- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Ray Hart

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Ray Hart

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

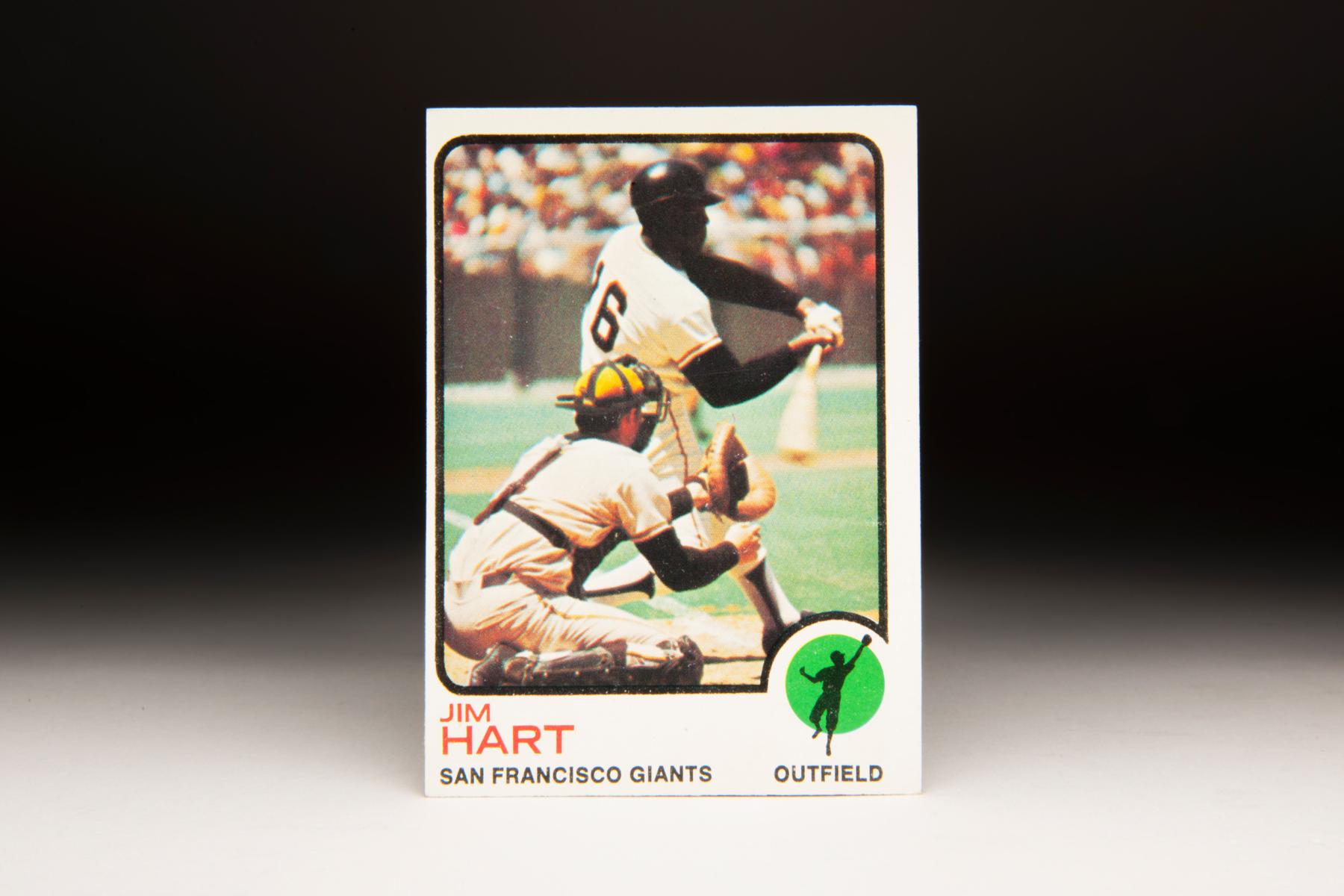

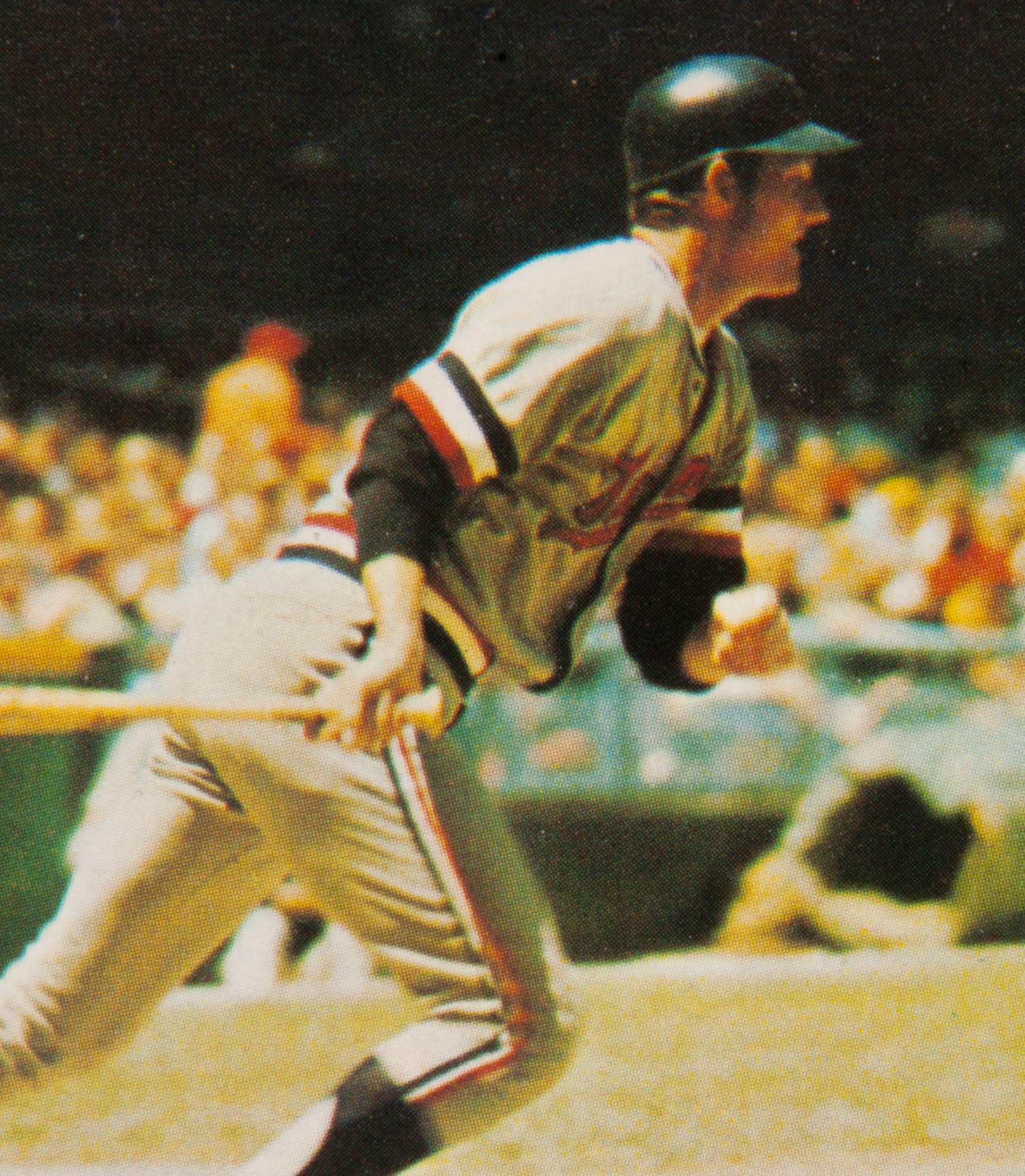

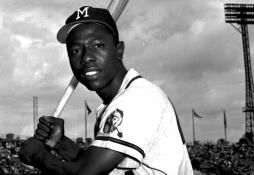

For a card collector, it all comes together when you find a great card of a favorite player. For me, such a card can be found in the 1973 Topps set. It’s an action shot of Jim Ray Hart, the final card that shows him playing for the San Francisco Giants.

