- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jim Roland

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jim Roland

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

This card will forever be known as the “Badger Camp Card.”

That label might sound a little incoherent, so let’s try to explain. Back in the summer of 1972, some 45 years ago, I attended Badger Camp for the first time. Located in Westchester County of New York State, Badger Camp is an all-sports camp that offers a little bit of everything: Swimming, trampoline, basketball, rifle shooting, archery, tennis and softball. The camp is still going strong these days, which is rather remarkable given our ever-changing culture and the tendency of youngsters to use computers and other forms of technology rather than take to the outdoors.

I spent a good portion of the 1970s at Badger Camp. Every summer I balked at going, telling my parents that I would prefer to stay at home and “play in the neighborhood,” even if that involved watching reruns and baseball games on TV most afternoons. To their better judgment, my parents insisted that I go to Badger Camp, realizing that the camp would give me a chance to participate in a variety of athletics while helping me make some new friends along the way. And by the middle of each summer, I realized that they were right.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

The best part of Badger Camp was its unofficial baseball theme. We were given assignments of groups or teams, each led by several counselors and each given a nickname from Major League Baseball, like the Braves or the Yankees or the Dodgers. And since camp coincided with baseball’s regular season, we spent a lot of time talking about the pennant races, the players who deserved to make the All-Star team, and the headline-making stories of the days. Over the years at Badger Camp, we debated and dissected some of the game’s most important developments, including Hank Aaron’s successful chase of Babe Ruth’s home run record and Frank Robinson’s hiring as the game’s first African-American manager. We also talked about the deaths of current-day players, especially Roberto Clemente in that New Year’s Eve plane crash and Danny Frisella in a 1976 dune buggy accident. Those deaths hit us hard.

At Badger Camp, baseball reigned king. You had to be able to talk baseball – the state of the game in the 1970s and its history – or you were in trouble. If you couldn’t talk baseball, you couldn’t keep up.

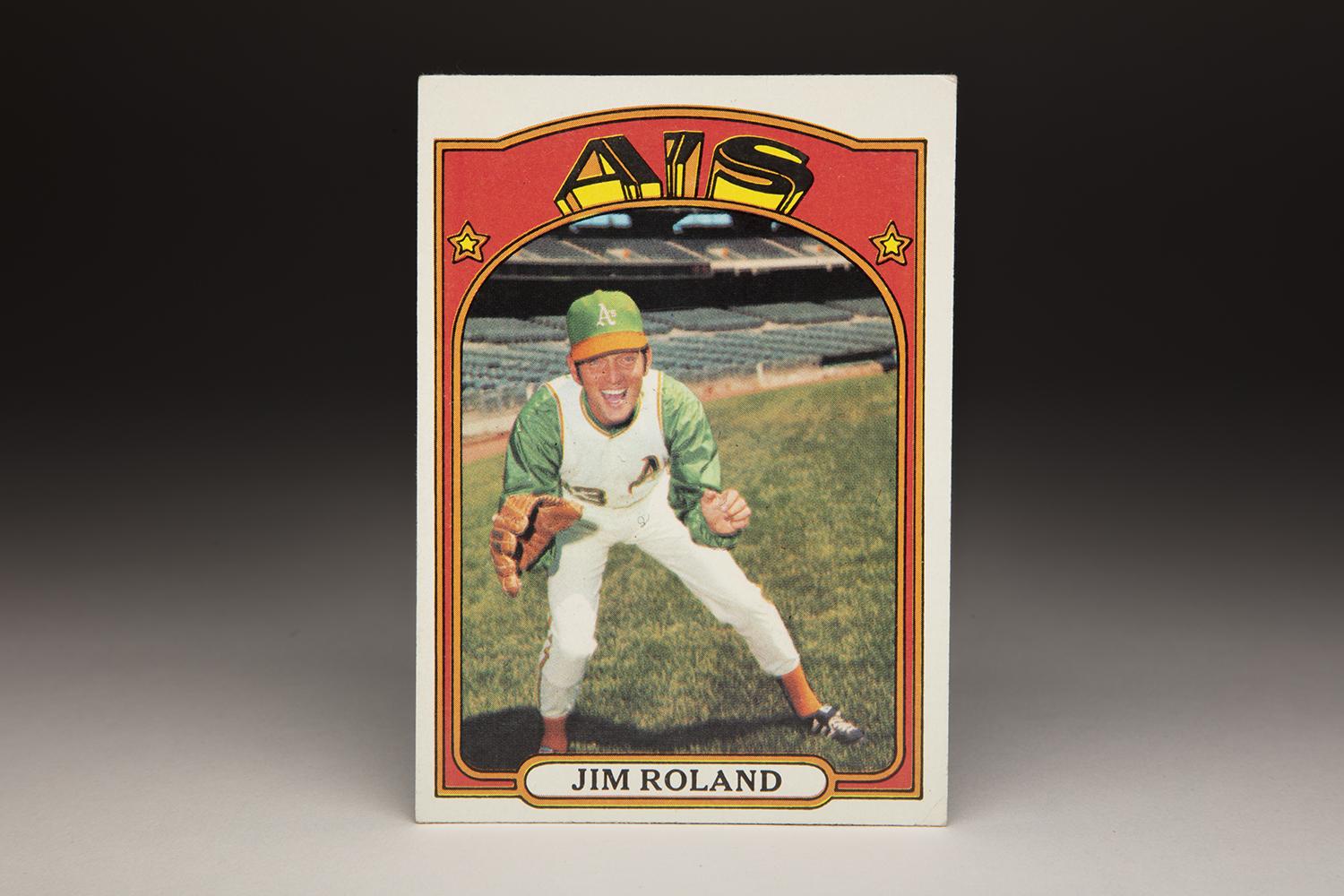

So what does any of this have to do with a pitcher named Jim Roland? Not only did 1972 represent my first year at Badger Camp, but it also marked the start of my days as a collector. I became a rabid card collector that year, particularly when the first few series of cards came out in the spring. By later in the summer, I stopped buying as many cards, simply because I had run out of money. One day, one of the other kids in our group brought in his newest cards, including the card of Jim Roland, which came out as part of Topps’ later series. I asked him to let me see the card more closely. I liked the crisp photography of the card, along with the unusual pose that Roland struck on the card. This was a card I needed to have.

I offered my campmate a swap of cards, several of my own for the Roland. He turned down the offer – and every subsequent offer I made. Despite my best efforts, the Roland card eluded me – at least in 1972.

All these years later, the Roland card still stands out. Roland is smiling widely, almost laughing as he makes a full-out pose for the Topps cameraman. The way that he is bending down, with his arms extended forward, makes him look like he is yelling, “Hit the ball to me!” Or maybe he’s just trying to give the photographer a sudden scare. Whatever it is that he is doing, Roland looks like he’s having a blast. And isn’t that how everyone should look on his baseball card?

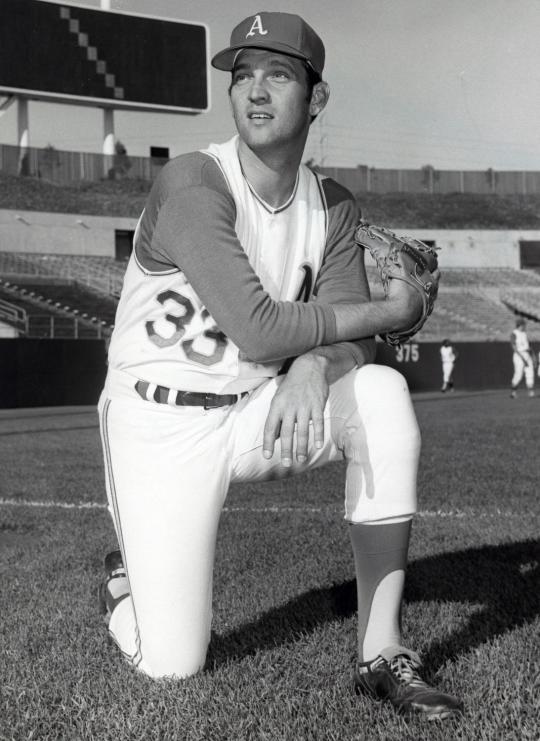

To make matters more fun, Roland gives us a glimpse into the fashion preferences of players back in the early 1970s. Notice how he is wearing a windbreaker jacket under his Oakland A’s vest. This is something that you never see players do anymore, but it was a common tendency for players back in the day. Major leaguers thought that a windbreaker under their jersey made them look cool, a sentiment with which I wholeheartedly agree.

