- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1978 Topps Al Oliver

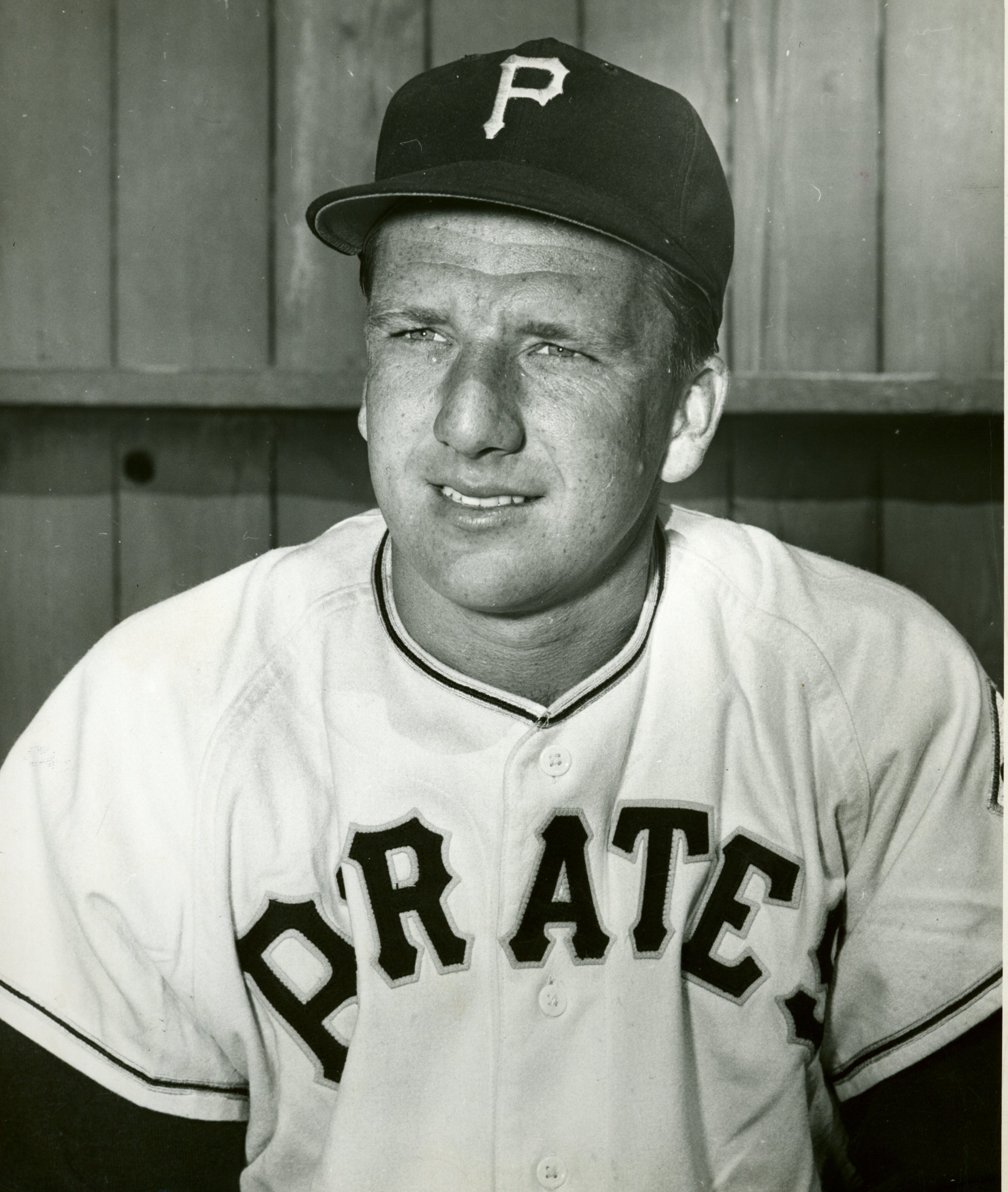

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Al Oliver

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

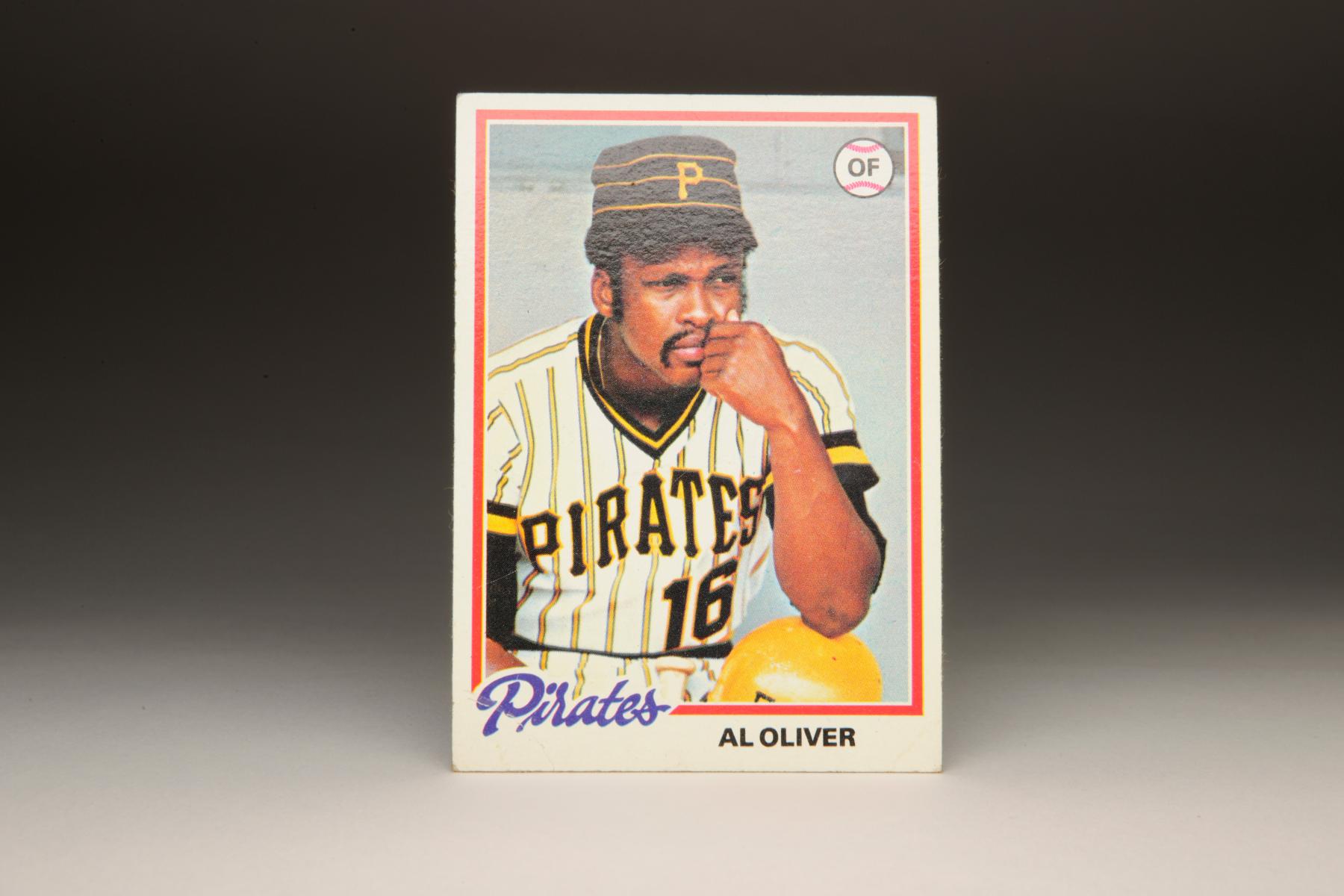

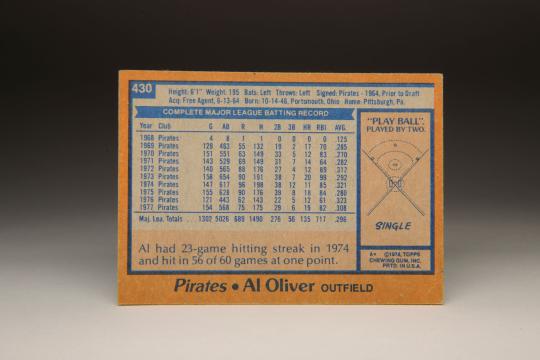

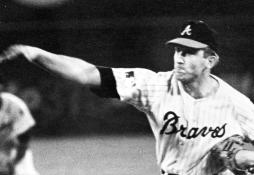

I suppose it’s possible that Al Oliver, shown wearing those distinctive Pittsburgh Pirates threads of the late 1970s, is merely striking a pose for this Topps card. The photographer from Topps may have asked him to feign a serious expression on his face, as if he were contemplating something very important. But I don’t think Oliver is acting here. It appears to me as if this is genuine. With his elbow pressed against his helmet and his left hand touching the side of his mouth, Oliver appears to be deeply engrossed in thought.

