- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1972 Topps Bob Oliver

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Bob Oliver

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

With the Kansas City Royals newly entrenched as world champions, some 30 years after they last took the title, the timing is especially good to look at my favorite Royals card of all time. There have been a number of interesting Kansas City cards produced over the years, including the 1975 Topps card of Steve Busby (which mistakenly shows backup catcher Fran Healy instead of the young pitching ace), the 1978 card of George Brett (a very cool profile shot of the Hall of Famer sans a cap), the 1982 Fleer card of Dan Quisenberry (who can be seen in a middle of a crowded calisthenics workout), or the 1987 action-packed “Future Stars” card of Bo Jackson.

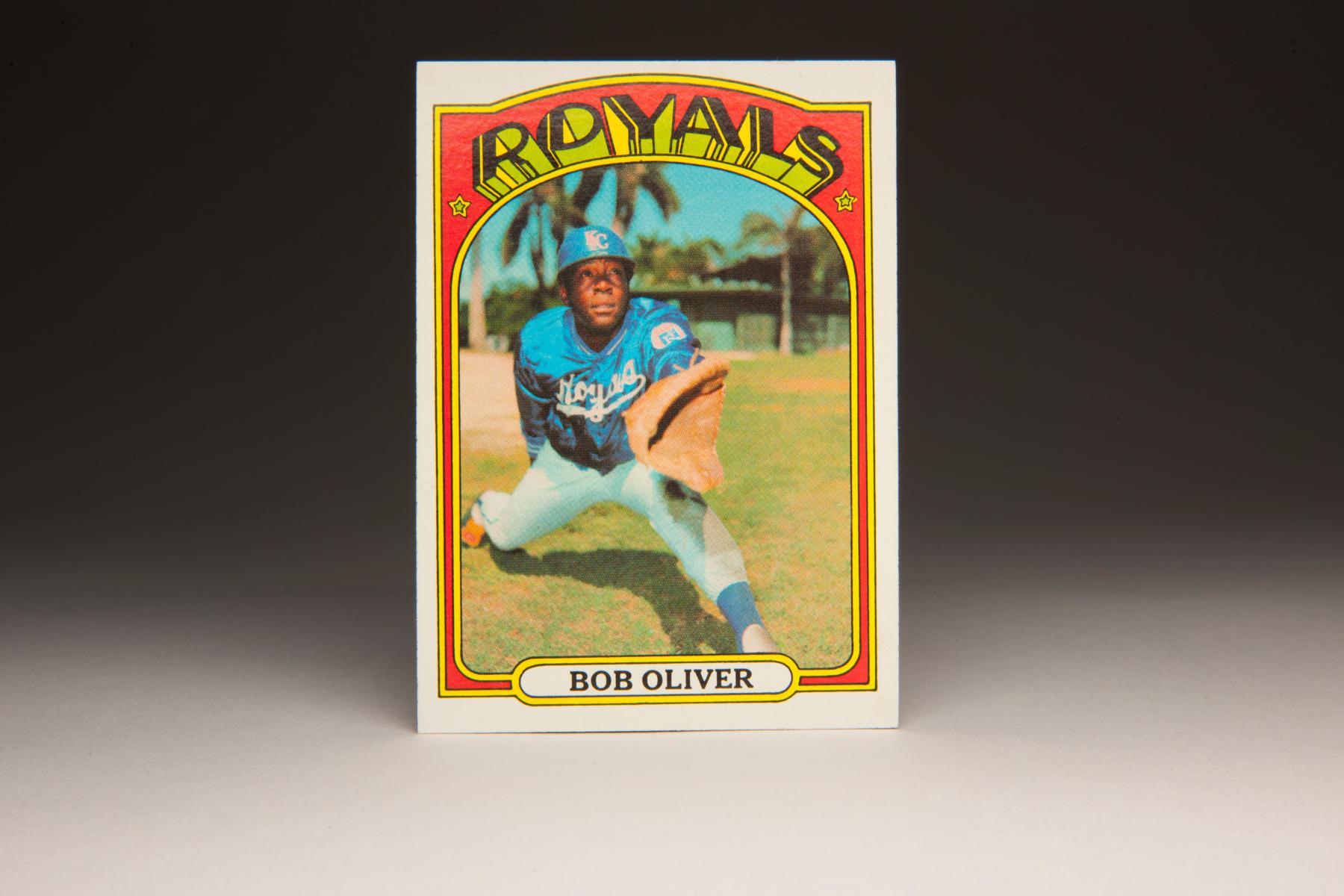

They are all excellent, and all worthy of a more in-depth profile. But my first choice remains the 1972 Topps card of Bob Oliver. First off, the 1972 set is still my favorite, in part because of the bright psychedelic colors that decorated the borders of the cards. Red is not one of the Royals’ primary colors, but this set makes you think that it is.

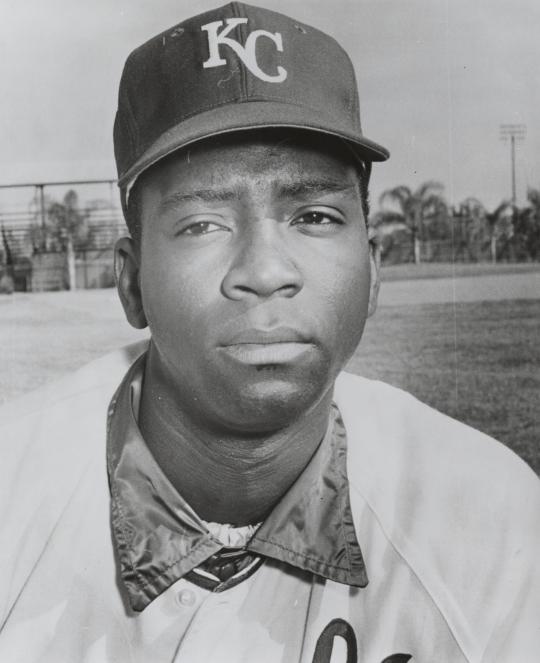

Then there is the actual photograph of Oliver, which saturates us in the style of the 1970s and the old school manner of Topps photography. We see Oliver wearing a bright satin windbreaker, as so many players did in Spring Training during that era. (This must have been considered a standard way to sweat off some excess poundage accrued during the winter months.) Oliver is also wearing a helmet while taking his fielding position, in a way that is reminiscent of two of his contemporary first basemen: Dick Allen and George “Boomer” Scott. And then we have the overly exaggerated pose, with Oliver stretching his front leg far for an imaginary throw, as if he were playing in an actual game. This kind of photograph typifies the over-the-top postures that Topps once preferred.

Just to add to the fun, the angle of the Topps camera creates the illusion of a first baseman’s mitt that is significantly larger than what the rules would allow. Oliver’s mitt appears so oversized that it could be used to cook up a pancake; it might have had the length and width of your standard kitchen frying pan.

As a final touch, Topps provides us with the backdrop of Spring Training, where so many of their photographs were shot in the early seventies. The presence of bright blue skies and palm trees, not to mention what appears to be some kind of storage shed deep in the background, tell us clearly that this is a Spring Training practice field, far removed from the rigors of the regular season at Royals Stadium. When you’re collecting baseball cards during the last vestiges of winter in February and March, there is nothing better than seeing cards that have been photographed in the warmth of Florida.

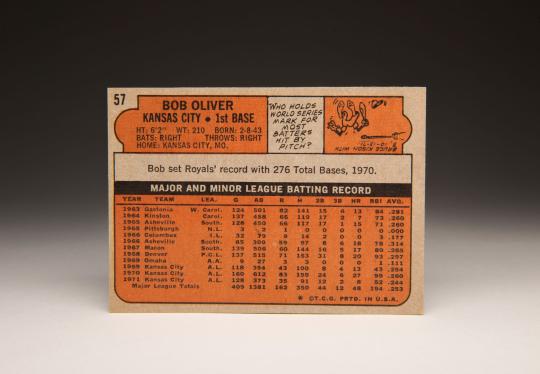

Now that I’ve established my admiration for this card, it’s time to tackle the subject of the card itself; he is also quite fascinating. It’s not particularly well known, but Bob Oliver is part of a two-generation baseball family that stretches from the 1960s nearly to the current day. He’s also one of the few major league players to also serve as a police officer.

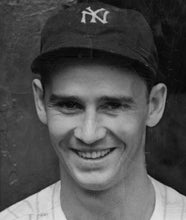

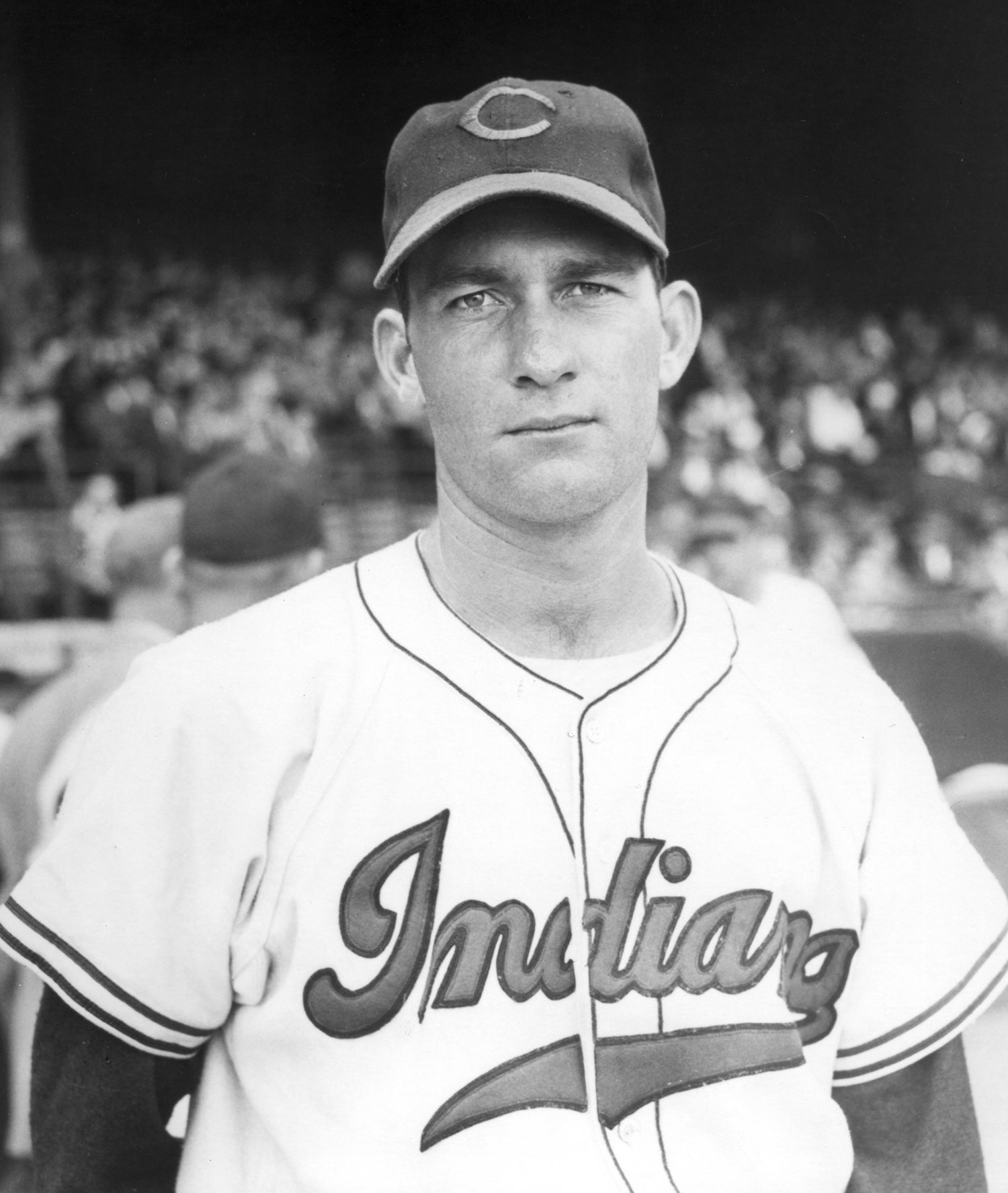

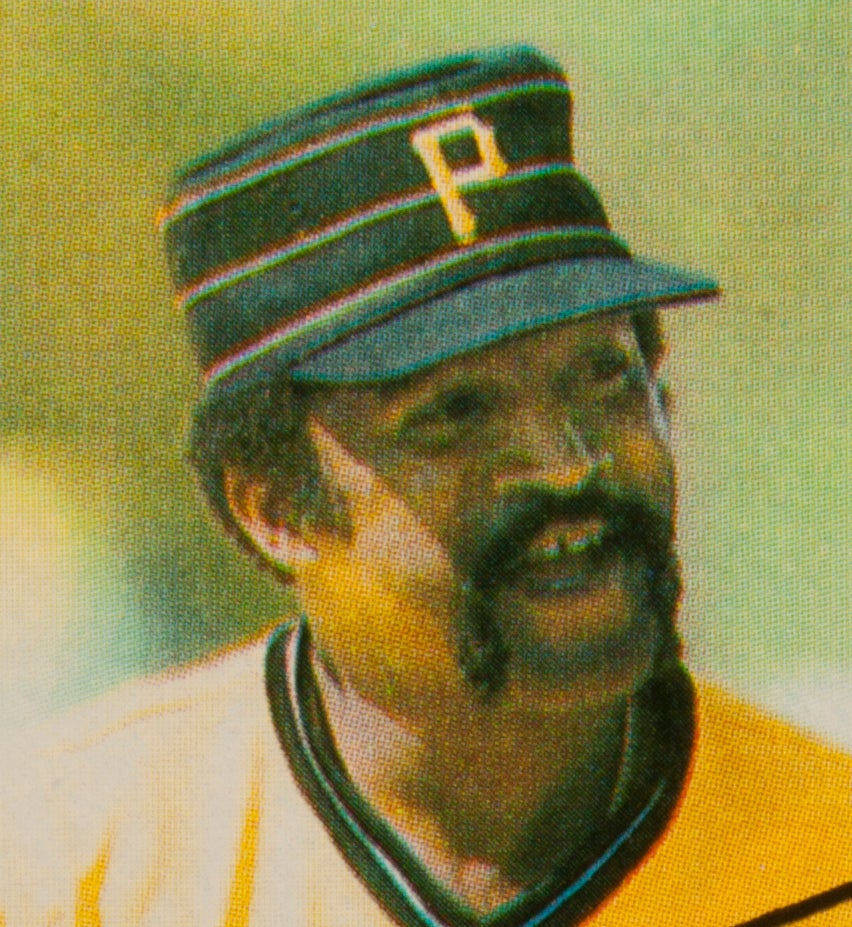

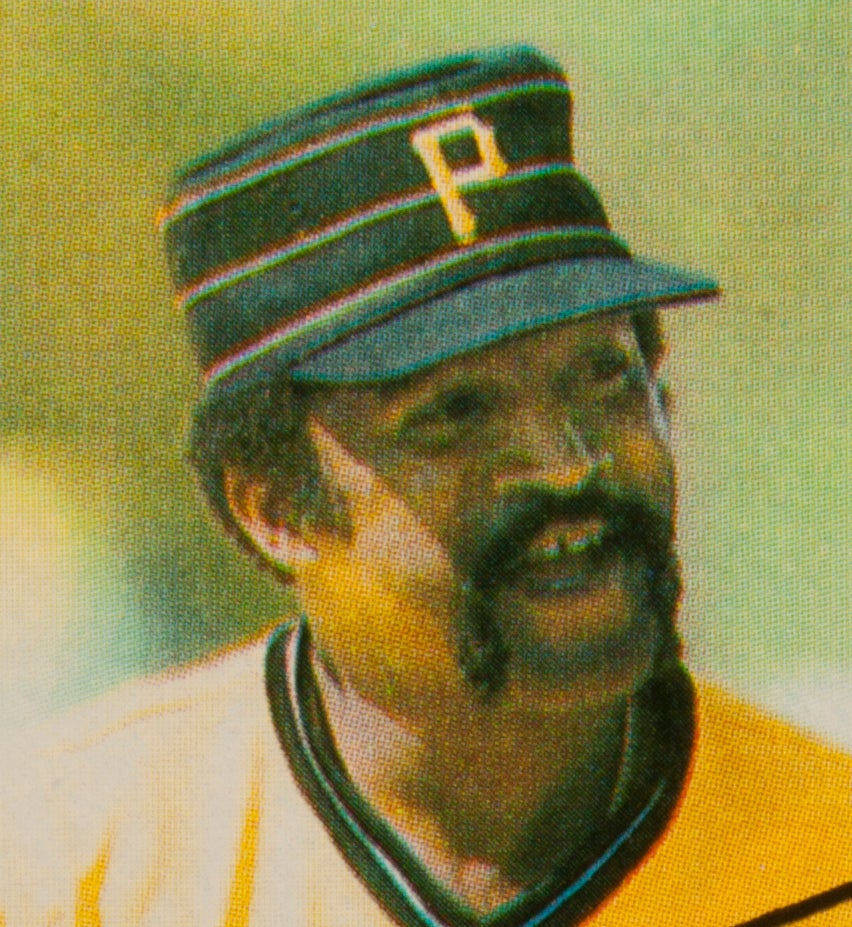

Oliver’s career started with the Pittsburgh Pirates, who signed him as an amateur free agent in 1963. He then made his big league debut only two years later, but it was rather brief. Called up in September, he played in only three games, going hitless in two at-bats. That was the extent of his Pirates career. He went back to the minor leagues for the next two seasons, largely because he was blocked at the four different positions that he could play: by Willie Stargell in left field, Donn Clendenon at first base, Maury Wills at third base, and a fellow named Roberto Clemente in right field. With nowhere to go, the Pirates felt it best to trade Oliver for pitching. After the 1967 season, they sent him to the Minnesota Twins for journeyman right-hander Ron Kline.

