“Pedro’s probably the closest thing to a character this club had.”

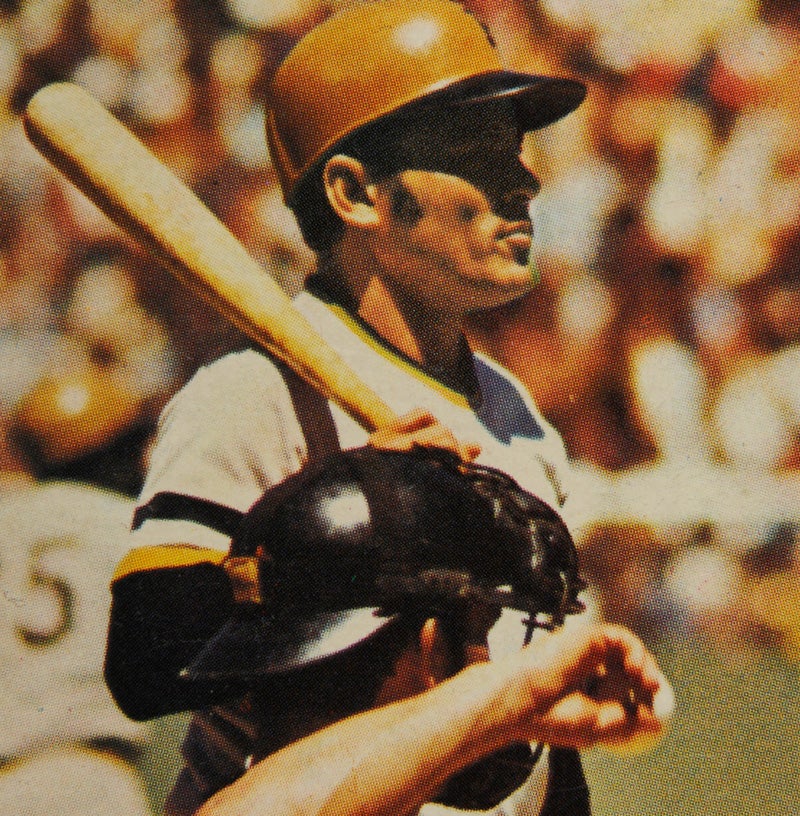

#CardCorner: 1970 Topps Pedro Borbón

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

With Halloween upon us, we inevitably start thinking about the legendary monsters who have supplied us with such great subject matter for our children’s costumes and get-ups (not to mention our own). I tend to gravitate toward the classic monsters that Universal Studios depicted in so many of their films from the 1930s, 40s, and 50s: Frankenstein, The Wolf Man, and The Creature From the Black Lagoon (AKA The Gillman). Perhaps no classic monster has become more emblematic of Halloween than the sinister Dracula, as played by the legendary Bela Lugosi, who took theaters by storm in 1931.

Of all the players in big league history, only two (at least to my knowledge) have been nicknamed “Dracula.” One is journeyman pitcher Al Cicotte, who pitched for a number of teams, including the New York Yankees, Cleveland Indians, and Houston Colt .45s, in the late 1950s and early 60s. Cicotte earned the nickname of Dracula because he liked to wear black capes (for reasons that remain elusive). Cicotte was also nicknamed “Bozo,” a moniker that does not exactly conjure up images of vampires, though it does recall a famous clown from an era long ago.