I don’t know for sure what Oliver is thinking about on his 1978 Topps card. Knowing how serious he was about the art of hitting, I can imagine Oliver taking his place in the dugout after a failed at-bat and thinking to himself, “All right, what do I need to do to come up with a hit against this guy?” After all, Oliver was a master of hitting. He went up to the plate with an idea of what he wanted to do, and how he had to combat what a pitcher was throwing to him. Yes, Oliver had great natural skills, and yes, he was an aggressive hitter (as seemingly all of those Pirates were in the late 1970s), but he was a thinking man’s hitter, too. One doesn’t compile a .303 lifetime batting average without having a plan at the plate. Having the proper mindset was part of what made Al Oliver great.

The name of Oliver triggers something in my own mindset, too. As a child of the 1970s, certain associations come to mind when I hear the name. I think of the strange character from the Brady Bunch, “Cousin Oliver,” who abruptly showed up during the final season of that innocent situation comedy in 1974. I think of former major leaguer Bob Oliver, who has already been profiled in a previous edition of Card Corner. But first and foremost, I think of Al Oliver, who was such an integral part of so many good Pirates ballclubs during the 1970s, including a world championship team in 1971.

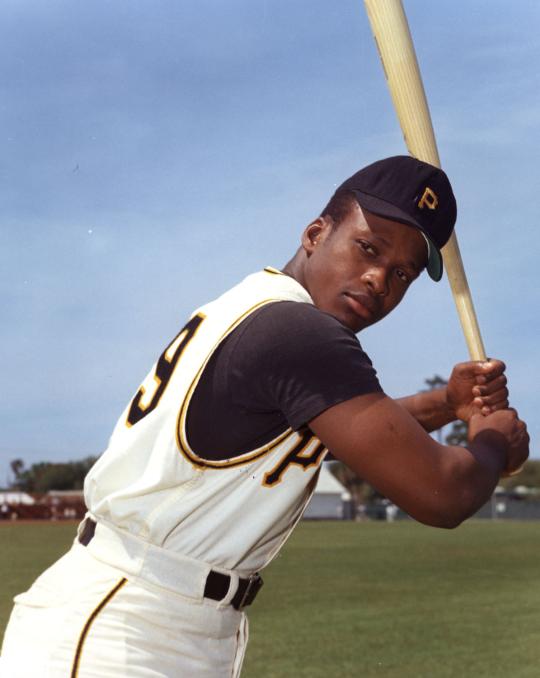

By 1978, Al “Scoop” Oliver was one of the most respected hitters in the game. His major league career started a decade earlier, when he tasted the proverbial cup of coffee with the Pirates for the first time. In 1969, Oliver moved into the Pirates’ lineup, no small feat given the talent that the organization already had playing first base and the outfield. At first base, Oliver had to compete with slugging Bob Robertson, who was billed as the “next Ralph Kiner” by some talent evaluators. In the outfield, the Pirates already had Willie Stargell in left, Roberto Clemente in right, and Matty Alou in center. That’s two future Hall of Famers and a batting champion.