After debuting action cards in 1971 and highlighting those kinds of cards in 1972, Topps went full action crazy with its 1973 set. Action shots popped up everywhere, for star players, middle of the road journeymen, and borderline major leaguers. Many of the action shots were a bit unusual. In some cases, players seemed to be photographed from hundreds of feet away, sometimes from the upper deck of the stadium it seemed, so that the players looked indistinguishable. In other cases, action shots captured groups of three or four players, making it difficult to tell which player was actually being featured on the card.

None of those problems arise with the card of Jim Ray Hart, who can be seen wearing his usual No. 16. This is clearly the Giants’ veteran third baseman/ outfielder, in the middle of a swing against the San Diego Padres at Candlestick Park. The game is either from the 1972 season, or possibly from 1971. Take a look at the torque being exerted on the bat; Hart’s bat appears to be bending as he moves it forward. Perhaps it is a sign of Hart’s brute strength. He was a massive slugger, with incredible upper body musculature and strong forearms, and all of that is evident in this clear, focused photograph. All that is missing is a look at his face, but that is sometimes a necessary sacrifice with an action shot.

Still, there is more to the card. Take a look at the Padres’ catcher (possibly Bob Barton), who appears to be lunging forward in an attempt to catch the pitch before Hart can make contact. It’s as if Barton (or whoever the catcher might be) senses that Hart is about to crush the pitch. Of course, if Barton’s glove comes into contact with Hart’s bat, the umpire will have every right to call catcher’s interference, awarding Hart first base.

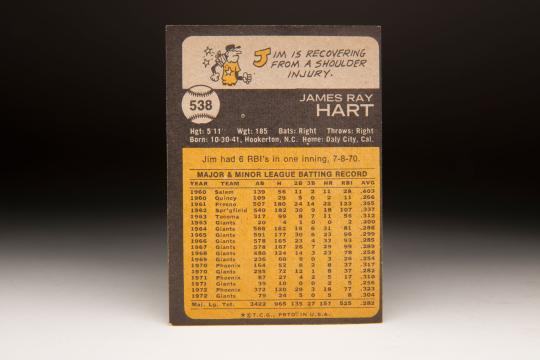

There is also one oddity to the card. Topps lists the featured slugger as “Jim Hart,” even though he was commonly known as Jim Ray Hart. In fact, almost all of the Topps cards do that. I’m not sure why - it’s not as if Jim Ray Hart is a long name - but it’s one of those intriguing Topps tendencies. It was not until the next year, 1974, that Topps identified him fully as Jim Ray Hart. That turned out to be the final card of Hart’s career.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

