- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 2002 Fleer Premium Mariano Rivera

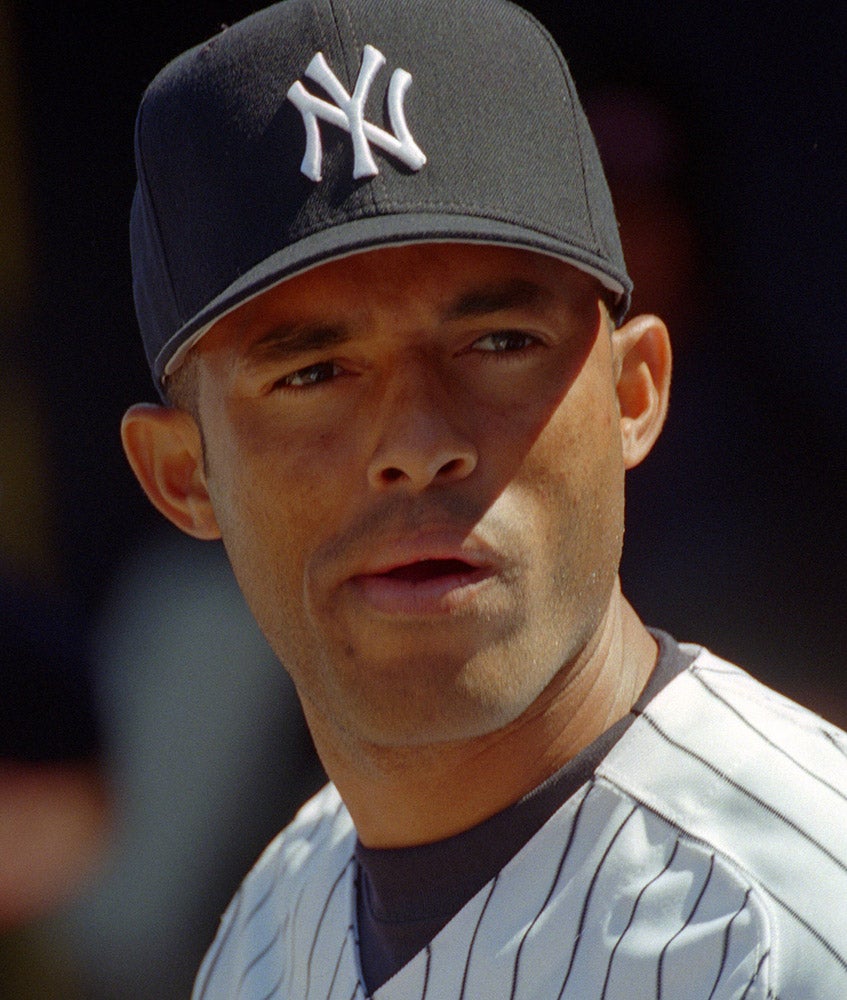

#CardCorner: 2002 Fleer Premium Mariano Rivera

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

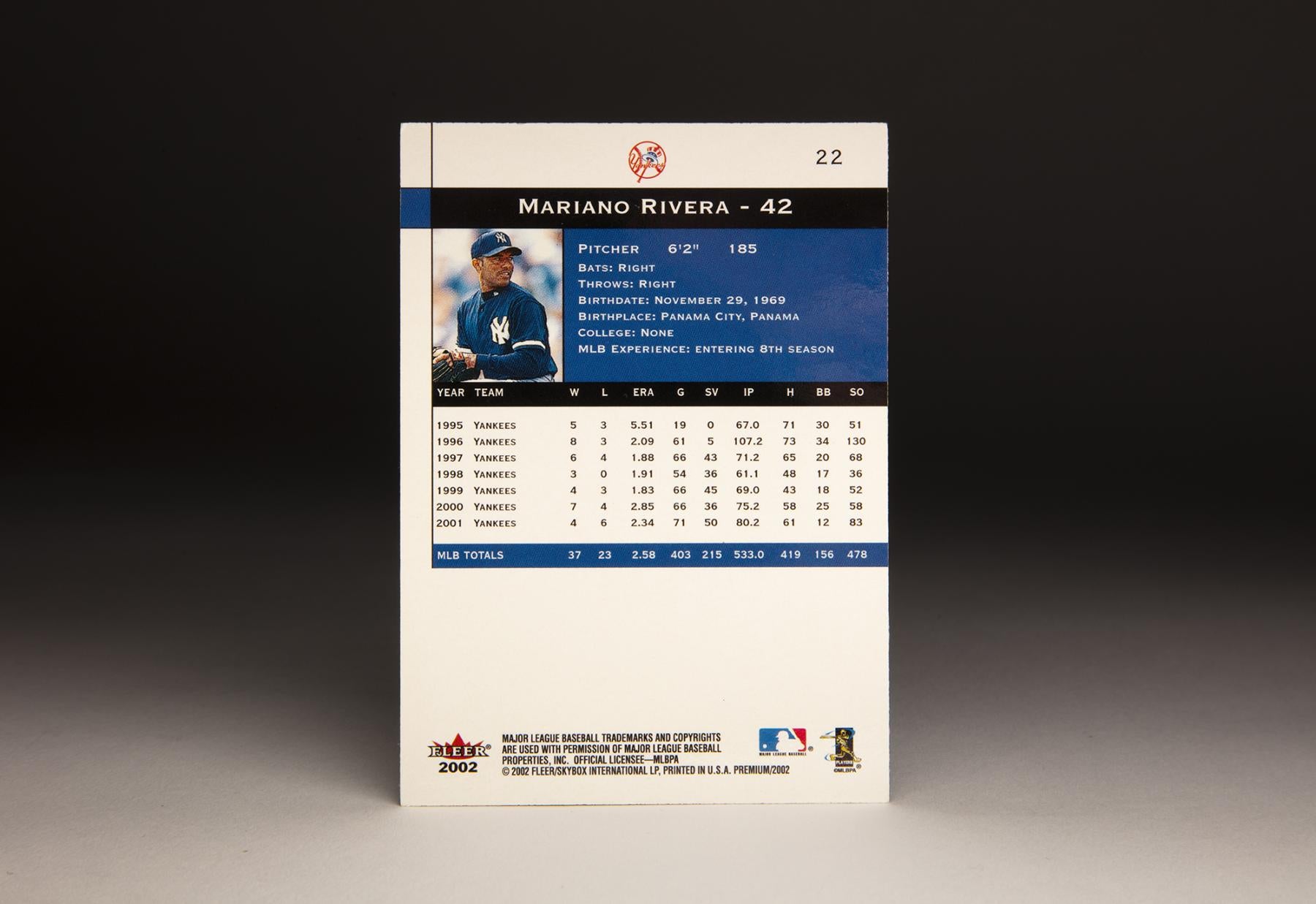

Mariano Rivera, member of a celebrated new class of Hall of Famers, pitched during an era when numerous companies produced baseball cards, and each company seemed to produce a myriad of versions. As a result, there is no shortage of cards depicting Rivera, which makes it difficult to pin down a favorite card.

In particular, I have a fondness for the 1997 and 2001 Rivera cards produced by Topps; they’re both good action shots, and either one could have easily been chosen to occupy this space. Ultimately, though, I chose a Fleer card from the 2002 season. It’s not part of the Fleer base set, but a card from what Fleer categorizes as its “Premium” set.

It seems fitting to select a premium card for a reliever who was often described as the premium reliever of an era that began in the mid-1990s and continued well into the 21st century.

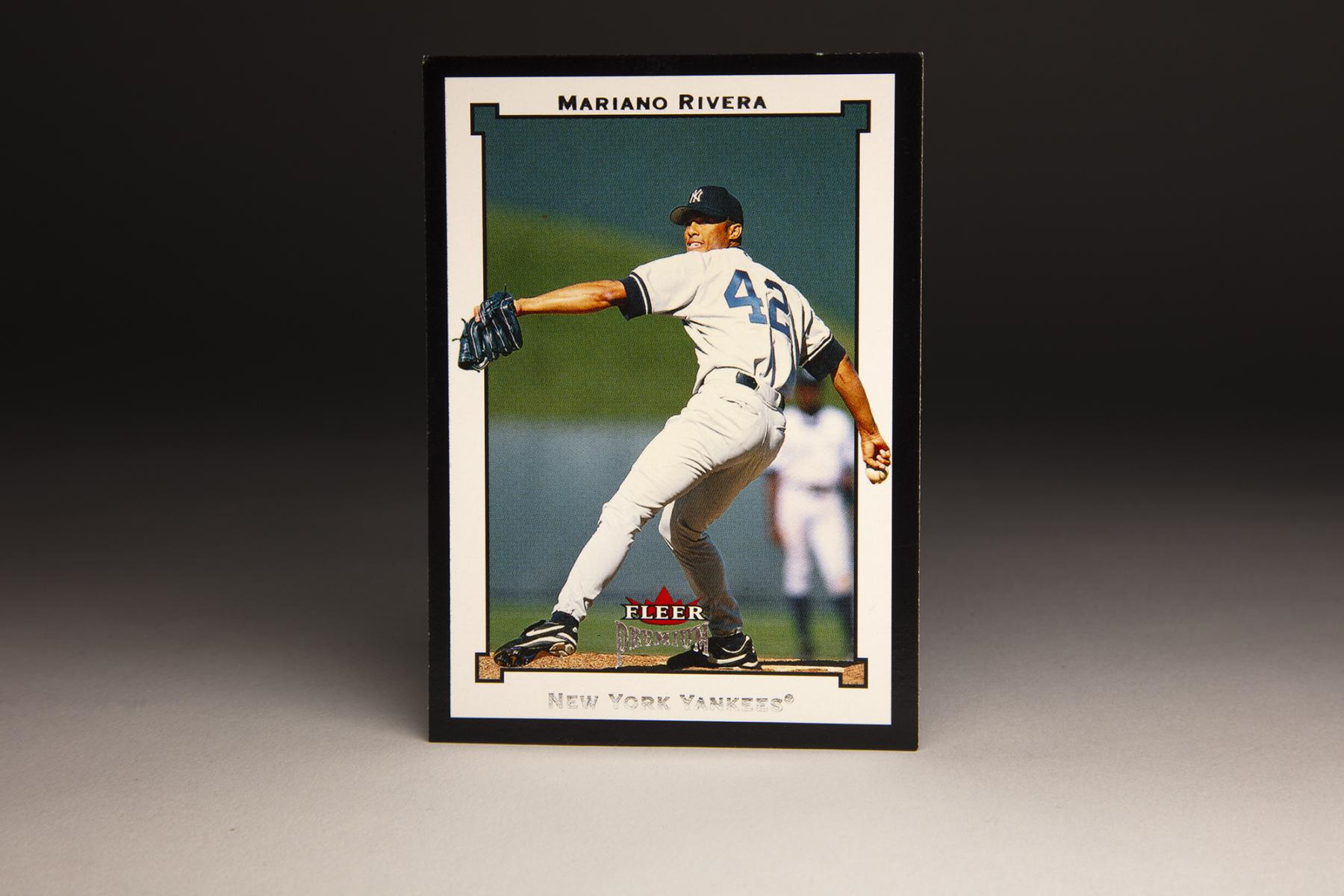

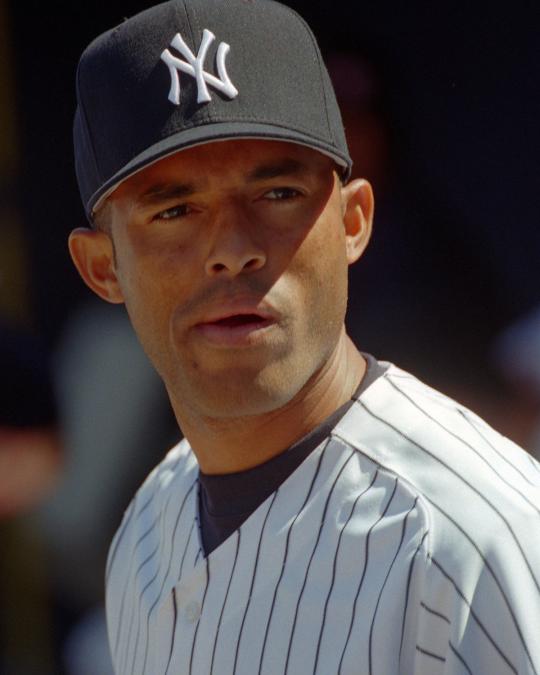

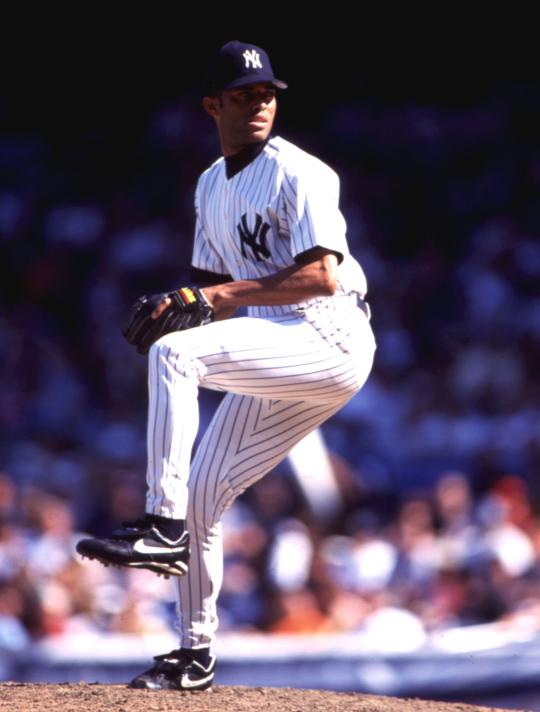

The 2002 Fleer card is a beautiful version of Rivera. First, it captures him in the middle of that smooth, easygoing pitching motion, one in which Rivera seemed to extend little effort or strain while displaying what some have called perfect mechanics. While some pitchers rely on a motion that places an emphasis on hiding the ball from sight and deceiving the hitter, Rivera never did. Of course, he didn’t need to rely on deception in his motion, because of the devastating movement of his trademark cut fastball, along with his pinpoint control and command.

While many of today’s modern day cards are too flashy for my tastes, the Rivera card is just right. It retains the basic white border of the past, while emphasizing the simplest of designs. There are four colored squares, one in each corner of the photographic image, along with the regal logo of “Fleer Premium” stamped near the bottom of the card. And that’s it. There are no extraneous colors or designs, no tendency to extend the photos to the edges of the card and make it look like a postcard, a trap that envelopes many of the 21st century cards.

Yet, as simple as the design is, there is also a neat trick on display here. Notice how Rivera’s glove hand and his pitching hand extend beyond the frame of the card, to the point where they venture into the white space of the border. This creates almost a three-dimensional effect, giving us the impression that Rivera’s figure is popping out of the restraints of the card itself.

And finally, as with many great cards, the Rivera selection gives us ground to ponder and speculate. We know that this photo was taken during a Yankee road game, but what was the exact venue? Based on the grass knoll in the background, I believe it’s Kauffman Stadium in Kansas City.

And what about the middle infielder in the background, standing near the second base bag? The player’s build, skin color and old-fashioned manner of wearing stirrups indicate that it’s not Derek Jeter, but more likely Alfonso Soriano. A check of the Yankees’ roster in 2001, when this photograph was likely taken, shows that Soriano was the team’s primary second baseman that season. Not only that, but Soriano played in 156 games in 2001, the vast majority at second base. Yes, that must be Soriano sharing some space with one of our newest Hall of Famers.

As intriguing as the 2002 Fleer Premium card is, no card can fully embody the brilliance of Rivera’s career. Born in Panama City but raised in the village of Puerto Caimito, Rivera grew up relatively poor. He and his friends could not afford regulation baseball equipment, so they made do with what they had and improvised, constructing gloves out of milk cartons and bats out of tree branches.

In this way, Rivera began to lay the foundation for a career that would eventually yield greatness.

At first, it seemed like baseball would remain a distant dream. After finishing high school, Rivera went to work for his father as a fisherman. While it was honest, hard work, Rivera did not enjoy it, especially the day he found himself on a 120-pound vessel that was sinking into the ocean. His uncle would also die from injuries in a fishing accident, something that had a profound effect on Rivera.

Incidents like those convinced Rivera that fishing was not for him. So he decided to pursue baseball, initially as a member of the Panama Oeste amateur team in 1988. Rivera was not a pitcher at first, but rather an athletic shortstop. One day he volunteered to pitch. Not only did he do well, but he eventually happened to catch the eye of Yankees scout Herb Raybourn, who was on a scouting trip to Panama.

Raybourn had earlier seen Rivera play shortstop, but was convinced that he was not a legitimate middle infield prospect. By now, things had changed. Rivera’s pitching made Raybourn take a second look. Rivera did not throw particularly hard, only about 85 to 87 miles per hour, but Raybourn liked his smooth, effortless delivery.

Based on Raybourn’s recommendation, the Yankees signed Rivera to a contract, including a bonus of $2,500, in 1990. They assigned him to their affiliate in the Gulf Coast League, where he dominated as a reliever. The following year, the Yankees made him a starter; he continued to pitch well, putting up good numbers across the board.

Statistically, Rivera did well, but his relative lack of size (6-foot-2 and 165 pounds) and absence of an overpowering fastball made him a fringe prospect in the minds of most scouts. During the 1992 season, his status as a prospect worsened when he injured the UCL in his right elbow, mandating surgery to replace the ligament. The surgery put him on the shelf for the rest of the season.

After the ’92 season came to an end, the Yankees prepared for the expansion draft, putting together a list of protected players who could not be taken by the two new franchises, the Colorado Rockies and Florida Marlins. Given his injured status, the Yankees did not protect Rivera. He could have been selected by either of the two new clubs, but then again, they had no idea of the potential of the young, raw Rivera.

Still rehabilitating his arm at the beginning of the 1992 season, Rivera returned to action in the Gulf Coast League before earning a midseason promotion to Greensboro, a full-season Class A affiliate of the Yankees. Rivera pitched well that season, but most talent evaluators remained skeptical that he would ever make the major leagues. His repertoire of pitches –a fastball, slider, and very good change-up – were considered too ordinary to succeed at higher levels.

The 1994 season would mark a turning point in Rivera’s career. Beginning the year in the Florida State League, he would move up to Double-A, and then Triple-A before the end of the season.

Although he posted an ERA of 5.81 for Triple-A Columbus in six starts, his rapid ascent through the Yankee system elevated his status from fringe prospect to a ranking as the Yankees’ No. 9 prospect, according to Baseball America.

After starting the 1995 season at Columbus, Rivera earned a call-up to New York in May. When starter Jimmy Key came down with an injury, Yankees manager Buck Showalter moved Rivera into the rotation. Making four starts, Rivera struggled, prompting a return to Columbus and spurring trade rumors. One report had the Yankees considering a deal that would sent Rivera to the Detroit Tigers for veteran left-hander David Wells.

Pitching at Triple-A, Rivera came down with a sore shoulder that sidelined him briefly. When he returned, he was suddenly throwing fastballs in the range of 95 to 96 miles an hour, six miles faster than previous readings. Skeptical of the report, Yankees general manager Gene Michael checked with Columbus officials to see if their radar gun was functioning properly. It was. Michael then discovered that a scout for another team had also registered similar readings on his radar gun. Mysteriously, Rivera had elevated his fastball to that of a power pitcher. That convinced Michael to take Rivera off the trade block.

But initially, Michael had listened to the Tigers and given a deal some consideration. “'I never said yes, and I never said no,” said Michael, according to the book, Champions: The Saga of the 1996 New York Yankees, written by John Harper and Bob Klapisch. “I'm glad I never had to. They thought they could get more than that [Rivera] for Wells. Then when Rivera started throwing 95, it was too late. Nobody was going to get him.”

The Yankees soon brought Rivera back up to New York, but his time in the starting rotation produced mixed results. In September, Showalter moved him to the bullpen. That fall, Rivera pitched scoreless ball over five and a third innings of relief in the American League Division Series, convincing the Yankees that he needed to become a fulltime reliever.

Yet, his Yankee career almost came to an end in the spring of 1996. With Derek Jeter struggling during Spring Training, the Yankees became worried that the lack of an established shortstop would derail their pennant hopes. The Yankees talked to the Seattle Mariners about the availability of veteran shortstop Felix Fermin.