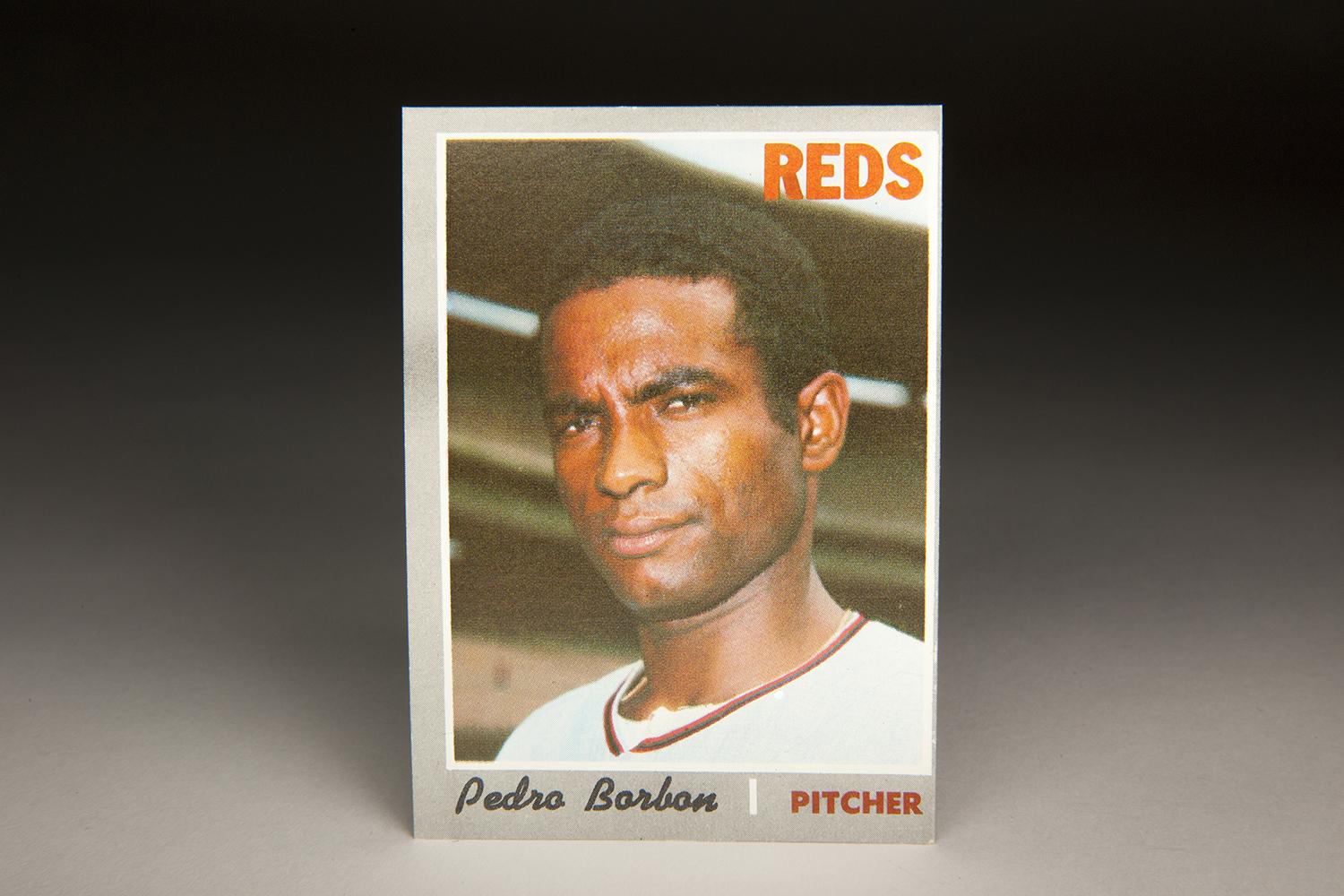

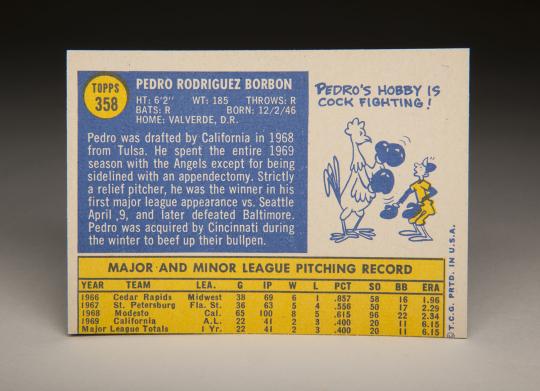

The other player called Dracula is far better known. That would be Pedro Borbón, seen here on his rookie card, issued as part of the 1970 Topps set. Borbón doesn’t look much like Dracula here, whether you’re talking about the Lugosi version, or the one played by Christopher Lee in all those Hammer movies, or the more recent version played by Gary Oldman. But Borbón does have somewhat of a fiendish expression, a combination of annoyance and perhaps even mild anger. Looking slightly mischievous, perhaps even sinister, we might say that he is ready to take a bite out of the cameraman.

