- Home

- Our Stories

- McGriff’s 1994 All-Star Game homer was height of season

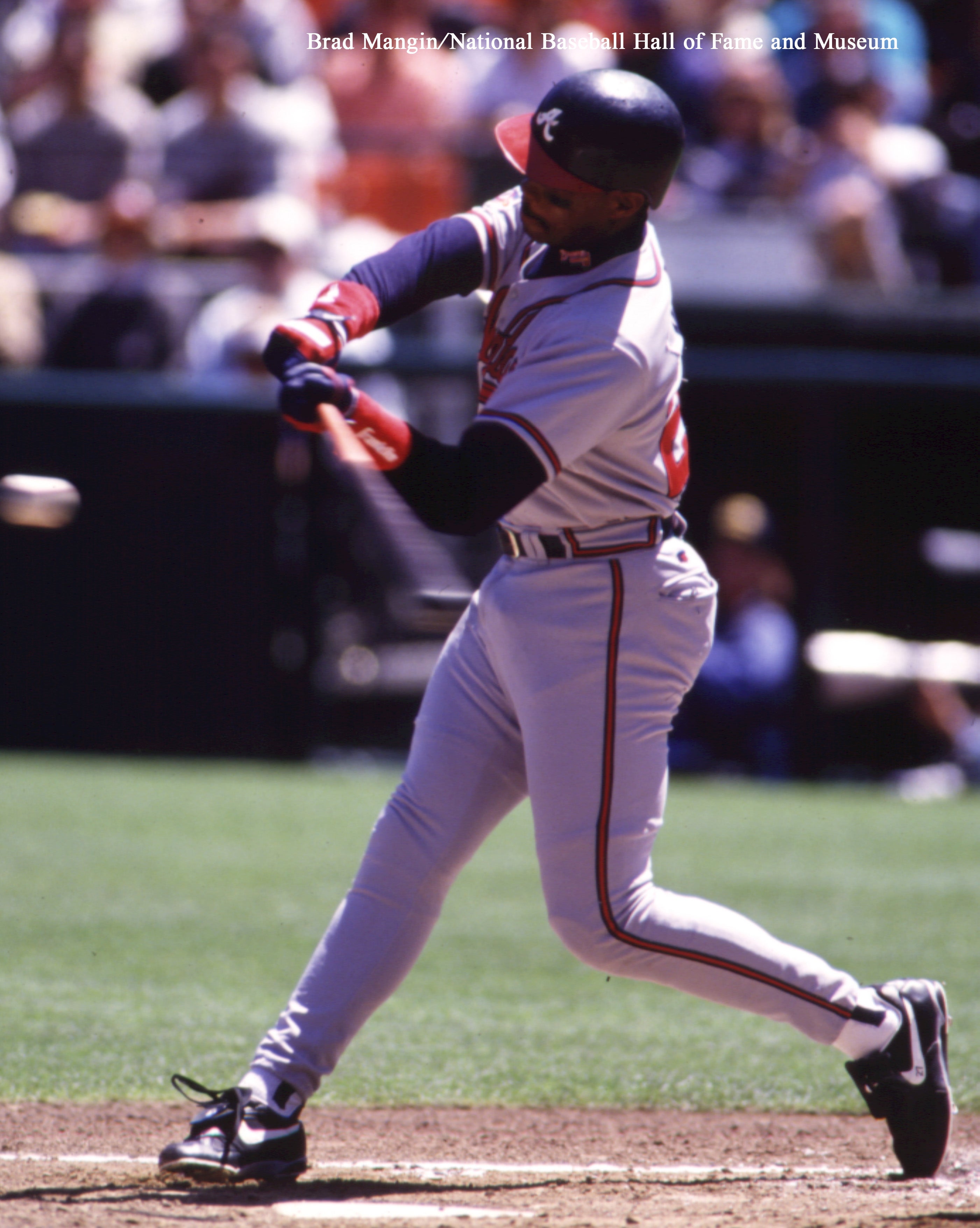

McGriff’s 1994 All-Star Game homer was height of season

A month after the 1994 All-Star Game, a work stoppage wiped away the rest of that season, putting it forever into baseball’s “what if” world.

But on the night of July 12 at Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh, Fred McGriff launched a home run for the ages.

His game-tying two-run shot in the ninth — “She’s gone!” bellowed broadcaster Bob Costas — set up an extra-innings win for the National League, snapping a six-year streak of American League dominance.

It may have been the high point of a summer that seemed headed for one of the great Octobers of all time.

Braves Gear

Represent the all-time greats and know your purchase plays a part in preserving baseball history.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Nearly 30 years later, it was still vivid in McGriff’s mind when he ran into the closer who surrendered that long-ball — Lee Smith — in the halls of the Marriott Marquis in San Diego.

“You can laugh about it now,” McGriff recalled. “Well, he can laugh about it.”

The two were at Baseball’s Winter Meetings this past December, both Hall of Famers now. Smith had just turned 65 the day before. He celebrated his birthday on the same day that McGriff was elected to the Hall.

All 16 members of the Contemporary Baseball Era Players Committee voted for McGriff, who retired seven home runs shy of the 500 career benchmark, after he’d spent 10 years on the writers’ ballot. The emphasis was no longer on the home runs he didn’t hit, but the ones he did.

“He congratulated me on the Hall of Fame,” said McGriff, now 59, of Smith. “And he said, ‘Yeah, you got me.’ I said, ‘Yeah, man. You gotta do what you gotta do.’”

It was a bit of a struggle to know what to say, even after all those years.

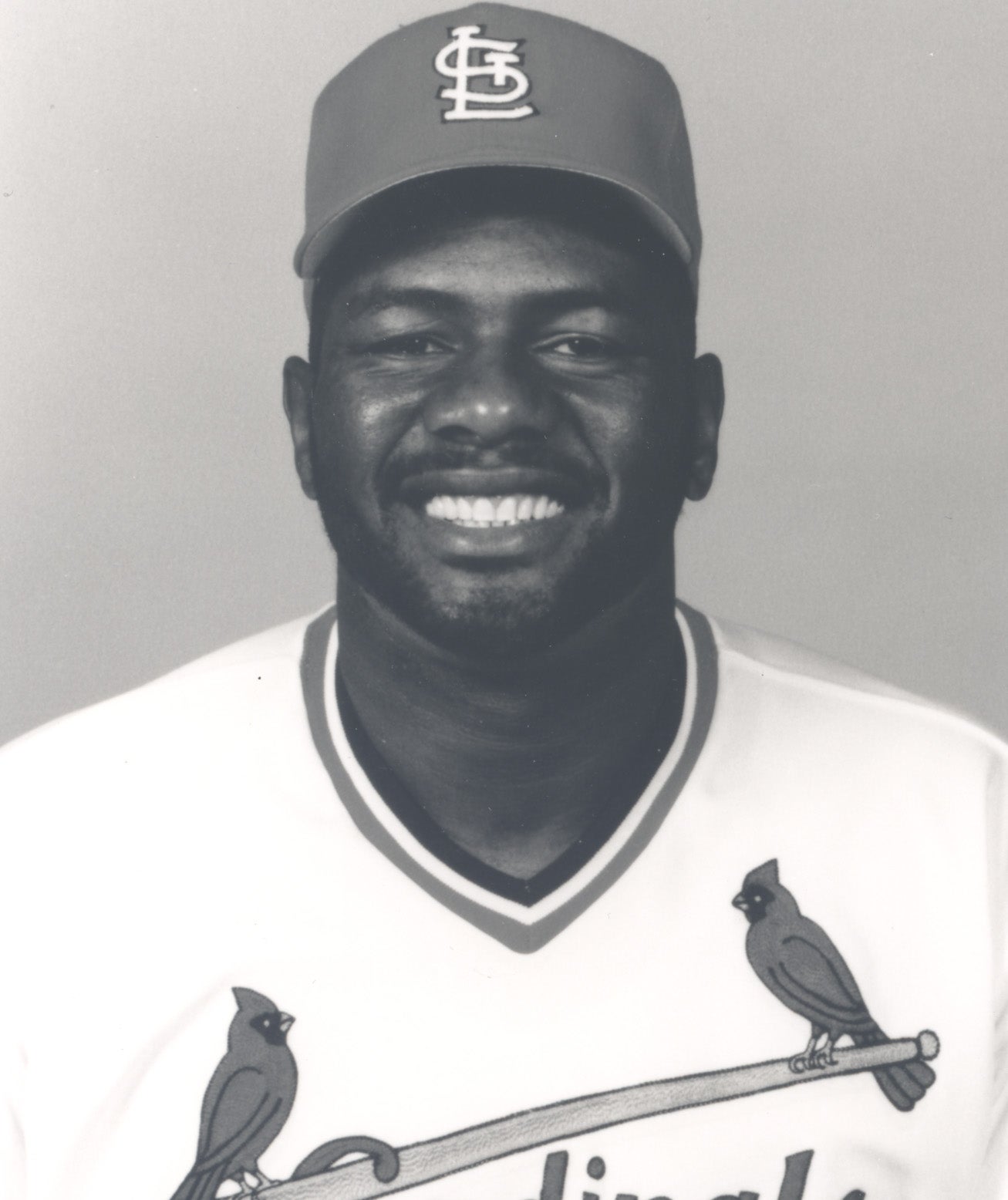

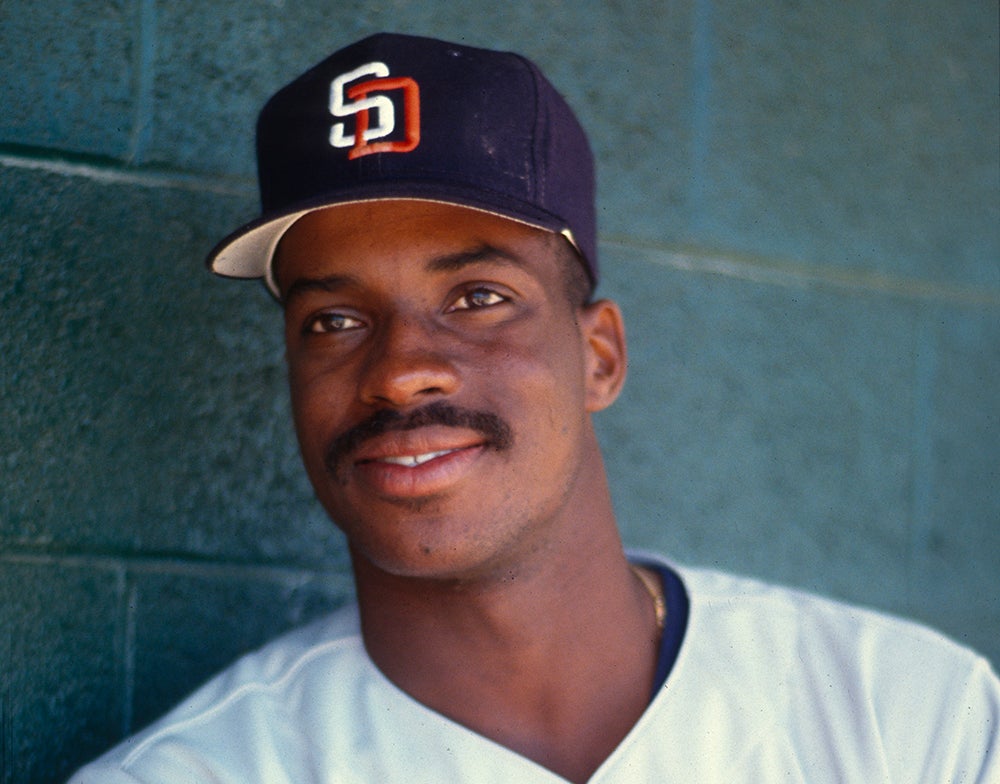

In 1994, McGriff was 30 and playing in his second All-Star Game. He’d started at first base two years earlier in the All-Star Game in San Diego, but this time was a reserve. (St. Louis Cardinals first baseman Gregg Jefferies was voted as the starter.)

Eager to find ways to make the best use of his time, McGriff competed in the Home Run Derby and came up just two homers shy of Ken Griffey Jr., 7 to 5, taking second place.

“It was a fun thing to do,” McGriff said. “It’s also a lot of pressure. You’ve got 40,000 to 50,000 people watching you take batting practice.”

He wasn’t one to spend those two days around the game’s elite, gawking at his fellow All-Stars, especially as a veteran of eight major league seasons by then, but he did like to ask pitchers to sign balls for him. Pitchers? It was all part of his strategy to disarm the men he would stare down for the rest of the season.

“I tried to use the All-Star Game as an advantage for me,” McGriff said. “I got a chance to talk to these same pitchers that I got to face during the regular season. Now I’m in the same locker room with them.

“I’m thinking, ‘Oh, this pitcher has been getting me out. OK, let me go and get him

to sign this baseball.’ And then you say, ‘Oh, man, you’ve got great stuff. Your pitches, that curve you throw, that’s awesome. Can you sign this ball for me?’

“Intimidation and fear is a big part of baseball. So being able to talk to the opposing pitchers is cool.”

During the actual game, though, McGriff started to get restless. He was used to playing. During the course of his 19-year career, he pinch hit just 62 times. By the fifth or sixth inning that night, he was starting to get miffed at NL manager Jim Fregosi, who wanted to hang on to his left-handed ace in the hole.

“I’m sitting there thinking I could have been doing a lot of things,” McGriff said. “I had three days off. I could have been vacationing somewhere.”

The American League scored three runs in both the sixth and seventh innings to lead, 7-5, going into the ninth. AL manager Cito Gaston brought on Smith, who was with the Orioles at the time and had an MLB-best 29 saves, to pitch the ninth.

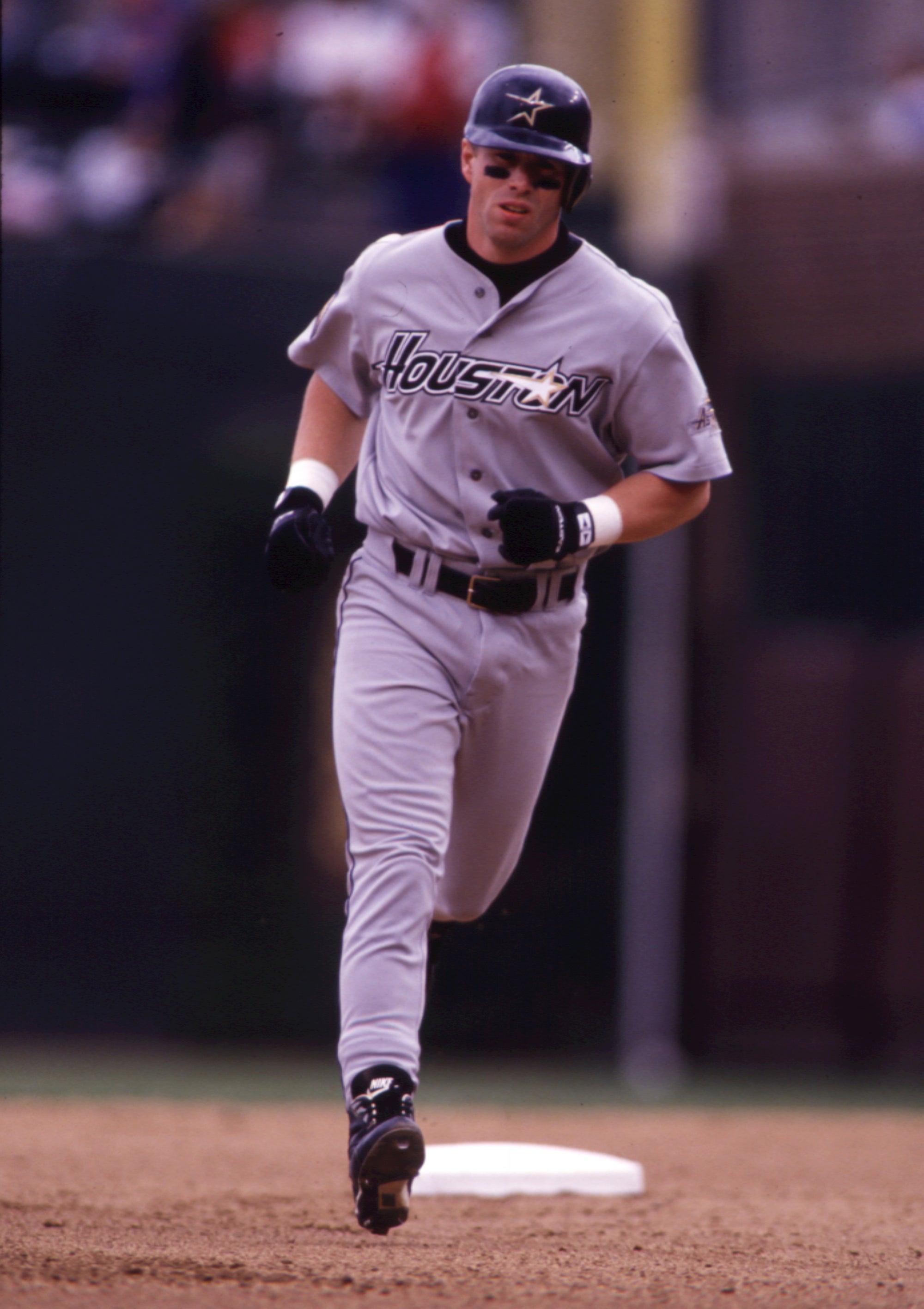

He walked Marquis Grissom. Craig Biggio then grounded sharply to third base — where Scott Cooper double-clutched on his throw to second. Grissom was out there, but the hesitation was just enough to allow a hustling Biggio to reach first base. That’s when Fregosi sent McGriff up to bat for pitcher Randy Myers.

McGriff had gone 1-for-6 in his career against Smith, including a pair of strikeouts when he was with Toronto and Smith with Boston. But he had doubled to score a run off Smith in 1992 when McGriff was a Padre and Smith played for the Cardinals.

“Lee was a tough, very tough pitcher,” McGriff said. “He threw a lot of strikes and was always around the plate. I’d been sitting on the bench for eight innings and was a little stiff, but I’d been going down in the tunnel to take some swings. I told myself, ‘Be aggressive.’”

McGriff fouled off the first pitch. He swung through the second. Down 0-2, he took a ball outside. Then he fouled off another strike.

Gaston had been watching McGriff launch home runs as far back as rookie ball, when McGriff was a Yankees minor leaguer and Gaston was coaching in the Atlanta Braves system. He’d once called Hank Aaron, then the Braves’ farm director, to tell him about a kid named McGriff the team should try to get if they ever had the opportunity.

In 1986, Gaston was the hitting coach in Toronto when McGriff broke into the major leagues there, and he took over as Blue Jays manager when McGriff was in his second year of hitting 30-or-more homers in seven consecutive seasons.

“I wanted to go out and tell Lee Smith not to give Freddy anything to hit, not to give him a fastball out over the plate,” Gaston recalled. “And I said, ‘Ah, Lee probably knows, and he’s probably going to throw him the splitter.’ But no, he threw a fastball out over the plate.”

McGriff got his arms extended on it.

“The ball is skied to left-center field,” Costas relayed from the TV booth. “Lofton goes back. Lofton to the fence….”

As center fielder Kenny Lofton reached the fence, the ball disappeared over the wall and 59,568 fans at Three Rivers roared. McGriff stoically trotted the bases as Smith muttered “Damn,” before beckoning for another ball from catcher Iván Rodríguez. Gaston turned toward Chicago White Sox manager Gene Lamont, sitting beside him as a coach in the visitors’ dugout.

“I’ve always said Freddy and John Olerud are two big guys who really had good eyes out there,” Gaston said. “They didn’t swing at too many bad pitches, and they did hit strikes. That’s why he was so successful.”

McGriff’s game-tying shot sent the game to extra innings. In the 10th, Tony Gwynn led off with a single to center and Moises Alou doubled him in for an 8-7 walk-off win. McGriff was named the game’s MVP.

As McGriff flew to Atlanta to rejoin the Braves, the MVP trophy was shipped to his hometown of Tampa, Fla., to be displayed in the new house he was building. The pyramid-shaped trophy with a glass base and topped with a baseball was one of the few tangible remembrances of that 1994 season.

McGriff was hitting a career-high .318 when baseball halted for the strike. His 34 home runs at the time were three shy of his career high — with 48 games still to play.

“I was having my best year ever,” McGriff said. “And we went on strike.”

All of that potential represented just a slice of what baseball lost in the final two months of that season.

Gwynn was hitting .394 and in the hunt to become baseball’s first .400 hitter since Ted Williams in 1941. Matt Williams (43), Griffey Jr. (40), Jeff Bagwell (39) and Frank Thomas (38) were all aiming for Roger Maris’ single-season record of 61 home runs.

Greg Maddux possessed a 1.56 ERA, the second-lowest since Bob Gibson’s 1.12 ERA in 1968. (Dwight Gooden had a 1.53 ERA in 1985.) And on Aug. 11, when Randy Johnson recorded the last out for Seattle at 9:45 p.m. Pacific time before baseball shut down, it marked his 204th strikeout of the season.

“Baseball was rolling,” McGriff said.

The Montreal Expos had the best record at 74-40, better than both the New York Yankees and division rival Atlanta. They were six games up in the National League East and in ideal position to make the playoffs.

“We shared the same Spring Training complex with the Expos, and they had no fear of playing against us,” McGriff said. “That would have been very interesting.”

Instead, the Braves got a mulligan and a chance to extend their unprecedented run of what would be 14 straight division titles in 1995. The strike proved the beginning of the end for baseball in Montreal, and within 10 years, the Expos had been bought by the major league owners, sold again and relocated to Washington, D.C.

And what might have been in 1994 ultimately had to take a backseat to a singular moment to remember for McGriff and his All-Star teammates.

“To perform and hit a home run against the best of the best is always special,” McGriff said. “It’s one I’ll never forget.”

Carroll Rogers Walton covered the Braves for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and is currently a freelance writer based in Charlotte.

Related Stories

Fred McGriff unanimously elected to Hall of Fame

Exuberant McGriff meets the media as Hall of Famer

McGriff honored, thrilled with Hall of Fame election

McGriff joins new teammates during Hall tour

Bagwell named NL MVP after strike-shortened season

Related Stories

King John Schuerholz

Class of 2016 recalls their fathers’ influence

Baseball Writers’ Association of America 2016 Hall of Fame Ballot Announced

Treasures from Cooperstown Coming to Capital Region for Tri-City ValleyCats Game on Wednesday

MVP campaign leads Reds to extend Larkin

Trade to Houston a boost for Bagwell

McGriff, Rolen anticipating induction day

2015 HALL OF FAME BALLOT OUT TODAY

Celebrate Hall of Fame Weekend Journey Through Inductee Memories at Legends Roundtable Event

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Pagliarulo

Cap Selections Announced for Craig Biggio, Pedro Martinez and John Smoltz

01.01.2023

Curtain Rises on Hall of Fame Weekend as Ozzie Smith and Friends Return to PLAY Ball

01.01.2023