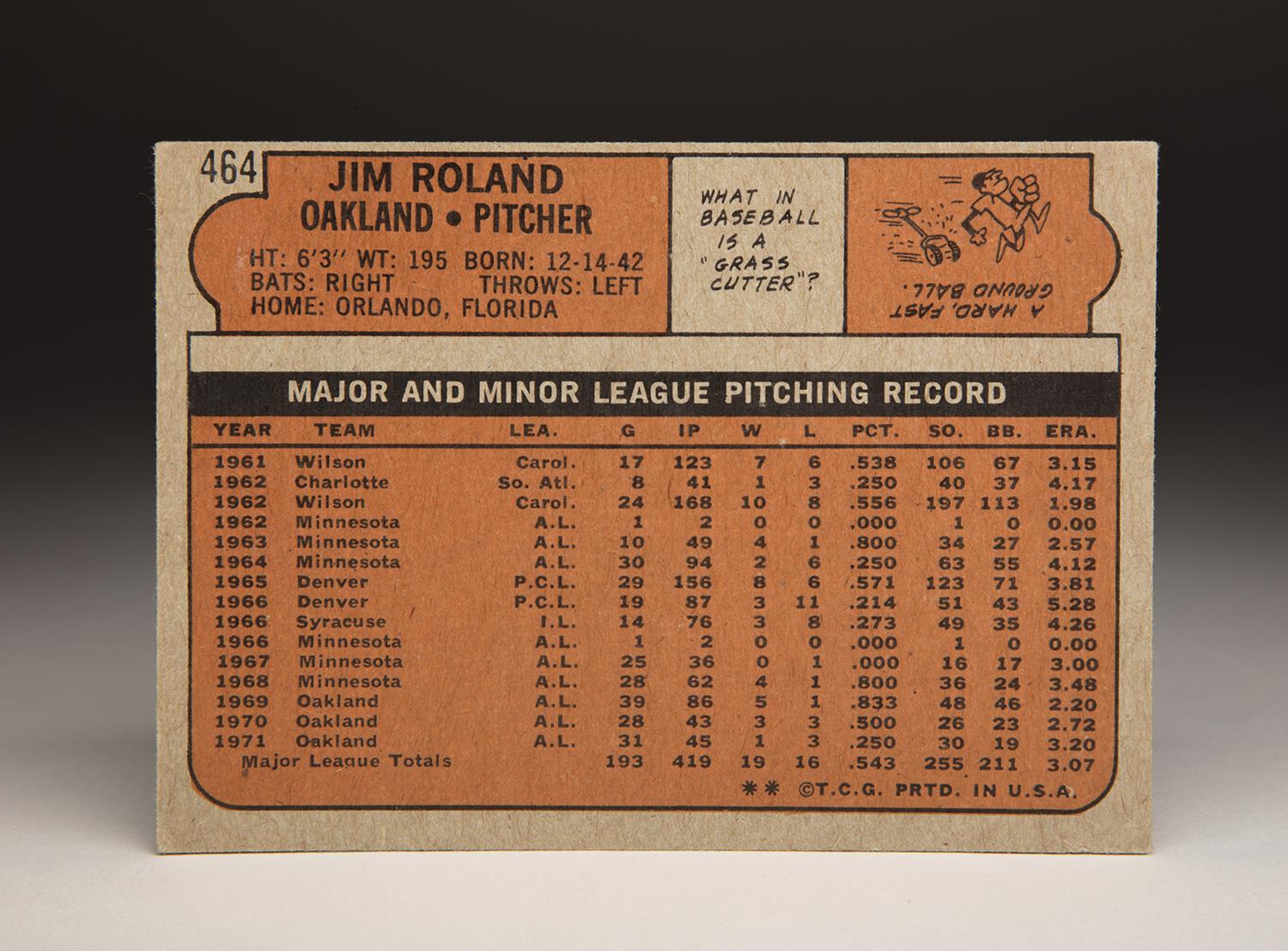

If not for this card, it’s quite possible that I would never have given a second thought to Roland. After all, he was a relatively little known pitcher from the 1960s and early 70s. But his story is an interesting one, one that is worth pursuing. Upon graduation from high school in Raleigh, N.C., the Minnesota Twins signed him and gave him a bonus of $45,000, largely because the rail-thin left-hander could throw a fastball in the mid-90s.

After less than two seasons of minor league apprenticeship, Roland earned a promotion to Minnesota. On Sept. 20, 1962, he made his debut, a successful and scoreless two-inning stint in relief of Jim Kaat. Showing few signs of nervousness, Roland allowed one hit and no runs over two innings. It would turn out to be his only appearance with the Twins in 1962, but it left a favorable impression.

In 1963, Roland emerged as the sensation of the Twins’ spring camp. Not only did he pitch well, but he made plenty of friends with his infectious personality. Constantly smiling and always willing to talk, Roland became popular with both teammates and the media. Thanks to his attitude and his pitching, the 20-year-old made Minnesota’s Opening Day roster, projected to serve as an occasional fifth starter and long reliever.

At times, Roland pitched brilliantly. He pitched a three-hit shutout one day and a five-hit complete game another day. Then came the fateful game of June 5, when Roland held the Kansas City A’s to two hits over seven innings. Though he pitched well, he felt something snap in his elbow.

“A nerve popped in my elbow,” Roland recalled for the Sporting News many years later. “I remember waking up the next morning. I had a brown suit and I couldn’t get the sleeve over the elbow because it was so swollen.” The team physician diagnosed Roland with scar tissue that was “ripping” around the muscle in the elbow. Other than one brief relief appearance, he didn’t pitch for the Twins again that season.