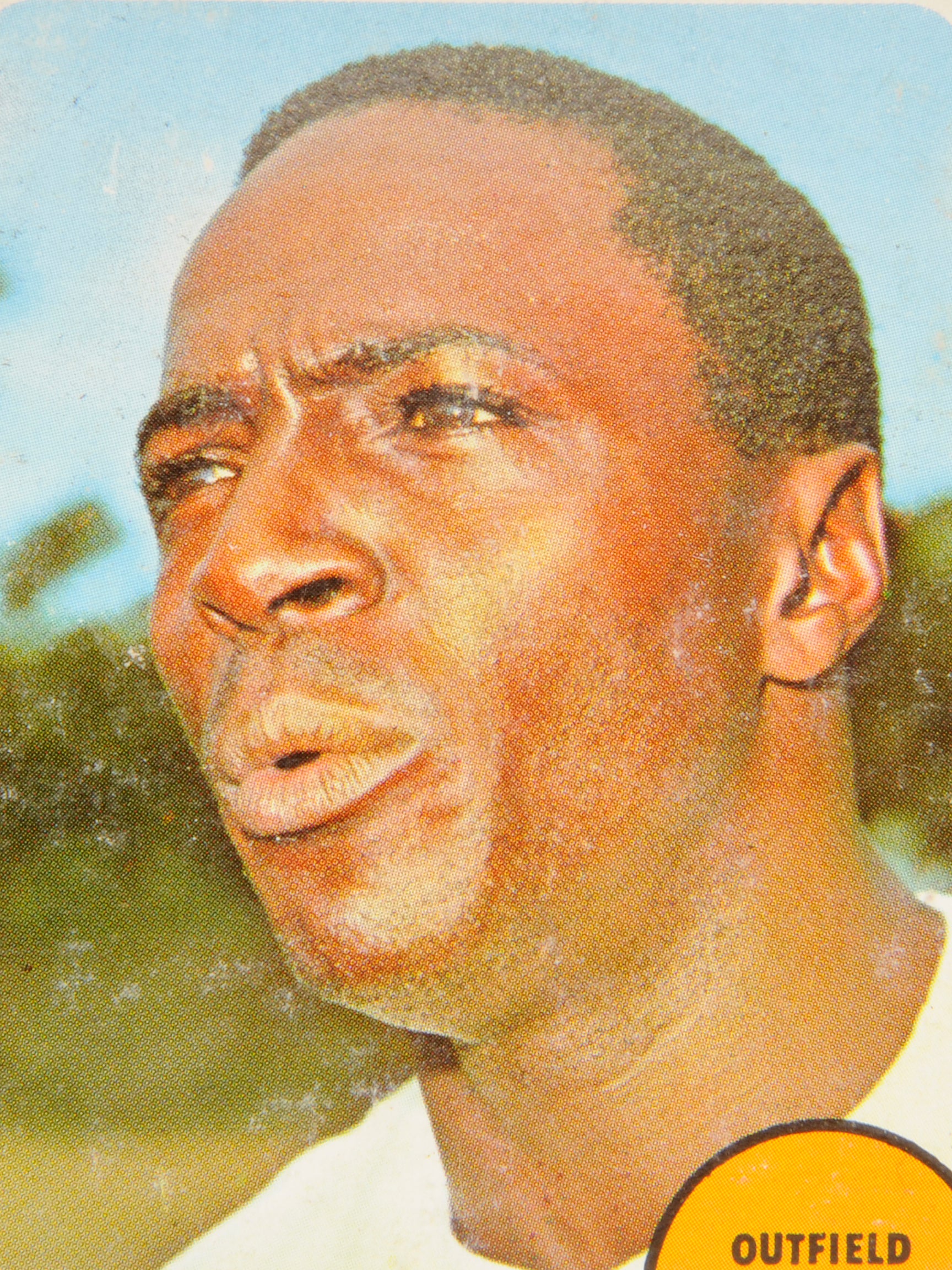

As young baseball fans, we enjoyed calling him Jim Ray Hart for two reasons. First off, Jim Ray is a cool name. By saying Jim Ray, or Jimmy Ray, that made us sound like we were part of baseball’s in-crowd. Second, it allowed us to distinguish Hart from the quarterback of the St. Louis Cardinals. He was Jim Hart, no middle name added. Of course, that Jim Hart was caucasian, while baseball’s version was African American, so there was no mistaking the two from a visual standpoint.

No offense to the Cardinals’ quarterback, but I really only cared about the Jim Hart in baseball. By then, he was near the end of his career. In the spring of 1973, a few months before this card actually came out, the Giants traded Hart to the Yankees, giving us fans in Westchester County the chance to watch him play every day. Prior to the trade, we only saw him play when the Giants played against the New York Mets. There was no MLB Network back then, no ESPN, and the Giants rarely seemed to show up on NBC’s Saturday Game of the Week.

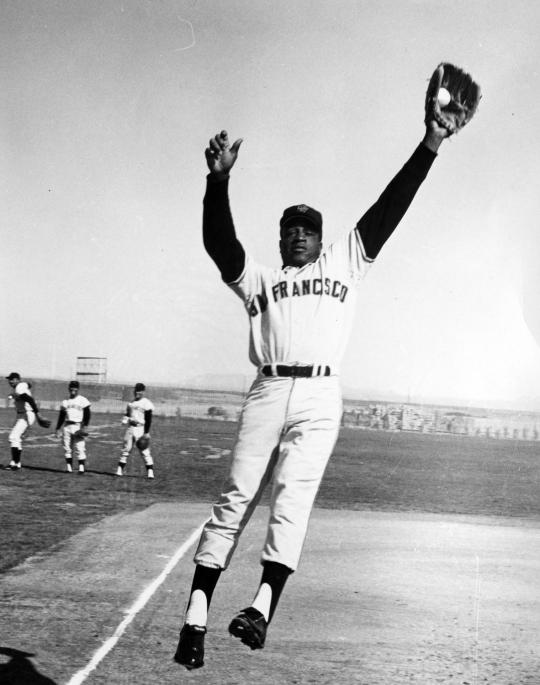

Sadly, we fans growing up in the New York metropolitan area missed out on the Hart of his prime years. But thanks to the archive at the Hall of Fame Library, we’re easily able to research his early days and learn some of the stories about a distinctive player. Right from the start, Hart made a visible impression on scouts and talent evaluators, including opposing coaches and managers. “Hart is the best hitter for his age I’ve seen in all my years in baseball,” said minor league manager Pete Reiser in a 1962 interview with the Los Angeles Times. As a manager in the Los Angeles Dodgers’ system, Reiser had seen plenty of Hart. “He’s got the quick wrists of a Hank Aaron, but still has his own style. The kid attacks the ball, and it fairly jumps off his bat.”

Less than a year later, Hart made his major league debut. Yet, that first summer with the Giants produced nothing but hardship. In only his second big league game, Hart was hit in the shoulder by a Bob Gibson fastball. The inside pitch resulted in a fractured shoulder blade. Later that season, Hart endured a Curt Simmons fastball to the head, putting him right back on the disabled list - this time for the rest of the 1963 season. Because of the incident, Hart played in only seven games of a truncated season.

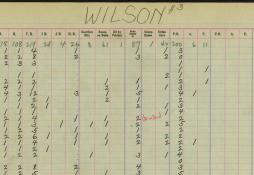

Fully recovered by 1964, Hart became the Giants’ starting third baseman. Appearing in 149 games at the hot corner, Hart put up huge numbers: 31 home runs, a .286 batting average, and an OPS of .840. Hart played so well that finished second in the National League Rookie of the Year balloting, a runner-up to Dick Allen. Hart even earned some consideration in the MVP race. The only downturn was his fielding; he committed a league-leading 34 errors at third base.

For the next four seasons, Hart remained a Giants’ stalwart. He played most of the time at third base, where he struggled defensively, but made up for his fielding with his loud bat. He also filled in as a left fielder. Along the way, he earned an All-Star Game selection and twice received votes for league MVP.

Hart also developed a reputation as the Giants’ quiet man. As longtime Giants beat writer Bob Stevens once indicated, Hart spoke fewer than 25 words a week. But he became popular with his teammates because of his easygoing nature and his willingness to laugh.

By 1969, injuries began to take a toll on Hart. Hampered by a bad shoulder, he played in only 95 games that summer. Then came a mere 76 games in 1970. It also became an open secret that Hart was a heavy drinker. His conditioning suffered, with the excess alcohol contributing to an already burly frame, pushing his weight above 200 pounds. Hart’s sharpness in the field also suffered as the result of his drinking. Instead of entering his physical prime, he was an old 27, a player with a body that was aging far too fast.

The Giants felt that Hart could no longer play third base, so they turned over that position to a colorful character named Alan Gallagher. It would have made sense to make Hart an everyday outfielder, but the Giants already had loads of talent there, from the established Willie Mays to the up-and-coming Bobby Bonds and Ken Henderson. And there were other outfielders in the pipeline, including Garry Maddox and George Foster.

In 1972, Hart hit well in limited duty, putting up a .304 batting average and an OPS of .917. But those numbers came in only 24 games and 79 at-bats. He actually spent most of the summer at Triple-A Phoenix. Hart accepted the minor league assignment because he wanted to play, and realized that if he remained in San Francisco, he would become a little-used spare part.

By early in 1973, the Giants realized that Hart was wasting away on their bench. On April 17, the Giants sold Hart’s contract to the New York Yankees for the pittance of $30,000. With the designated hitter rule now in play, the Yankees had need of a veteran hitter who could platoon with Ron Blomberg. Hart became that player.

Overweight because of a lack of action in San Francisco, Hart worked to lose some of his excess poundage. During his first month with the Yankees, Hart batted .368. He also fit in well as part of the Yankees’ clubhouse. “He’s more than a beautiful hitter. He’s a sweet person,” Ron Swoboda told Dick Young of the New York Daily News. “He fits into this team perfectly.”

It didn’t take long for Hart to acquire a nickname from his new teammates. Veteran second baseman Horace Clarke began calling him “Black Angus,” a name that probably would not have passed muster in today’s more delicate age. When asked about the nickname, Clarke tried to explain to Young. “Did you ever see one [a black angus]?” Clarke asked. “This high, and all beef,” Clarke said, motioning with his hand. “He has arms like a bull, legs like a bull. Strength like a bull.”

As well as Hart played in his first few weeks with the Yankees, he cooled off later that summer. By the end of the season, his batting average rested at only .254 with just 13 home runs. Those were certainly not great numbers, but they were better than what the Yankees likely would have received from past-their-prime veterans like Swoboda or Felipe Alou.

Unfortunately, Hart was gassed by 1974. A slow start to the new season resulted in an assignment to Triple-A Syracuse. By early June, the Yankees were convinced that Hart was done. They gave the veteran his unconditional release, even though he was still only 32 years old. Hart then caught on with the Mexican League, playing there for the next two and a half seasons before retiring.

A quiet sort, Hart left baseball for good and fell completely out of the public spotlight. I heard nothing about him until just a few years ago, when I found an article in his biographical file, which is housed in the Hall of Fame Library. The San Francisco Examiner quoted Hart about the regrets he felt about his playing career, and his heavy drinking. “If I hadn’t been drinking, I’d have played another four, five years, no problem,” Hart admitted to Larry Stone. “It got to the point I didn’t care about the game no more. What I was worrying about was the first and the 15th. That’s when the checks came in. I just wanted to go out and have a drink or two. I mean, this was every day.”

Alcoholism continued to plague Hart after his playing days. He lost his house to repossession. Shortly thereafter, he reached rock bottom when he blacked out in the middle of an airplane flight. When Hart woke up, he had no idea where he was or where he was supposed to be going. At that point, Hart realized he needed to change.

Hart went through alcohol rehabilitation and found legitimate work in a Safeway Stores warehouse before retiring in 2006. A few years later, Internet reports indicated that Hart was drinking again, in poor health, badly overweight, and living as a recluse somewhere in California. Family members were trying to reach him, but without success. The Giants invited him to a 50th anniversary reunion, but he never responded to the invitation.

Then came the news earlier this month that Hart had passed away. He died on May 19, at the age of 74.

I don’t know exactly what happened to Hart over those final years, but I suspect that his life was rough in recent years. He had apparently lost touch with family and the friends that he made in baseball.

All of this makes me a bit sad as I look at his 1973 Topps card. Hart seemed to be a good guy who was liked and accepted by his teammates.

I had hoped for a better ending for a favorite ballplayer.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame