- Home

- Our Stories

- Bud Fowler’s life blazed a trail from Cooperstown

Bud Fowler’s life blazed a trail from Cooperstown

Jackie Robinson may have been the first Black player in the American or National League, but the first Black man to play professional baseball predated Robinson by more than 60 years.

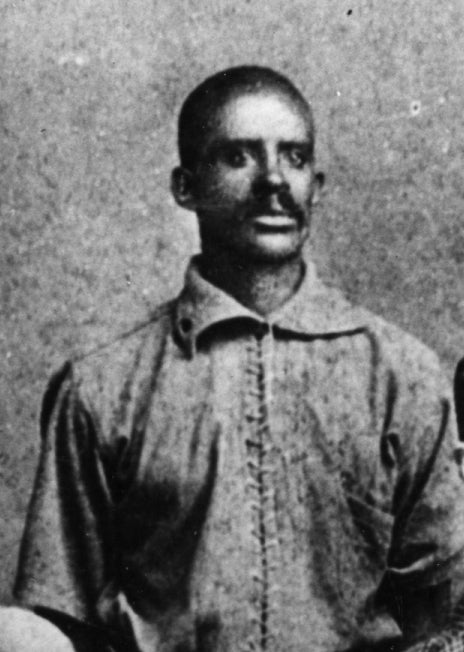

John W. Jackson Jr., better known as “Bud Fowler,” made his pro debut in 1878 in the International Association. He is believed to be the first Black player to play pro baseball.

Born John W. Jackson Jr. in Fort Plain, N.Y., on March 16, 1858, Fowler’s family moved to Cooperstown – located about a half hour from Fort Plain – just a few short years later. According to village historian Hugh MacDougall, just 28 Blacks lived in Cooperstown at that time, and Fowler attended school primarily alongside white children. His father was a barber and in later years Fowler followed in his footsteps to help supplement his income.

In his early years as a pro, Fowler played primarily for a team in Lynn, Mass., but was often called in to pitch as a substitute on other teams. Racism ran rampant, though baseball’s color line had yet to be officially established, and this further fueled Fowler’s transient team affiliations. His time with the Guelph (Ontario) Maple Leafs, for instance, was short-lived because, per the Guelph Herald, “Some of the Maple Leafs are ill-natured enough to object to [a] colored pitcher.”

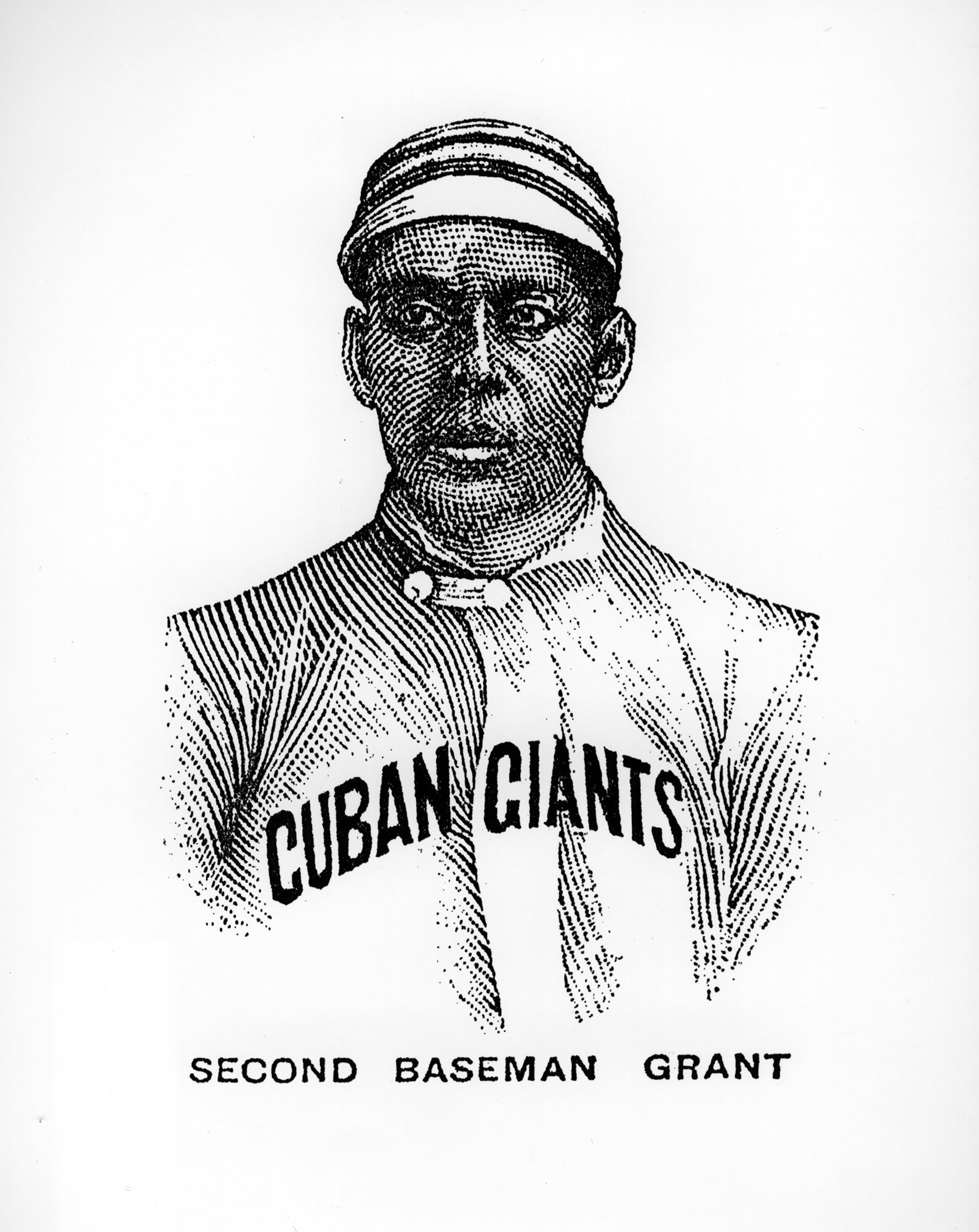

He faced similar obstacles in Binghamton, where the Wilkes-Barre Times Leader reported that “The players of the Binghamton Baseball club were yesterday fined $50 each by the directors because six weeks ago they refused to go on the field unless Fowler, the colored second baseman, was removed.”

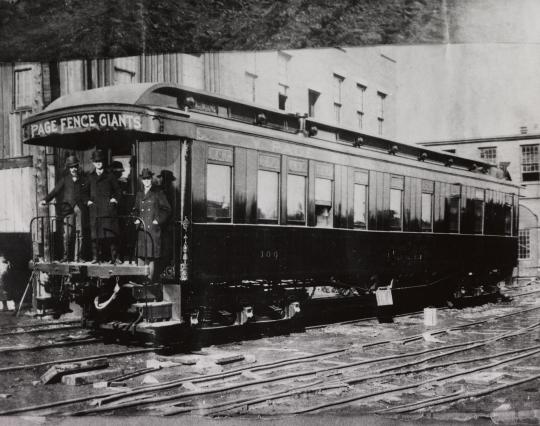

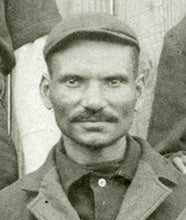

Black baseball pioneer Bud Fowler played for – among other teams – the Page Fence Giants, a top pre-Negro Leagues team of the 19th century that also featured future Hall of Famer Sol White. The team traveled by train in a car that advertised the team. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

The color of Fowler’s skin forced him into a more nomadic career than his white contemporaries. He manned second base for the Keokuk Hawkeyes in Iowa, appeared in the Colorado League, signed with the Topeka Capitals, returned east to star for the Binghamton Crickets, ventured to Indiana to play for the Terre Haute Hoosiers, traveled Southwest to join the New Mexico League, represented Greenville in the Michigan State League and led the Nebraska State League in steals. All told, historians estimate he played for more than a dozen leagues throughout the course of his career, while Fowler himself claimed to have played on teams “based in twenty-two different states and in Canada.”

Despite the lack of consistent playing time, Fowler played professionally for nearly two decades and his talents earned him recognition in the baseball community. “For 16 years he was a pitcher and for 12 years a second baseman, and he never wore a glove, taking everything that came his way with bare hands. He was considered the equal of any man who ever covered the position,” wrote the Berkshire Eagle in 1909.

As baseball’s color barrier grew increasingly explicit, Fowler’s career shifted from playing to organizing. “My skin is against me,” he wrote in 1895. “The race prejudice is so strong that my Black skin barred me.”

Cooperstown High School baseball team members wore “Fowler” nameplates on their jerseys during the 2013 season in honor of Bud Fowler, who grew up in Cooperstown and later became one of the earliest Black professional baseball players. The players dressed in uniform as the Village of Cooperstown dedicated “Fowler Way” on April 20, 2013. (Milo Stewart Jr./National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum).

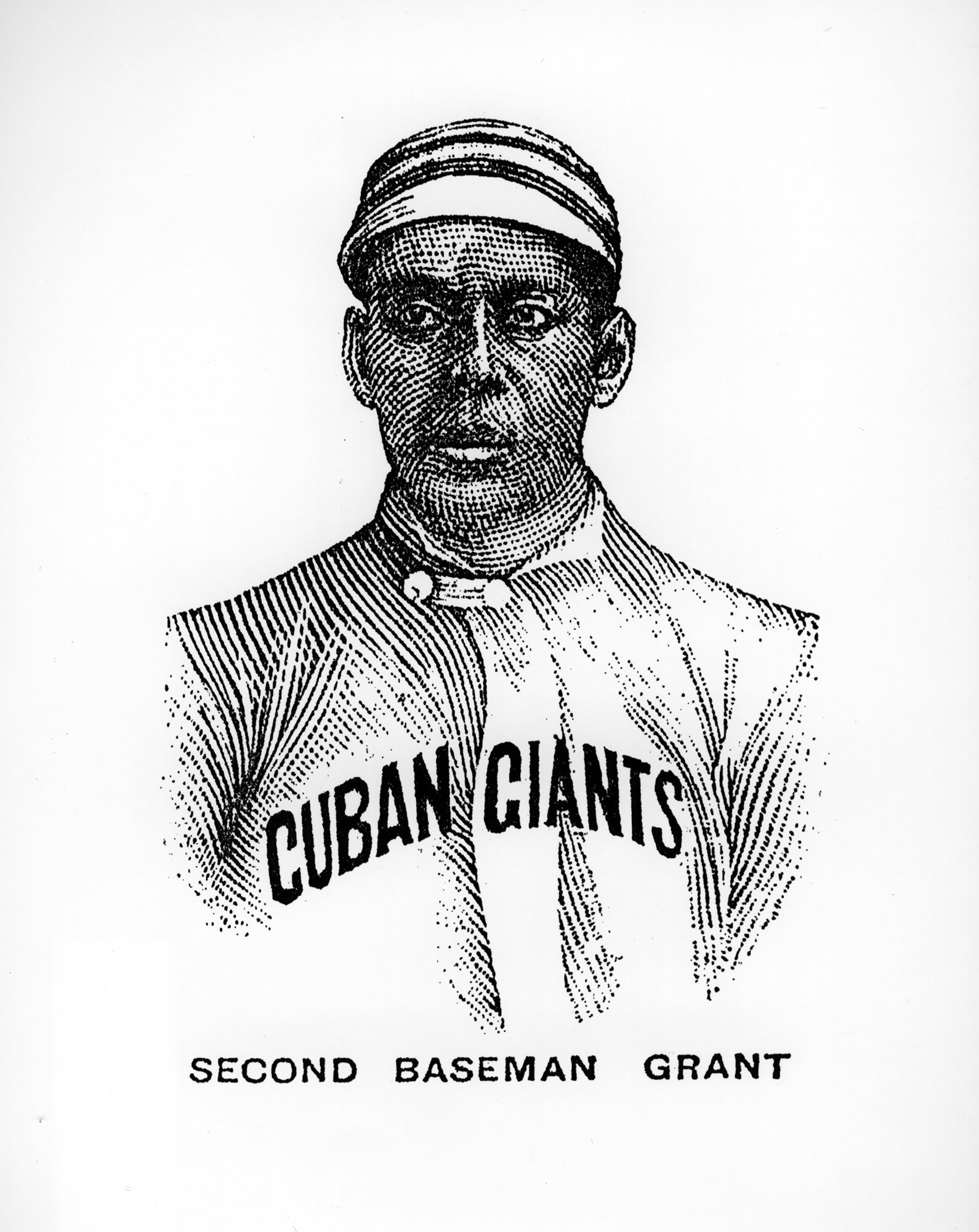

In 1894, Fowler teamed up with Grant “Home Run” Johnson to form the Page Fence Giants, who would go on to become one of the all-time great Black barnstorming teams. It was during the team’s inaugural season that Fowler faced off against a major league team when the Page Fence Giants took on the Cincinnati Reds in a two-game exhibition match-up. They lost against the Reds, but the season proved to be a success – particularly for Fowler himself, who hit .316 on the year. Later on, he had a hand in establishing other barnstorming clubs, including the Smoky City Giants, All-American Black Tourists and the Kansas City Stars, and was a strong proponent of establishing Black baseball leagues. “Some of these days, a few people with nerve enough to take the chance will form a [Black baseball] league of about eight cities and pull off a barrel of money. I know the field is there,” Fowler, who was described in the article as the “patriarch among the Black sons of swat, told the Cincinnati Enquirer in 1905. Tragically, Black baseball’s early leader fell ill just a few years later after retiring to Frankfort, N.Y. “Bud Fowler, probably the greatest [Black] ball player who ever lived and a man well known in the professional baseball world for thirty years is dying here,” wrote the Sporting Life in September of 1908. Though his illness was initially reported to be consumption, Fowler apparently wrote to correct them, claiming “An x-ray examination revealed the fact that he has for six years been suffering from an injury sustained while stealing a base in Indianapolis.” He passed away from pernicious anemia on Feb. 26, 1913. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 2022. “Bud Fowler is a key figure not only in black baseball,” said Bob Kendrick, President of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, “but also baseball history all over.”

Isabelle Minasian was the digital content specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Pre-Negro Leagues stars laid the foundation for integration

Stories: Baseball and Civil Rights

Rube Foster’s writing predicted future of Black baseball

Pre-Negro Leagues stars laid the foundation for integration

Stories: Baseball and Civil Rights