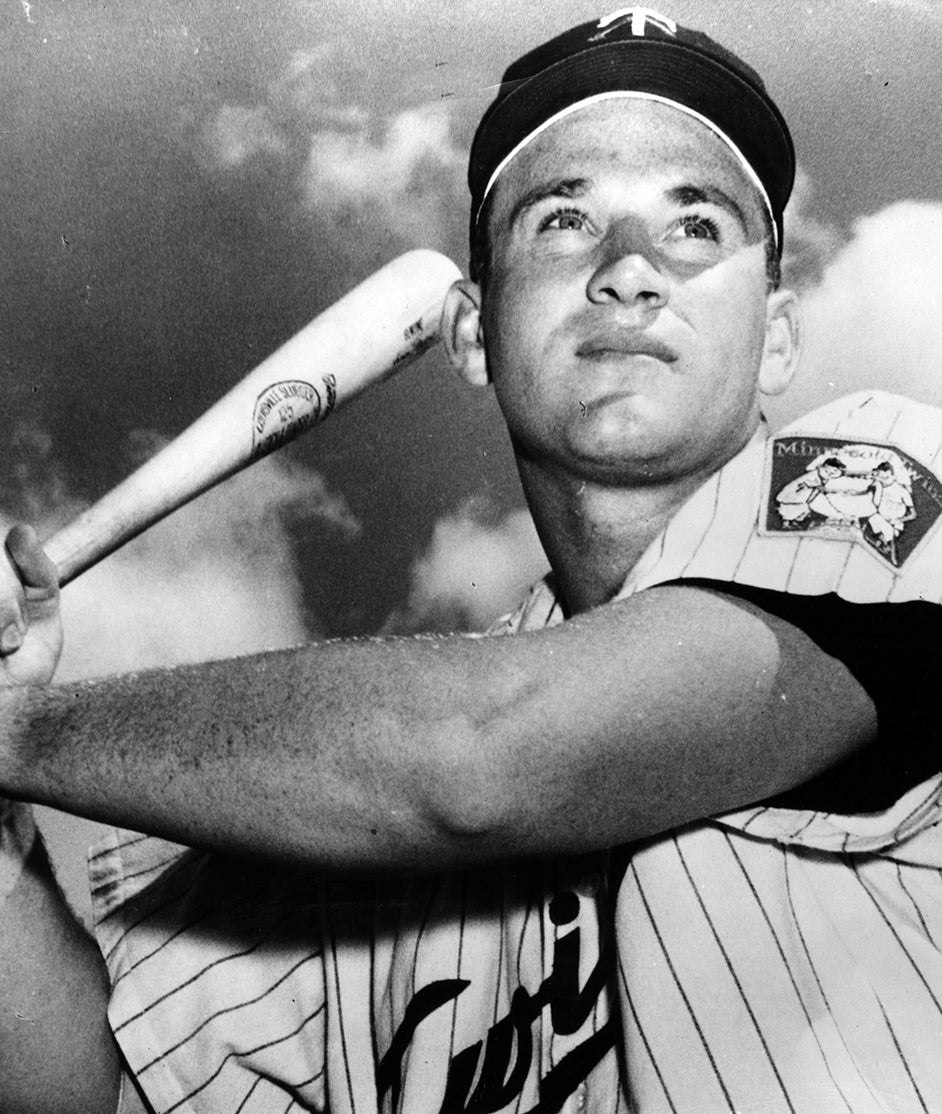

It’s not clear why the Twins felt Oliver would be able to make a breakthrough in Minnesota either. After all, the Twins already had Harmon Killebrew at first base, Cesar Tovar at third, and Bob Allison and Tony Oliva in the outfield corners. Where, oh where to play? Once again, Oliver found himself buried in the farm system.

Thankfully, a break came in the form of expansion. With four new teams set to join the major leagues in 1969, they all needed talent in the worst way. The Royals, one of the new entrants in the American League, selected Oliver with the 19th pick in the expansion draft. They loved his power, his athleticism, and his versatility, and considered themselves fortunate to draft a young talent who was still only 25 years old.

The Royals, managed by Hall of Famer Joe Gordon, made Oliver their Opening Day right fielder. Batting sixth, Oliver went 1-for-5 in the Royals’ inaugural game, as Kansas City squeezed out a 4-3 victory in 12 innings against Oliver’s former organization, the Twins.

Oliver played semi-regularly with the expansion Royals of 1969; he played the outfield corners, center field, first base, and third base. He actually played more in center field than he did anywhere else, which was surprising given that he had virtually no experience at the position. At times, the Royals featured an outfield of Oliver in center, Lou Piniella in left, and Ed “Spanky” Kirkpatrick. That might just have been one of the most defensively challenged outfields of all time, but it should not have been too surprising a development for an expansion team.

At the plate, Oliver flashed some promise. He also made some Royals history. He became the first Royal to collect six hits in a nine-inning game and the first player in franchise history to blast a grand slam. For the season, he hit 13 home runs 118 games, but he batted only .254 and drew a mere 21 walks. The following season, the breakthrough came. Playing for two new managers in Charlie Metro and Bob Lemon, who made life easier for him by using him only at first base and third base, Oliver hit 27 home runs and drove in 99. Oliver also received some support in the American League MVP vote, even if the Royals were still years away from contention.

Oliver became the Royals’ top home run hitter, which only made it more frustrating when his power output fell to eight home runs in 1971. That winter, the Royals acquired John Mayberry to play first base, mandating a position switch for Oliver. He moved to right field, appearing there in 16 games to start the 1972 season. But Oliver wasn’t best suited to play right field anymore; additionally, the Royals needed pitching. So in May, just a few months after his Topps card came out, the Royals traded Oliver to the California Angels for right-handed pitcher Tom Murphy.

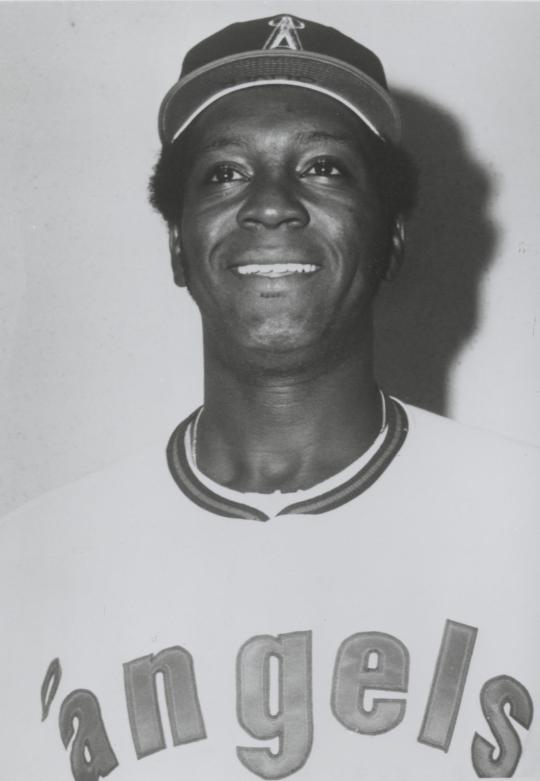

The trade turned out to be a tonic for Oliver. He could now play first base, by far his best position, while concentrating on the art of hitting. He hit 19 home runs and batted .269 for the Angels that summer, while also playing a smooth first base. Off the field, Oliver developed good relationships with his teammates and the California media. The local writers dubbed the mild-mannered and easygoing Oliver “King Ollie.”

While with the Angels, Oliver began pursuing a second career during the offseason. He became a police officer with the Santa Ana Police Department, specializing in truancy involving local students in Santa Ana. “We find out which kids aren’t in school, then find out why they aren’t there,” said Oliver. “Most of them have family problems. Their folks aren’t there.”

Oliver also worked the streets, dealing with motorists and other citizens. “I’m a street cop,” Oliver said without hesitation. “I’m concerned with whatever happens to the guy in the street.” One of those concerns involved drug abuse. “You can’t imagine how heartbreaking it is,” Oliver told the Sporting News, “when you have to tell a 13-year-old drug user, ‘Kid, you’ll have to come downtown with me.’ ”

In the meantime, Oliver continued to thrive on the field with the Angels. In 1973, he hit 18 home runs while playing three different positions and also serving as a DH. Then came the difficulties of the 1974 season. Oliver showed up to spring training overweight. At nearly 235 pounds, Oliver was too big for his six-foot, three inch frame. As the season progressed, he did his best to lose weight, dropping 30 pounds along the way. But his power also suffered. He hit only eight home runs in 110 games as the Angels fell out of contention in the American League West. In early September, the Angels sold Oliver’s contract to the Baltimore Orioles, who were vying for the AL East title.

The O’s ended up winning the East, but because Oliver had joined them after the Sept. 1 deadline, he was deemed ineligible for the playoffs and World Series. That was particularly frustrating for Oliver, who never made the postseason during his career.

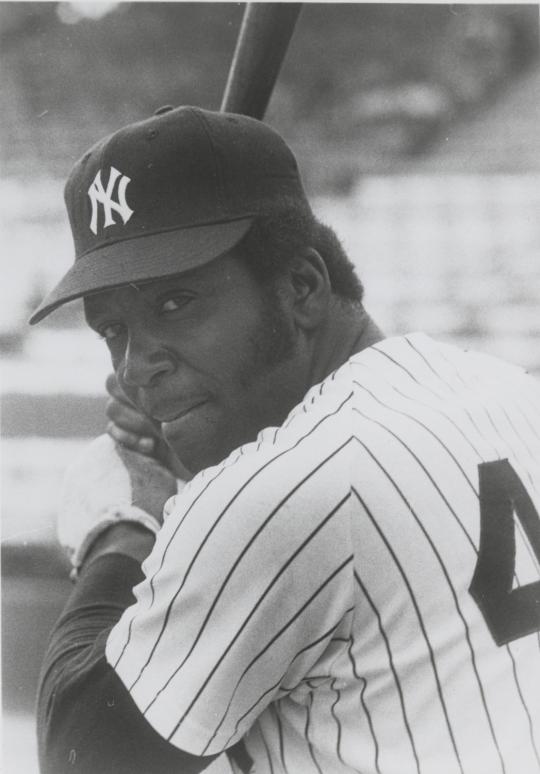

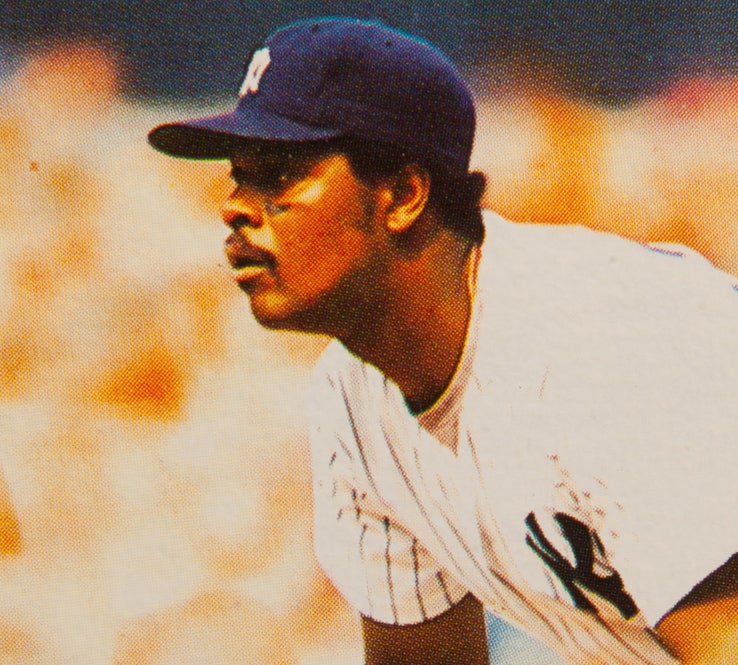

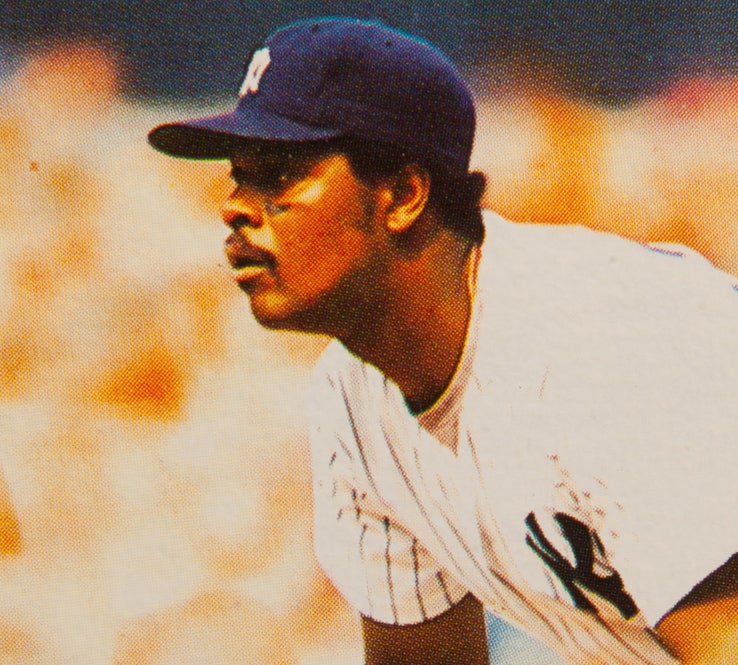

After the 1974 season, the Orioles sold Oliver to the New York Yankees, who always seemed to be in a constant search for right-handed hitting to balance their lefty-leaning lineup. They hoped that Oliver could fill the bill, but he batted only .132 with no home runs in 18 games. At 32, the Yankees believed that Oliver was done, so they gave him his unconditional release.

Over the next three seasons, Oliver spent time in the farm systems of the Philadelphia Phillies, the Pittsburgh Pirates, and the Chicago White Sox, all as part of an effort to return to the major leagues. But no one would offer him a major league deal. So Oliver sought refuge in the Mexican League, closing out his career with the Puebla and Veracruz franchises in 1978 and ’79.

Oliver had done his best to prolong his playing career. He would never again work for a major league team, but he maintained a connection to the game in a far more important way. In 1993, 23-year-old Darren Oliver would make his debut for the Texas Rangers. Darren is Bob Oliver’s son, born in 1970. From 1993 to 2013, Darren continued the family legacy as a left-handed pitcher with a slew of major league teams. Between the two Olivers, they combined for 28 seasons of major league play.

The elder Oliver still remains involved in baseball through the Bob Oliver Baseball Academy, which is based in Sacramento and offers advanced instruction to youngsters ages 16 to 19. Even at 72 years old, Oliver remains active in running the academy and serving as an instructor. That’s not surprising, given how Oliver has always shown concern for youth, whether they’re missing school, tempted by drugs, or simply playing the game.

I wonder if any of those teenagers in the academy realize that Mr. Oliver once played for the Royals, the new world champions. If they do, they should offer him some congratulations. After all, he was a Royals original, back when the franchise started building to a championship conclusion.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

More Card Corner

#CardCorner: 1983 Topps John Mayberry

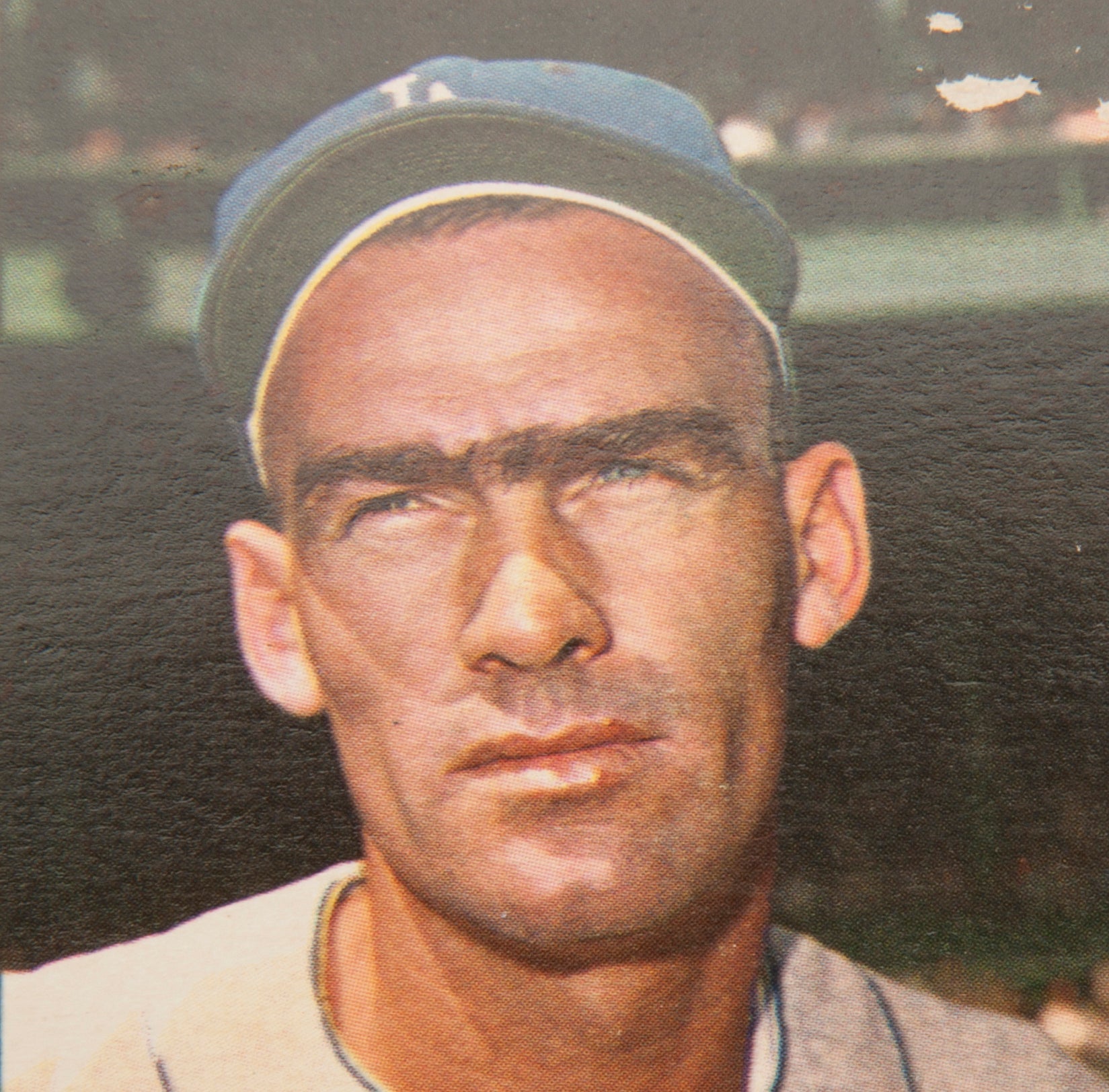

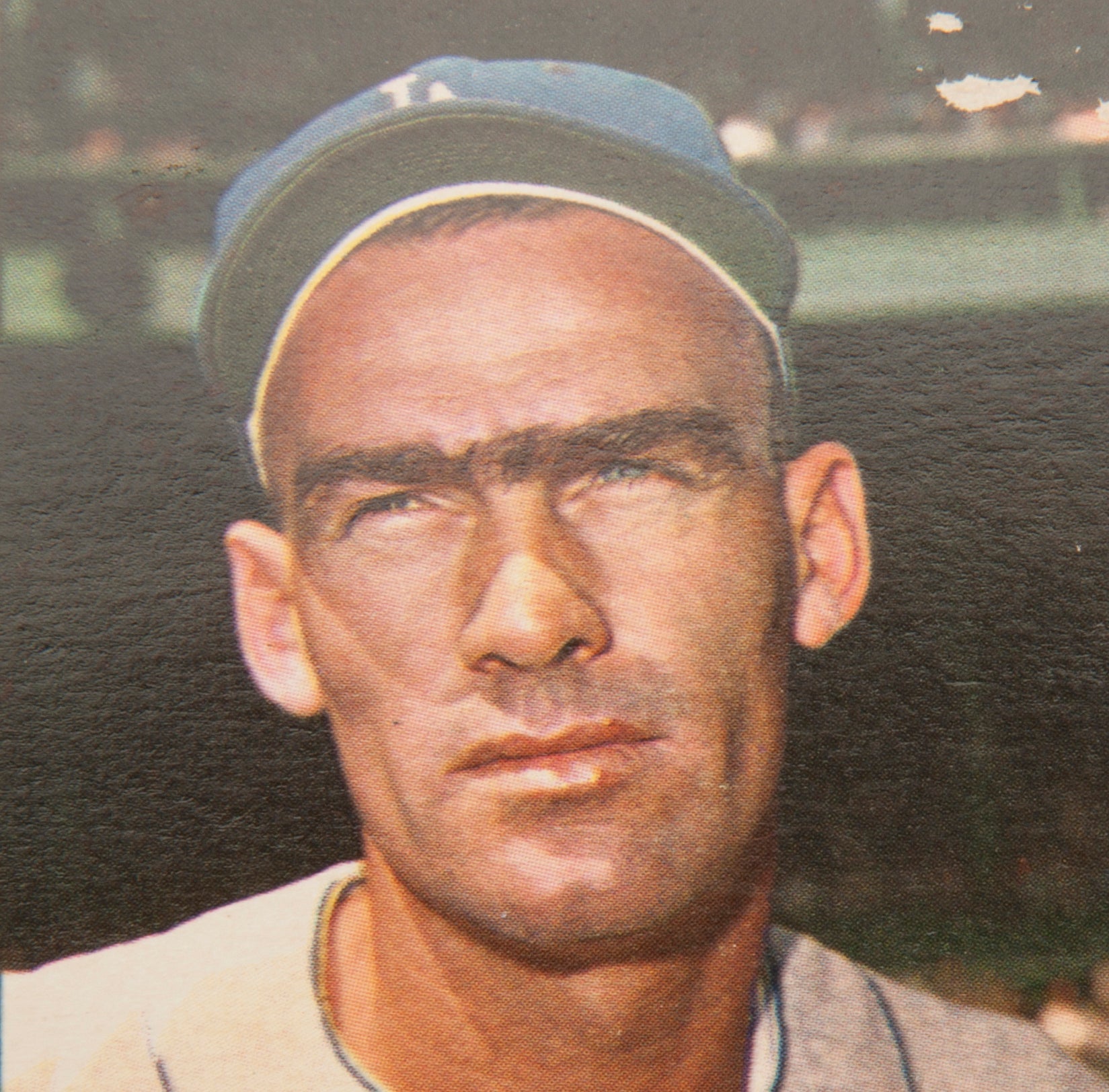

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Wally Moon

#CardCorner: 1982 Topps Luis Tiant

#CardCorner: 1983 Topps John Mayberry

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Wally Moon

#CardCorner: 1982 Topps Luis Tiant

Support the Hall of Fame

Related Stories

Davey Johnson’s managerial skills lead him to Cooperstown’s doorstep

1999 Hall of Fame Game

Hispanic Heritage Month

Eight on the Links

Chris von der Ahe - A Magnate for Success

Pre-Integration Era Committee Ballot to Be Considered Dec. 7 at Baseball’s Winter Meetings

Writers Elect Four to the Hall for the First Time in 60 Years

Hall of Fame Celebrates Baseball’s Love of Bubble Gum by Teaming Up with Big League Chew

Hall of Justice: David Justice visits Cooperstown

Baseball Luminaries Heading for Cooperstown for Hall of Fame Classic

01.01.2023