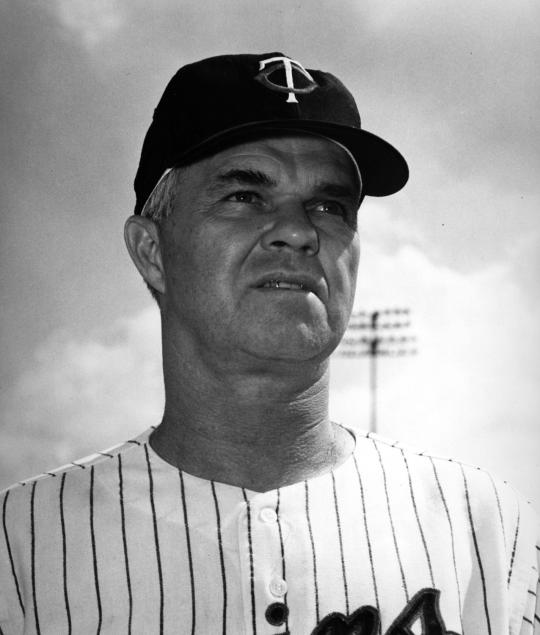

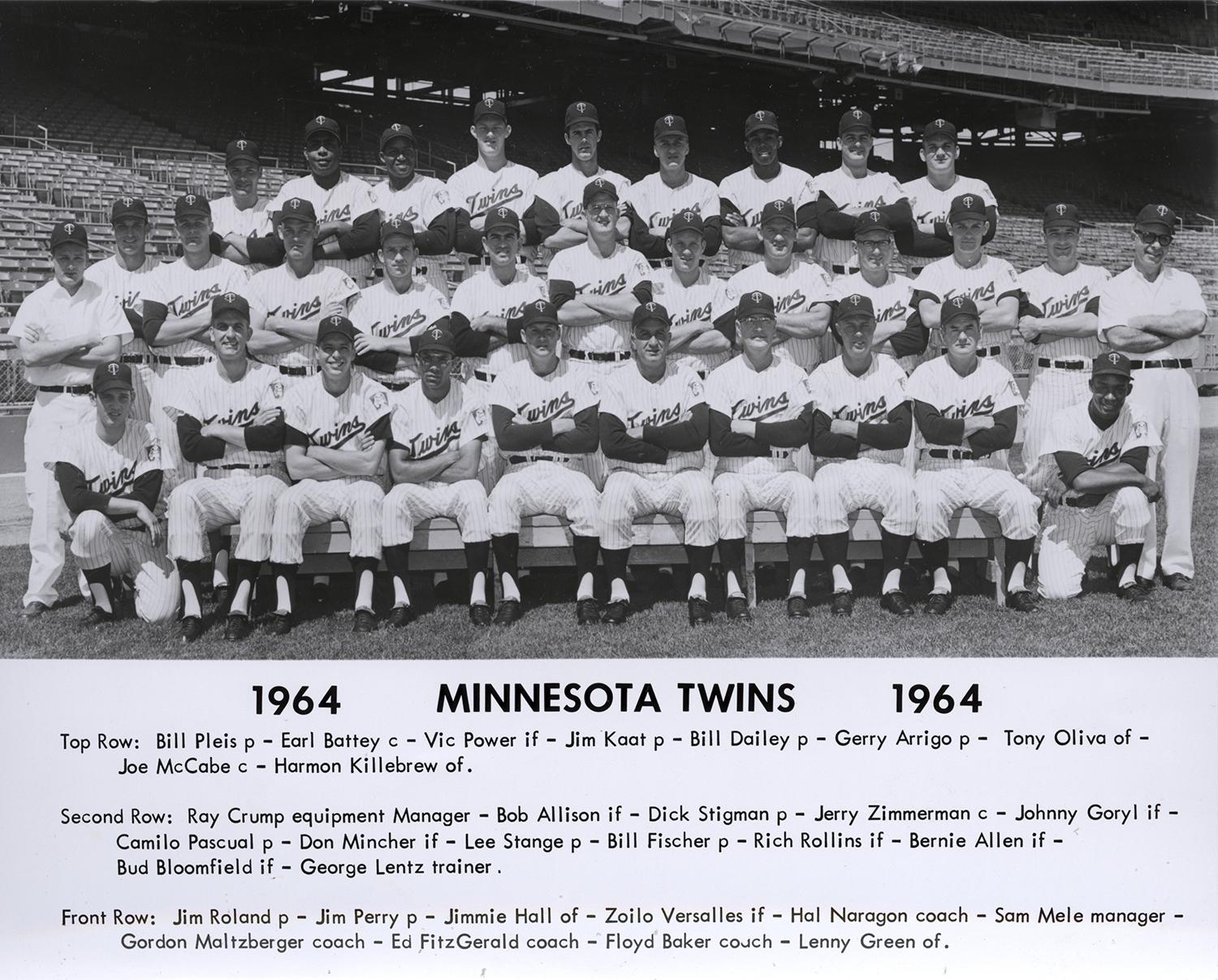

Roland’s arm felt better in 1964, but he also added about 30 pounds of weight. He was perhaps overly thin before, but now tipped the scale in the other direction. “Roland is about 10 pounds overweight,” Twins manager Sam Mele told Twins beat writer Max Nichols. “It’s mostly around his stomach. We’re getting after him to get that extra weight off.” No longer the thin man, Roland won a job in the rotation and added a slider to his repertoire, but after a good start, he began to struggle. That earned him a ticket to the bullpen pitching in a mop-up role. His main problem remained his control, as he walked an average of six batters per nine innings.

The spring of 1965 brought little comfort to Roland. While many of the Twins’ pitchers responded to new pitching coach Johnny Sain, Roland did not. He also suffered a pulled muscle in his thigh and received a demotion to Triple-A. Roland would spend the entire season in the minor leagues, a huge letdown for a pitcher who had already made 41 appearances in his big league career. He also missed out on the Twins’ first trip to the World Series.

Roland hoped for a comeback in 1966. He donned eye glasses for the first time, claiming that poor depth perception had affected his pitching in recent years. Roland did not pitch badly in the spring, but the deep Twins staff created an unfavorable numbers game for the left-hander. With no room on the roster, Roland returned to Triple-A, where he spent most of the season before a brief call-up in September. Even in the minor leagues, Roland struggled, losing 19 games while sporting an ERA of 4.80.

By 1967, Roland had run out of minor league options, so the Twins felt forced to keep him on their roster. He pitched sparingly over the next two seasons, his mechanics falling out of whack because of the infrequent use. Roland put in extensive work with pitching coach Early Wynn, who felt that the left-hander had a bad habit of bending his wrist during his delivery. But the sessions with Wynn failed to produce any tangible results. So the Twins left Roland exposed to the expansion draft, but neither of the two new American League teams chose to take a shot on the veteran left-hander.

In the spring of 1969, Roland came back to the Twins, but he would not remain there for long. In late February, the Twins finally found a taker for Roland. They sold his contract to the Oakland A’s in a straight cash deal. The transaction received virtually no attention, but Roland would pay some dividends for the A’s in both 1969 and ‘70. Pitching almost exclusively in relief, Roland put up ERAs of 2.19 and 2.70, respectively. Even though he lacked the power fastball of his youth, his ability to mix in a change-up, curve ball, and slider made him effective.

Roland’s effectiveness waned slightly in 1971, perhaps because of lingering problems with his right knee, which he had injured in a home plate collision in August of 1970. He returned to the A’s for the start of the 1972 season, but by the time his Topps card hit the shelves of pharmacies and newsstands, he was no longer in Oakland. After only two appearances to start the season, the A’s sold him to the New York Yankees.

Not only did the move prevent Roland from earning a World Series ring with the A’s (who would win it all in ’72), but it resulted in a disastrous tenure in New York. Appearing in 16 games, Roland’s ERA rose to 5.04. By the end of August, the Yankees had seen enough. The Yankees traded him to the Texas Rangers for fellow reliever Casey Cox. Roland pitched even worse for the Rangers than he had for the Yankees. At season’s end, with his ERA above 8.00, Roland drew his release.

At the age of 29, Roland’s career had ended. Although his lifetime ERA was a respectable 3.22, Roland had fallen well short of the expectations the Twins once had for the pellet-throwing left-hander.