Of course, that never happened here. But a few years later, Borbón did take a rather famous bite out of a baseball cap. And then he became involved in two other biting incidents, one at the ballpark and the other at a disco. Those incidents played a large role in Borbón becoming known as Dracula, or “The Dominican Dracula,” for those who prefer an even more descriptive nickname.

At the time, Borbón was considered a throw-in, an afterthought. But the Reds knew better. Their super scout, a brilliant man named Ray Shore, told general manager Bob Howsam to insist that Borbón be included in the trade. At first, it appeared that Shore had lost his mind. Borbón struggled in the spring and began the season pitching at Triple-A Indianapolis, receiving a call-up in midsummer. He then proceeded to pitch worse for the Reds than he had done for the Angels.

Realizing that Borbón needed more time, the Reds the Reds sent him back to Triple-A at the start of the 1971 season. Pitching exclusively in relief, Borbón put up his best Triple-A campaign, winning 12 of 18 decisions, with an ERA of 3.06, and good strikeout numbers. In September, the Reds brought him back to Cincy. Borbón didn’t pitch particularly well that month, but would never again return to the minor leagues.

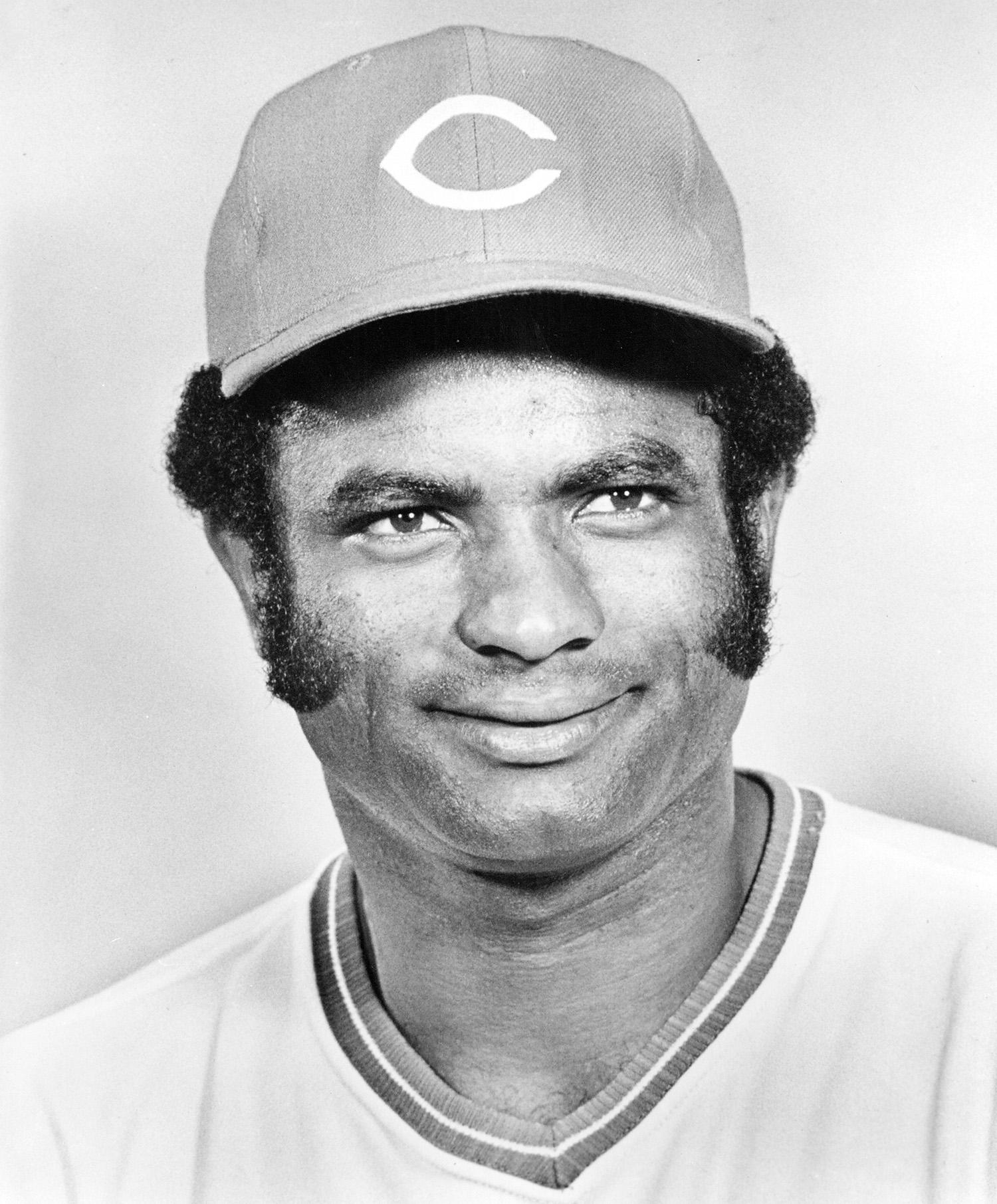

By 1972, Borbón had fully justified Shore’s faith in him. Aided by a manager who liked to go to his bullpen early and often, Borbón thrived. Future Hall of Famer Sparky Anderson, known as “Captain Hook,” called on Borbón 62 times that season and used him in every conceivable role: long relief, late-inning relief, and occasionally as a closer (or “fireman,” in 1970s vernacular). The sinkerballing Borbón logged 122 innings, put up an ERA of 3.17 and saved 11 games. Sharing fireman duties with veteran reliever Clay Carroll, Borbón emerged as one of Anderson’s most reliable relievers.

