- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Kaat

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Kaat

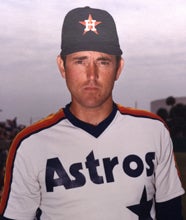

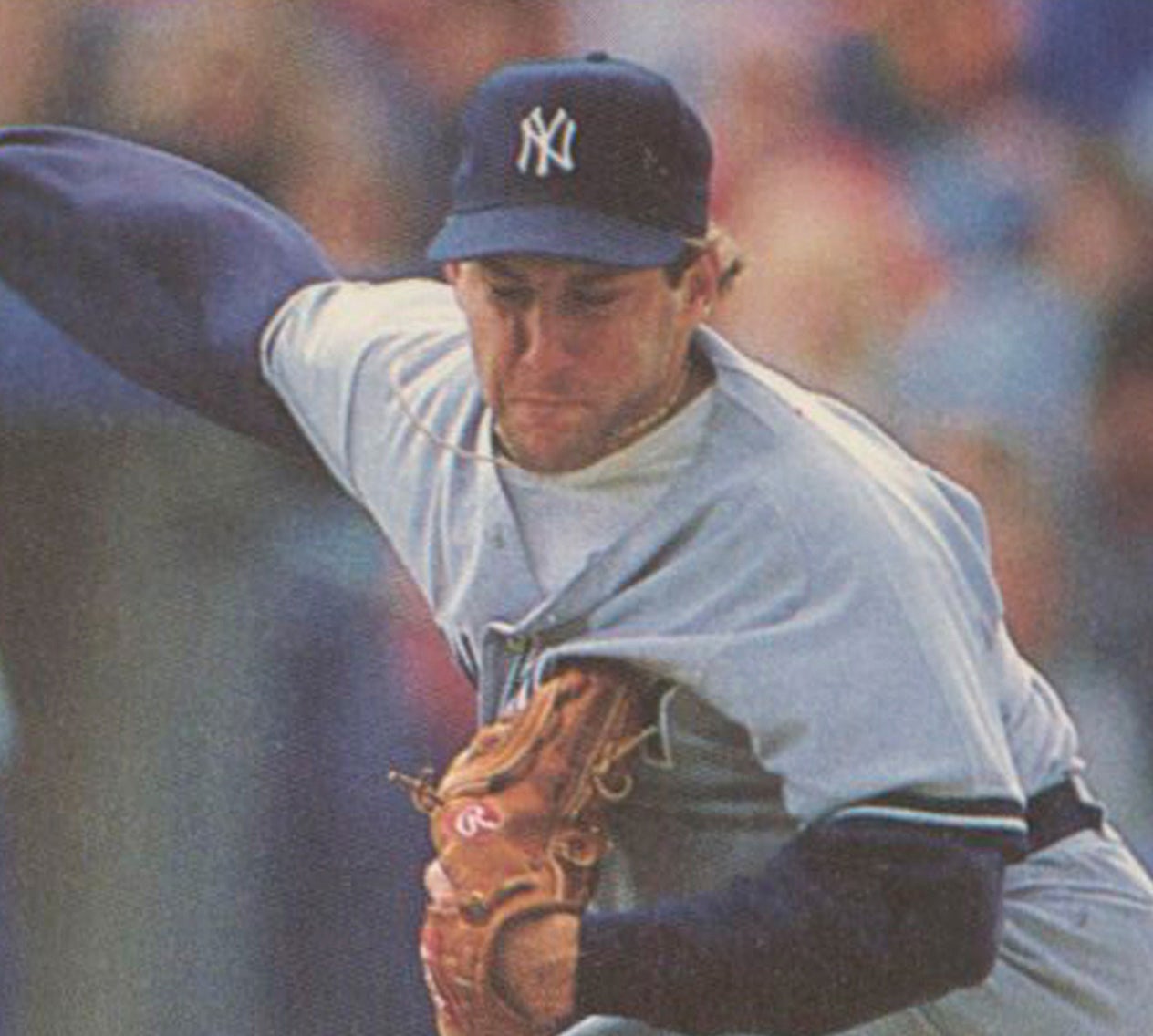

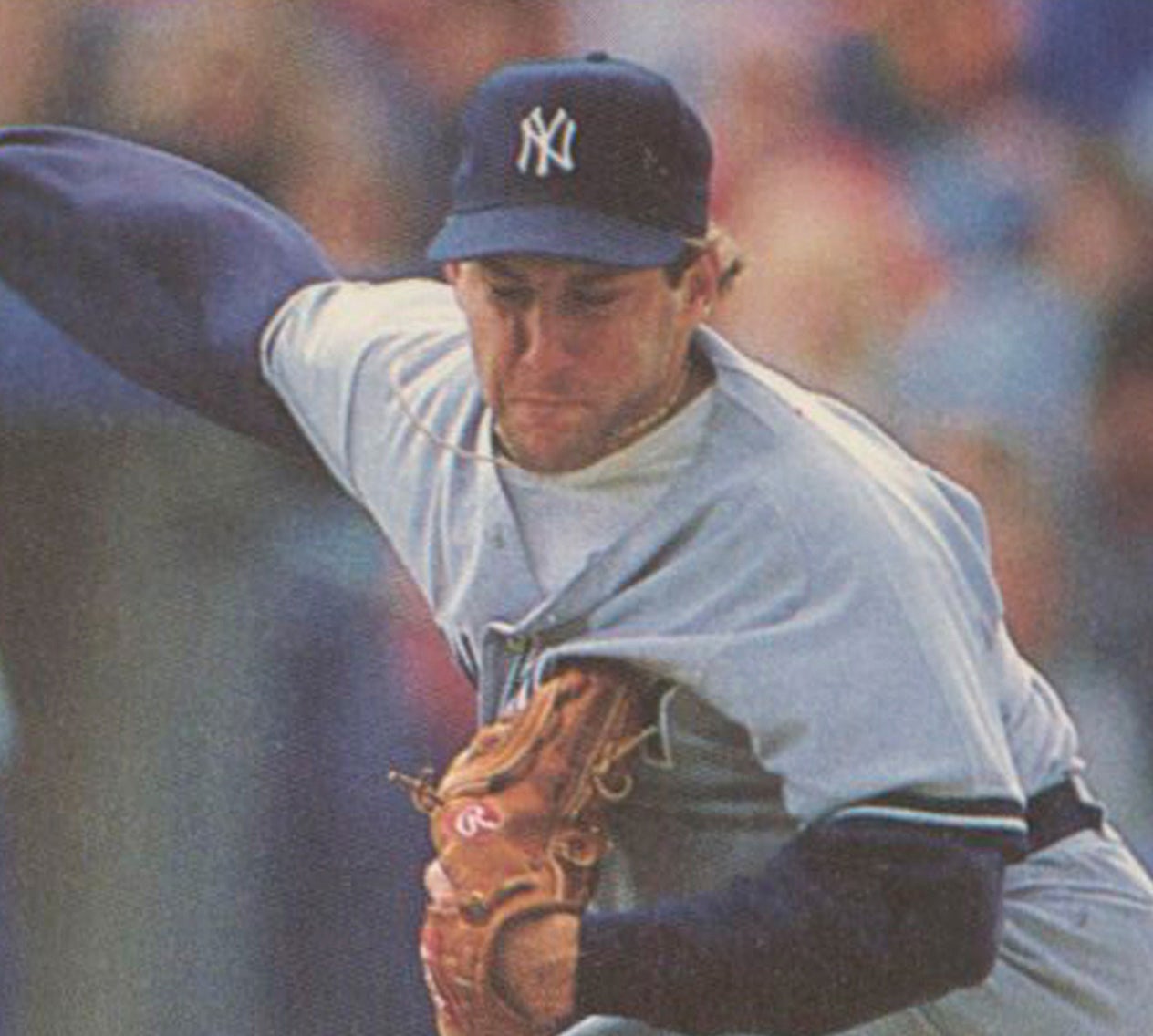

Jim Kaat has not thrown a pitch in a major league game in decades, but I can still picture the unusual pitching motion that he used at the tail-end of his career. It was a three-quarters delivery featuring virtually no windup and the smallest of leg kicks, a delivery that happened so fast that he was often accused of quick-pitching hitters. Even in his earlier years, Kaat’s fuller-bodied motion, which did feature a windup, was also accompanied by a mechanical precision, one that he could repeat over and over. It’s no wonder that Kaat’s career lasted a marathon of a quarter century with only a couple of brief stays on the disabled list.

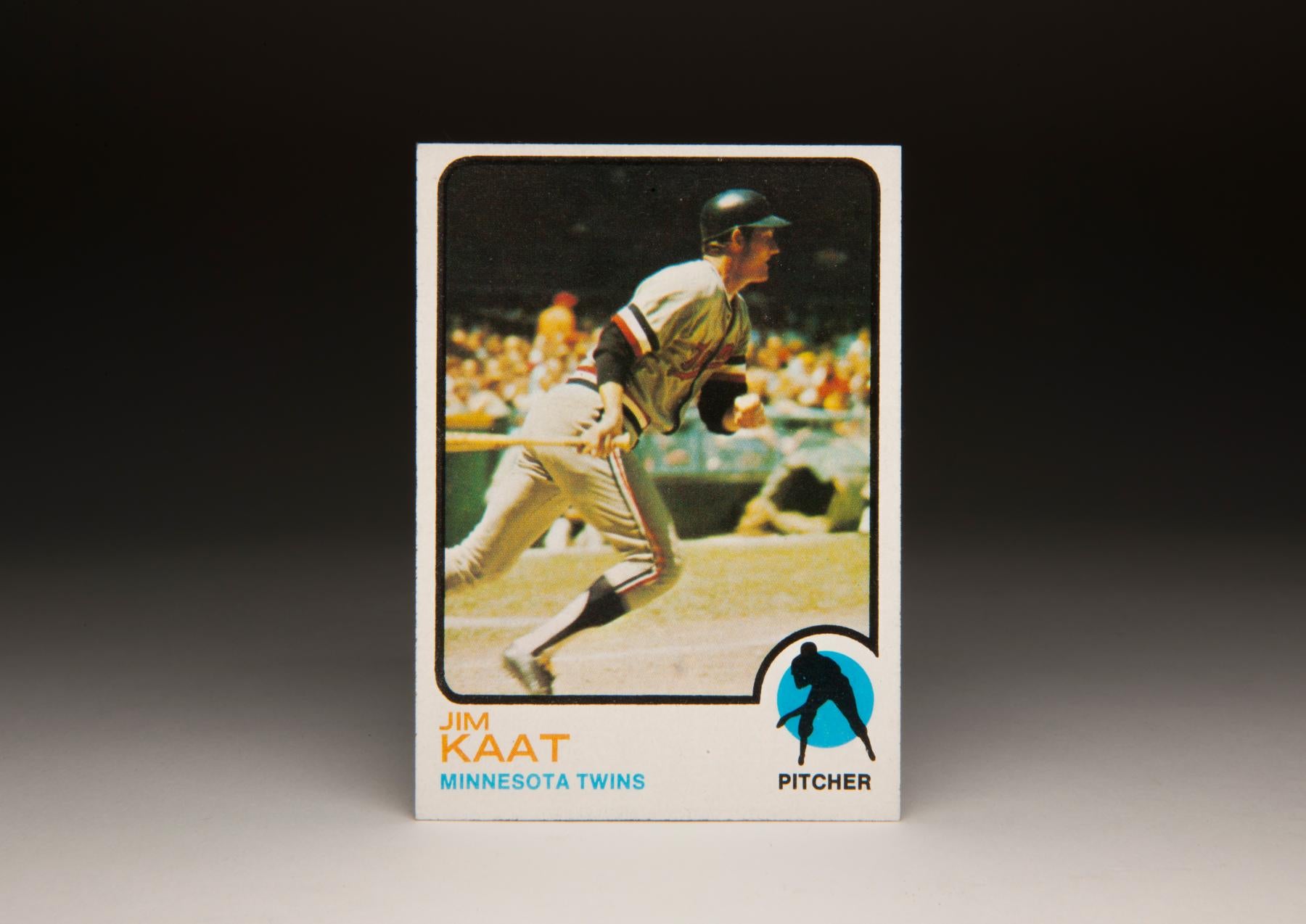

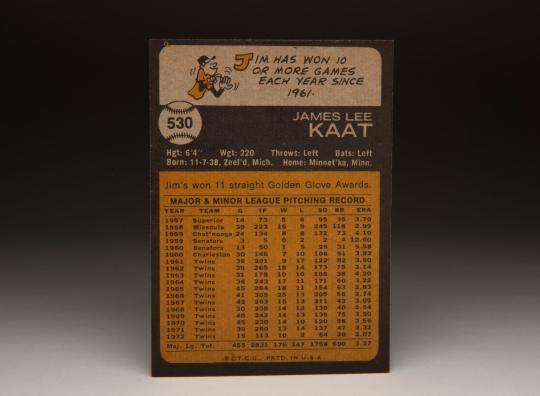

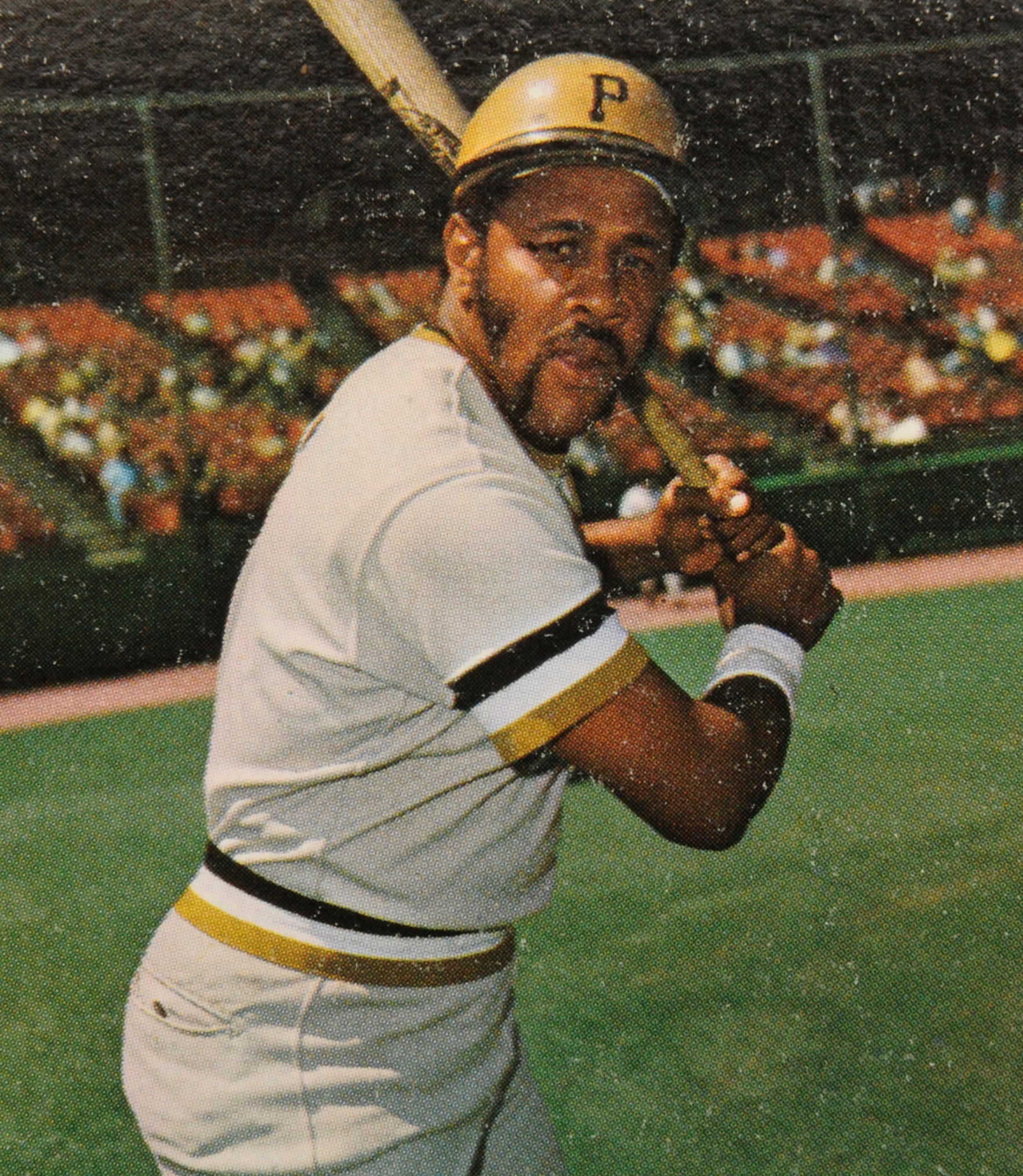

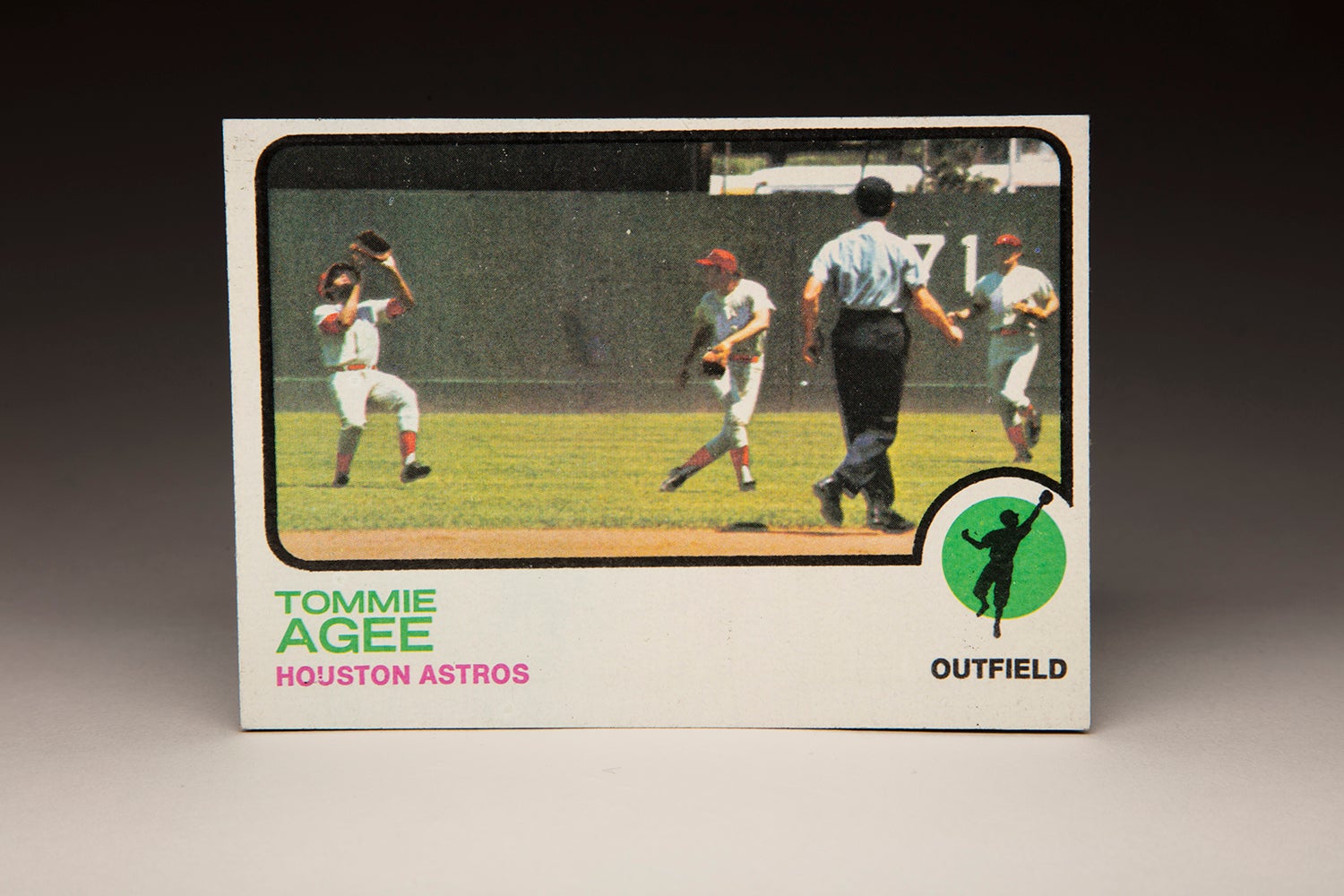

Of course, no part of that pitching motion is evident on his 1973 Topps card. For one of the first times in its history, Topps decided to have some fun and show a pitcher taking an at-bat as a hitter. Topps had introduced action shots of players only two years earlier, so action cards remained a novelty at that point in time. This kind of action shot has become commonplace in recent years, but in 1973, it was practically unheard for a card to showcase a pitcher’s hitting prowess - or lack thereof.

In Kaat’s case, he was actually a fairly skilled hitter. For his career, he batted .185, not bad for a full-time pitcher. At 6-foot-4 and 205 pounds, Kaat had the size of a first baseman. So it should not be surprising that he also clubbed 16 home runs, including three long balls during the 1964 season. As pitchers go, Kaat was no automatic out. He was not someone that opposing pitchers could take for granted.

Ironically, Kaat would not come to bat in 1973, the year of this memorable card. That’s because of the American League’s adoption of the DH rule, which allowed teams to substitute a hitter in the place of the pitcher’s spot in the batting order. With the DH in place, Kaat would not take his next at-bat until 1974, when he came to bat one time for the Chicago White Sox. And then in 1976, Kaat resumed hitting on an irregular basis when he joined the National League’s Philadelphia Phillies.

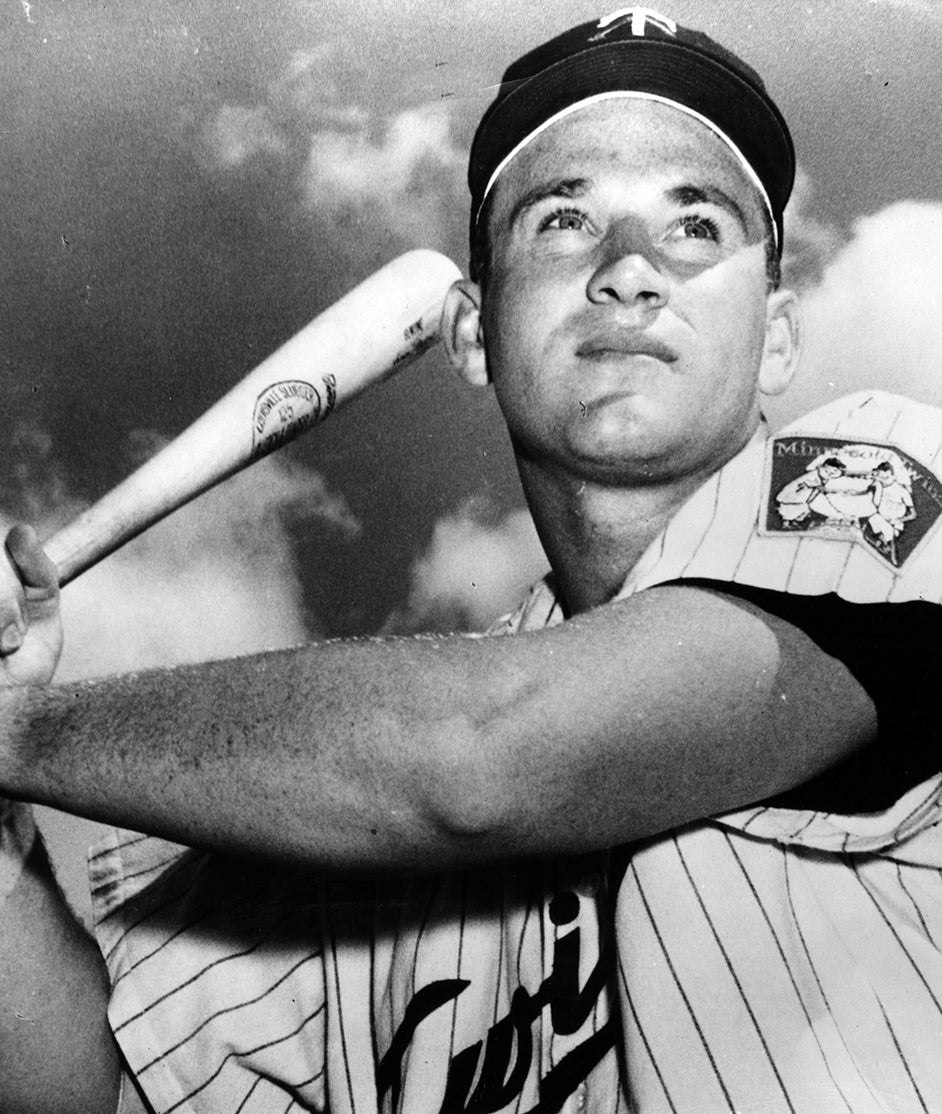

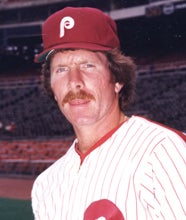

Not only does the 1973 Kaat card show him as a hitter, but it represents one of the better action shots in the set. While the ’73 set has taken some criticism for some of the “long distance” action shots, photographs in which it is difficult to tell which of the players is actually being featured, this card is a well-focused shot of Kaat in his Twins uniform. We can clearly see the side of his face. We can also appreciate the balance that Kaat shows in the batter’s box. Unlike many pitchers, he looks somewhat comfortable holding a bat in hand.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

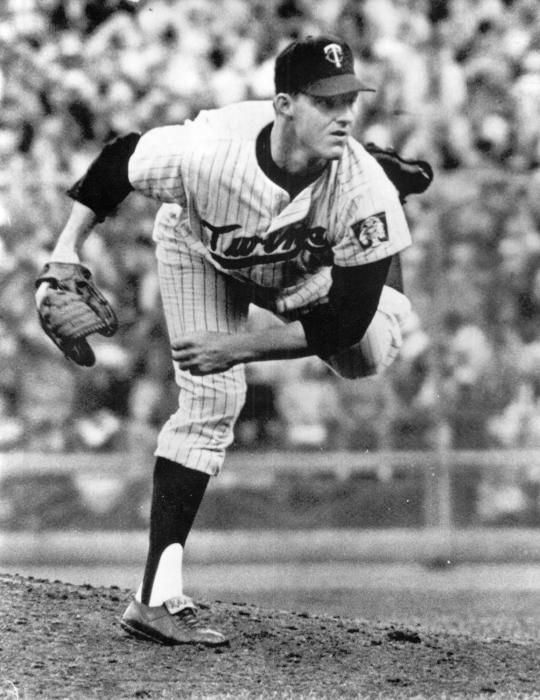

As a pitcher, Kaat enjoyed two careers. The first spanned from 1959 to 1978, when he carved out a niche as a durable and effective starter. After signing with the old Washington Senators in 1957, he made his major league debut only two years later. He became a fulltime member of the franchise’s rotation in 1961, the year that the team moved to Minnesota. From 1962 to 1973, Kaat won in double figures every season for the Twins, culminating in his 25-win season in 1966. He won 11 games for the Twins in 1973 before being picked up on waivers by the White Sox.

Kaat’s durability became legendary. From 1965 to 1967, he averaged 40 starts a season. In 1966, he logged a league-leading 304 innings. He did not hit the disabled list until 1968, when a sore elbow forced him to miss a few starts. Even with that, he still made 29 starts. Then in 1972, a broken bone in his left wrist forced him to the sidelines and limited him to 15 starts.