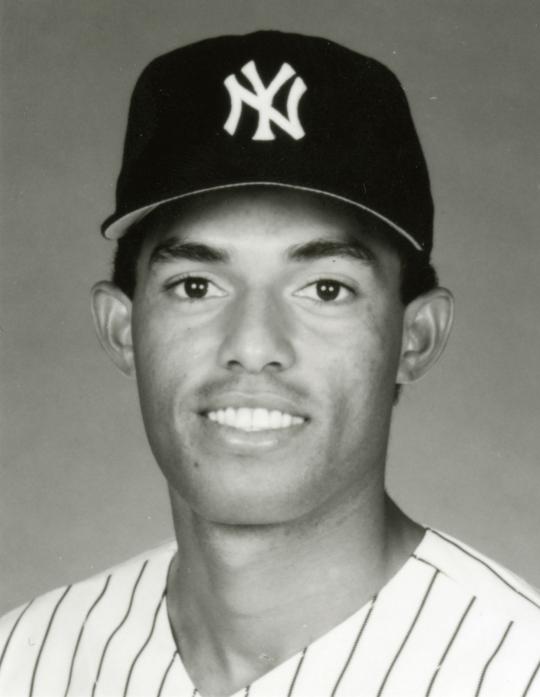

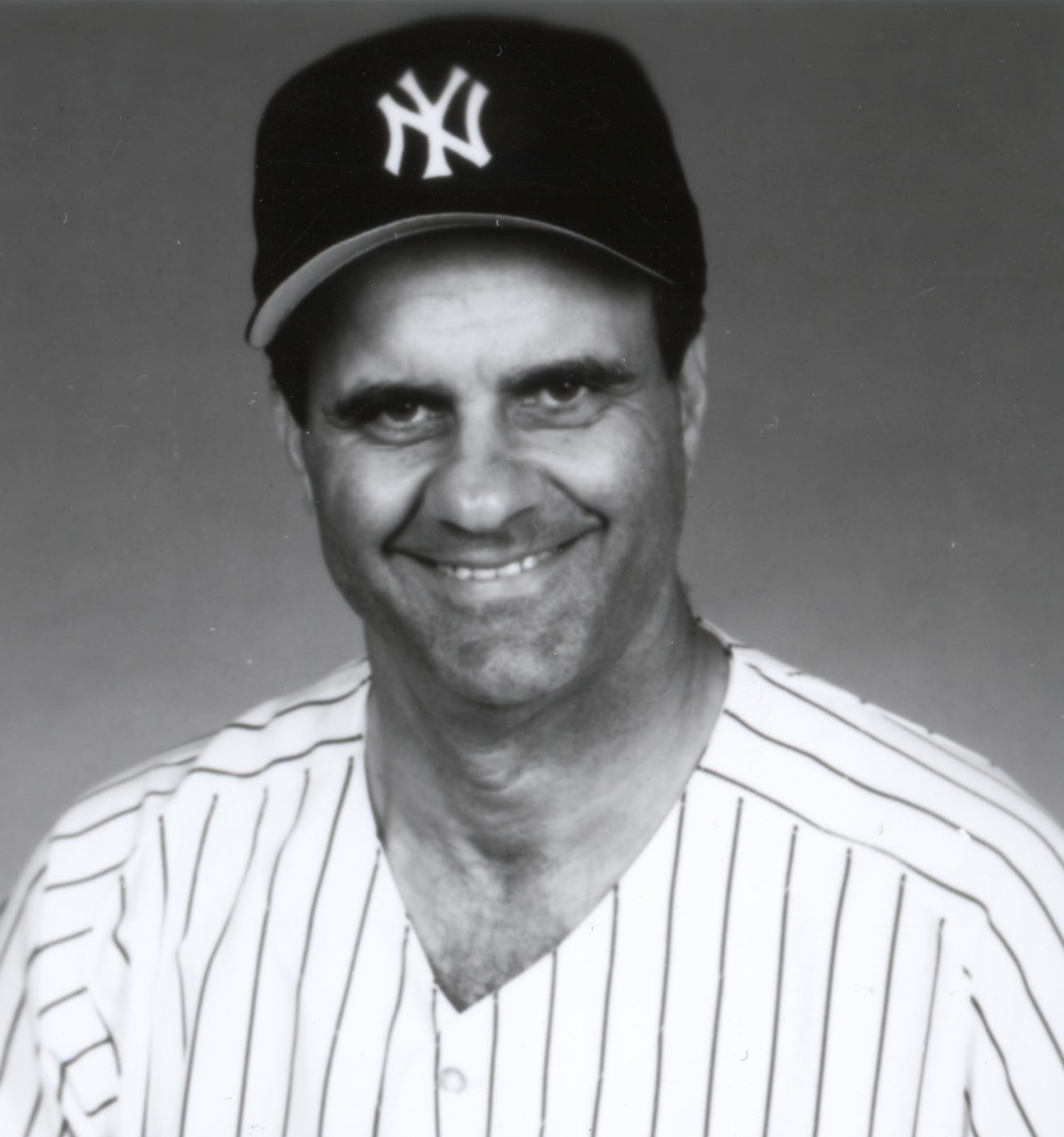

Mariano Rivera was raised in Puerto Caimito, Panama, where he worked for his father as a fisherman after graduating high school. Rivera also pursued baseball, as a member of the Panama Oeste amateur team, and it was there that he caught the eye of Yankees scout Herb Raybourn. (Cliff Welch/National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

A good defensive shortstop, Fermin lacked much of an offensive game and had reached his ceiling as a player. Still, the Mariners asked for Rivera in return. Owner George Steinbrenner wanted to make the trade, but new general manager Bob Watson, new manager Joe Torre, and Michael, now working in an advisory role, talked The Boss out of it.

Rivera made the Opening Day roster, starting the season in a long relief role. He roared in April, posting a 1.25 ERA over 10 appearances. Among them were three outings against Minnesota, in which he blanked the Twins over nine innings. Those appearances left Twins manager Tom Kelly stunned, and hoping to see Rivera move out of the American League. “This Rivera guy, we don’t want to face him anymore,” Kelly told the New York Post. “He needs to go a higher league. I don’t know where that league is. He should be banned from baseball. He should be illegal.”

Given such dominance, Torre turned to Rivera to pitch a more critical role, often using him in the seventh and eighth inning of close games. Becoming the primary set-up man to closer John Wetteland, Rivera emerged as a workhorse – a dominant one at that. Appearing in 61 games, Rivera logged 107 innings. He allowed only 73 hits and pitched to the tune of a 2.09 ERA.

That postseason, Rivera’s run of remarkable pitching continued. He made eight appearances combined in the Division Series, the LCS, and the World Series, not allowing a single run and making himself a huge factor as the Yankees stunned observers by winning their first championship since 1978.

Rivera pitched so brilliantly that the Yankees let Wetteland leave as a free agent at season’s end, thereby allowing the skinny right-hander now known simply as “Mo” to become their closer in 1997. At the start of the season, he struggled, blowing three of his first six save opportunities. And then one day, in June, he and teammate Ramiro Mendoza were throwing to each other on the side, when his fastball offerings started to move so much that Mendoza struggled to catch them. That day, Rivera’s famed cut fastball, or cutter, arrived. He claimed that he had done nothing to change his grip or his arm action; in his words, the cutter was a “gift from God.”

From that point, Rivera began to throw the cutter more and more. (At one time, it was said that he threw cutters 92 percent of the time, an astounding rate). By the end of the season, he had accumulated 43 saves and would garner some MVP Award consideration, even if the postseason did end in disappointment when he gave up a game-tying home to Cleveland’s Sandy Alomar in the eighth inning of Game Five of the ALDS. That momentary setback led to a playoff ouster at the hands of the Indians.

The trauma of coughing up a lead in a key postseason game might have derailed a lesser man. Not Rivera. Over the next three seasons, he pitched superbly, dominating the ninth inning (and occasionally the eighth inning). From 1998 to 2000, when the Yankees won three straight world championship to stake their claim to a dynasty, he earned 117 saves, and posted ERAs of 1.91, 1.83, and 2.85. He was nearly untouchable in 1999, when he led the league with 45 saves, finished third in the Cy Young balloting, and placed 14th in the MVP balloting.

In 2001, Rivera reached a milestone of 50 saves, at the time the best total of his career. He pitched stupendously in the Division Series and the LCS, helping lift the Yankees to their fourth consecutive World Series appearance. In Game 7, with the Yankees having taken a 2-1 lead, Joe Torre called on Rivera to close out the game in the ninth inning. Rivera gave up a leadoff single to Mark Grace and then made a rare mistake, committing a throwing error on Damien Miller’s bunt attempt. Jay Bell then laid down a bunt, which Rivera pounced on. He threw to Scott Brosius to third for the first out, but Brosius failed to make a relay to first base, where he likely would have completed a double play.

Tony Womack followed with a line double to right, tying the game and putting the winning run on third. After hitting Craig Counsell with a pitch, Rivera then watched Luis Gonzalez hit a humpback liner to center field, over the head of a drawn-in Jeter. Just like that, the Yankees had lost the Series, with Rivera taking a crushing defeat, despite allowing only one hard-hit ball in the fateful inning.

Even in defeat, Rivera handled himself well. He stayed in the clubhouse, answering all of the questions from the media. It was the kind of gentlemanly grace that marked Rivera, on and off the field.

Once again, Rivera bounced back from postseason adversity. After a slight falloff in 2002, his pitching reached superhuman levels over the next four seasons. He posted ERAs of 1.91 and below during that stretch, remaining a durable closer who consistently pitched 65 to 70-plus games.

In all four of those seasons, Rivera received consideration for American League MVP, and in three of those seasons, he also received voting support for the Cy Young Award. In 2007, Rivera experienced his worst full season, but his numbers were hardly shameful. His ERA of 3.15, his 30 saves, and his 68 hits allowed in 71 innings would have been good for must human relievers. For the first time since 1998, Rivera did not appear in an All-Star Game or earn a vote for Cy Young or MVP.

The 2008 season marked the start of another great Rivera run. He lowered his ERA to 1.40 and finished an impressive fifth in the Cy Young Award voting. In 2009, his 1.76 ERA and 44 saves highlighted a regular season that spilled over into more postseason success. Pitching against the upstart Philadelphia Phillies in the World Series, Rivera made four appearances, did not allow a single run, and stood on the mound as the Yankees won the fifth world championship of his tenure in New York.

Rivera would never again appear in a World Series, but he remained unflinching in regular season and playoff action. (For his career, he put up a remarkable ERA of 0.70 in the postseason.) He adjusted his pitching style, mixing in more four-seam fastballs to go with his cutter, and the strategy worked to keep hitters off-balance.

In 2010 and ’11, he posted ERAs below 2.00, earned two more All-Star Game nods, and finished eighth in the Cy Young balloting the latter campaign. Then came the abbreviated season of 2012, when Rivera made only nine appearances before his season ended due to a freak injury that resulted in the tear of the ACL in his knee.

During the spring, Rivera had hinted about retiring at the close of the season, but he did not want his career to end on an injury and quickly announced his plan to return. Over the balance of the season and the winter, Rivera rehabilitated the knee and made his way to Spring Training in Tampa, Fla. On March 13, only a few weeks after Spring Training had begun, Rivera announced that the 2013 season would mark his last.

Roaring to a fast start, Rivera maintained the pace throughout the summer. By season’s end, he had compiled typical Rivera numbers: a 2.11 ERA over 64 appearances, only 9 walks in 64 innings, and 44 saves. Even at 43 years old, Rivera had shown virtually no slippage in his performance.

Remaining lean and lithe, he seemed capable of going on for years, but a desire to spend more time at his home with his family dictated that the time was right to leave the game. When Rivera retired, the countdown began to his first appearance on a Hall of Fame ballot, in 2019.

There was little doubt that he would win election; the suspension lay in whether he would receive 100 percent of the vote, something that had never been done before in Hall of Fame election history. We found out the answer Jan. 22, when the baseball writers came to unanimous agreement on Rivera’s candidacy. 100 percent of the vote. A perfect vote.

For a pitcher who seemed nearly perfect for most of his career, that seems just about right.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