That season marked the beginning of an incredible run for Borbón. From 1972 to 1977, Borbón pitched at least 122 innings a season. His ERA never rose above 3.35 for any of those seasons. He didn’t do it with power – in fact, he never struck out more than 60 batters in a single season – but relied on a sinking fastball, a slider, and the ability to throw his pitches where he wanted.

Borbón’s workhorse abilities were also tested in pressure situations. During the span of Borbón’s tenure with them in the 1970s, the Reds won four division titles. Pitching in all four League Championship Series, he compiled an ERA of 1.26 ERA. Pressure games rarely seemed to have much of an effect on Borbón, who maintained his offbeat personality regardless of the situation.

It was during the 1973 playoffs that Borbón became involved in one of the most humorous incidents of his career. After Pete Rose’s takeout slide of Bud Harrelson, the two players began brawling, leading to an exodus of players from the dugouts and the bullpens. Borbón joined the fracas, which left him without a cap on his head. As the dust settled, Borbón noticed a cap lying on the ground. He picked it up, but then realized that it bore a New York Mets logo, and not the colors of the Reds. Rather than discard the cap, which belonged to Mets outfielder Cleon Jones, he took a bite out of it, leaving the cloth fabric with a sizeable hole in it.

Borbón did not restrict his throwing exhibitions to the regular season. Killing some time before a 1975 World Series game at Boston’s Fenway Park, Borbón decided the time was right to put on a show. Refusing to take any warmup pitches, Borbón heaved the ball over the wall in center field.

