The secret of success in pitching lies in getting a job with the Yankees."

- Home

- Our Stories

- Eight on the Links

Eight on the Links

In 1921, baseball players from various teams converged in the resort town of Hot Springs, Ark., to soak in the therapeutic waters, “boil out the alcoholic microbes” and drop their off-season pounds in rubber suits before heading to their official spring training camps. When they weren’t in the spas, they would bowl, dance at the clubs, or, for those inclined, play a round of golf or two.

The players had arrived within several days of each other, and their activities were reported dutifully by veteran sportswriter William B. Hanna, on special assignment for the New York Herald. His daily dispatches included updates on the players’ exercise regimes, their respective weights, and rumors of their evening activities.

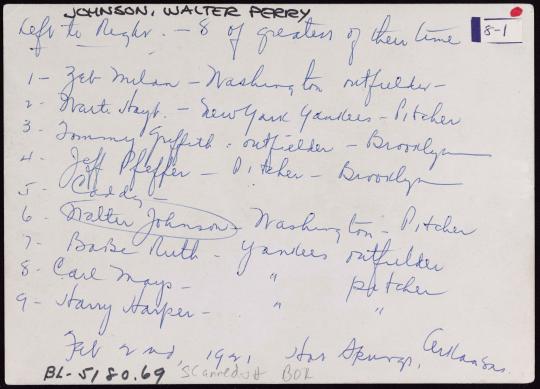

On Feb. 24, on a blustery morning, eight players from the Washington Senators, Brooklyn Dodgers, and New York Yankees posed for a photograph before a round of golf or, for those not golfing, a rigorous hike, “good work for the legs and possibly the liver,” reported the Herald. Recently digitized as part of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s Digital Archives Project, the photo is labelled on the front in a thick white print “HOT SPRINGS ARK 2, 24, 21.” The back, in a penciled script, lists the players, from left to right. Some are among the all-time greats, including Babe Ruth and Walter Johnson; others are mostly forgotten.

Standing left to right, Clyde Milan, Waite Hoyt, Tommy Griffith, Jeff Pfeffer, unidentified caddy, Walter Johnson, Babe Ruth, Carl Mays, and Harry Harper. The photograph was taken at Hot Springs, Ark. on February 24, 1921. BA-PF-Walter-Johnson-Misc-003 (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

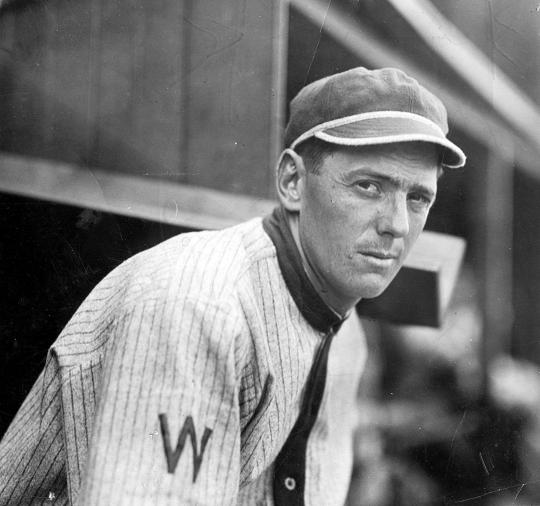

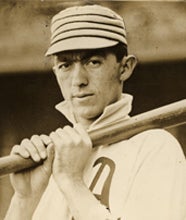

At the far left is Clyde Milan, an outfielder for the Washington Senators from Linden, Tenn. His hair flies wildly over his head, caught in a sudden gust of wind. He is among the hikers – identifiable by suitcoats and absence of clubs. Nicknamed “Zeb,” a word for people from small, rural towns, Milan was more interested in hunting and fishing than golfing. He’d go on hunting trips with his good friend and Senators teammate Johnson, who was also from a small town. Milan and Johnson were both the same age and had been signed by the Senators in the same year, and besides rooming together on the road, they shared a quiet, humble demeanor.

Milan had been known for his speed, breaking Ty Cobb’s single season base stealing record in 1912 with 88 (which Cobb would later reclaim), and stealing another 75 the next season. He finished his career with 495 steals, third-most at the time. But he was slowing down. Just shy of his 34th birthday, the upcoming season would prove to be his last as a full-time season as a player. In 1922, he’d be named player/manager for the Senators; coincidentally, while Johnson played under Milan in 1922, Milan would work under Johnson in 1929, when Johnson managed the Senators and hired Milan as a coach.