As it turned out, Robertson was still a year away from refining his swing. He struggled in limited duty, opening the door for Oliver to play first base. Oliver also made 21 appearances in the outfield, called upon by manager Larry Shepard as an occasional fill-in for Stargell and Clemente. Oliver batted a solid .285 and hit 17 home runs, numbers that enabled him to finish second in the National League Rookie of the Year balloting.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

In his second full season, Oliver played even more regularly as a combination first baseman/outfielder, but both his batting average and his power numbers dipped, not an uncommon occurrence for players battling the “sophomore jinx.” He then bounced back nicely in 1971, a year that also saw him learn a new position. Having traded Alou to the St. Louis Cardinals, the Pirates needed a new center fielder. They called on Oliver, who performed admirably at the position, despite the lack of blazing speed or a cannon of an arm. Sharing time with Gene Clines, Oliver helped form a productive platoon in center field, solidifying one of the few questionable positions on what would be a championship team. When the Pirates upset the Baltimore Orioles in the World Series, Oliver earned his first and only World Series ring.

The 1971 season also provided a platform for some cultural history. On September 1, the Pirates played an otherwise forgettable game against the Philadelphia Phillies. At the time, the game received little fanfare, but became notable for the identities of the nine Pirates starters. All of them were black (either African American or Latino), marking the first time in major league history that a team had fielded an all-black starting nine.

Some players, like Oliver, didn’t realize that the Pirates were actually using an all-black lineup until the middle of the game. “I had no clue,” Oliver once told me, “Because as a rule we had at least five or six (black and Latino players) out there anyway. So, two or three more was no big thing. I didn’t know until about the third or fourth inning. Dave Cash (playing third base that day) mentioned to me, ‘Hey, Scoop, we got all brothers out here.’ You know, I thought about it, and I said, ‘We sure do!’ ” While many of the Pirates players reacted with humor, the composition of their lineup reflected the organization’s pioneering efforts at integration - unmatched in either league.

In 1972, Oliver offered his first glimpse of personal stardom. Continuing to man center field, he raised his batting average to .312, reached base 35 percent of the time and qualified for his first All-Star Game. At season’s end, the sportswriters recognized Oliver by placing him seventh in the league MVP balloting.

Oliver remained a Pirates stalwart over the next five seasons. He hit 20 home runs in 1973, batted better than .300 three times, made two All-Star teams, and received MVP votes four times. The consummate sweet-swinging left-handed hitter, Oliver had the kind of line-drive stroke that became a model for other batters. He used the entire field, swatting hard-hit balls from foul line to foul line. In his final year with the Pirates, he also made a smooth transition to left field, a position for which he was far better suited than center field.

Now 30 years old, Oliver seemed entrenched in Pittsburgh. The 1977 Pirates won 96 games, but that total was only good enough for second place in the National League East. Some within the organization believed the Pirates needed more pitching to overtake Philadelphia for the top spot. With an abundance of good hitters, some felt the Pirates could sacrifice hitting for pitching.

Oliver, who could be outspoken and critical of management, became the sacrificial lamb. Pirates general manager Harding “Pete” Peterson negotiated a complicated four-team trade with the Atlanta Braves, New York Mets, and Texas Rangers. Principally, the deal allowed the Pirates to acquire curveballing Hall of Fame right-hander Bert Blyleven from Texas. The primary cost was Oliver, who joined the Rangers as their new No. 3 hitter. So by the time that Oliver’s 1978 Topps card came out, showing him wearing the pillbox cap and gaudy colors of the Pirates, it was already out of date.

While the Rangers had mostly struggled since their relocation from Washington in 1972, they were an improving team that had won 94 games in 1977. Sure, the Texas summers were brutally hot, but the Rangers did offer the benefit of Arlington Stadium, an excellent ballpark for hitters and a place where fly balls traveled well during night games. Joining the Rangers, Oliver elevated the level of his game. A very good player in Pittsburgh, he became a full-fledged star in Texas. Over the next four seasons, he hit no worse than .309, posted OPS numbers in the .800 range, and made three All-Star teams.

Oliver reached his Rangers peak in 1980. Even though he was now 33 and seemingly at an age when most players decline, Oliver hit .319, clubbed 19 home runs, and reached a career-high with 119 RBIs. He also showed incredible durability, leading the league with 163 games played that summer.