Borbón’s antics not made him a memorable figure around big league ballparks, but also in his native Dominican Republic. Borbón returned to the Dominican each winter, not just to live but to pitch winter league ball. One day, Borbón brought his pet rooster into his Dominican team’s clubhouse, creating a stir with his teammates. Knowing full well about his oddball tendencies, a few Dominican fans tried to distract him by throwing a black cat onto the playing field steering it in the general direction of the pitcher’s mound. Borbón picked up the cat as it made its way toward the mound. He then tossed the cat to the catcher.

After the game, Borbón discussed his annoyance with the stunt involving the cat. “I should have eaten it,” Borbón told a reporter in the clubhouse. “That would show them.” Thankfully, Borbón was only kidding.

Borbon also claimed to have an unusual family, which featured an incredible degree of longevity. Borbón said that some of his relatives had lived well over a century. He also bragged that his grandfather was 136 years old, one year after claiming that he was 128. Somehow, grandpa had aged eight years in 12 months!

Although Borbón’s antics often endeared him to the Cincinnati faithful, other incidents tested the patience of a conservative Reds organization. One infamous incident occurred in public, in a Cincinnati disco, during the 1979 season. Borbón and another patron of the disco began fighting. When a bouncer tried to intervene, Borbón bit him – right in the chest. Another hit for Dracula, who was ordered to pay $1,500 in damages to the bouncer.

After the 1979 disco incident, Reds general manager Dick Wagner criticized Borbón publicly. Shortly after the 1979 trading deadline of June 15, the straight-laced GM sent Borbón to the rival San Francisco Giants for reserve outfielder/third baseman Hector Cruz. Even in ridding himself of a player who could be troublesome, Wagner expressed some regret for losing a player with personality. “It is sad, in a way,” Wagner told Mark Purdy of the Cincinnati Enquirer. “Pedro’s probably the closest thing to a character this club had.” Wagner admitted that for all of Borbón’s controversy, he still liked him.

Unhappy with the trade, Borbón announced to the media that he would “call his voodoo out and put it on Cincinnati.” Unfortunately, the voodoo didn’t work in San Francisco. Borbón pitched poorly for the Giants, appeared on one Topps card wearing their colors, and then drew his release during the spring of 1980. He soon found work with the Cardinals, the team that had originally signed him out of the Dominican, but he struggled to throw strikes. With his pinpoint control gone, he received his release in May of 1980, ending his career.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Shortly after his playing days ended, Borbón’s name became nationally prominent. That’s because it was mentioned in the 1980 film, Airplane, a raucous comedy that parodied the disaster films of the 1970s. In one scene, pilot Ted Stryker hears voices in his head, one sounding like a public address announcer at a ballpark. “Pinch hitting for Pedro Borbón… Manny Mota.” Borbón loved the reference, which became a source of pride. According to his son, Pedro loved talking about the line from the movie.

After the reference in Airplane, Borbón fell out of the public spotlight for the next decade and a half, only to return during the long strike of 1994 and ’95. Borbón signed with the Reds as a replacement player, even though he was 48, hadn’t pitched in a major league since 1980, and now weighed over 240 pounds. He made two exhibition appearances for the Reds’ replacement squad, striking out one batter in his first game but making an embarrassing fielding error in the second. After throwing wildly on a bunt attempt, the Reds released him, largely because he was so out of shape.

In 2010, the Reds honored Borbón by electing him to their Hall of Fame, quite an accomplishment for a pitcher who had spent most of his career pitching in middle and set-up relief. It was a tribute to his durability, his impact on two world championship teams, and perhaps to a lesser extent, his colorful personality that always made life with the Reds so interesting.

Sadly, the news of Borbón’s election to the Reds’ Hall of Fame turned out to be the last time that he made news within baseball. Only two years later, in June of 2012, Borbón died at his Texas home after a battle with cancer. He was 65.

With that, baseball lost its version of Dracula. Unlike the Lugosi, Lee, and Oldman versions of the vampire, this Dracula had a likeable side. Whether it was biting Cleon Jones’ cap, or throwing the ball from home plate over the center field fence, or bragging about ridiculously ancient relatives, Pedro Borbón knew how to have fun.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame