- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1984 Topps Manny Trillo

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Manny Trillo

It was the height of the chaos that was the Swinging A’s of the 1970s, where controversy and disruption seemed to fuel a dynasty.

And Manny Trillo had a front row seat.

A native of Caripito, Venezuela, Trillo had played in just 17 big league games when he was thrust into the national limelight during the 1973 World Series. Fortunately for Trillo, the rest of his stellar big league career made that moment in time a mere footnote in his biography.

Born on Christmas Day in 1950, Jesús Manuel Marcano Trillo was raised by his mother and began his amateur career as a shortstop, following in the footsteps of Venezuelan heroes Chico Carrasquel and Luis Aparicio. But when his youth league team needed a catcher, Trillo found himself behind the plate.

“One day the catcher got hurt and they made me catch,” Trillo told the Tucson Daily Citizen. “I sure didn’t want to do that. I cried the rest of the game when I was back there. But I had a real good arm then.”

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

Trillo even dabbled on the mound in those days but eventually settled in as a catcher. He was mentored by Pompeyo Davalillo, who played with the Washington Senators in 1953 and became legendary for developing talent in his home country.

A month after his 17th birthday, Trillo signed with the Phillies.

“After two years in college, I said I had enough,” Trillo told the Daily Citizen when he was playing in the minor leagues in 1973. “I didn’t want to do that anymore. I wanted to play baseball.”

The Phillies sent Trillo to Huron, S.D., of the Northern League, where he hit .261 in 35 games while learning a new language and culture. Manager Dallas Green quickly moved Trillo from behind the plate to the infield – a decision that would benefit Green and Phillies fans a decade later.

Trillo played for Class A Spartanburg of the Western Carolinas League in 1969, hitting .280 in 83 games as an 18-year-old. Following the season, the Athletics selected Trillo in the minor league Rule 5 Draft.

Oakland assigned Trillo to Birmingham of the Southern Association in 1970, and Trillo hit .261 in 84 games while rotating between second base, third base and shortstop. He returned to Birmingham in 1971, where he hit .280 while playing the majority of his games at third.

Then in 1972, Trillo firmly thrust himself onto the Athletics’ radar when he hit .301 with 27 doubles for Triple-A Iowa. With All-Star Sal Bando and Bert Campaneris entrenched for Oakland at third base and shortstop, respectively, Trillo was told in Spring Training of 1973 that he should concentrate on learning second base.

“It’s still new to me,” Trillo told the Daily Citizen. “Starting a double play is nothing. I can do that. But I have trouble with the relay.”

Trillo’s fast hands made him a natural at the position, however, and his bat continued to improve as he stayed among the Pacific Coast League leaders in hitting all year – finishing at .312 with 25 doubles and 78 RBI in 135 games.

The A’s, meanwhile, were employing one of the most unique second base arrangements in the game’s history. Owner Charlie Finley had ordered manager Dick Williams to pinch hit for starter Dick Green – a superb fielder who finished his 12-year career with a .240 batting average – in every key situation. The result was a carousel of players at second base, including catcher Gene Tenace.

Oakland won the American League West for the third straight season in 1973, and Finley placed Trillo on the ALCS roster despite the fact that he was not on the Athletics’ roster by Sept. 1 as mandated by league rules. This came after Finley sold the contract of Jose Morales to the Expos on Sept. 18.

The Orioles, however, did not protest and allowed the move, though Trillo did not see any action during Oakland’s five-game victory.

But the Mets – who had won the National League pennant – refused to allow the Trillo for Morales switch in the World Series. As a result, the A’s had only 24 players to choose from – and were already without injured starting center fielder Billy North, who was replaced on the roster by pinch running specialist Allen Lewis.

“A lot of people say to me: ‘You are along for a vacation,” Trillo, who traveled with the A’s during the World Series, told the Des Moines Tribune. “They think I like the vacation. I’ll tell you, I’d like to be in the World Series for one inning…for one turn at bat.”

Trillo nearly got his wish. In Game 2, Williams had pinch hit for both Green and backup Ted Kubiak by the time the 12th inning began. Mike Andrews, a former All-Star with Williams with the Red Sox in the late 1960s who had signed as a free agent with the A’s in July, was at second base. After the Mets had taken a 7-6 lead on a Willie Mays single, Andrews was charged with errors on consecutive plays – allowing three runs to score in what became a 10-7 Oakland loss.

Following the game, Finley claimed that Andrews had an injured shoulder – and asked MLB to approve replacing Andrews with Trillo on the active roster. The A’s players nearly revolted.

“It lacked a lot of class,” Bando told the Associated Press, noting that he was sure Williams “had nothing to do with the departure of Andrews.”

During an off-day workout between Games 2 and 3 at Shea Stadium on Monday, Oct. 15, many Athletics players – including Trillo – taped Andrews’ No. 17 on their shoulders with adhesive tape to protest Finley’s move. An Associated Press photo of Trillo and Vic Davalillo – Pompeyo’s brother – with the No. 17 taped on their jerseys ran in newspapers around the country.

Commissioner Bowie Kuhn quickly ruled that Andrews would have to be reinstated, and Trillo did not play in the World Series. He was, however, part of a championship team as the Athletics defeated the Mets in seven games. Williams, angered by the Andrews/Trillo flap and many other incidents, resigned following the World Series.

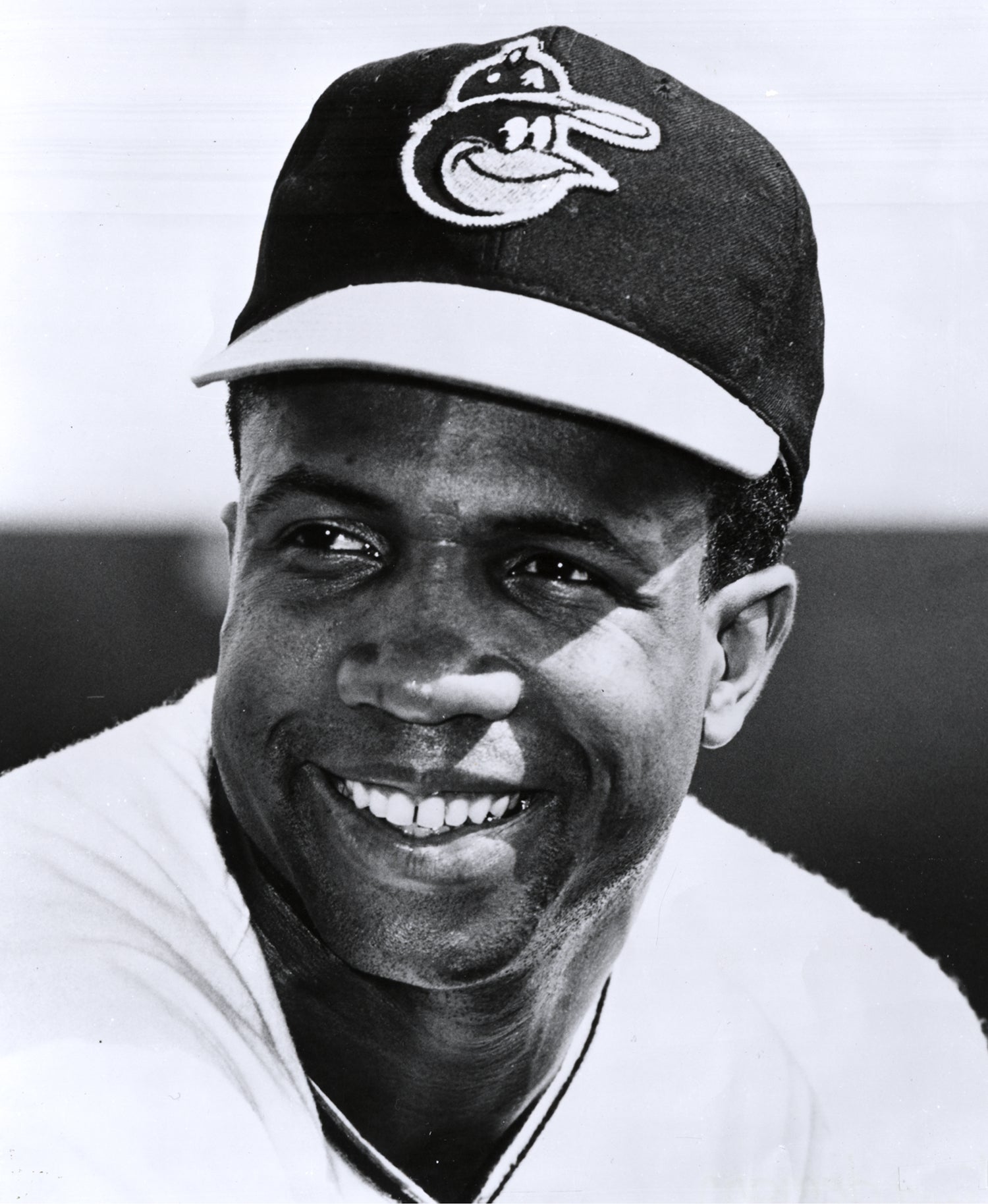

Trillo started the season with Oakland in 1974 but was quickly returned to Tucson – the A’s continued to use Green and Kubiak at second base under new manager Alvin Dark – and played just 21 games for the A’s that year. He was on the roster for both the ALCS and World Series, however, and pinch ran for Jesús Alou in Game 1, scoring a run in Oakland’s 6-3 loss to Baltimore. It would be the only game he would play in the 1974 postseason.

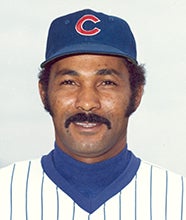

On Oct. 23 – just six days after the A’s won their third straight World Series title – Trillo was traded to the Cubs along with Darold Knowles and Bob Locker in exchange for future Hall of Famer Billy Williams.

Cubs general manager John Holland called Trillo the key to the deal, and Trillo was immediately installed as the team’s second baseman. In 154 games in 1975, Trillo batted .248 but drove in 70 runs and led all NL players with 509 assists. He was also charged with 29 errors – a number that did not prevent him from finishing third in the NL Rookie of the Year balloting.

Trillo cut his errors to 17 in 1976 while increasing his assists total to a league-best 527 while hitting .239 with 59 RBI and 17 steals in 158 games. His numbers in the field and at the plate remained steady over the next two seasons, with his batting average going up while his range slightly decreased.

A 1977 All-Star, Trillo had established himself as one of the most dependable second basemen in the game and led NL second basemen in assists each year from 1975-78.

Then on Feb. 23, 1979, the Phillies – who had won three straight NL East titles only to lose in the NLCS each season – sent five players, including starting second baseman Ted Sizemore, to the Cubs in exchange for Trillo, Greg Gross and Dave Rader.

“I think you’re going to have to go a long while before you have a better infield than ours,” Phillies general manager Paul Owens – who had brought Pete Rose to the Phillies as a free agent that offseason – told the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Success did not come immediately for the Phillies, however, as Philadelphia finished fourth in the NL East. Trillo suffered a fractured left forearm in May and a groin injury in September, limiting him to 118 games. But he committed just 10 errors in 648 chances and earned the first Gold Glove Award of his career in a season where he batted .260 with 42 RBI.

But as difficult as things were in 1979, it all came together in 1980. Trillo hit .292 in 141 games and finished second in the league with 467 assists, helping Philadelphia reclaim the NL East title. In the NLCS, his sacrifice fly in the eighth inning of Game 4 – with the Phillies trailing the Astros 2-games-to-1 and 2-0 on the scoreboard entering the frame – gave Philadelphia a 3-2 lead. After Houston tied the game in the bottom of the ninth, Trillo’s double in the 10th inning tacked on an insurance run in the Phillies’ 5-3 win.

In Game 5 the following day, Trillo’s two-out, two-run triple in the eighth inning broke a 5-5 tie. The Phillies held on to win 7-5 to advance to their first World Series since 1950 – and Trillo was named NLCS MVP.

“I was kept out of the Series twice with Oakland,” Trillo told United Press International. “I was really looking forward to this one.”

In the World Series against the Royals, Trillo proved the different in the critical Game 5. With the series tied at two games apiece, his relay throw to home plate on a sixth-inning Willie Wilson double nailed Darrell Porter, keeping the score 3-2 in favor of the Royals and effectively snuffing out a Kansas City rally.

Then in the ninth inning – with the score 3-3 and Del Unser on third base following his game-tying RBI double – Trillo lined an 0-2 pitch off the tip of the glove of Royals ace reliever Dan Quisenberry. Trillo beat out an infield hit on the play, allowing Unser to score with what became the winning run.

Philadelphia went on to win the World Series in Game 6 – the first title in Phillies history.

“He threw me two fastballs and then a slider,” Trillo said of the sequence against Quisenberry. “The only thing I was thinking was to make contact. I hit the slider on the end of the bat and it went through the middle.”

But for many, Trillo’s relay throw in the sixth inning was the play of the series.

“We wouldn’t even have been in the game if Manny Trillo hadn’t made the perfect throw to get Porter,” Phillies first baseman Pete Rose told UPI. “If he doesn’t make that play, they could have gone onto a big inning and taken us right out of the game.”

Trillo, who signed a four-year contract worth a reported $1.5 million prior to the 1980 season, was now one of the most highly regarded second basemen in baseball. In 1981, he was named to the first of three straight All-Star Games, won his second Gold Glove Award and even captured a Silver Slugger Award, hitting .287 over 94 games in that strike-shortened season. The Phillies won the NL East first half title but lost to the Expos in five games in the division series, ending their reign atop the baseball world.

Trillo won his third-and-final Gold Glove Award in 1982, setting a new record by going 479 chances without an error over 89 games, falling two games short of Joe Morgan’s then-record for second basemen. But the Phillies fell to second place in the division. Then on Dec. 9, 1982, Trillo was involved in one of the most famous trades of the decade when Philadelphia sent five players – Jay Baller, Julio Franco, George Vukovich, Jerry Willard and Trillo – to the Indians for Von Hayes.

“I’m flattered to be traded for someone like Manny Trillo,” Hayes told the Associated Press. “He’s one of the best second basemen in the game. It would have been a fair swap if they had traded me for Trillo straight up.”

But with Trillo’s contract set to expire after the 1983 season, the Indians did not envision Trillo in their long-range plans. After hitting .272 in 88 games, Cleveland traded Trillo to the Expos on Aug. 17, 1983, for minor leaguer Don Carter and $300,000.

Trillo hit .264 in 31 games for Montreal and then became a free agent. He signed a three-year-deal with the Giants on Dec. 20, 1983, but missed two months during the 1984 season with a fractured left hand and finished the year with a .254 batting average in 98 games.

In 1985, the Giants lost 100 games and Trillo hit just .224, his lowest batting average since becoming a regular in 1975. On Dec. 11, 1985, the Giants traded Trillo to the Cubs in exchange for Dave Owen. It was the start of a transition away from a starting role for Trillo, who spent the next three seasons in a reserve role for Chicago – seeing action at first base for the first time in his career. Following the 1988 season, Trillo signed a one-year deal with the Reds worth a reported $320,000. The move reunited Trillo with Rose, who was managing Cincinnati. But after hitting .205 in 17 games, the Reds released Trillo on May 25, 1989. He would not play in the big leagues again. Trillo worked as a minor league instructor for years and also continued to coach young players in Venezuela. He finished his 17-year big league career with 1,562 hits, a .263 batting average, four All-Star Game selections and three Gold Glove Awards. As good as Charlie Finley thought Trillo might be in 1973, Trillo proved he was even better. “He’s an outstanding defensive player,” Giants manager Frank Robinson said when Trillo signed with San Francisco, “if not the best second baseman around.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

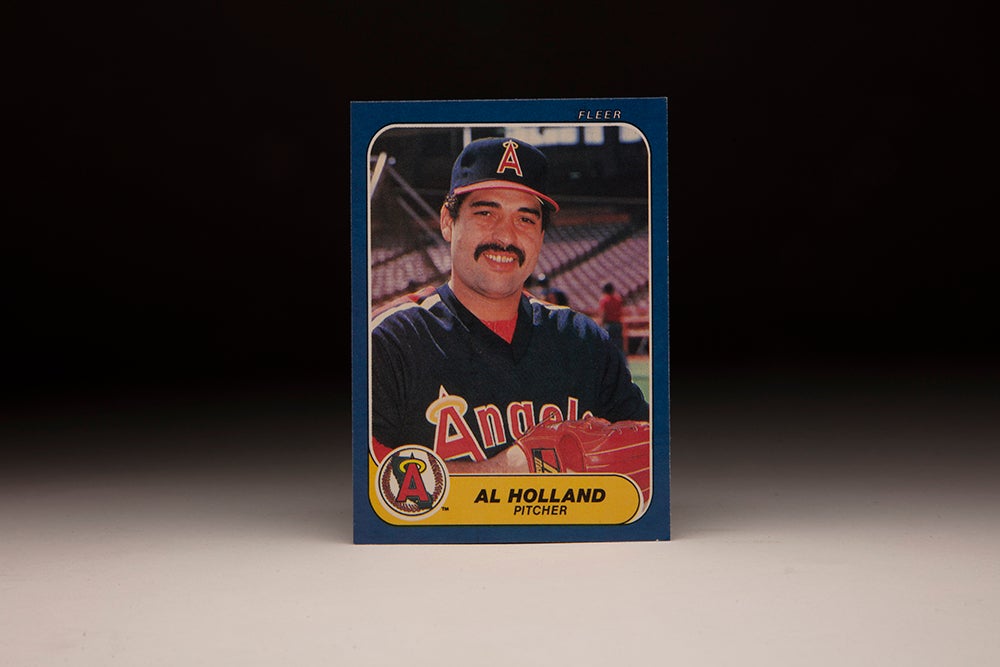

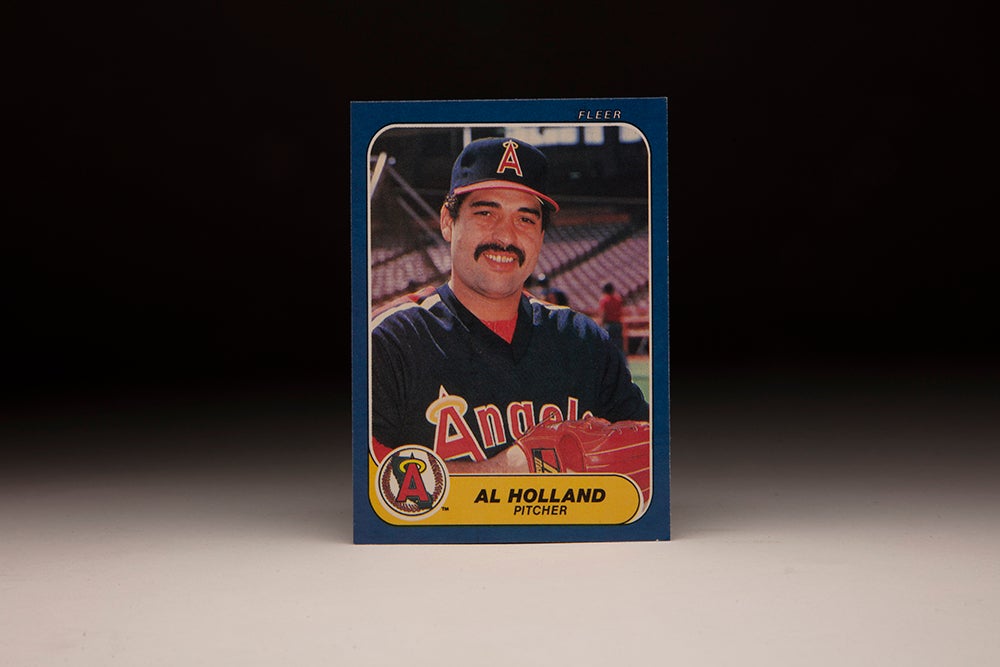

#CardCorner: 1986 Fleer Al Holland

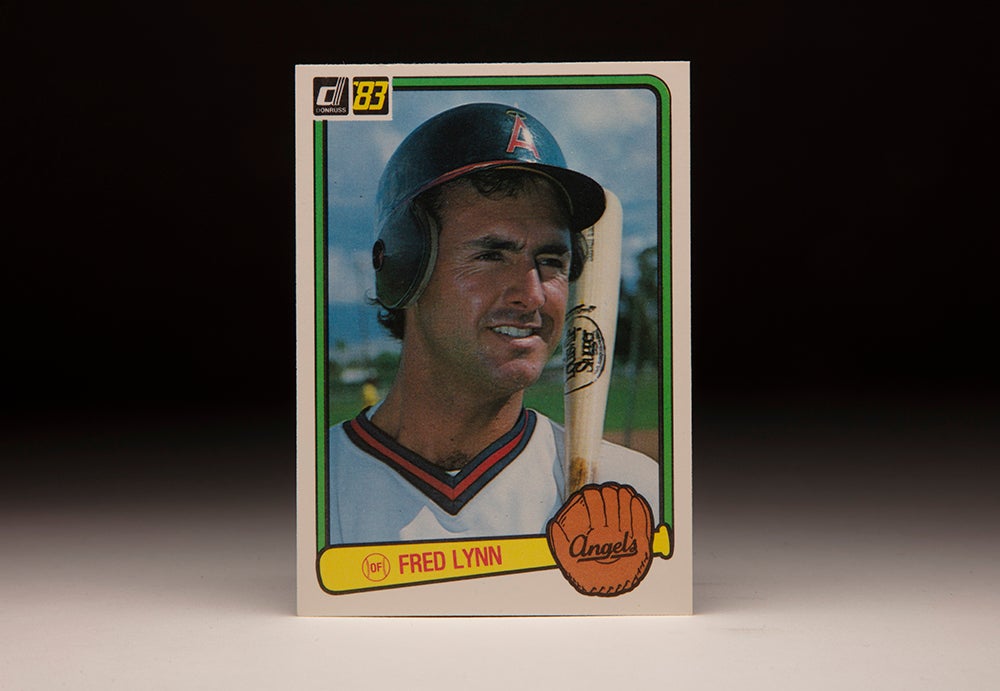