Over the course of his long tenure as a starter, I came to know Kaat for three attributes. First, he worked very quickly. His philosophy involved getting the sign from his catcher and then throwing almost immediately; at other times, he didn’t appear to come to a complete stop before proceeding to pitch the ball. It was a tendency that some have referred to as quick pitching. (Among current day pitchers, Hansel Robles of the New York Mets uses the quick pitch at times.) Kaat often caught hitters off guard, simply because they were so used to pitchers taking anywhere from eight to 15 seconds in between pitches. Second, he was a skilled and highly conditioned athlete who could run and hit better than most pitchers. And third, Kaat could field his position like no other moundsmen. With catlike reflexes and a quick pickoff move to first base that reinforced his nickname of “Kitty” (which was also a play on his last name), Kaat snared a then record 16 Gold Gloves, the highest total for a pitcher before the days of Greg Maddux.

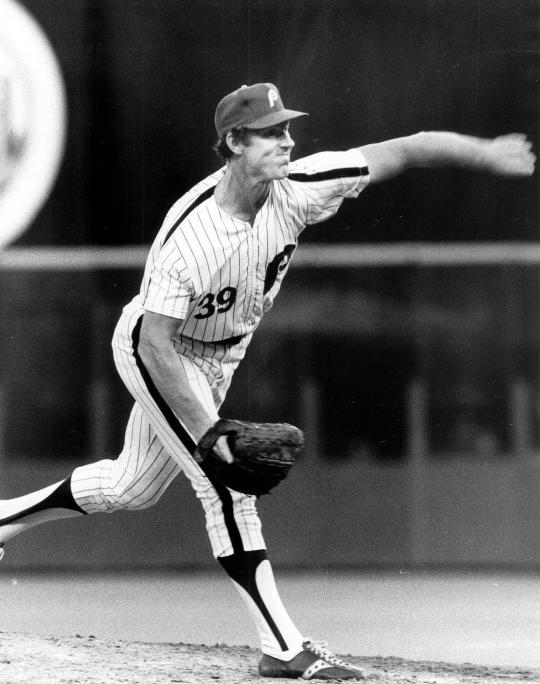

After joining the Phillies in the mid-1970s, Kaat pitched a few more seasons as a starter before moving on to a second career in the bullpen. He worked as both a set-up reliever and long man. Along the way, he played parts of two seasons for the New York Yankees, in 1979 and 1980, before being sold to the St. Louis Cardinals. He could no longer pitch like he once did, but his conditioning left his body looking virtually the same as it had throughout much of the 1960s and '70s. Becoming a favorite of manager Whitey Herzog, he remained with the Cardinals through July of 1983, by which time he had celebrated his 44th birthday.

When he retired in 1983, Kaat became the last member of the original Washington Senators to call it quits, a tribute to his longevity. His career spanned the administrations of seven different American presidents, a record that would eventually be matched by Hall of Famer Nolan Ryan.

Kaat took his vast knowledge of pitching and his high intelligence to his next job: pitching coach. Pete Rose, his former teammate with the Phillies and by now the manager of the Cincinnati Reds, hired Kaat as his pitching coach in 1984. In 1985, his lone full season as a coach, Kaat oversaw a 20-win season by Tom Browning and a career year for closer Ted Power.

Ultimately, the demands of travel and some disagreements over pitching philosophy led Kaat to give up coaching and move toward broadcasting. At first, he worked in the Twins booth from 1988 to 1993. When Tony Kubek retired from the Yankees’ booth after the 1994 season, he left behind a crater-sized void at the Madison Square Garden Network, then the flagship station of the franchise. If nothing else, Kaat reduced the crater to a nick. With his even-keeled commentary and subtle sense of humor, his unending insights on the intricacies of pitching, and his genuine appreciation of the game’s history, Kaat made nightly telecasts on MSG and later the YES Network a mandatory pleasure. Even in losses, I came away from Yankee broadcasts learning something new about the fine art of pitching, especially as it pertained to the pitchers on the Yankees staff. One night, it might be mechanical flaws in Ted Lilly’s delivery, the next it might be a dissertation on side-arming Jeff Nelson and his Frisbee slider. Other than Kubek, no broadcaster taught me more about the finer side of the game than Kitty.

As with any broadcaster, Kaat has his share of critics. Some from the Sabermetric community have chided Kaat for being too “old school,” mostly because he has never bought into the rigid following of pitch counts and pitch limits. But I’ve always felt that Kaat had a reasonable approach to pitch counts. I never heard him call pitch counts worthless; he simply felt that they needed to be looked at within context. As Kaat might say, “Don’t just tell me what the pitcher’s pitch count it, but tell me whether he’s laboring or cruising, whether his mechanics are good or bad that day, and whether he’s had to throw too many sliders or splitters.” In that context, pitch counts can be a useful guide. They just shouldn’t be the be-all and end-all of determining whether a pitcher has had enough that day and needs to be replaced by a fresh relief pitcher. Kaat’s reasoning seemed like a perfectly rational way of thinking to me.

So it was with some sadness that I heard about Kaat’s intention to retire from broadcasting near the end of the 2006 season. The rumors had swirled for weeks, but Kaat did not officially announce his plans until Sept. 10, in the midst of a late-season game against the Toronto Blue Jays. Kaat made it seem that his retirement decision came down to the standard issues of advancing age and fatigue, but it really stemmed from a desire to tend to his ailing wife, who was seriously ill at the time. Less than a year later, MaryAnn Kaat succumbed to cancer, with Jim at her side.

After taking some additional time to mourn the passing of his partner of 22 years, Kaat decided to end his retirement, partly at the urging of fellow broadcaster Tim McCarver and Kitty’s business manager, Elizabeth Schumacher. In 2009, Kaat returned to the booth as an analyst with the MLB Network. He has provided analysis on occasional games ever since, giving fans at least a small dose of the kind of wisdom he dispersed on a nightly basis to Yankee fans.

Even though Kaat is now 77, he remains active both as a broadcaster and on the old-timers circuit. He is now remarried, to Marge. Back in 2009, he brought his new wife to Cooperstown as part of his participation in the annual Hall of Fame Classic. For Kaat, it was just the latest in a long line of visits to Cooperstown.

“I guess [my interest in the Hall of Fame] started as a kid because my dad was such a baseball historian and a baseball fan,” Kaat told me that day at Doubleday Field. “I have a picture of him on my desk standing in front of the old museum in 1947; you can imagine what it looked like then, and that was the year of Lefty Grove’s induction to the Hall of Fame. So that was my start, where the attraction began. And then I was here playing the Hall of Fame Game in 1966, when Stengel and Williams got inducted - Casey Stengel and Ted Williams. The Cardinals brought up a skinny young left-hander to pitch against us [the Twins], a pitcher from Triple-A named Steve Carlton. Since then, we [the White Sox] played the Hall of Fame Game in the '70s, when Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford got inducted [in 1974], and then I was here as a supporter to [former teammate] Harmon Killebrew. Then along came Steve Carlton and Mike Schmidt and Harry Kalas and Richie Ashburn, and a few years ago Bruce Sutter.”

Not only did Kaat’s recall of those visits impress me that day, but so did his physical conditioning. If you could take away the lines on his face, he looked pretty much the way he did when he pitched for the Phillies, Yankees, and Cardinals. He still had that V-shape, with those broad shoulders and that slim waistline. All those years later, Jim “Kitty” Kaat looked like he could still handle a bat and crank up a pretty good swing in the batter’s box.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

More Card Corner

#CardCorner: 1990 Score Lance McCullers

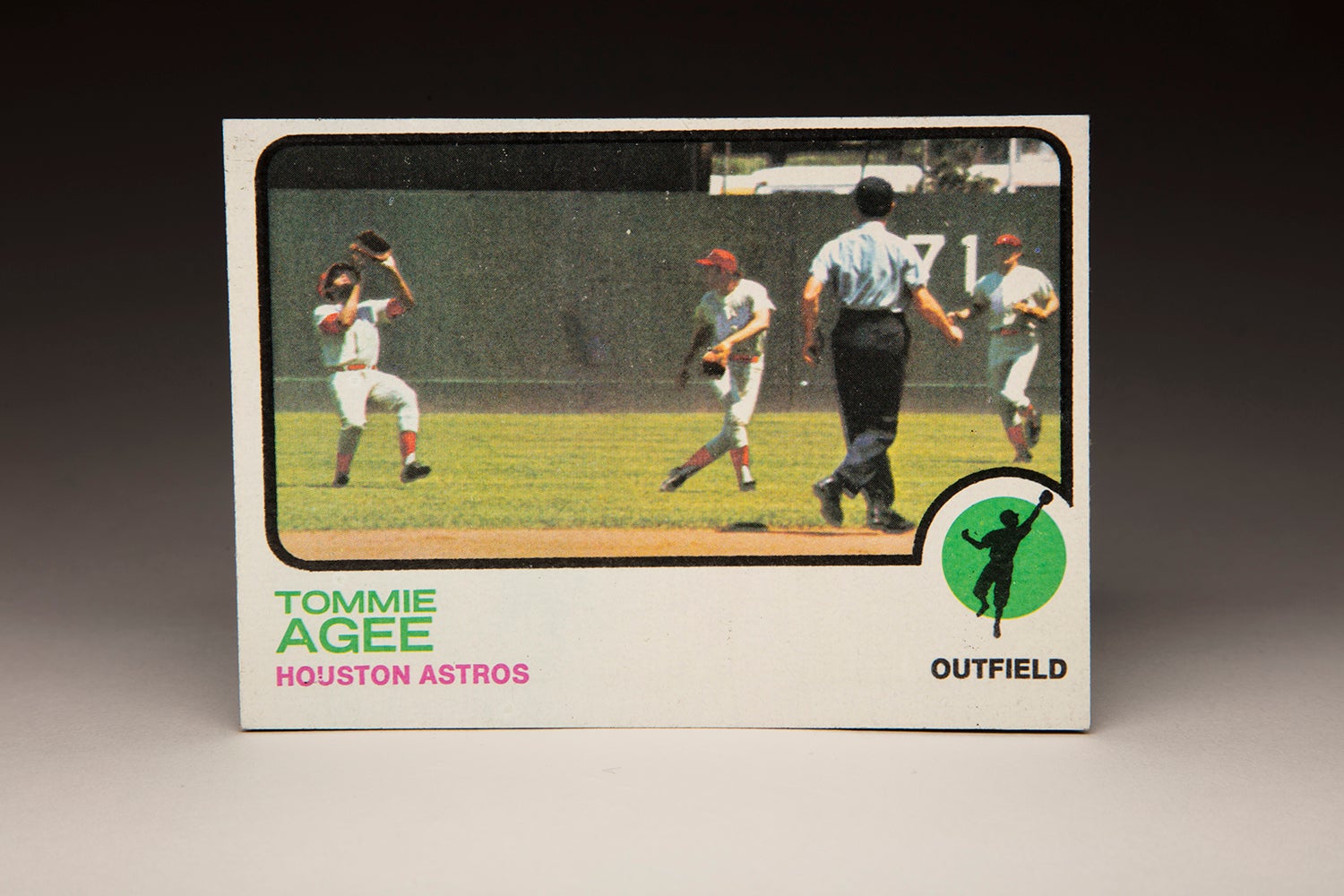

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Tommie Agee

#CardCorner: 1990 Score Lance McCullers

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Tommie Agee

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

Davey Johnson’s managerial skills lead him to Cooperstown’s doorstep

Yankees Slugger Alfonso Soriano Headed to Cooperstown for Hall of Fame Classic, May 23

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Pagliarulo

Hall of Fame Matchup

Museum Partners with Artist Bill Purdom for 75th Anniversary Artwork

Ten Named to Today’s Game Era Ballot for National Baseball Hall of Fame Consideration

Taking his cut

Fans to Cast Their Votes for Frick Award Ballot Candidates

01.01.2023