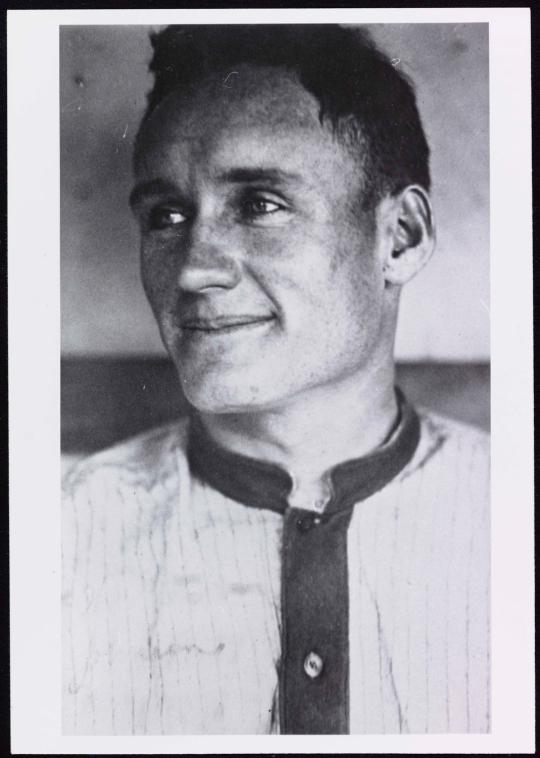

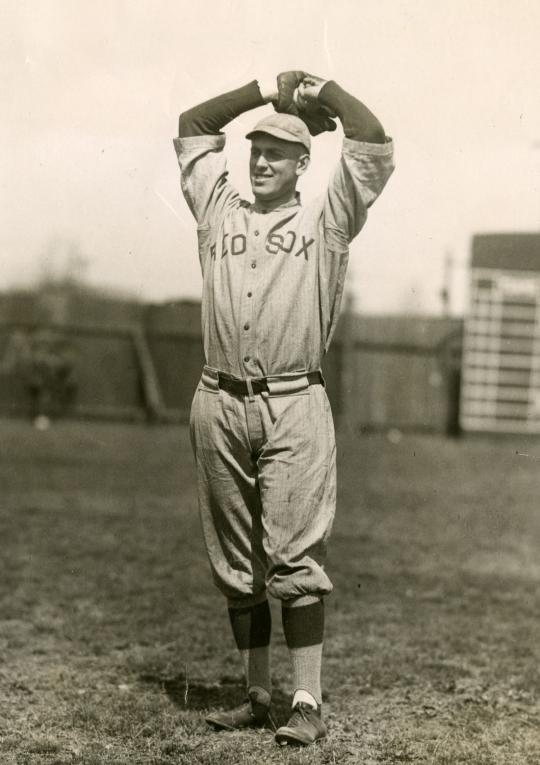

Standing next to Milan is Waite Hoyt, just 21 years old – the youngest in the group by five years and new to the Yankees, where he was reunited with former teammates Ruth and Carl Mays. It had been a difficult offseason for Hoyt, who had surgery on a double-hernia and found himself traded from the Red Sox. He showed up at Hot Springs with something to prove.

He has clearly come to golf, in a natty bow tie, a vest with a pocket watch, and golfing shoes. In a few days, the paper would report that Hoyt had taken to running to the ball after each stroke for better exercise, passing 7-8 groups in the process. His career, too, was about to race forward. That season, the baby-faced Hoyt would win 19 games and start a 10-year run with the Yankees in which he would go 157-98, the centerpiece of a 21-year, Hall of Fame career.

Third from left is Tommy Griffith, a veteran right-fielder for the Brooklyn Dodgers, who, at 31, was in the midst of a solid, if unspectacular, 13-year career. He was a great defender, with excellent closing speed on fly balls. He had only hit .260 with a .292 on-base percentage in 93 games the year before, but he would have a solid 1921 season, hitting .312 with a career-high in home runs. Shorter than the others and with a receding hairline, he could just as easily be mistaken for the corner drugstore owner as a baseball player, or a singer in a quartet, which, in fact, he was. He sang on the vaudeville circuit in the offseason. He had just arrived into Hot Springs, his suit a bit baggy on his frame. Griffith admitted he wanted to shed 15 pounds at Hot Springs, and the Herald had, perhaps uncharitably, called his cheeks “as fat as Ruth’s.”