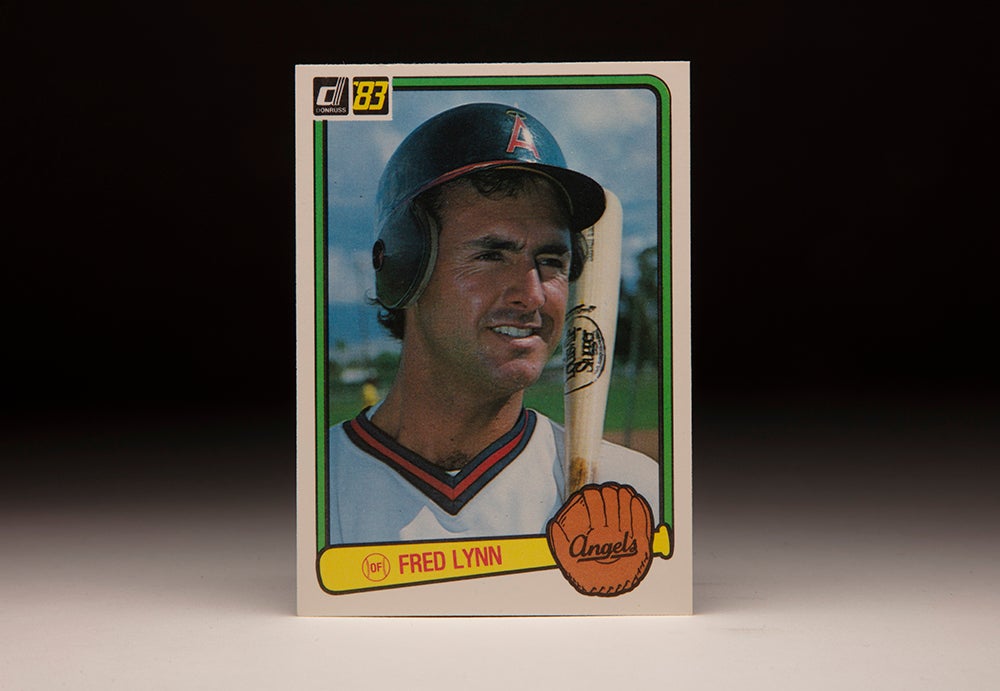

#CardCorner: 1983 Donruss Fred Lynn

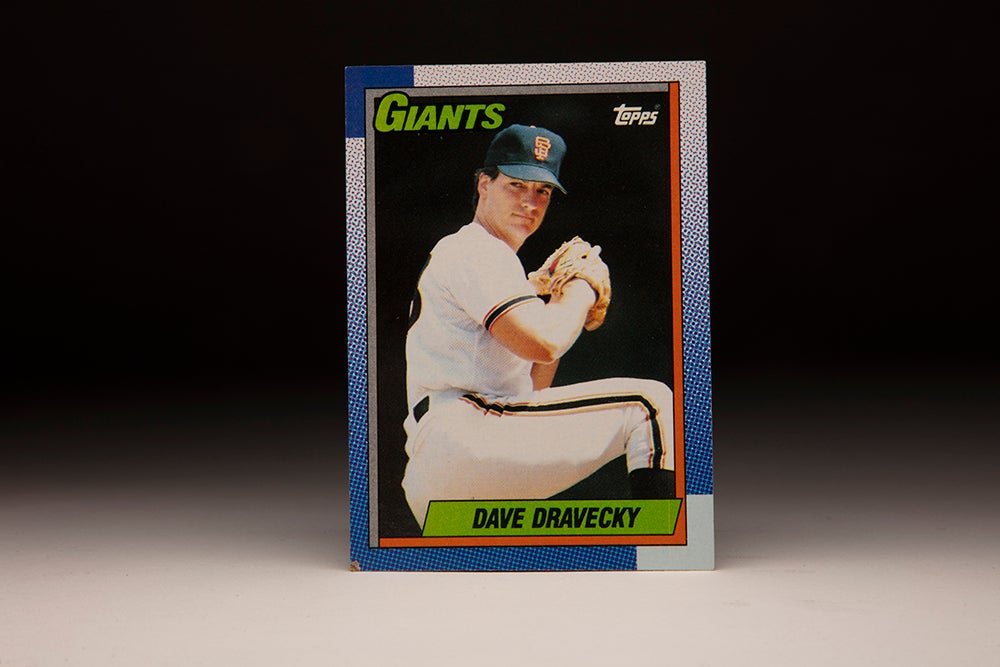

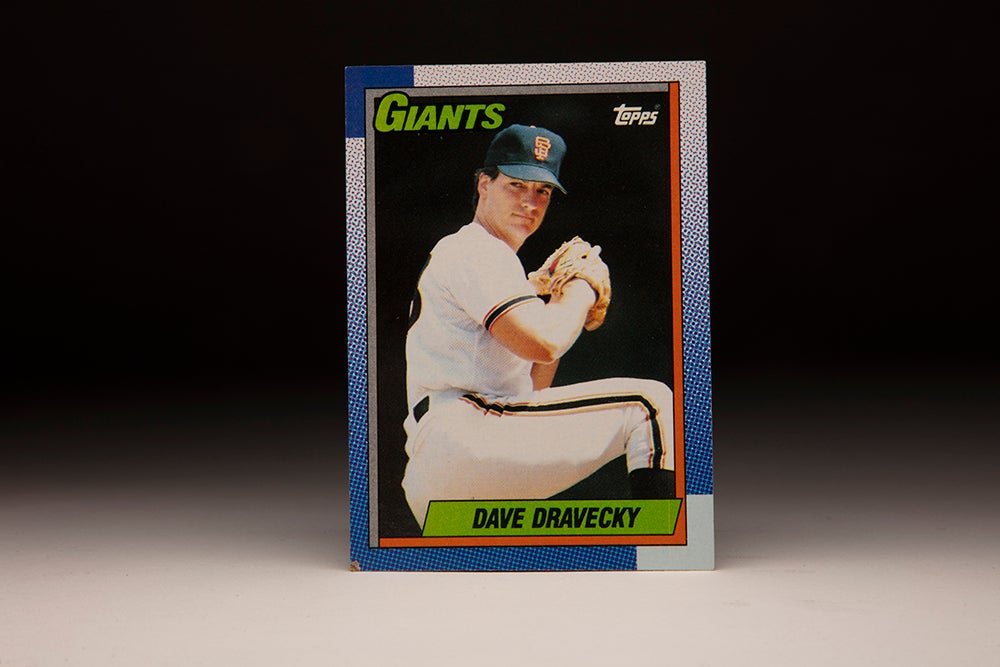

#CardCorner: 1990 Topps Dave Dravecky

#CardCorner: 1976 Topps Ron LeFlore

#CardCorner: 1986 Fleer Al Holland

#CardCorner: 1983 Donruss Fred Lynn

#CardCorner: 1990 Topps Dave Dravecky