- Home

- Our Stories

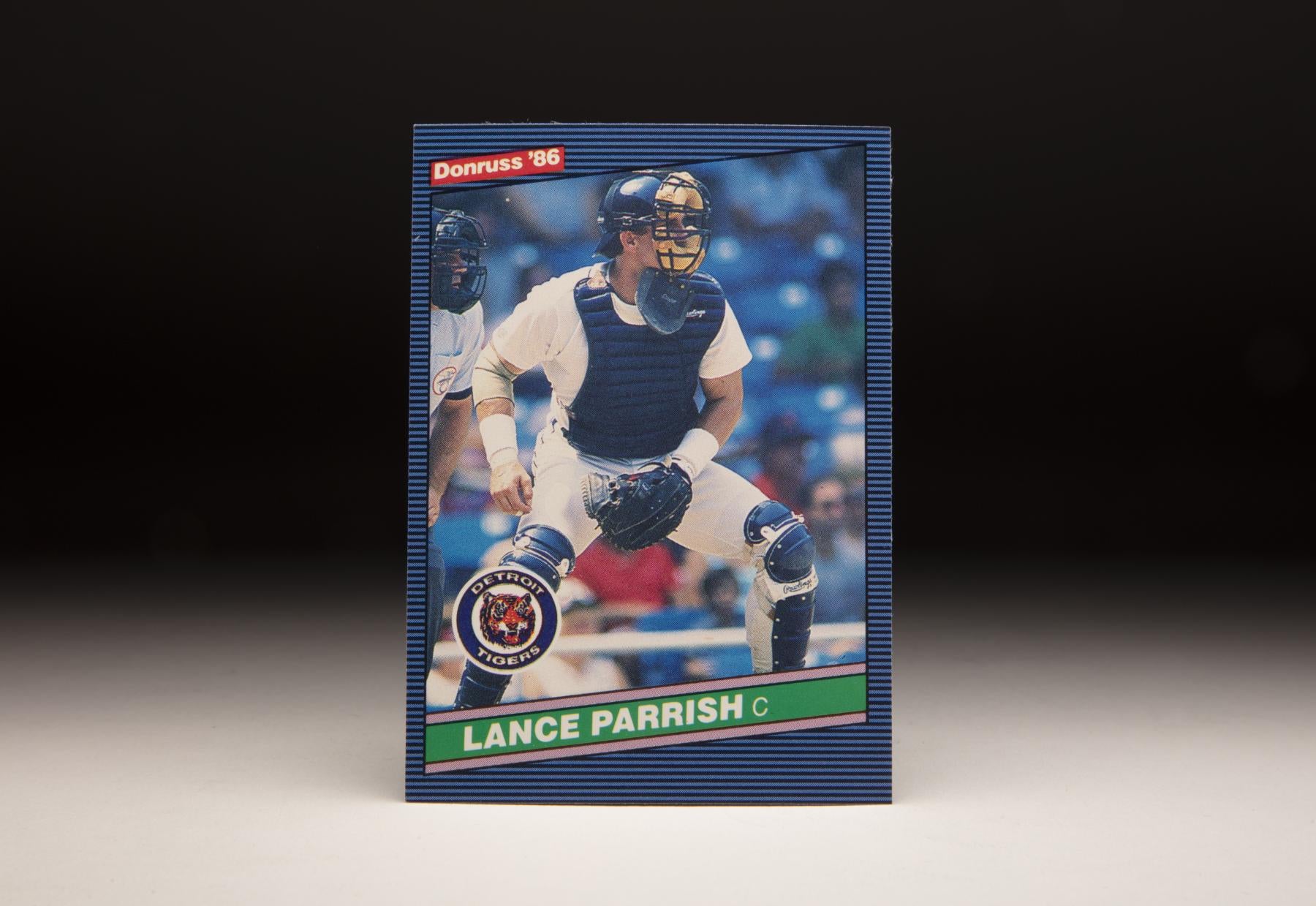

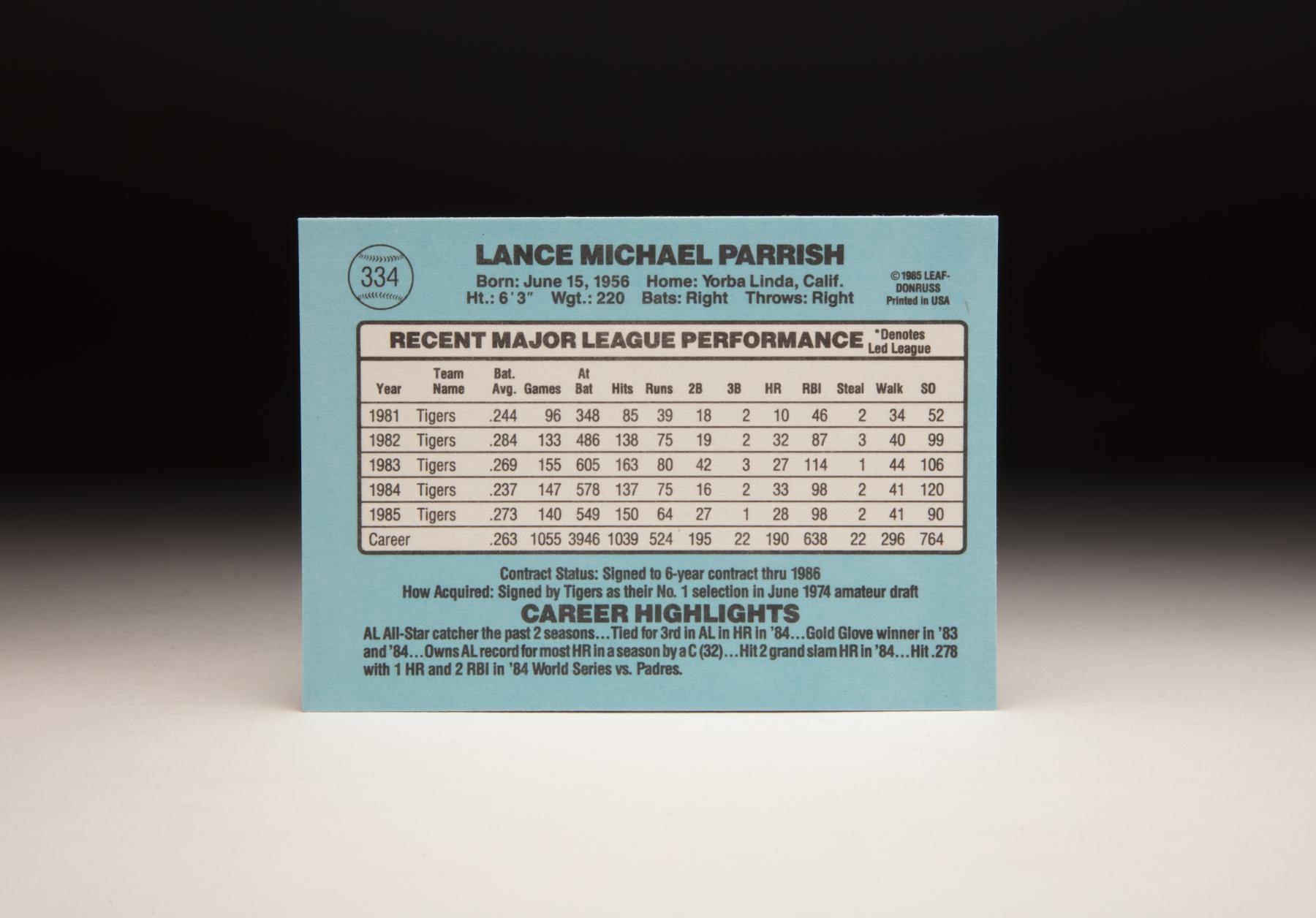

- #CardCorner: 1986 Donruss Lance Parrish

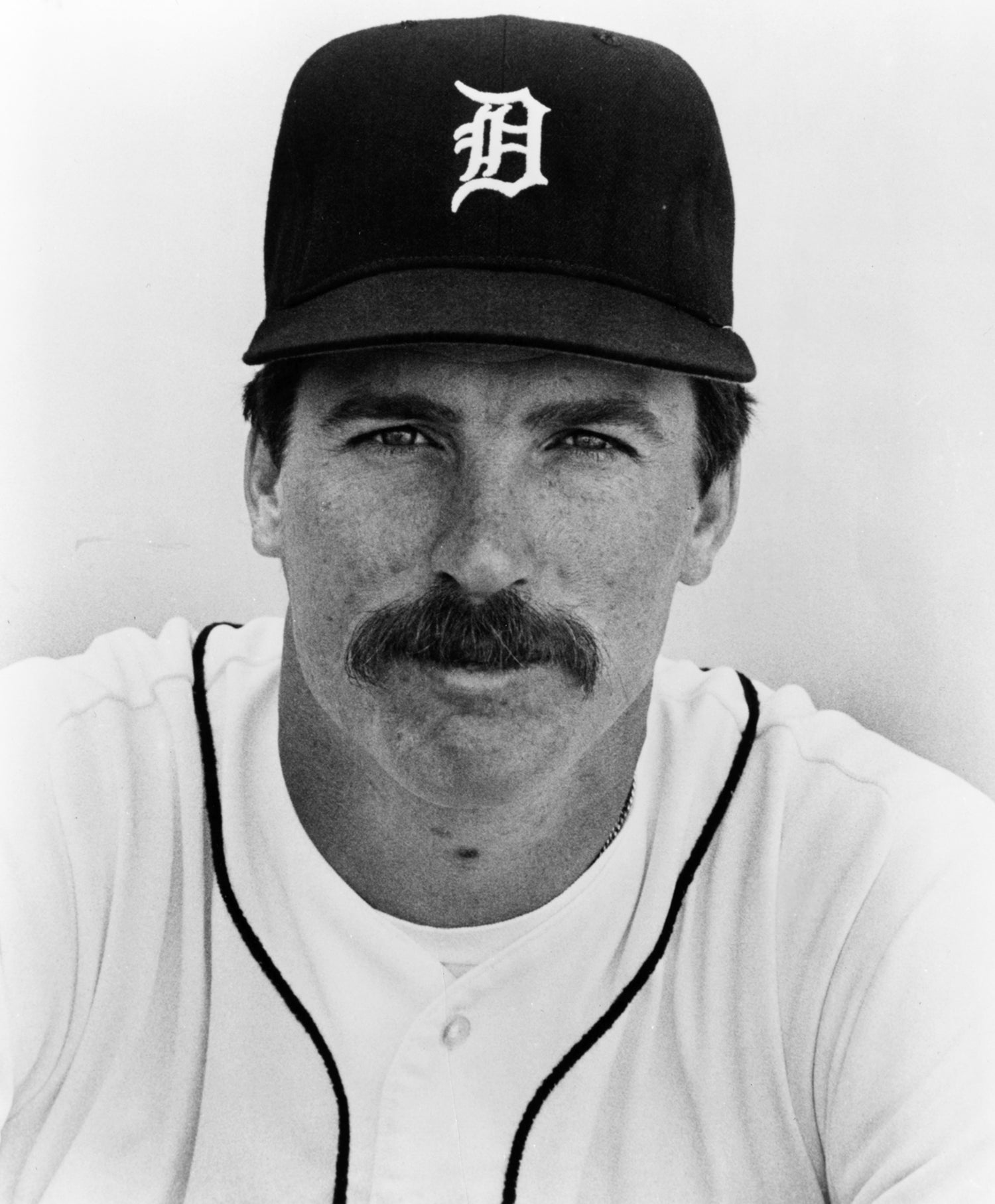

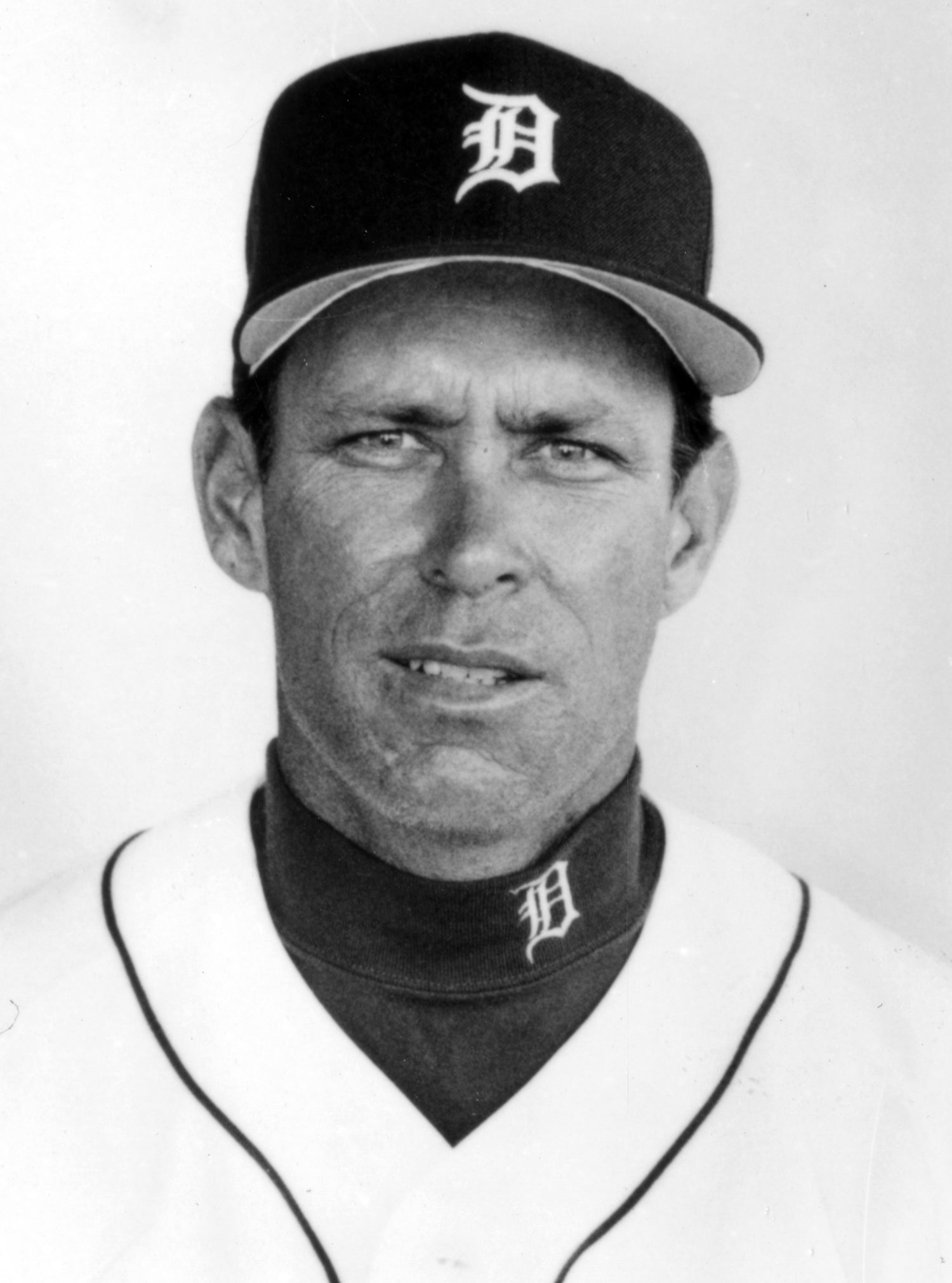

#CardCorner: 1986 Donruss Lance Parrish

Seven catchers in the game’s history have totaled at least 300 homers, 1,000 RBI and 1,000 games caught.

Six are Hall of Famers. The seventh is Lance Parrish.

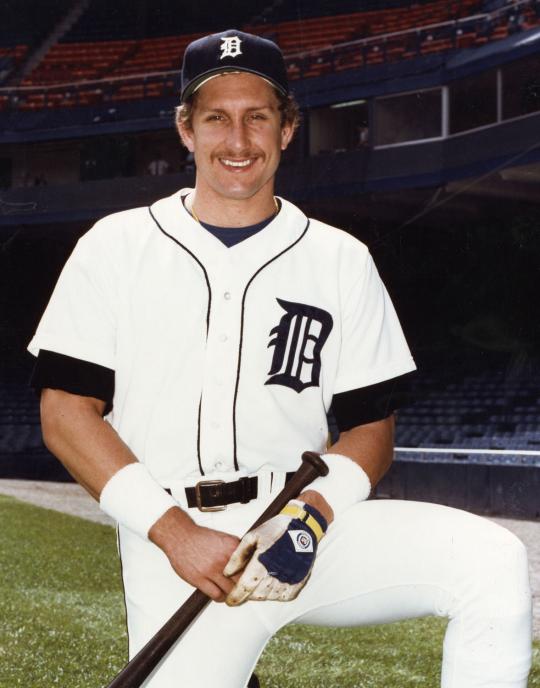

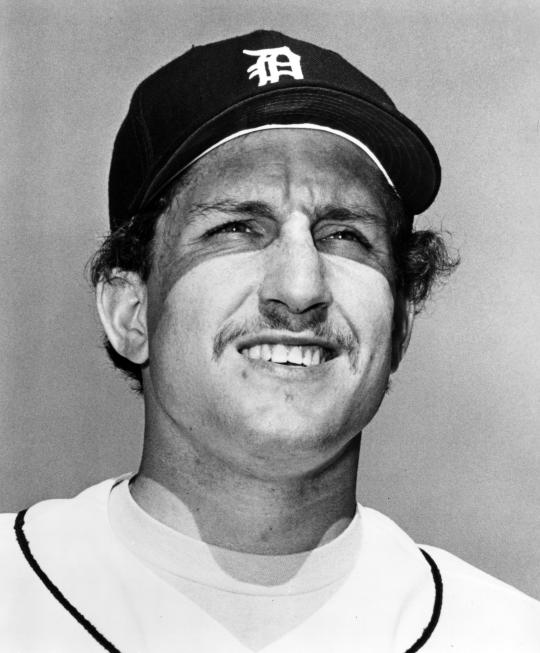

Nicknamed “The Big Wheel” because he drove the train that was the prolific Detroit Tigers’ offense of the mid-1980s, Parrish paired brute strength with an unwavering cool to become one of the most honored catchers of his era.

Born June 15, 1956, in Clairton, Pa. – about 10 minutes south of downtown Pittsburgh – Parrish moved with his family to Orange County, Calif., when he was in school. A three-year varsity football player at Walnut High School, Parrish thrived as a tight end and linebacker and was recruited by UCLA head coach Dick Vermeil.

Tigers Gear

Represent the all-time greats and know your purchase plays a part in preserving baseball history.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

“I didn’t care where I played as long as I was part of the team,” Parrish told the Baltimore Sun about his dreams to play college football.

But when the Tigers chose Parrish with the 16th overall pick in the 1974 MLB Draft and offered him a $60,000 bonus, Parrish turned to baseball even though the Angels were thought to be the team most interested in him in the pre-draft process.

Reporting to the Bristol of the Appalachian League, Parrish hit .213 with 11 homers in 68 games. He was sent to Class A Lakeland in 1975, where he moved from third base – where he spent most of his time in Bristol – to catch and hit .220 with five homers in 100 games.

Moving to Double-A Montgomery in 1976, Parrish regained some of his power and hit 14 homers in 107 games. But more importantly, Parrish established himself as a solid defender and leader on a team that won the Southern League title.

“(Montgomery manager) Les (Moss) did such a wonderful job with (Parrish),” pitcher Frank Harris, a 12-game winner with Montgomery in 1976 who never made it to the majors, told the Montgomery Advertiser after the team won the Southern League title. “He caught me last year, but he was just back there. When I came here from Lakeland this year, the first time I started getting (the ball up in the strike zone) he came out to the mound and told me he was going to beat the hell out of me if I didn’t stop it.

“Now, you don’t argue with Lance Parrish. He learned to take charge back here, and he’s helped all of us pitchers.”

The next year, Parrish played for Triple-A Evansville, where he hit .279 with 25 homers and 90 RBI to establish himself as a top prospect. The Tigers brought him to the majors in September, and he hit three home runs in 12 games down the stretch.

During that winter, Parrish’s agent arranged a deal where he served as a bodyguard for singer Tina Turner during her TV appearance in Hollywood. The story quickly got around, and no one questioned the 6-foot-3 Parrish’s qualifications as a personal protector.

“It was fun for the time it lasted,” Parrish told United Press International. “But it didn’t quite compare to trying to become a big league catcher.”

Parrish made the Tigers’ Opening Day roster in 1978 and started the team’s second game of the year. He split time with veteran Milt May that year in a lefty-righty platoon, finishing with a .219 batting average, 14 home runs and 41 RBI in 85 games against mostly left-handed pitchers.

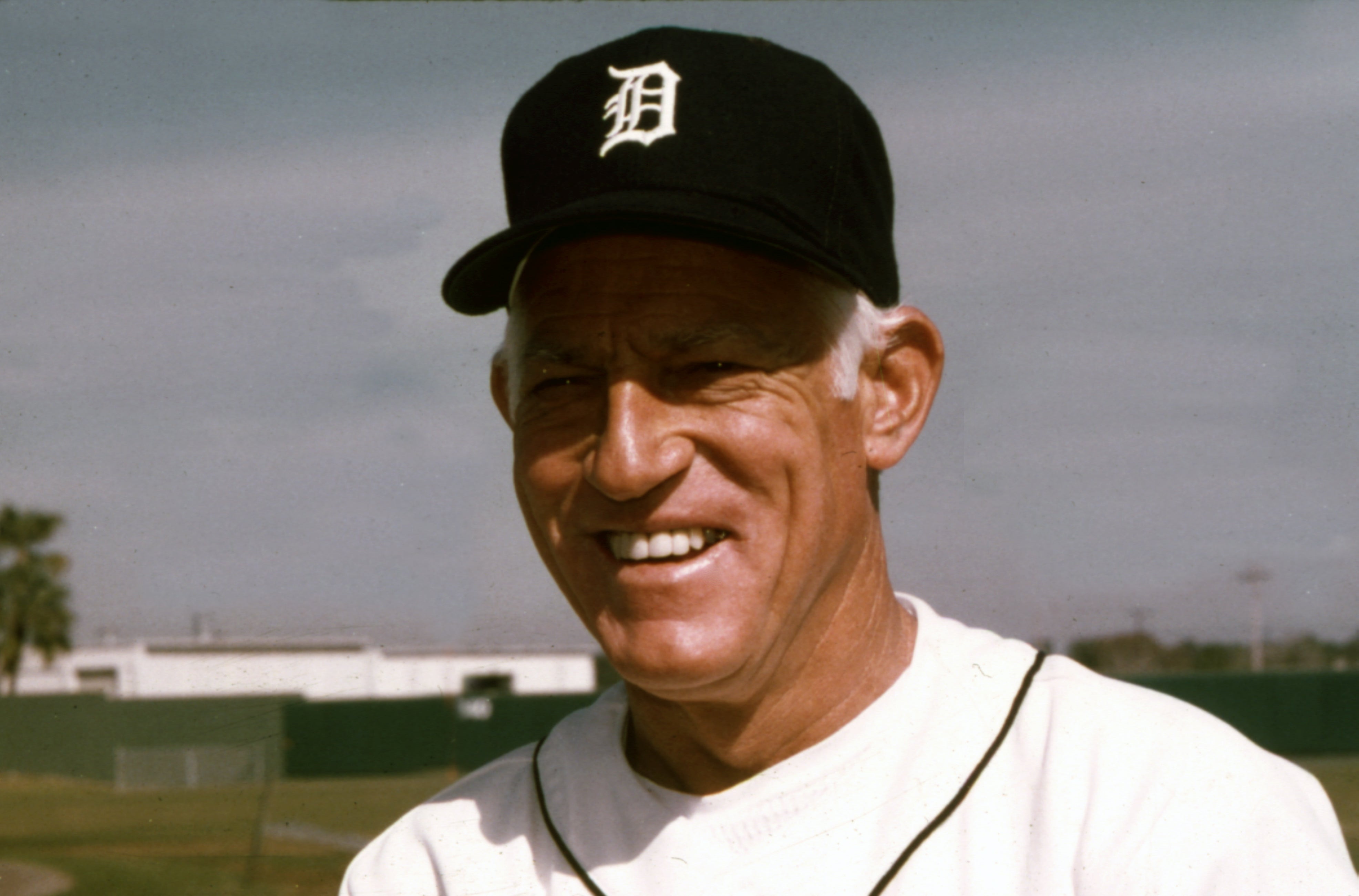

“I never saw a catcher with an arm like that,” Tigers manager Ralph Houk told UPI in the spring of 1978. “It’s only a matter of time before he’s gonna be a great one.”

In 1979, Houk’s prediction was realized. Les Moss replaced Houk as manager that year, and Parrish started on Opening Day – the first of 143 games he played that season, including 142 behind the plate. Parrish hit .276 with 19 homers and 65 RBI. And though he led the league with 21 passed balls, he also threw out 57 runners – the second-best total in the league.

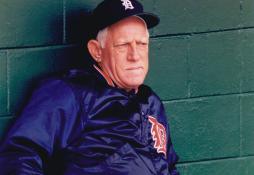

Moss did not make it through the season, being replaced by Sparky Anderson in June. The former Reds manager found himself with a bushel of young talent, including Alan Trammell, Jack Morris, Lou Whitaker, Kirk Gibson and Parrish. That group would form the nucleus of the Tigers team that would win the World Series in 1984.

Parrish injured his elbow in Spring Training of 1980, a condition that curtailed his postgame weightlifting sessions but not his playing time. He appeared in 54 of the Tigers first 55 games and finished with a .286 batting average, 34 doubles, 24 home runs and 82 RBI. Earning his first All-Star Game selection, Parrish also won a Silver Slugger Award while he worked on improving a caught stealing percentage that dropped to 38 percent – seven points lower than the year before.

“I don’t care what Lance does at the plate,” Anderson told the Detroit Free Press. “Defense is the No. 1 thing with a catcher and hitting is No. 2.”

Parrish’s batting wasn’t as strong in 1981 as he hit .244 with 10 homers and 46 RBI in 96 games. But he was second in the AL among catchers with 33 caught stealings as his defense continued to improve.

On May 29, 1981, Parrish signed the richest contract in Tigers history – agreeing to a six-year, $3.7 million deal that would carry him through the 1986 season.

In 1982, Parrish brushed aside a hand injury that sidelined him for two weeks in April by putting together another All-Star season. He hit .284 with 32 home runs – a new AL record for catchers – and 87 RBI, earning his second berth in the Midsummer Classic – where he threw out three runners trying to steal despite not entering the game until the fifth inning.

Parrish won the first of three consecutive Silver Slugger Awards that season, finished 13th in the AL Most Valuable Player voting and ranked second among AL catchers by erasing 46 percent of the runners who tried to steal.

“I believe Lance Parrish is the best player in America – including Mike Schmidt, who is a pretty fair ballplayer,” Anderson told the Associated Press in Spring Training of 1983.

The 1983 season proved Anderson correct. Parrish hit .269 with 42 doubles, 27 homers and 114 RBI while earning another All-Star Game selection, his first Gold Glove Award and a ninth-place finish in the AL MVP voting. He led all big league catchers by throwing out 48.6 percent of runners who attempted to steal – in a season where Rickey Henderson stole 108 bags and Rudy Law finished second in the league with 77.

Parrish continued to work with weights during this time and finally earned the approval of his manager. In 1982, Anderson removed the weight equipment from the workout room at the team’s Spring Training home in Lakeland, Fla., because he thought Parrish’s workouts would leave him musclebound – something that was then frowned upon in baseball. Parrish countered by offering to quit lifting weights if he had a poor season in 1983. But if he was successful, he asked Anderson to let him train as he saw fit.

After Parrish’s incredible 1983 campaign, Anderson halted his protestations.

“When there’s a runner on first, you don’t have to give him too much thought with Lance in there,” Tigers pitcher Dan Petry told the Baltimore Sun. “When I first came here, Jack Billingham told me about Johnny Bench and how he didn’t have to throw over (to first) when Bench was catching. I never saw Bench, but I know what he means now.”

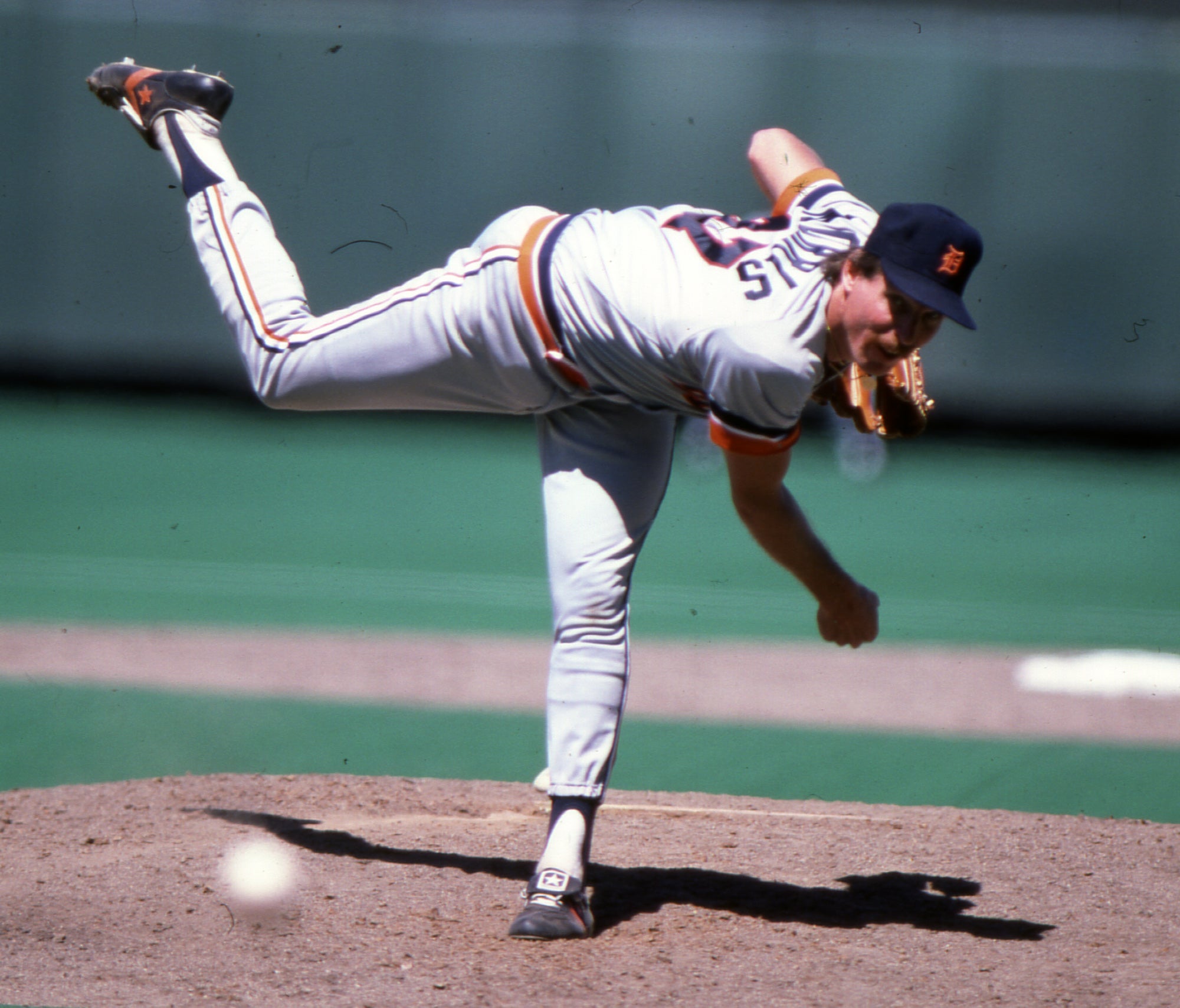

The Tigers, who had been assembling a talented team since Anderson arrived in 1979, put it all together in 1984 by bolting to a huge lead in the AL East and winning the division easily. Batting cleanup in every game he started, Parrish led the Tigers with 33 home runs and 98 RBI. And though his average dropped to .237, Parrish won another Gold Glove Award while establishing himself as a strong-willed clubhouse presence.

“He’s a quiet leader,” Tigers pitching coach Roger Craig told the Baltimore Sun in 1984. “There are some guys who’ll come in here and say something and eight or 10 others will be talking. But when Lance walks in and says: ‘Hey guys, I want to talk to you for a few minutes,’ you can hear a pin drop.”

Parrish also became well known for helping Jack Morris control his legendary intensity. He caught Morris’ no-hitter on April 7, 1984, against the White Sox and earned Morris’ praise throughout their time in Detroit.

“I love the guy,” Morris told the Los Angeles Times. “He’s got so much more class than I do at times.”

Parrish drove in two runs in Game 1 of the ALCS vs. the Royals with a sacrifice fly and a homer as Detroit set the tone en route to a sweep with an 8-1 win. Then in Game 5 of the World Series vs. the Padres, Parrish’s seventh inning home run off Goose Gossage gave the Tigers a 5-3 lead, which became an 8-4 Detroit win after Kirk Gibson’s legendary three-run shot in the eighth.

When Willie Hernández recorded the final out of the World Series a few minutes later, Parrish ran to the mound and leapt into the air – a photo of which ran in papers around the country the next day.

It would mark the peak of Parrish’s career and the only time his team would advance to the postseason.

Parrish had another stellar season in 1985 by hitting .273 with 28 homers and 98 RBI while winning his third and final Gold Glove Award. But with his contract set to expire after the 1986 season, Parrish appeared in only 91 games that year. An .824 OPS indicated Parrish was as dominant as ever at the plate when healthy – and he started the All-Star Game for the second time that summer.

But with a free agent marketplace that was eventually ruled limited by collusion, Parrish and other free agents found limited opportunities that winter. After a two-month negotiation with Philadelphia, Parrish agreed to a one-year deal with the Phillies that would pay him $1 million provided he stayed healthy.

Parrish played in 130 games that year but hit just 17 home runs, his lowest total since becoming a regular in 1979. Agreeing to another one-year deal with Philadelphia for the 1988 season, he earned his seventh All-Star Game selection but hit just .215 with 15 home runs in 123 games.

An arbitrator ruled that Parrish could be a “new look” free agent following the season, but Parrish reportedly waived that right when the Phillies traded him to the Angels for pitcher David Holdridge on Oct. 3, 1988. Parrish quickly signed a one-year deal worth $1 million that also brought him about $200,000 in incentives. He hit .238 with 17 homers and 50 RBI in 1989 then was once again made a free agent when an arbitrator declared that he had previously not waived his “collusion” rights.

Parrish, however, lived just down the road from his home ballpark in Yorba Linda, Calif., and had no desire to leave the Angels. On Dec. 13, 1989, Parrish signed a new three-year, $6.75 million deal.

“I really wasn’t interested in going someplace else,” Parrish told the Orange County Register. “I’m hoping to play well with this club, contribute to its success and then hopefully sign a couple more contracts with them.”

Parrish had his last All-Star season in 1990, earning his eighth selection to the Midsummer Classic and sixth Silver Slugger Award while hitting .268 with 24 homers and 70 RBI while leading all AL catchers with 88 assists. But 1991 saw Parrish hit just .215, and in 1992 the Angels released him on June 23 after appearing in just 24 games. He quickly signed with Seattle and played out the season with the Mariners.

In 1993, Parrish signed with the Dodgers but was released before appearing in a game, then moved on to Cleveland where he played in 10 games before being cut. Returning to the Tigers in 1994, Parrish did not make the Opening Day roster and was sent to Triple-A before his contract was sold to the Pirates in April. He played in 40 games in that strike-shortened season before hooking on with Toronto as a backup in 1995, hitting .202 in 70 games in his last big league campaign. He went to camp with the Pirates in 1996 but was not included in the final roster, a move that ended his playing days.

Parrish was on the Tigers’ coaching staff from 1999-2001, called Tigers games on TV in 2002 and then returned to the coaching staff from 2003-05. He later served as a manager in the team’s minor league system.

He finished his career with 324 home runs, 1,070 RBI and 1,818 games caught (which ranks 13th all-time). Among players with at least 1,000 games at catcher, only Hall of Famers Johnny Bench, Yogi Berra, Gary Carter, Carlton Fisk, Mike Piazza and Iván Rodríguez have at least 300 homers and 1,000 RBI. And of those six Hall of Famers, only Bench, Carter and Rodríguez also won multiple Gold Glove Awards.

Few catchers have ever combined all phases of the game like the former high school linebacker from Southern California.

“I feel like I’m on the right track but I’ve never felt like I’m the complete player,” Parrish said during the Tigers’ championship season of 1984. “I’m either hitting the ball good and catching not so good or catching good and hitting not so good. One of these days, I’m going to get the two of them together.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Morris’ no-hitter gets Tigers’ historic ’84 season rolling

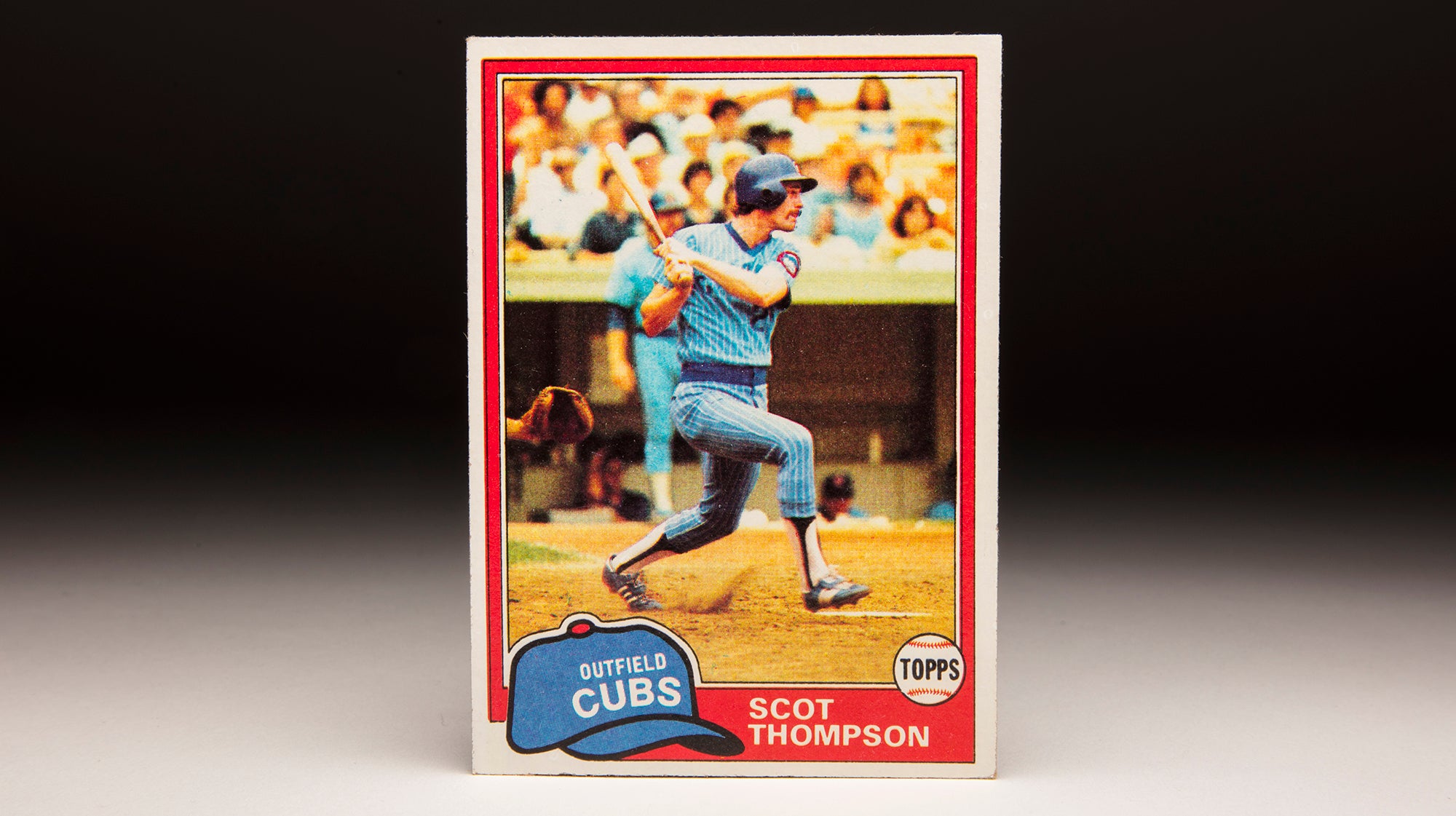

#CardCorner: 1981 Topps Scot Thompson

Sparky Anderson becomes first manager to win 100 games in both leagues

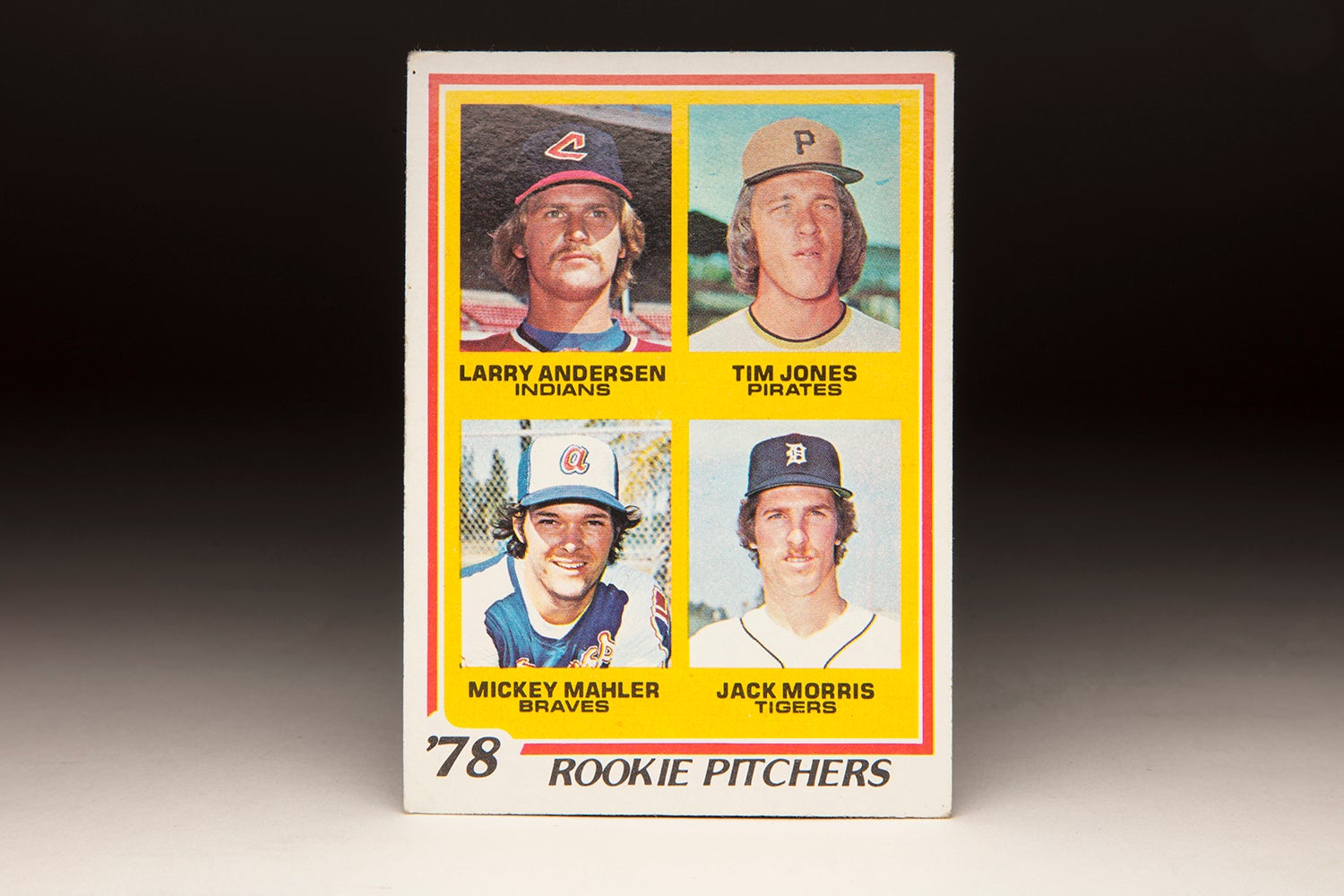

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Rookie Pitchers

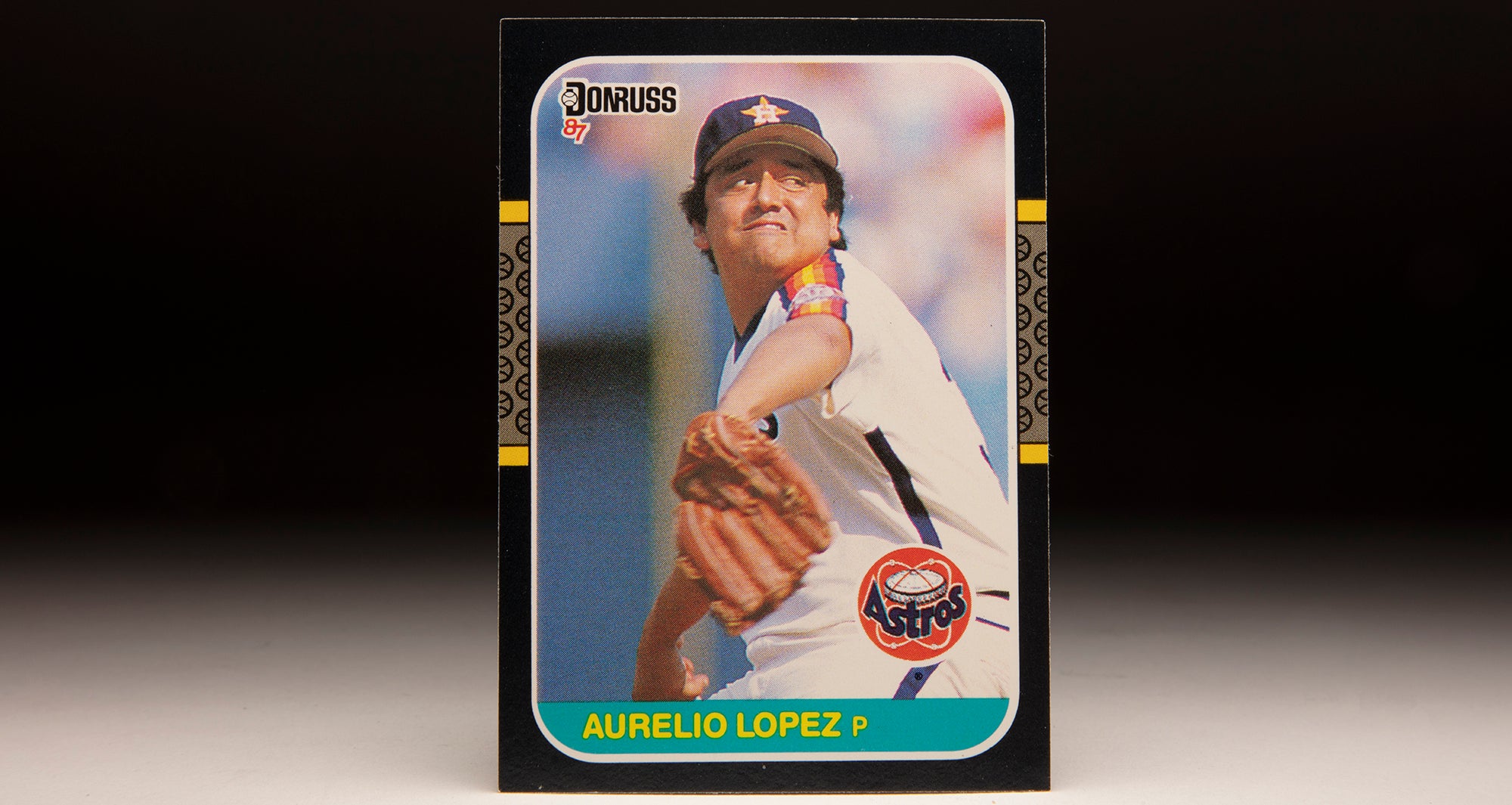

#CardCorner: 1987 Donruss Aurelio López

Related Stories

Time to PLAY Ball

Stargell blasts longest home run in Olympic Stadium history

#CardCorner: 1975 Topps Elias Sosa

#CardCorner: 1990 Fleer Tom Brookens

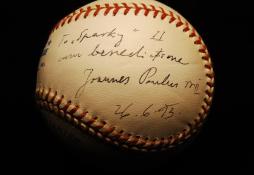

The Holy Ball: Sparky and the Pope

Sparky Anderson becomes first manager to win 100 games in both leagues

Astrodome barely contains Mike Schmidt’s blast

#CardCorner: 1982 Topps Bill Campbell

Two-Time MVP, Brewers Legend Robin Yount Joins Lineup for May 23 Hall of Fame Classic

01.01.2023