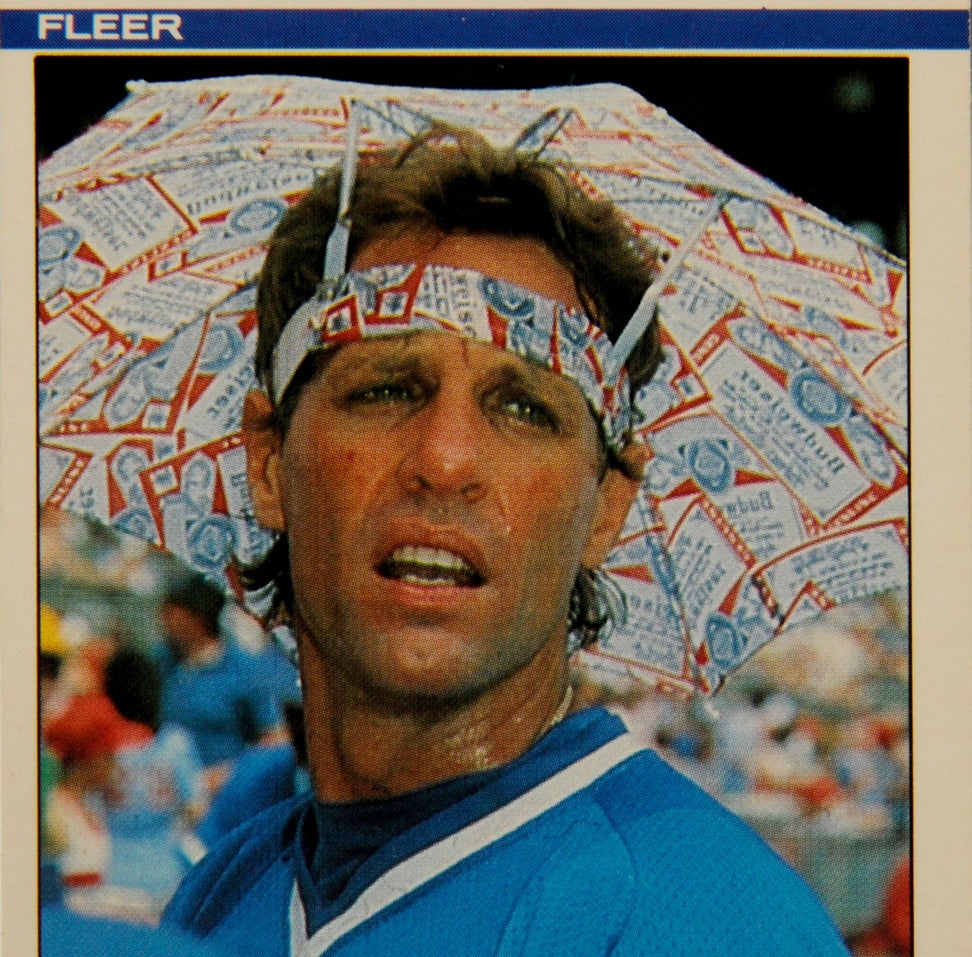

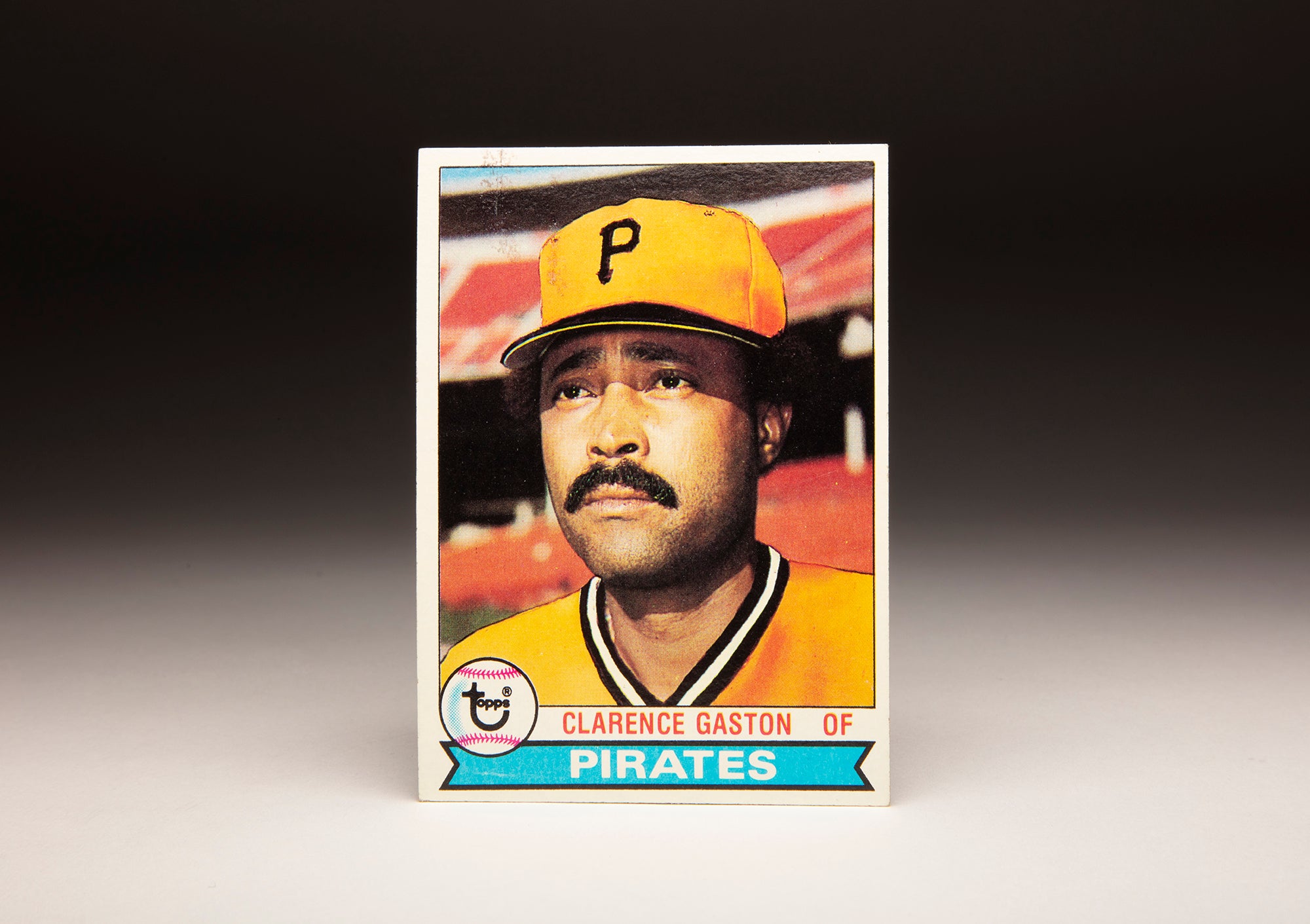

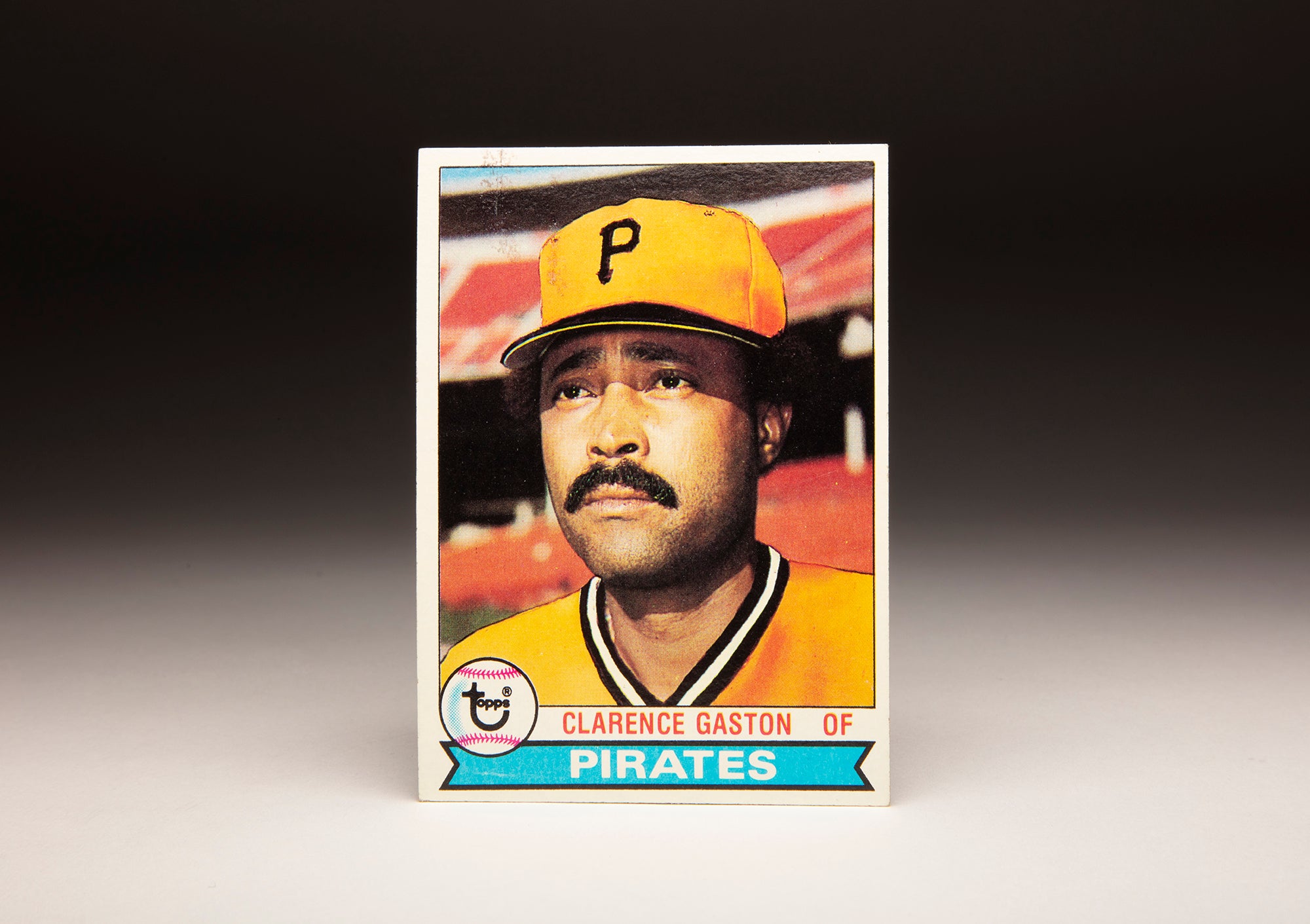

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Clarence Gaston

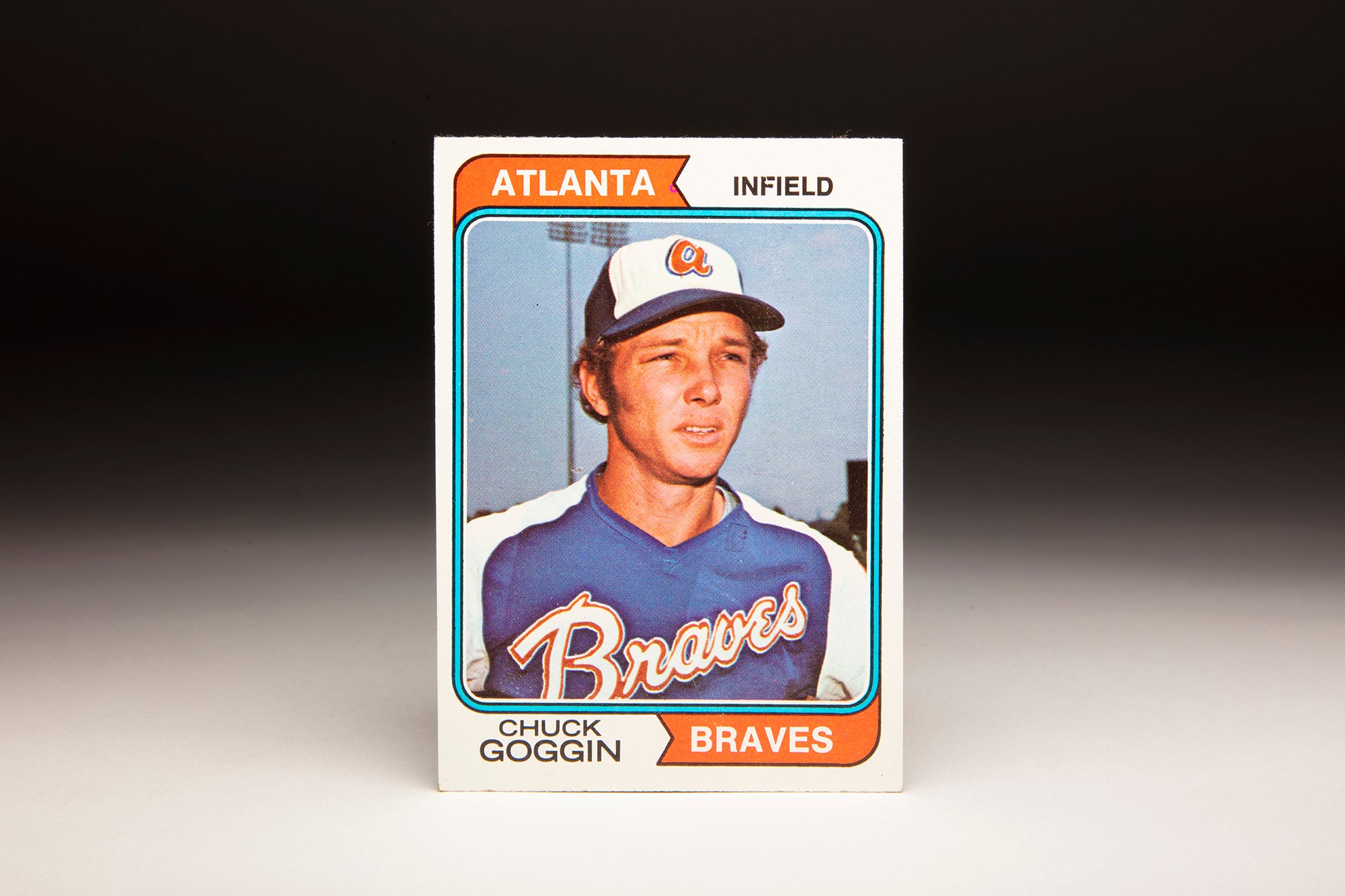

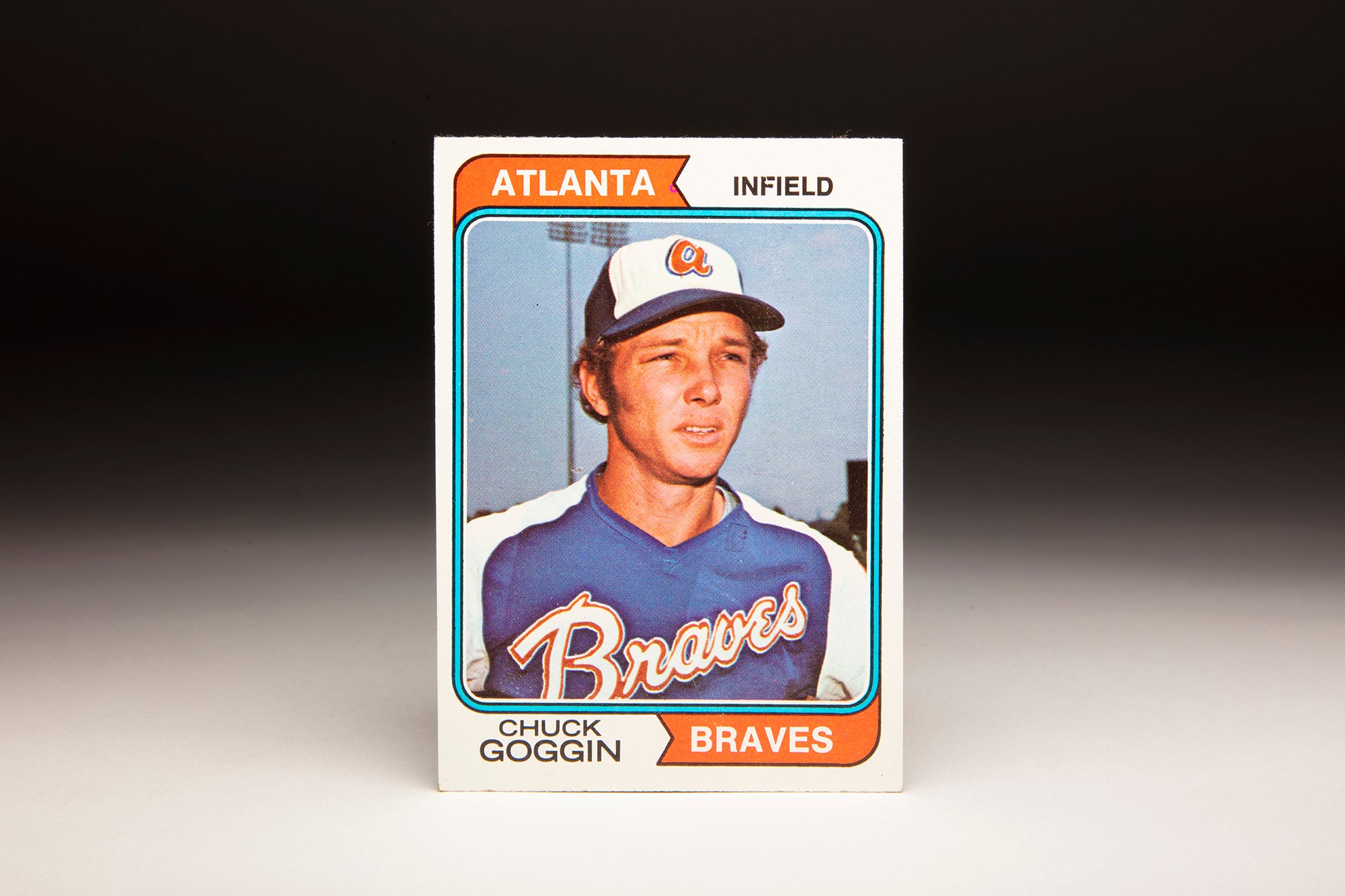

#CardCorner: 1974 Topps Chuck Goggin