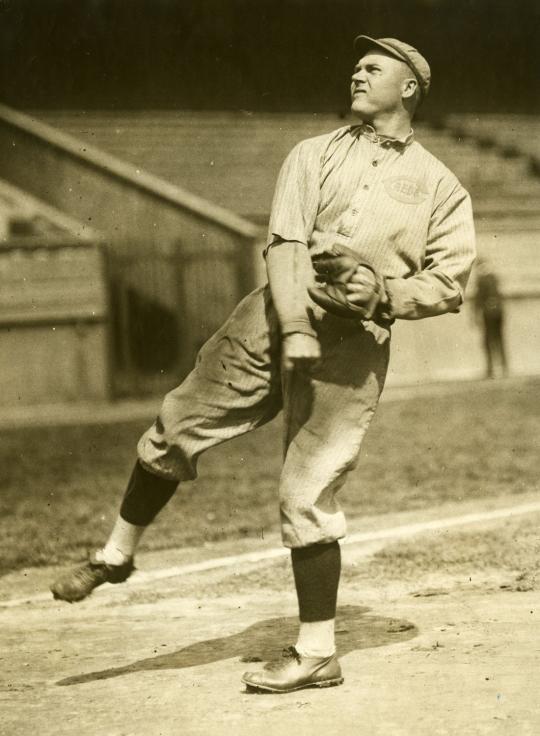

Towering above Griffith is Jeff Pfeffer, 6-foot- 3, Brooklyn pitcher and younger brother of big leaguer “Big Jeff” Pfeffer (whose name was not Jeff and who was “only” 6-foot-1). In 1914, Pfeffer had become the Brooklyn’s ace. From 1914 to 1920, Pfeffer had won 112 games against 74 losses, plus served a year in the Navy. He was an intimidating presence on the mound, unafraid to pitch inside, twice leading the National League in hit batsmen. But nearly 34, his skills were in decline. In the middle of the upcoming season, he would be traded to St. Louis. Quiet and mild off the mound, the lifelong bachelor stands here with his hands behind his back, his suit jacket formally buttoned, a pleasant smile on his face.

A young caddy, unidentified, stands between Pfeffer and Walter Johnson. He has the clubs ready to carry and is wearing a coat appropriate for the weather. Three days earlier, there had been snow on the ground in Hot Springs, and later that afternoon, the sky would open up and unleash a cold, windy downpour. Hoyt and Mays would cut short their golf at 33 holes. Only Ruth would carry on, slugging his way through the storm, determined to get in all 36.

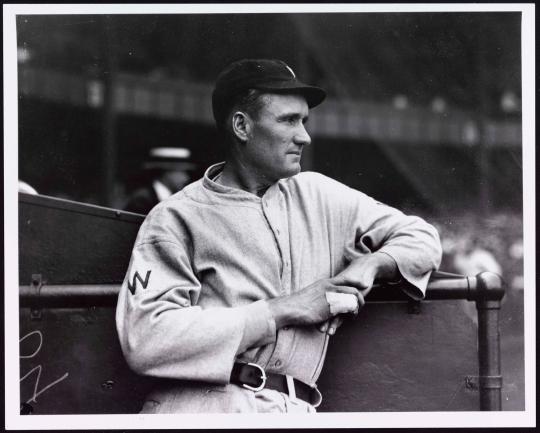

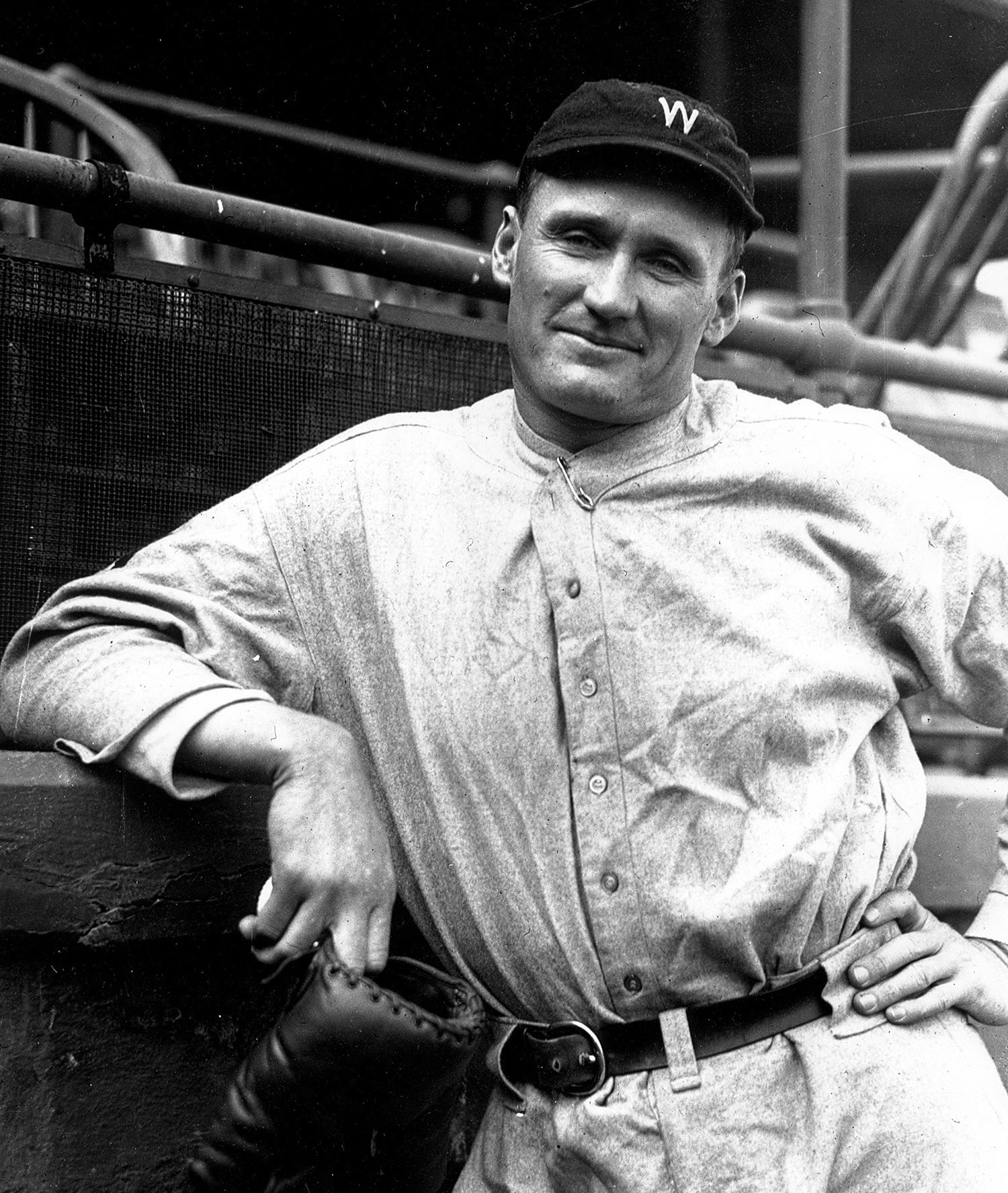

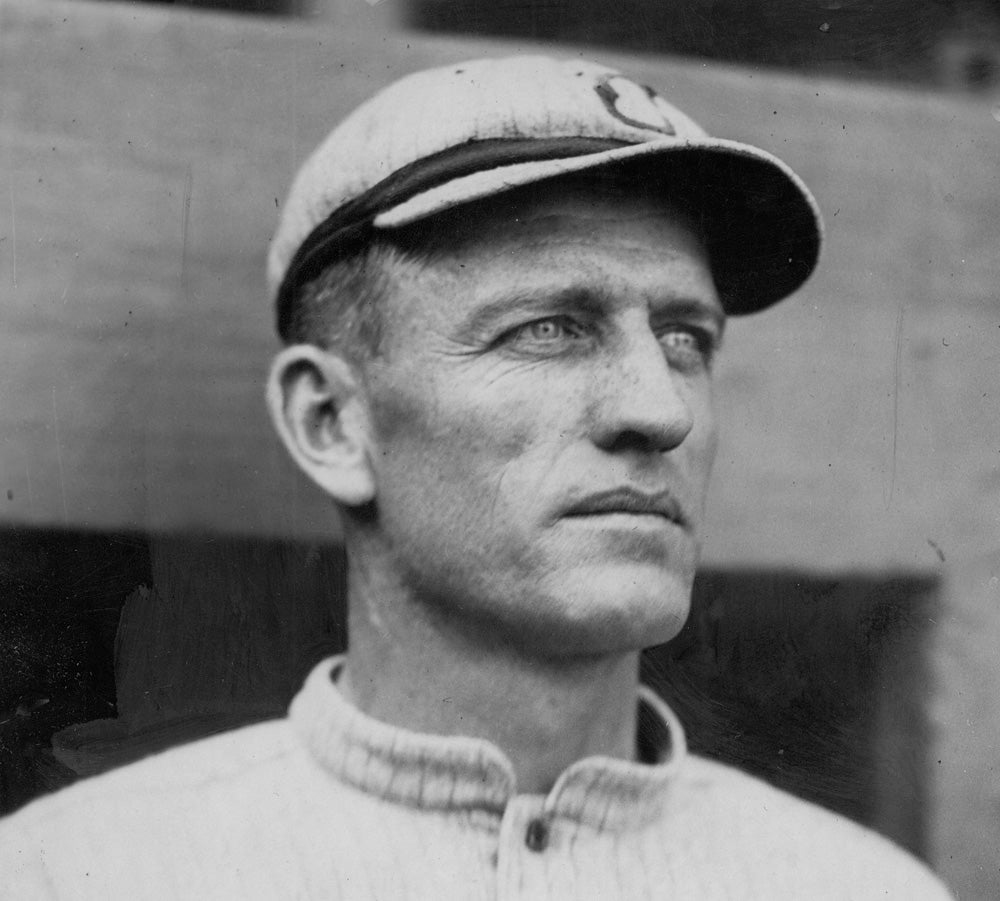

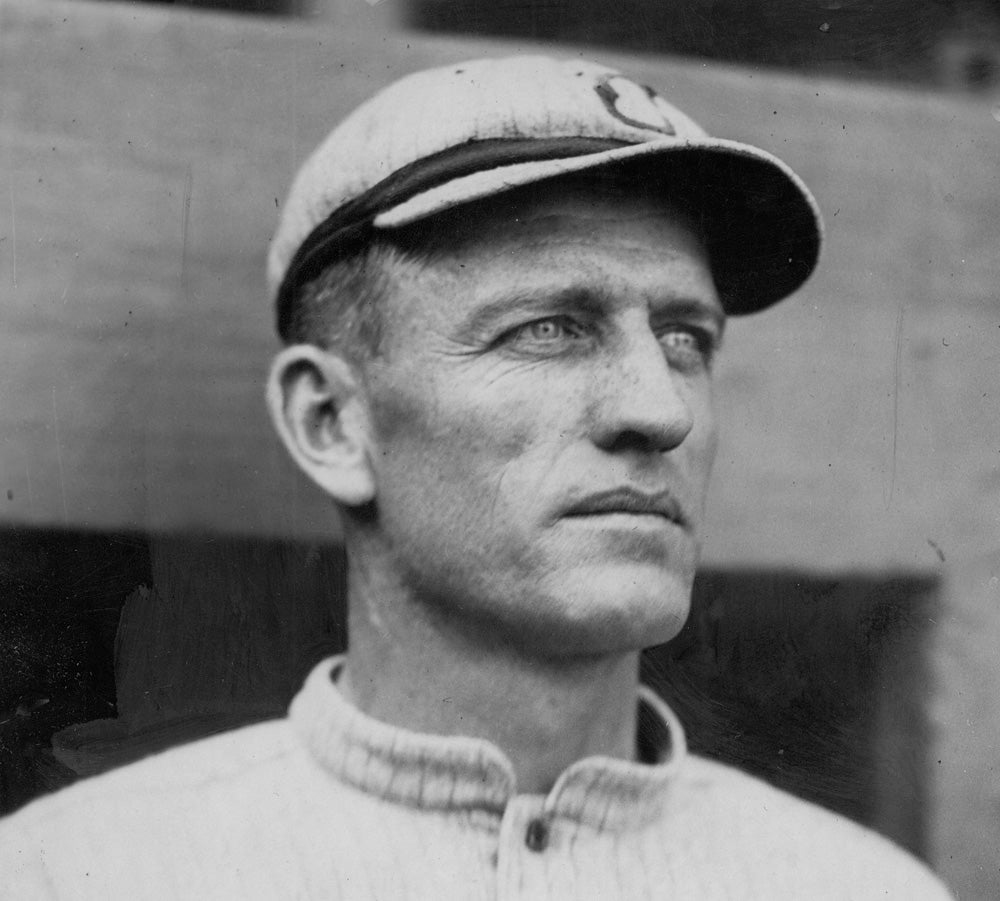

Johnson, The Big Train, appears to be trying to whisk off the boy’s hat, so the boy would appear more gentlemanly, though the photographer has fired a second too soon. It speaks to the kind of man Johnson was: polite, well-mannered, and considerate of others, quite opposite of his fastballs which Ty Cobb said “hissed with danger.”

His fastball looked about the size of a watermelon seed and it hissed at you as it passed."

Johnson appeared in Hot Springs determined to rebound from a disappointing 1920 season, when he struggled with injuries and illness. It had broken his streak of 10 straight seasons with at least 20 victories and eight seasons of leading the American League in strikeouts. He would pitch seven more seasons, finishing his Hall of Fame career with 417 wins, second only to Cy Young, and with the career strikeout record, which would stand for fifty-five years. In spite of this dominance, Johnson was humble and well-liked. Not much of a golfer, he has hiked to the course just to watch the others play.

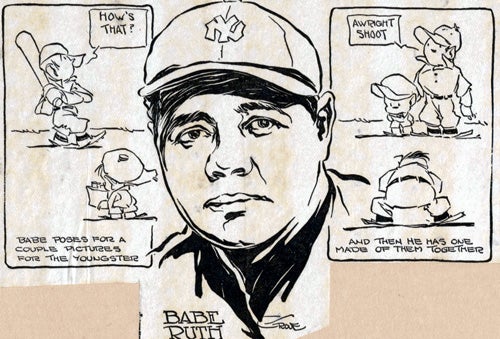

Next to Johnson is Ruth. He stands here, with wind-tousled hair, just 26 years old. He has set the single-season home run record two years in a row, finishing 1920 with a preposterous 54 home runs, more than 14 of the other 15 teams’ combined totals (Philadelphia hit 64). When he showed up in Hot Springs, the headline in the Herald was both bolded and italicized, “Season Is On!” exclamation point included, though most of the other players had been in Hot Springs for several days.

The newspaper relished his every move. He stayed up bowling with his wife until midnight. He went out for a 15-mile hike at 8 a.m. And Ruth’s weight was a matter of special scrutiny and fun. He arrived at the train station with “extra baggage.” He is “somewhat taut at the waist.” His wife is “trim and petite,” with the contrast implied.

Asked how much he weighed, Ruth replied “About 230,” and aimed to get down to 215.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

One day, the paper reported that a female “physical culturist” was confident she could help Ruth lose those pounds. Would he be interested at all? “How old is she,” Ruth asked, and the paper noted this was “a detail which did not seem to be particularly germane to the point at issue, or at tissue.” Ruth’s weight was candy for the sportswriters.

Here he stands, already a king, and yet only just beginning, about to lead the Yankees to their first pennant. He is leaning on his golf club with his left arm, twisting slightly at the hips, the left leg slightly forward. He has his tie tucked into his shirt, and wears spiffy golfing shoes. He is the only one not looking at the camera, giving him a devil-may-care appearance, or perhaps he’s merely bored.

I hope he lives to hit one hundred home runs in a season. I wish him all the luck in the world. He has everybody else, including myself, hopelessly outclassed."

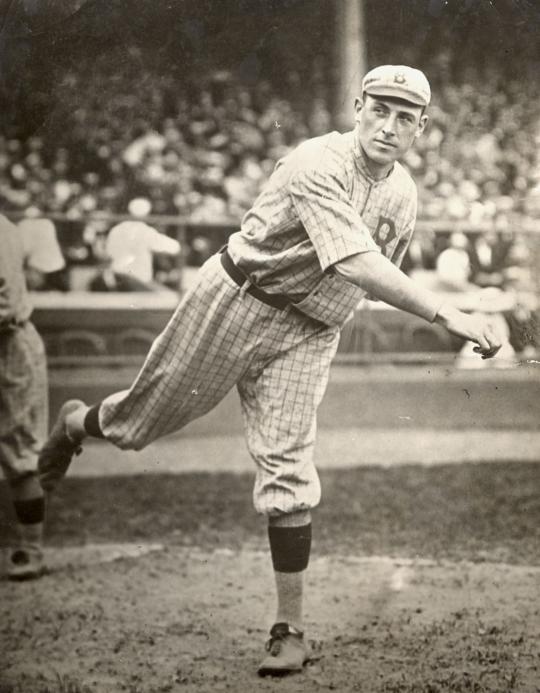

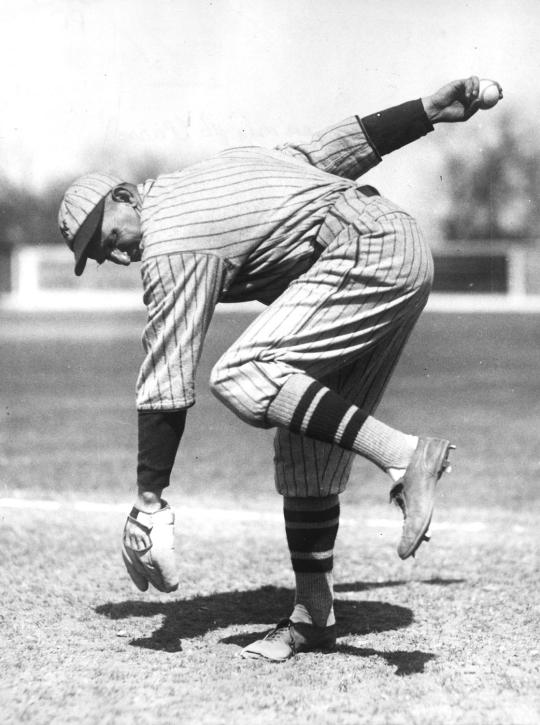

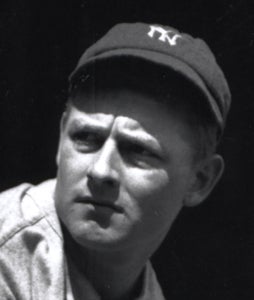

Next to Ruth, the second from the right, stands Yankee pitcher Carl Mays, perhaps the second-most talked about player in baseball in 1920, after Ruth himself. He was a brilliant pitcher, who slung the ball from a submarine delivery, the ball coming at batters from unexpected angles. He was a winner on the mound, finishing his career with 207 wins and 126 losses (.622 winning percentage) and a 2.92 ERA. But he was not liked, not by opponents, not by teammates.

He was surly, temperamental, a loner who had difficulty making friends. “I have been told I lack tact,” he once said, “which is probably true. But that is no crime.”

He’d get angry at teammates when they misplayed a ball – something Ruth had experienced firsthand. Though Ruth and Mays had been called up to the Red Sox on the same day in 1914, and had played in Boston together for five seasons and again in New York, Ruth didn’t like the man.

Mays threw pitches at batters when he was angry. One game, he threw at Cobb every time he came to bat until finally Cobb threw his bat back at him, and some suspected him of throwing games as well. His career in Boston ended when his catcher was trying to throw out a runner at second base and accidentally hit Mays in the head. Mays was so angry, he left the stadium after the inning and demanded to be traded. He was sent to the Yankees later that month.

In his first full season with the Yankees, on Aug. 16, 1920, Mays pitched to Cleveland’s popular shortstop, Ray Chapman. It was a dark day, and the ball was dirty from use. He thought that Chapman was crowding the plate, so he wound up with his submarine style and unleashed a pitch, high and tight. Witnesses say that Chapman never moved, that he never saw it coming.

Babe Ruth, from right field, said the ball connecting on Chapman’s head made an “explosive sound,” and the ball bounded back into the infield, where Mays fielded it and threw to first, apparently thinking it had struck the bat. Chapman tried to stand, then fell limp on the ground, blooding coming out of his left ear. Chapman died the next day.

Fans demanded expulsion. Teams threatened to forfeit whenever Mays pitched. After appearing before the assistant attorney general (and cleared of wrong-doing), Mays went into hiding.

Mays insisted he wasn’t throwing at Chapman – some spectators even thought the pitch might have been a strike – but no one cared to hear whatever he had to say. The pitch haunted Mays his whole life. He had ruminated all off-season, more isolated from his peers than ever.

For my own part, I have long since ceased to care what most people think of me. . . . if people don't wish to give me their good will, I am not going to beg for it."

At Hot Springs, Mays bet Ruth a box of cigars he could beat him on the golf course. “Does that guy think he can beat me at golf?” Ruth asked, with Mays standing beside him. “Want to bet another box?” No, Mays said, not another whole box. “How about half a dozen golf balls then?” No, not that either. With a five stroke handicap? No.

Both men would play in an amateur tournament in Hot Springs that February, Ruth outplaying Mays. Their private match was put off several times, and if it ever happened, it occurred after the Herald’s Hanna had moved on.

Mays stands here, squinting into the sun. His left hand is uncomfortably pressed into his front pocket, while he holds a golf ball in the right. Though it’s his pants that are most striking--cut just below the knee. At odds from everyone else’s.

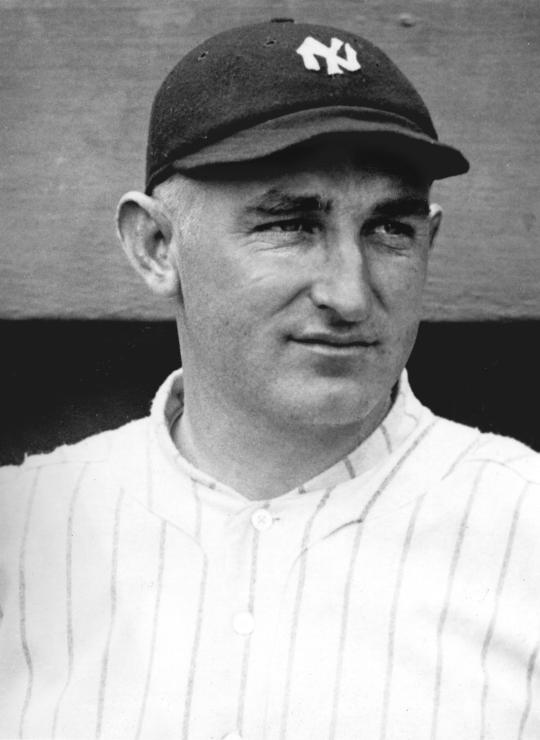

Harry Harper stands at the far right, in an unbuttoned coat, hands behind his back, a pitcher new to the Yankees, sent over by Boston in the same deal as Waite Hoyt. He has pitched in 210 games to this point; though just 26 years old, he would only pitch in nine more. Plus he had business interests to pursue; after he signed his first contract with the Washington Senators in 1913, he invested in a truck. A decade later, his trucking company would be contracted to help with the construction of the Holland Tunnel. His business was considerable, ultimately a fleet of almost a hundred trucks, and some suspected he was a self-made millionaire. He stands with a confident smile, a pocket watch chain across his vest, a pin in his lapel, his hair seemingly untouched by the wind.

Harper had started seven years before as a teammate of Walter Johnson’s. He had several successful seasons, then struggled with control. After losing a Major League leading 21 games in 1919, he was traded to Boston and became teammates with Hoyt and Mays. He continued to struggle in 1920, at one point losing ten straight decisions.

During that streak, on July 1, he faced his old mentor, Walter Johnson. Harper pitched brilliantly, but Johnson pitched better. The Big Train threw the only no-hitter of his career, winning 1-0. Johnson came over to him after the game, Harper recalled years later, and “put his arm around my shoulder. ‘I’m glad I got this one,’ he said . . . ‘I’m glad I got it, but I’m sorry it had to be you, Harry.’ . . . Oh, what a sweet guy he was.”

So here they stand, eight players on a blustery February morning in Hot Springs, Ark. Some have come to walk and exercise, some to play golf, in spite of the threat of a storm. But before they start, they listen to a photographer’s instructions, arrange themselves into a line, squint into the sun.

The eight players – of different abilities and fame, temperament and personality, of different backgrounds and with complex ties – for a single moment, pose together as one.

Larry Brunt is the Museum’s digital strategy intern in the Class of 2016 Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program for Youth Leadership Development. To support the Hall of Fame Digital Archive Project, please visit www.baseballhall.org/DAP

More #Shortstops

The Talent and the Temper of Oliver Marcelle

Jake Daubert: A miner in the majors

#Shortstops: Heroes, Hall of Famers and Sept. 11

The Voice of Babe Ruth

The Talent and the Temper of Oliver Marcelle

Jake Daubert: A miner in the majors

#Shortstops: Heroes, Hall of Famers and Sept. 11

The Voice of Babe Ruth

Related Stories

"K" as in Cain

Casey Stengel is elected to the Hall of Fame

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Easler

#CardCorner: 1990 Fleer Tom Brookens

#Shortstops: Heroes, Hall of Famers and Sept. 11

Larkin and Santo join baseball’s elite

Walter Johnson throws only career no-hitter