- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1976 Topps Oscar Gamble

#CardCorner: 1976 Topps Oscar Gamble

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

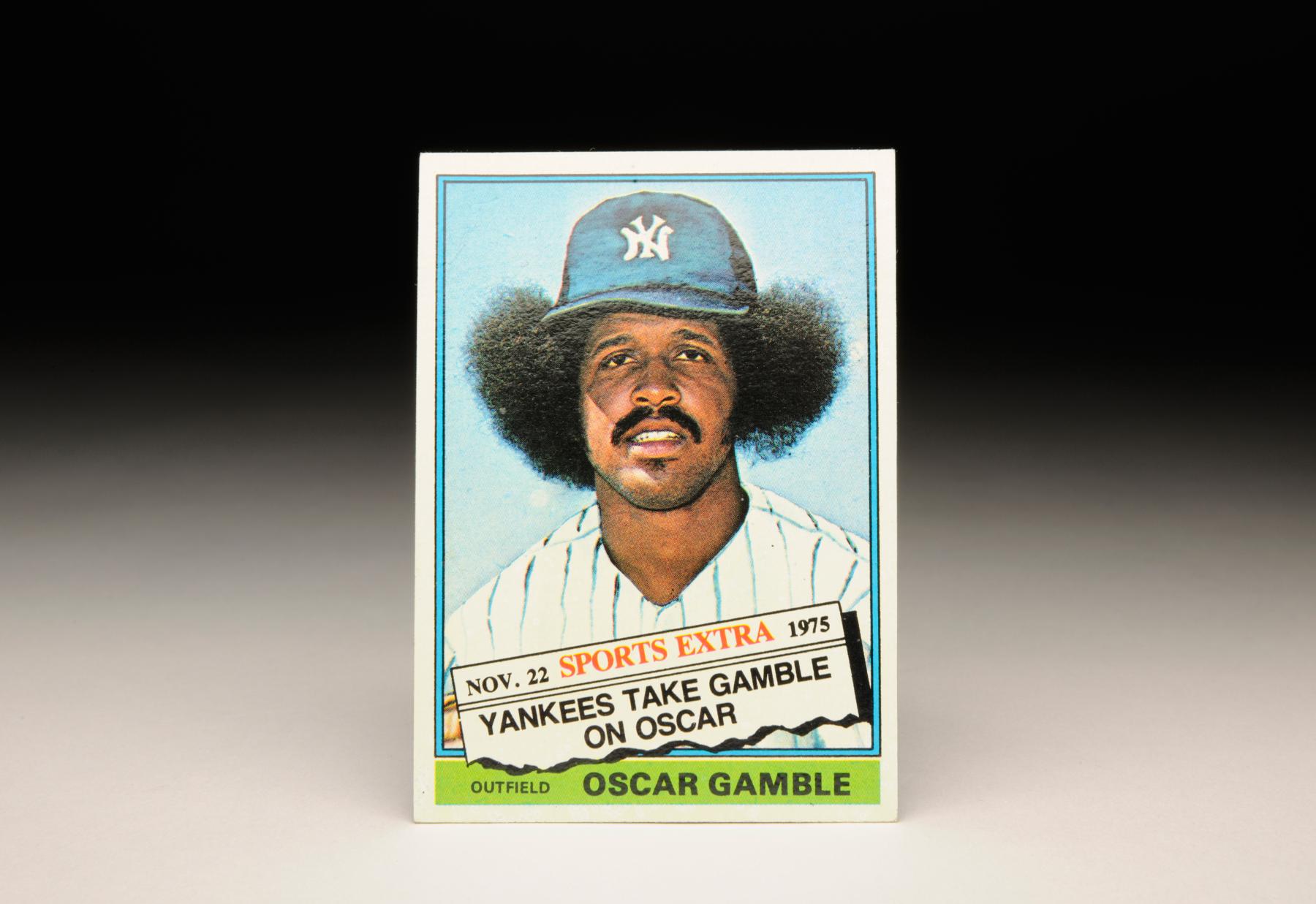

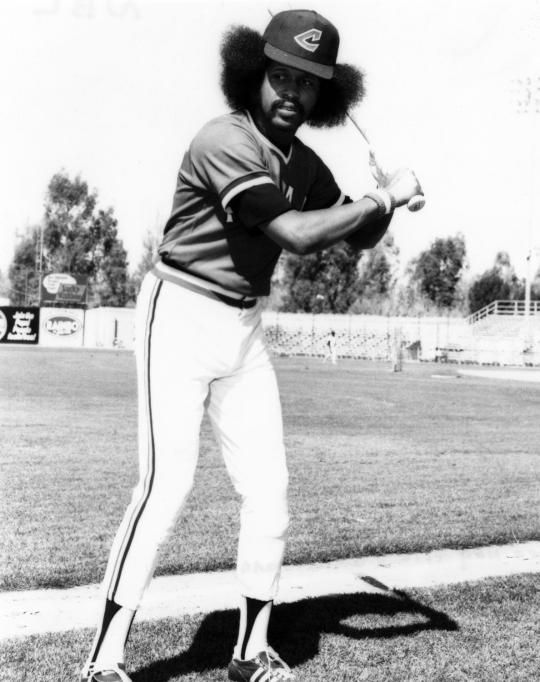

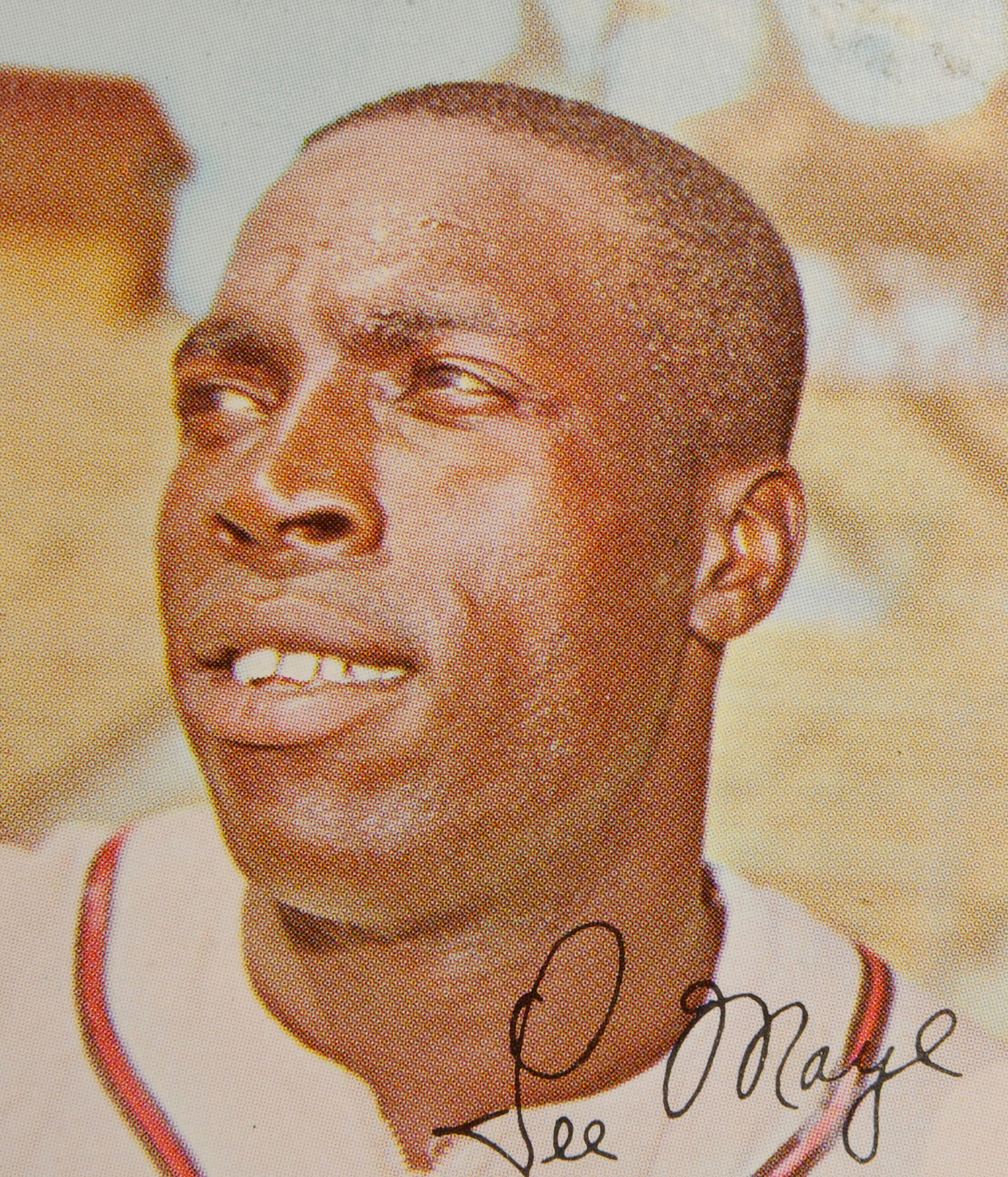

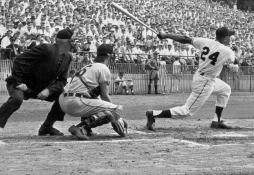

Hall of Fame visitors will surely pause at the Museum's newest exhibit, Whole New Ballgame, when they see this baseball card. One of 72 new cards featured in the exhibit that chronicles baseball’s history from 1970 to the current day, Oscar Gamble’s 1976 Topps Traded card is like no other. It is the kind of card that forces you to stop, do a double take, perhaps even a triple take, and then shake your head in wonderment over the zaniness of the 1970s.