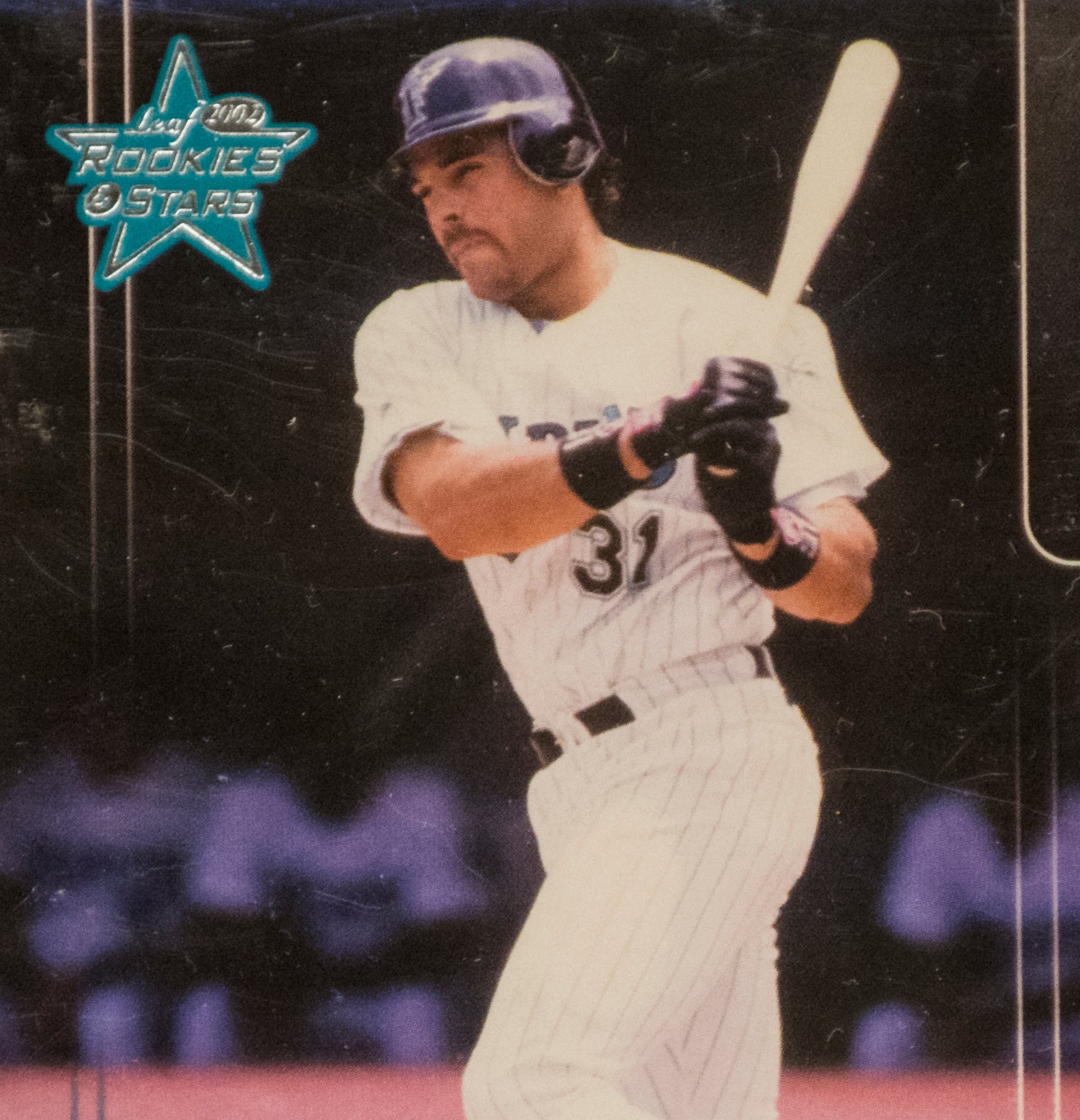

#CardCorner: 2002 Leaf Mike Piazza

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Clarence Gaston

#CardCorner: 1974 Topps Chuck Goggin