehrig’s 1,415th consecutive, was washed away by the rain in the fifth inning before it would become official.

In a matchup at Detroit on July 13, 1934, in which Ruth would hit his 700th career home run, Gehrig would suffer so much pain in his back that he would be forced to leave in the second inning of his 1,426th consecutive game. There was speculation in the press that this “attack of lumbago” may very well spell the end to Gehrig’s record.

In order to keep his streak intact, the next game a still-suffering Gehrig, for the first time in his big league career, was listed in the starting lineup as anything but a first baseman. Designated as New York’s shortstop and leadoff hitter, he began the top of the first inning by slapping a single to right field and then gave way to a pinch-runner.

“I think it’s a type of courage to persevere and to keep yourself going and to never give up."

“To me, records mean nothing. The big thing in baseball is a man’s usefulness to his club,” said Gehrig later in the 1934 season. “But that string doesn’t mean a thing. It just happened. I never have played in a game when I was unfit. I never played when it was an effort.

“I like to play baseball, just as I like to eat. It would take something pretty serious to keep me away from the dinner table, and likewise it takes something pretty serious to keep me out of a game. Besides, I figure I owe it to the club to play as often as I can.”

But when asked about those instances in which he played only a portion of a game after injuries, Gehrig smiled and said, “Well, just figure that I ate a small meal on those days – but I ate nonetheless.”

Another close call came in the first game of a doubleheader against the Boston Red Sox on June 8, 1935. Playing in his 1,549th straight game, Gehrig, manning first base, was knocked out with a shoulder injury for several minutes after a first-inning collision with base runner Carl Reynolds. Gehrig, as he was apt to do, continued to play.

After appearing in his 1,600th consecutive contest on Aug. 8, 1935, Gehrig gave the credit to good luck.

“It’s this way. I might go out there tomorrow and get injured so badly I couldn’t play, no matter how much I wanted to. Or I might get so sick they’d cart me off to the hospital,” Gehrig said. “You’ve got to be lucky to go through even one full season of 154 championship games and about 45 exhibition games without being hurt. And you’ve got to be lucky to go jumping around the country on trains, eating in different places and drinking different kinds of water, without getting sick.”

But for Gehrig, it became apparent that overcoming broken bones, concussions, lumbago, bumps and bruises was minor compared to the effects of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), which ultimately led to is retirement from the game in 1939. He ended his streak eight games into the season, after he felt he could no longer contribute.

“The entire 1938 season, you could make a case, was the most remarkable of all Gehrig’s challenges he had to overcome because he’s basically playing much, if not all, of the season with the symptoms of ALS,” Eig said.

“I think it’s a type of courage to persevere and to keep yourself going and to never give up. Certainly when he’s facing symptoms of ALS he doesn’t know it yet. He’s clearly a sick man, a dying man, and he’s playing on,” he added. “That’s some of the greatest courage that we’ve ever seen on a baseball field, in my opinion. I think it’s right up there with what Jackie Robinson did.”

On Dec. 7, 1939, the Baseball Writers’ Association of America voted unanimously to suspend the waiting period and placed Gehrig in the National Baseball Hall of Fame immediately “to commemorate the year in which he achieved his record.”

Bill Francis is a library associate at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Red Sox trade Cy Young to Cleveland

Ready for the Weekend

Tom Seaver strikes out 10 straight Padres

Hall of Fame Weekend 2017 to Feature Inductions of Jeff Bagwell, Tim Raines, Iván Rodríguez, John Schuerholz, Bud Selig, July 28-31 in Cooperstown

Commissioner Landis frees 74 Cardinals farmhands

Caught in the Draft

BA MSS 67, Folder 15, Corr_1946_4_24

Two-time Cy Young Award-winner Gaylord Perry reflects on making history in both leagues

Dominant Dodgers

Hall of Fame to Celebrate Historic 2014 with Community Day on Sunday, Oct. 5

01.01.2023

Induction Eve Thrills Fans, Hall of Famers in Cooperstown

01.01.2023

Celebrate Hall of Fame Weekend Journey Through Inductee Memories at Legends Roundtable Event

01.01.2023