Then came the strike-plagued season of 1981. Oliver lost his power stroke that summer, his home run total falling to four. In the meantime, his agent, Howard Mandel, tried to work out a contract extension with the Rangers. Mandel and the Rangers’ front office soon found themselves at odds - and Oliver found himself heading out of town.

The Rangers shopped Oliver aggressively in the spring of 1982. At one point, they agreed to a deal that would have sent Oliver to the New York Yankees for a package of Oscar Gamble, Bob Watson and Mike Morgan. But Gamble invoked his no-trade veto, scuttling the deal and leaving Oliver in Texas - at least temporarily. Later that spring, just before Opening Day, the Rangers traded Oliver to the Montreal Expos for a package headlined by slugging third baseman Larry Parrish.

The Expos had tried to acquire Oliver since 1977, as part of an effort to balance their right-handed heavy lineup. Now shifting to first base, Oliver found Montreal to his liking. Triumphant in his return to the National League, Oliver won the batting title with a .331 mark, while also leading the league in hits, total bases, and doubles. As a bonus, he blasted 22 home runs, establishing a career high.

Oliver would never match those numbers again, but he remained a standout hitter in 1983, batting an even .300, qualifying for another All-Star Game, and garnering some votes in the MVP race.

In 1984, the Expos decided to move in the direction of youth. That spring, they peddled Oliver to the San Francisco Giants for a package of outfielder Max Venable and right-hander Fred Breining. The trade triggered the journeyman phase of Oliver’s career. He bounced from San Francisco to Philadelphia to Los Angeles to Toronto over the next two seasons, settling into a role as a platoon player and pinch-hitter.

Unlike many fading stars, Oliver left the game on one last high note. After helping the Blue Jays clinch the American League East, he batted .375 with three RBI against the Kansas City Royals in the Championship Series. Oliver appeared to have something left to offer, but no other team expressed interest in him for 1986, at a time when major league owners were colluding against free agent players. To this day, Oliver believes that collusion ended his quest for 3,000 career hits. Instead, the skilled batsman settled for a total of 2,743 hits and a .303 lifetime batting average.

After his playing days, Oliver returned to his native Portsmouth, Ohio, where he now serves as an ambassador for the city. He joined the board of an organization called “Suicide is Not Painless,” with the hope of doing something tangible to stem the tide of teenage suicide.

A few years after becoming part of the Hall of Fame staff, I had the honor of joining Al and his former Pirates manager, Chuck Tanner, on a panel about African-American players. It was the first time I met Oliver, who impressed me with his thoughtfulness and professional but inspirational demeanor. I understood perfectly how this man had become both a deacon and a motivational speaker, a man who preached to kids the importance of avoiding drugs and other temptations.

In 2004, the Hall of Fame invited Oliver and another former Pirate, Jim “Mudcat” Grant, to participate in a celebration of Black History Month. The two former teammates spoke in the Bullpen Theater, entertaining visitors and staff with their humor, their down-home nature, and their cogent thoughts on the state of race relations in baseball.

During the talk, Oliver expressed a hope that Major League Baseball would do more to involve former players like himself and Grant in efforts to reach out to the African-American community. “I really believe that they need to bring in more players who have been there, ballplayers who have been successful,” Oliver told a mesmerized crowd in Cooperstown. “I really believe the more successful that you’ve been, the more you have to offer. The more that you’ve been around, the more that you’ve been well-traveled, like Mudcat especially. Mudcat has seen it all. I believe there’s nothing in this world that Jim ‘Mudcat’ Grant has not seen! People he’s come in contact with, things that he knows.”

Oliver also agreed with Grant about the importance of baseball connecting with the inner city, but not just with young black athletes. “Mudcat just hit on one key point when he said inner city, but let’s bring in whites. Today’s society, in the inner city, you see whites as well. And what better way can we learn about each other. See, that’s where we need to be at in 2004. This is not 1804. We should be like this now. What better way to bring people together to learn about each other, and find out that, hey, we are all in this together.”