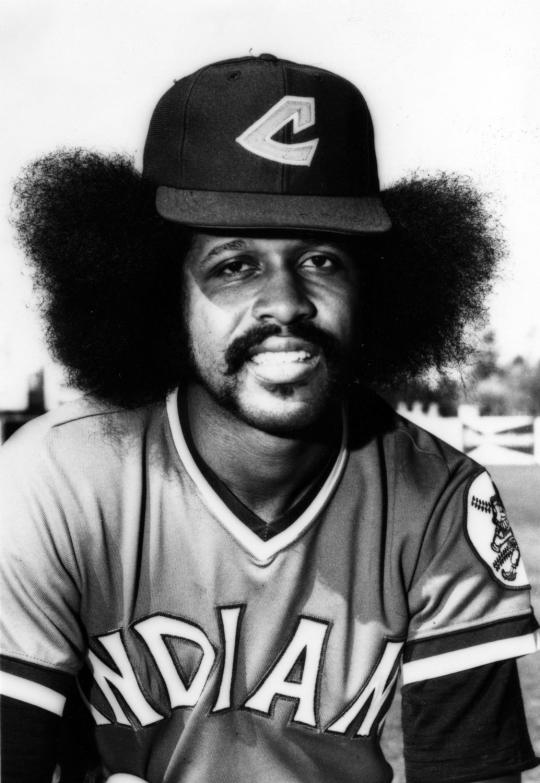

During his three seasons with the Cleveland Indians, Oscar Gamble’s large Afro—the biggest in baseball history, according to unofficial records—made for quite a sight at Municipal Stadium and other American League ballparks. Indians fans frequently serenaded Gamble with chants of “BO-ZO!” in tribute to the television clown who became so recognizable in the 1960s and 1970s while wearing a similarly large tuft of hair.

In this card, the cap is quite obviously airbrushed, with the colors of the New York Yankees drawn over the design and logo of the Indians. But it’s the hair that always draws the attention on the Gamble card. In reality, his oversized hair created a small fashion concern. By the end of each game, Gamble was usually left with a particularly bad case of “hat hair,” with his Afro suffering severe indentations from both his cap and his helmet.

More importantly, Gamble could rarely complete a turn around the bases without his helmet falling to the ground. Similarly, long chases after fly balls in the outfield would result in the unintended departure of his cap from his head. Caps and helmets simply didn’t fit over his Afro, one that rivaled the hairstyles seen in the American Basketball Association during the mid-1970s. (For those who remember Darnell “Dr. Dunk” Hillman, Gamble’s Afro was nearly as massive and majestic as the one grown by the former ABA power forward.) The “problem” reached such extremes in 1975 that Gamble held a contest in which he asked Indians fans for recommendations on how to wear his hats. “We’re open to all suggestions, except a haircut,” Gamble slyly informed Cleveland sportswriter Bob Sudyk.

As much notoriety as Gamble accrued for his iconic “head piece,” he acquired a lasting reputation for additional reasons during an eventful career in the major leagues. Gamble signed with the Chicago Cubs in 1968, thanks largely to the scouting efforts of Buck O’Neil. It was O’Neil, the former first baseman and managerial standout from the Negro Leagues, who noted Gamble’s talents. Even though Gamble wasn’t selected until the 16th round of the draft, O’Neil called him the best prospect he had signed since Ernie Banks. Shortly after Gamble arrived at Spring Training in 1969, Cubs manager Leo Durocher gloated about the talents of his 19-year-old outfielder, comparing him to a legendary outfielder whom he had managed years earlier.

“Gamble could be another Willie Mays. I know it sounds wild, but this kid compares with Willie when Willie was first coming up,” Durocher told theSporting News. “Remember, I managed Mays, too, as a kid. Gamble can run, throw, catch a ball, and he swings a quick bat…. He can sting the ball.”

The Cubs called up Gamble later that summer, hoping that he could fill a vacancy in center field, but he struggled with making breaks on fly balls and throwing to the right base. Those defensive problems may have contributed to his departure. That winter, the Cubs traded Gamble and reliever Dick Selma to the Philadelphia Phillies for Johnny Callison.

Gamble would spend the next three seasons in Philadelphia, but continued to struggle, both as a center fielder and as a hitter. Clearly, he was miscast in center field, but he didn’t appear to have enough of a bat to carry him in either left field or right field, either. So at the 1972 winter meetings, the Phillies gave up on Gamble, sending him and minor league home run king Roger Freed to Cleveland for outfielder Del Unser.

The trade turned out to be a godsend. Thanks to a more open and more crouched batting stance, Gamble finally began to hit with power. Wisely, the Indians moved him from center field to the outfield corners. Off the field, he also showcased more of his colorful personality. Recognized as the flashiest dresser on the Indians, Gamble once wore a pair of red, white, and blue plaid slacks, accentuated by red elevator shoes. Gamble was also one of the few major leaguers who could claim ownership of a disco. He would open up the establishment in 1976, turning over the day-to-day operations of the disco to his brothers.

While with Cleveland, Gamble also developed a reputation for a questionable attitude, at least in the minds of some. He chafed about a lack of playing time, sometimes complaining about being repeatedly benched against left-handed pitching. At least one critic considered Gamble disingenuous. “He talks about wanting to play,” an anonymous Indians player told the New York Daily News, “but when he gets the chance, he acts like he doesn’t want to play.”

For his part, Gamble regarded the criticism as off base and partly motivated by his appearance, perhaps resulting in an undertone of racism. “Yeah, people always ask me about my hair,” Gamble told the Sporting News in 1979. “I liked [the hair], but I guess it did cause me to get a bad reputation. People took one look at that hair and thought I was a bad guy. There were some sportswriters who wouldn’t even talk to me. They thought I was some kind of militant with my beard and my hair.”

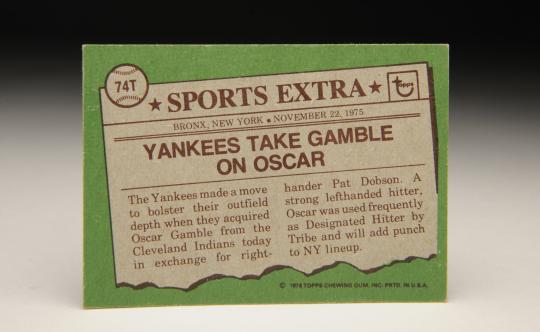

In actuality, Gamble was anything but militant. He was fun loving, outgoing and accessible. Yet, the Indians still traded him, sending him to the Yankees for right-hander Pat Dobson during the spring of 1976. (That’s why Topps included Gamble as part of its traded set.) The Yankees loved Gamble’s left-handed swing and his ability to crush right-handed pitching, but they didn’t care for his Afro. Unlike the Indians, the Yankees didn’t permit large Afros, long hair, beards, or anything less than conservative grooming.

Shortly after the trade, Yankee owner George Steinbrenner instructed public relations director Marty Appel to arrange an immediate haircut for Gamble. Appel faced one difficulty: Gamble had arrived on a Sunday, a day when all barbers in Florida were off. Using his contacts, Appel found a barber and made special arrangements for a “private” cutting. One can only imagine the volume of hair that ended up on the cutting room floor! It cost more than $30 to trim eight inches from Gamble’s Afro, a barbershop fee that was nearly unheard of at 1970s prices. Perhaps more importantly, Gamble’s wife cried when she saw that his large Afro was gone.

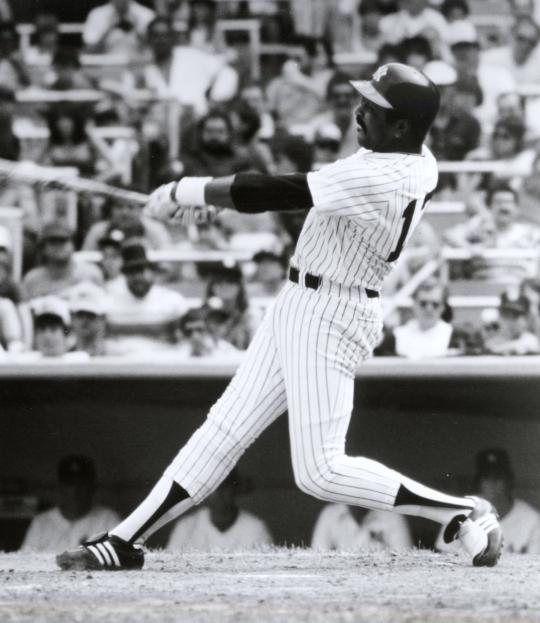

Gamble himself was ready for a change, which made it much easier to wash and dry his hair after games. He also found an ally in New York, coming in the form of the Big Apple media machine. He became one of the most quotable Yankees, often hamming up his responses in a larger-than-life manner. On the field, Gamble provided the Yankees with an expected level of power; he hit 17 home runs in 340 at-bats, while using his patented deep-crouch batting stance in which he actually seemed to face the right field stands at Yankee Stadium.

On the flip side, his batting average and on-base percentage fell short of Yankee desires. During the winter, the Yankees signed Reggie Jackson as a free agent. That made Gamble available—and expendable. With a need for a new shortstop, the Yankees sent Gamble to the Chicago White Sox for Bucky Dent during the spring of 1977.

With the Sox, Gamble became part of the “South Side Hit Men,” who featured a number of big hitters, including Jorge Orta, Eric Soderholm, Ralph Garr, Chet Lemon, and Richie Zisk. But White Sox owner Bill Veeck did not have the resources to sign Gamble to a long-term contract, forcing him to let the left-handed slugger enter the brave new world of free agency. Gamble signed a huge multi-year contract with the San Diego Padres, but hit so poorly for his new team that he lasted only one season in Southern California. That winter, the Padres traded Gamble, sending him to the Texas Rangers for the trio of first baseman Mike Hargrove, utility man Kurt Bevacqua, and catcher Bill Fahey.

After his whirlwind tour of both leagues, Oscar rejoined the Yankees for a second stint in 1979. It was late in a lost season for the Yankees, who were looking to rebuild for 1980. So the Yankees traded center fielder Mickey Rivers to the Rangers for Gamble and several minor league players to be named later. Upon his return to New York, Gamble reminded writers of his way with words. “I’m a man of character, a man of stature, a man of ability,” Gamble kiddingly informed The New York Times. Gamble also liked to give himself nicknames. He called himself “The Big O.” During his tenure with the Yankees, Gamble also began referring to himself as the “Ratio Man” because of his tendency to hit lots of home runs in small numbers of at-bats. Some of his Yankee teammates joined in the refrain.

The highlight of Gamble’s second Yankee tenure came in the 1981 Divisional Series, when he batted .600 with two home runs against the Milwaukee Brewers. No longer questioned about his attitude, Gamble became especially well-liked by fans and teammates during his second stint in the Bronx. He maintained that popularity until the spring of 1982, when he vetoed a trade that would have sent him, first baseman Bob “The Bull” Watson, and pitcher Mike Morgan to the Rangers for Al Oliver. Invoking his partial no-trade clause, Gamble wanted no part of going back to Texas, an organization that had traded him in 1979 without ever telling him directly. Still bitter about the Texas treatment, Gamble opted for the veto; it was a decision that infuriated Steinbrenner, who wanted Oliver badly. “The Boss” carried a grudge; some writers claimed that he ordered manager Billy Martin to limit Gamble’s playing time as a form of punishment.

In spite of the challenges, Gamble retained his ever-present smile and remained a popular part of the Yankees through the 1984 season. In October, the Yankees released him. He opted to return to the White Sox, but he was just a shell of the player that Chicago had once witnessed. Now 35, Gamble batted only .204 with four home runs in 184 plate appearances. By mid-August, the White Sox decided to part ways, giving Gamble his unconditional release and ending his playing career.

Gamble has not worked in Organized Baseball since retiring, but has spent some time as an agent and became involved in the game at the youth level. His outgoing personality and sense of humor made him a good fit for such work.

He passed away on Jan. 31, 2018.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

More Card Corner

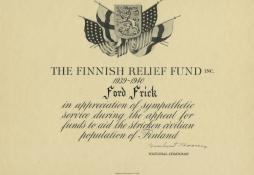

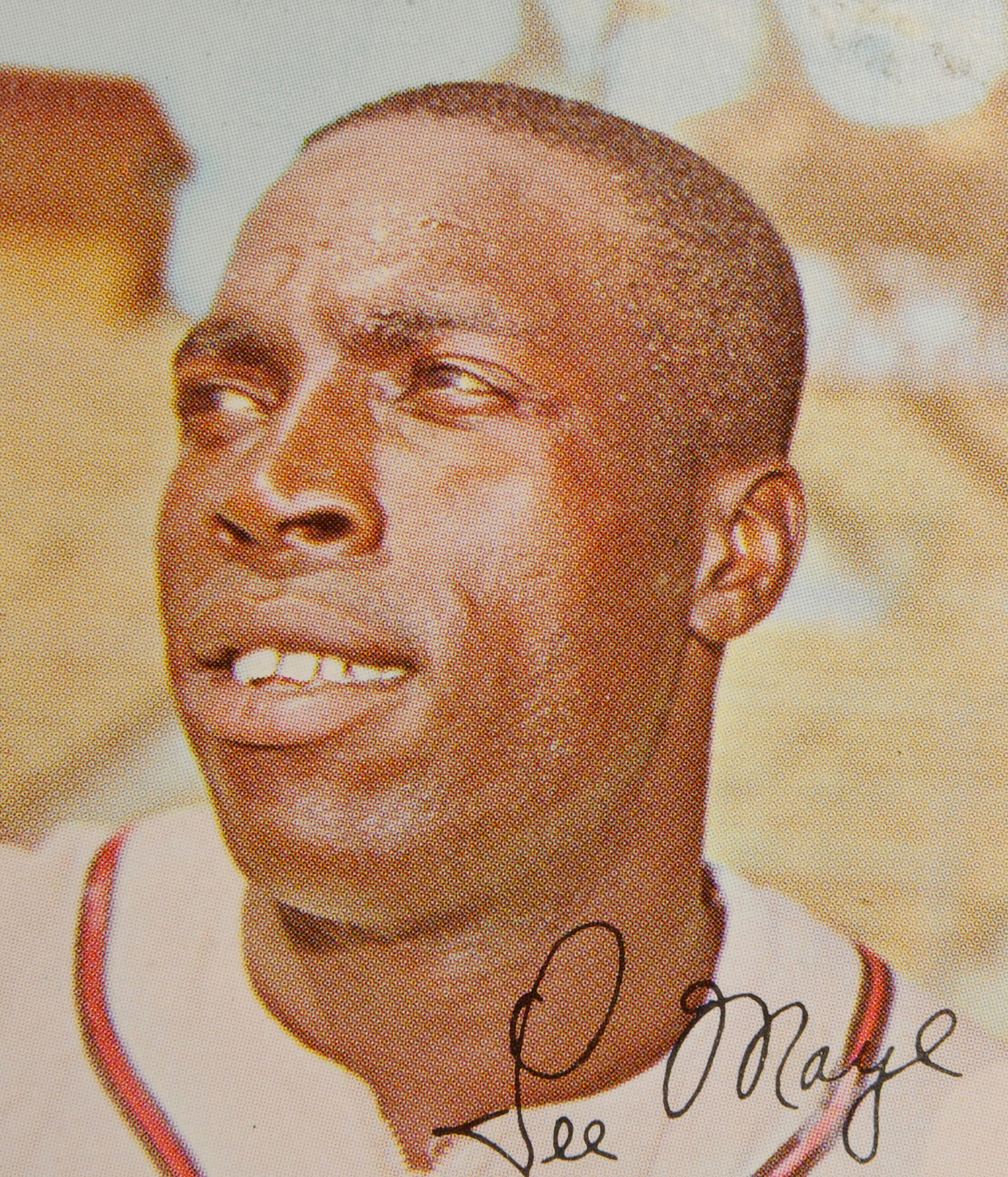

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Lee Maye

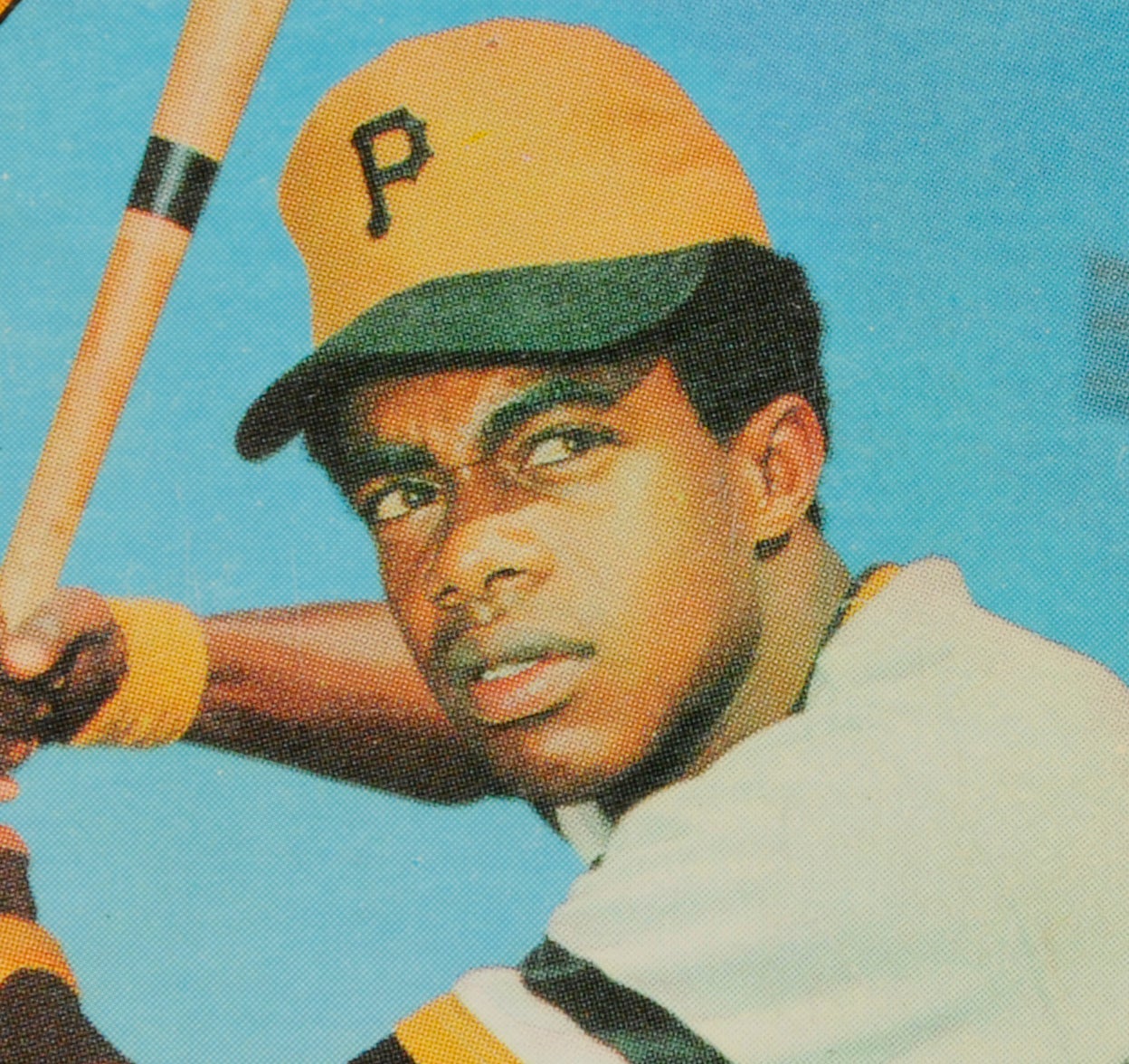

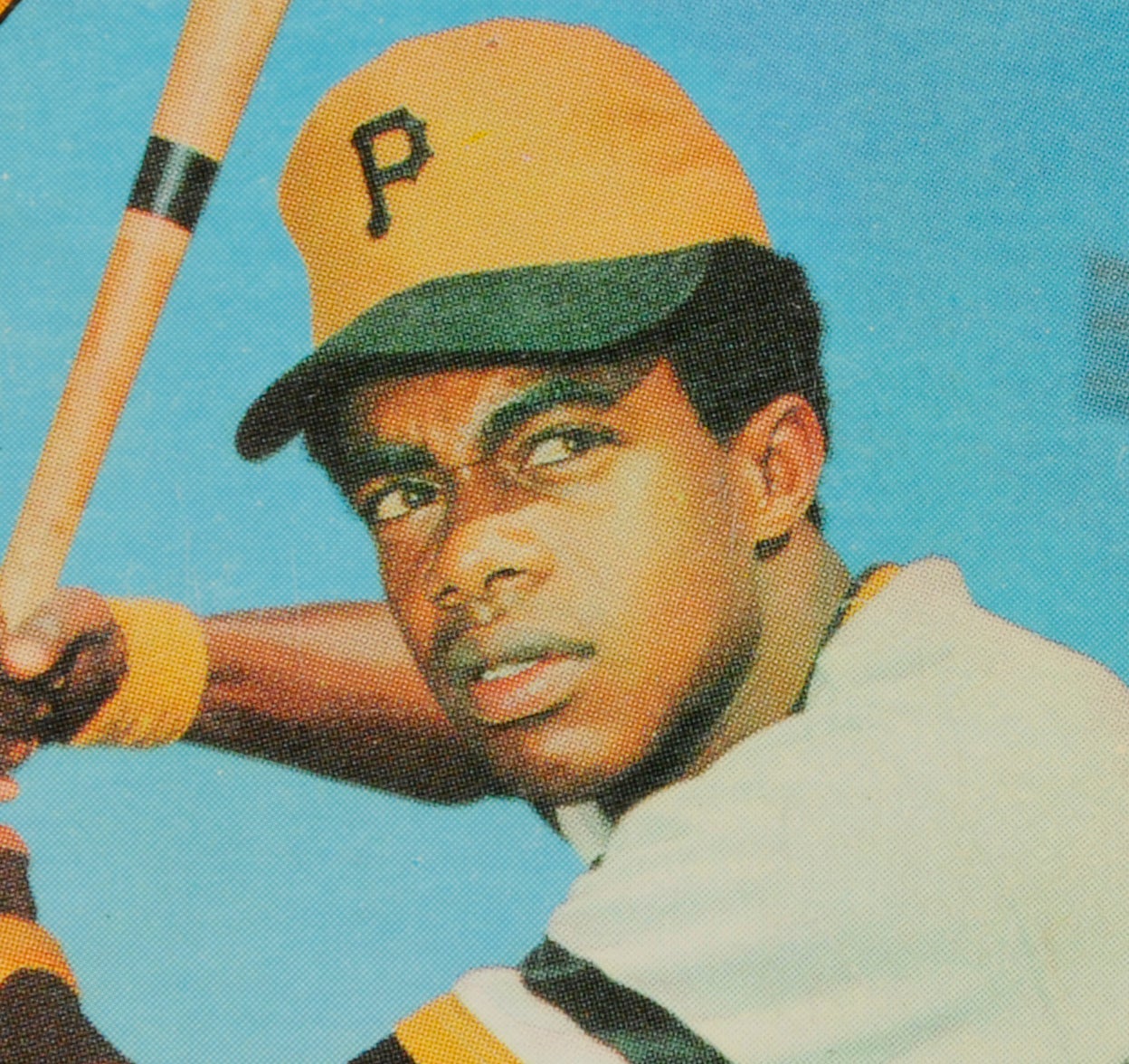

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Dave Cash

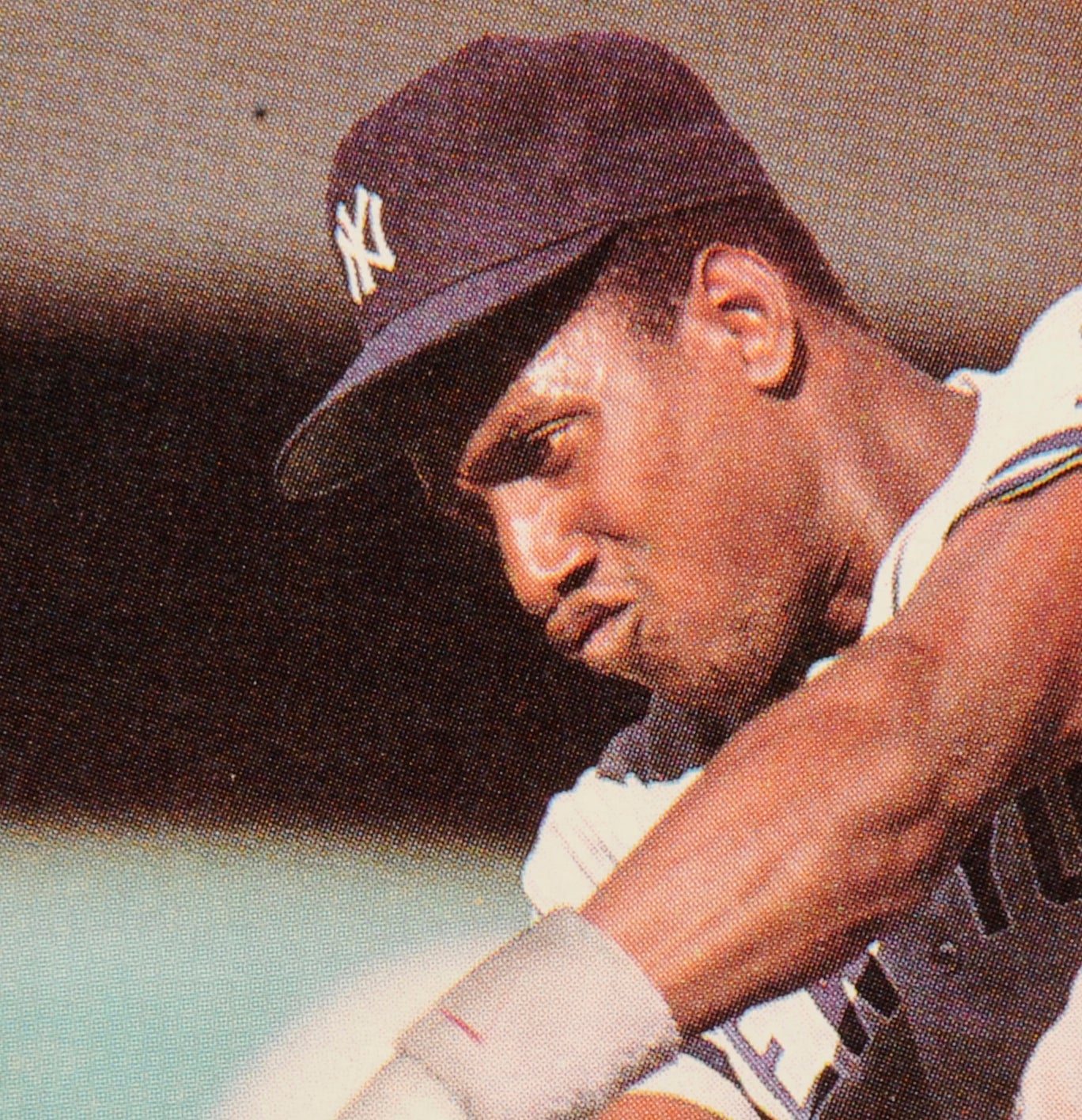

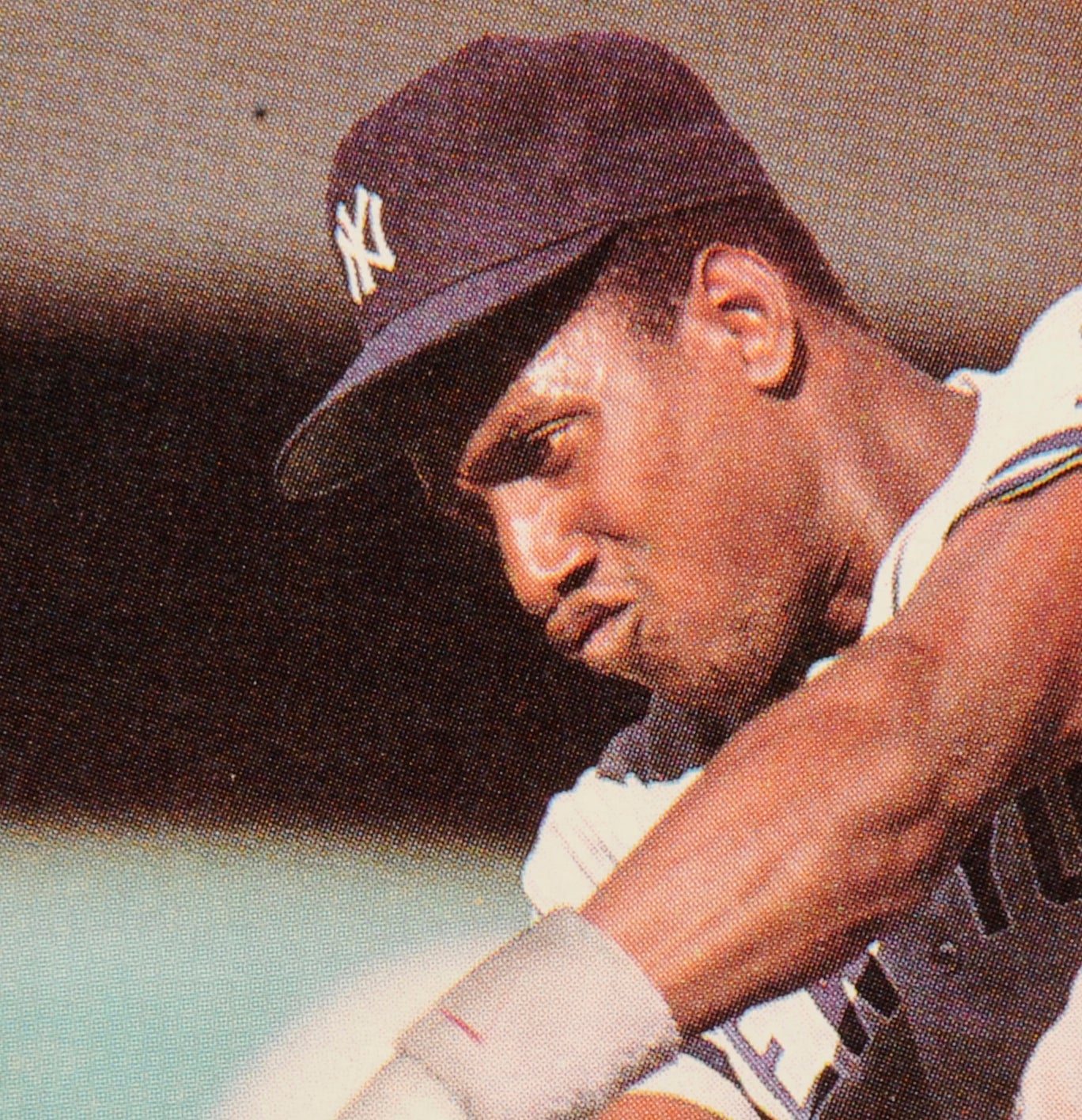

#CardCorner: 1991 Topps Roberto Kelly

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Lee Maye

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Dave Cash

#CardCorner: 1991 Topps Roberto Kelly

Support the Hall of Fame

Related Stories

Baseball-loving Librarians visit Museum

Two-Time MVP, Brewers Legend Robin Yount Joins Lineup for May 23 Hall of Fame Classic

Turn Two

#CardCorner: 1971 Topps Richie Scheinblum

#CardCorner: 1976 Topps Oscar Gamble

Watch the Stars on Main Street at Hall of Fame Parade of Legends Saturday, July 23

Irvin and Thompson debut for Giants

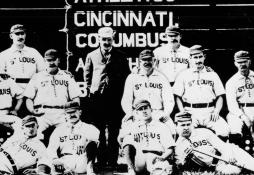

Chris von der Ahe - A Magnate for Success

1956 Hall of Fame Game