Roland returned to his native North Carolina, where he entered the sporting goods business as a sales consultant. He did well in the position and continued to work in sporting goods until January of 2010, when he was diagnosed with cancer. Less than three months later, Roland died, passing away at the age of 67.

Although Roland had fallen out of the spotlight since his playing days, his card has periodically given me reason to pause and consider its importance. When I see that card, I think of Badger Camp, and the good times we had talking baseball and trading cards during those summers in the 1970s. I also think about Roland’s pose on the card. Based on everything I’ve read about him, the real-life Roland was just like he was on that card, full of goofiness, joy and boyish innocence. Beyond that, his friends praised him for his generous nature and his willingness to help others.

For those who say that Roland was just a journeyman left-hander, they are wrong. Jim Roland was so much more than that.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

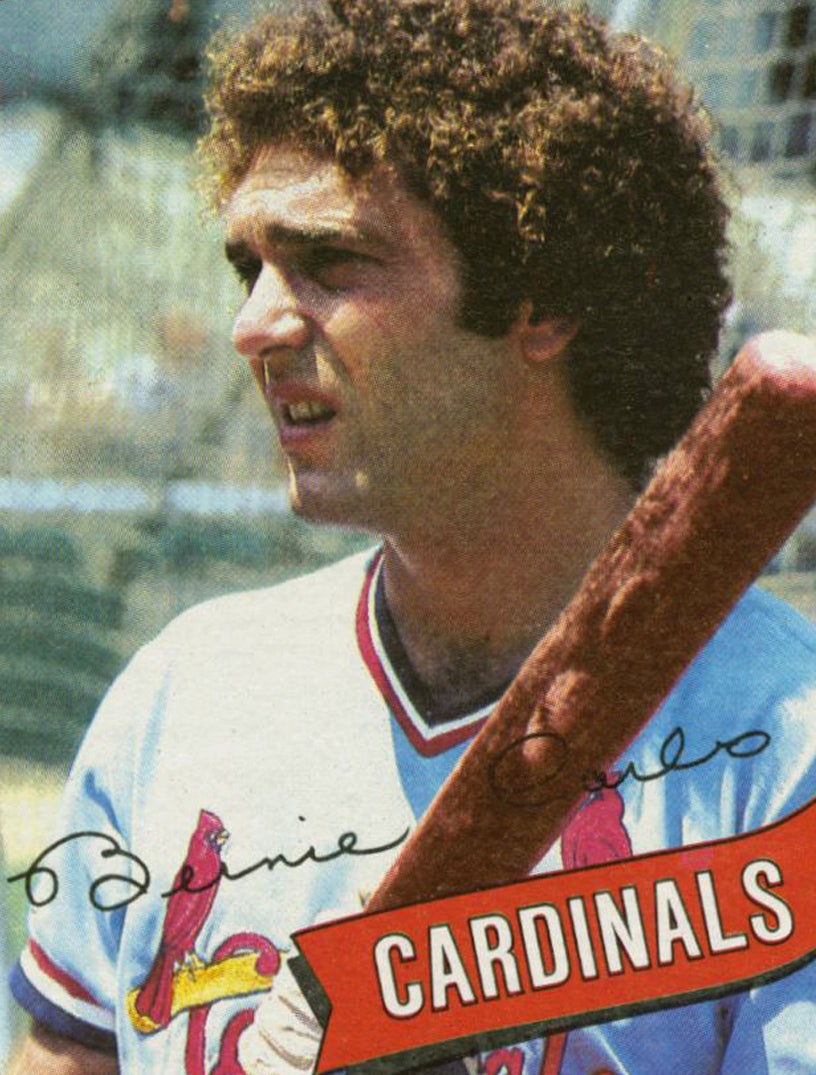

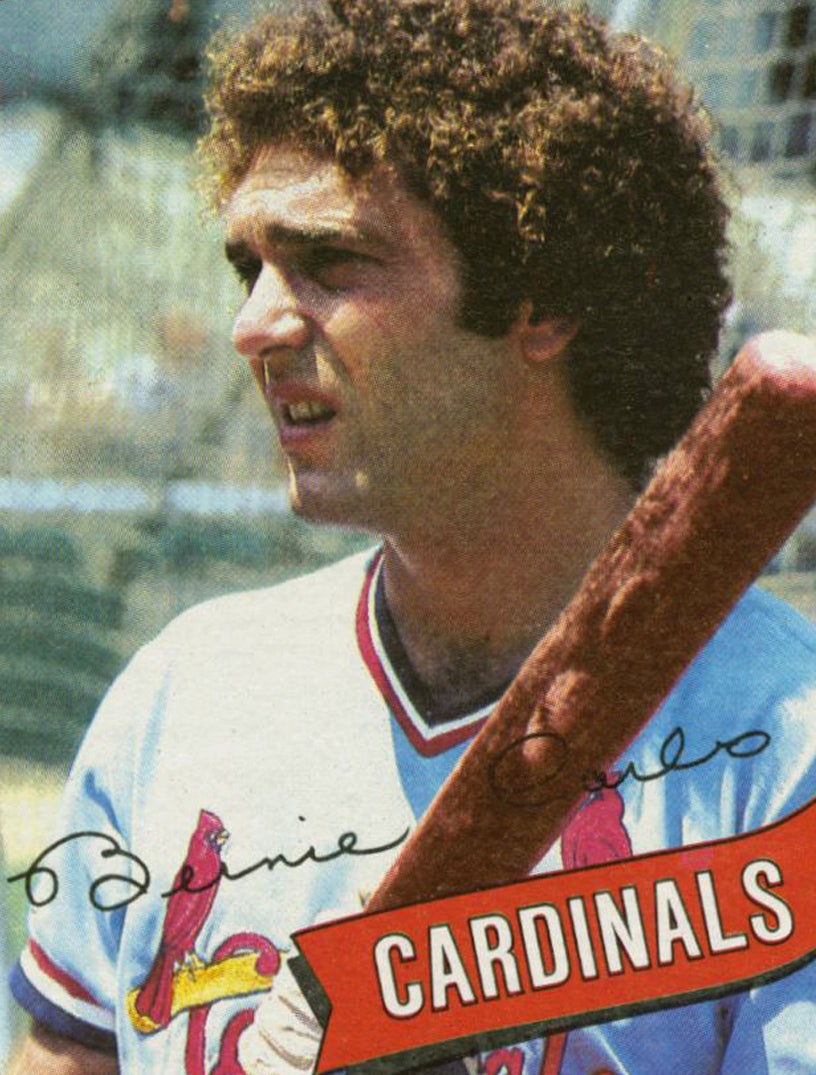

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bernie Carbo

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Easler

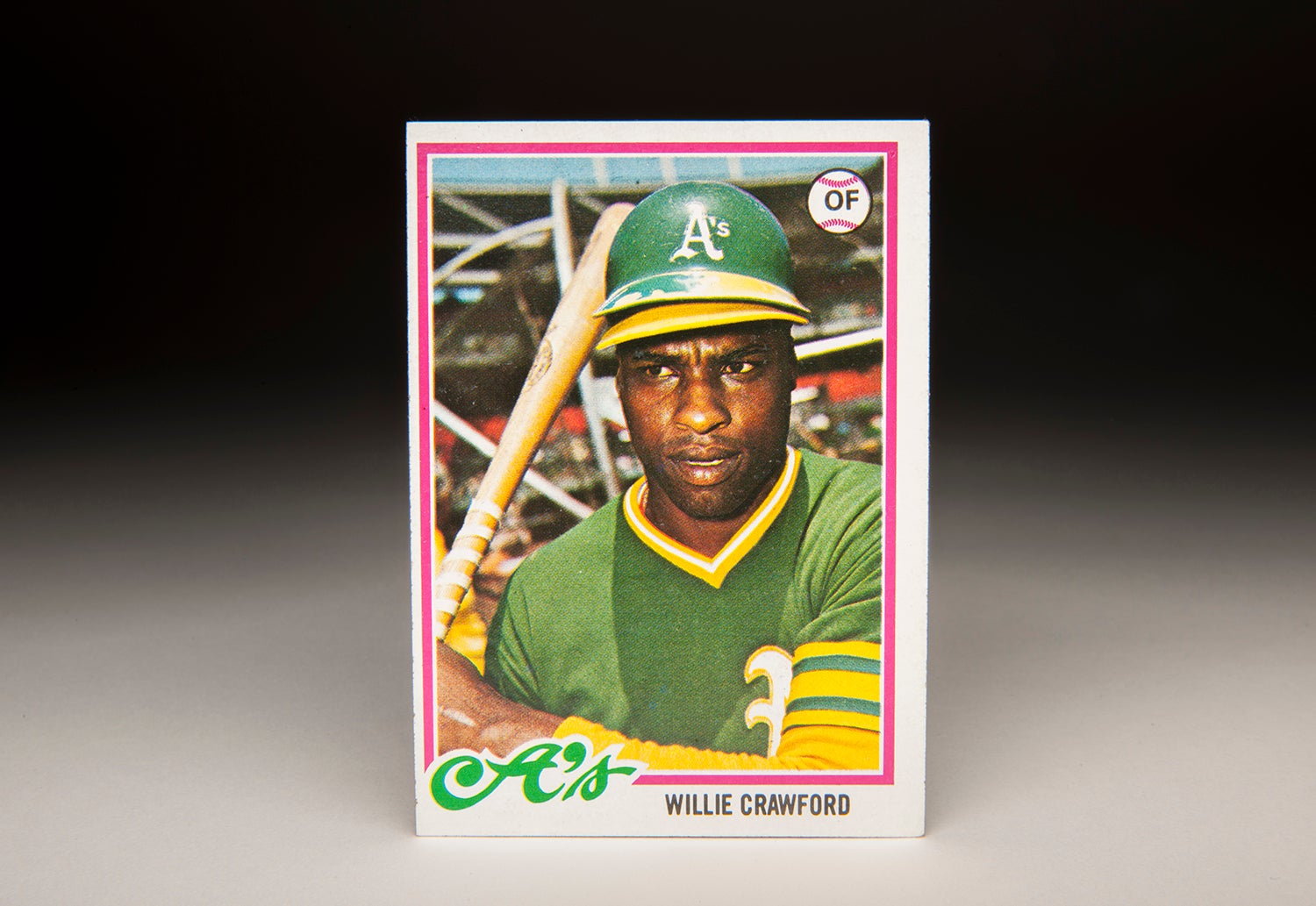

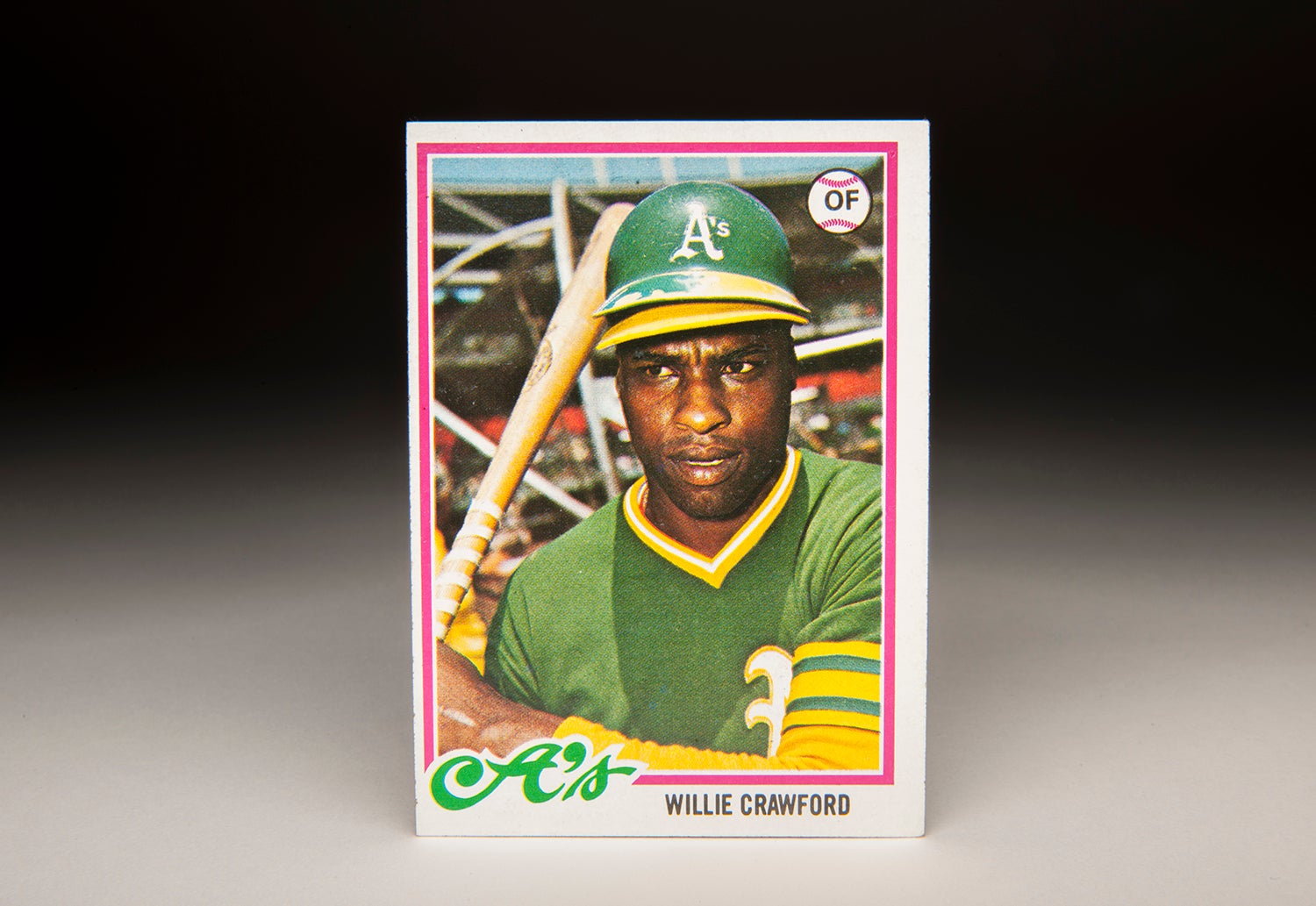

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Willie Crawford

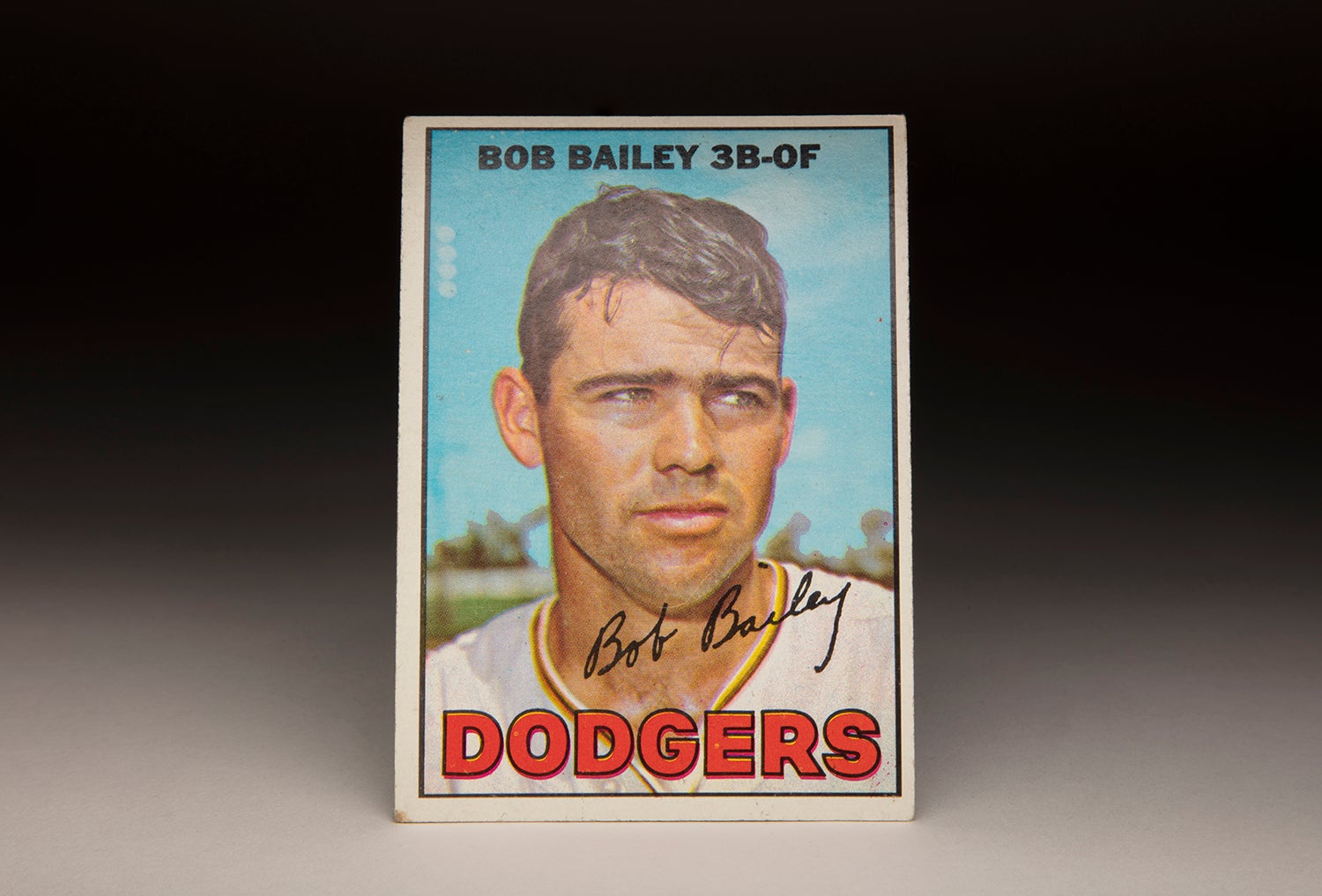

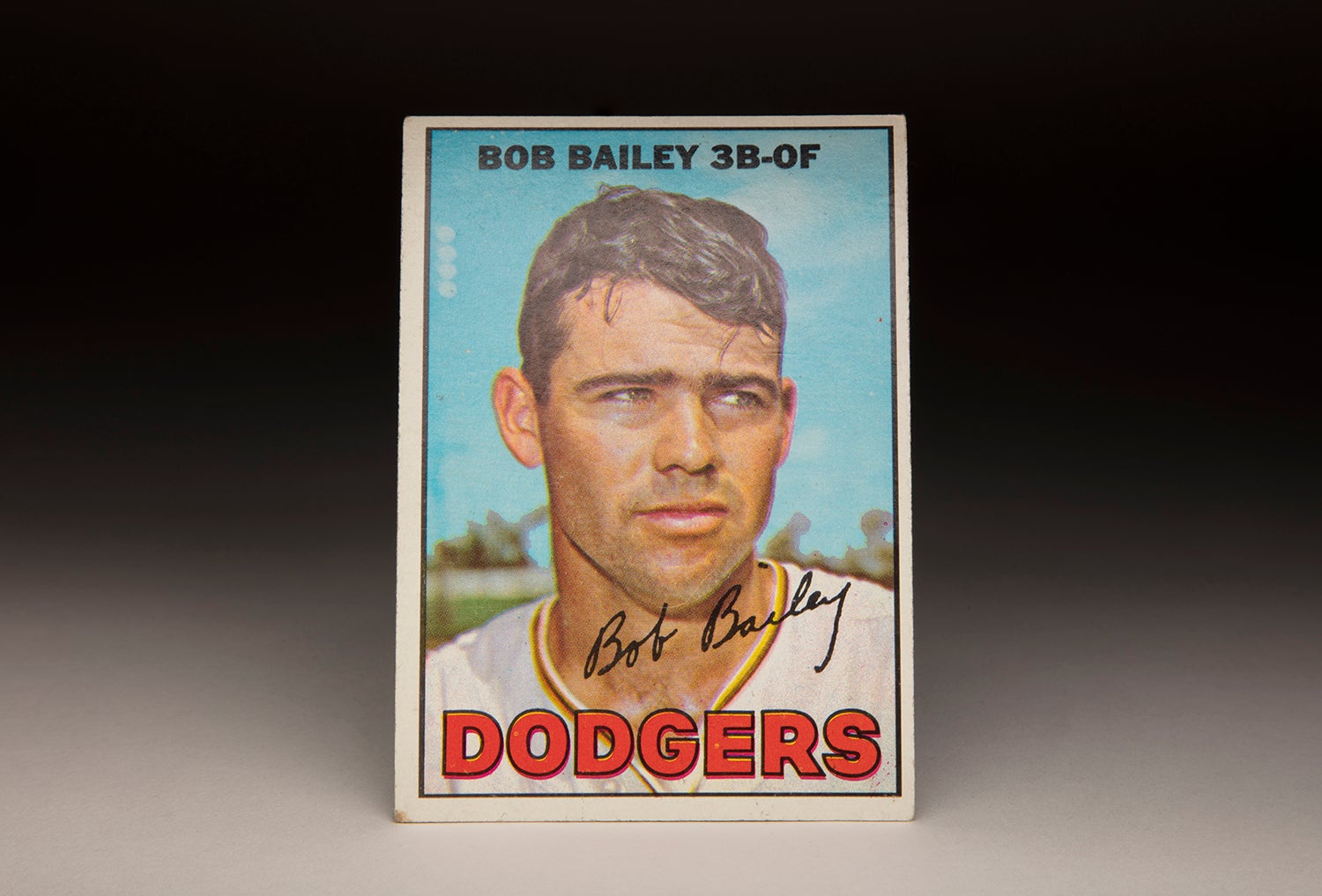

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Bob Bailey

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bernie Carbo

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Easler

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Willie Crawford

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Bob Bailey

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1981 Topps Tom Underwood

The Ultimate Loving Cups

MLK, baseball supported each other in quest of civil rights

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Joe Foy

1968 Hall of Fame Game

1959 Hall of Fame Game

Nolan Ryan becomes baseball’s first million dollar man

1970 Hall of Fame Game

01.01.2023

Two-Time MVP, Brewers Legend Robin Yount Joins Lineup for May 23 Hall of Fame Classic

01.01.2023