By the end of that one-hour session in the Bullpen Theater, a thoughtful and well-spoken Al Oliver had convinced everybody that he knew even more about civil rights and race relations than he did the art of hitting.

Sometimes our baseball cards come to life in a way that is indescribable.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

More Card Corner

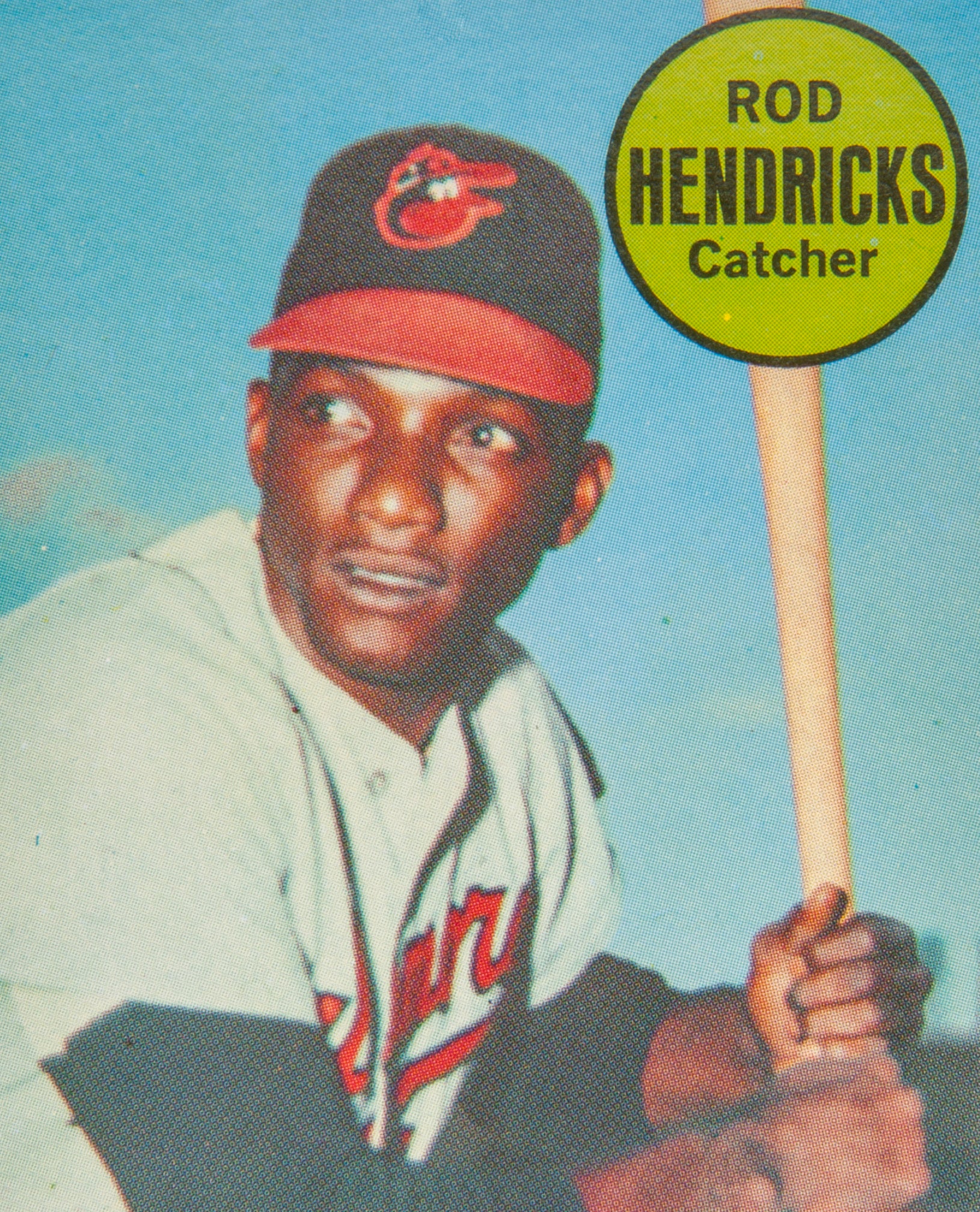

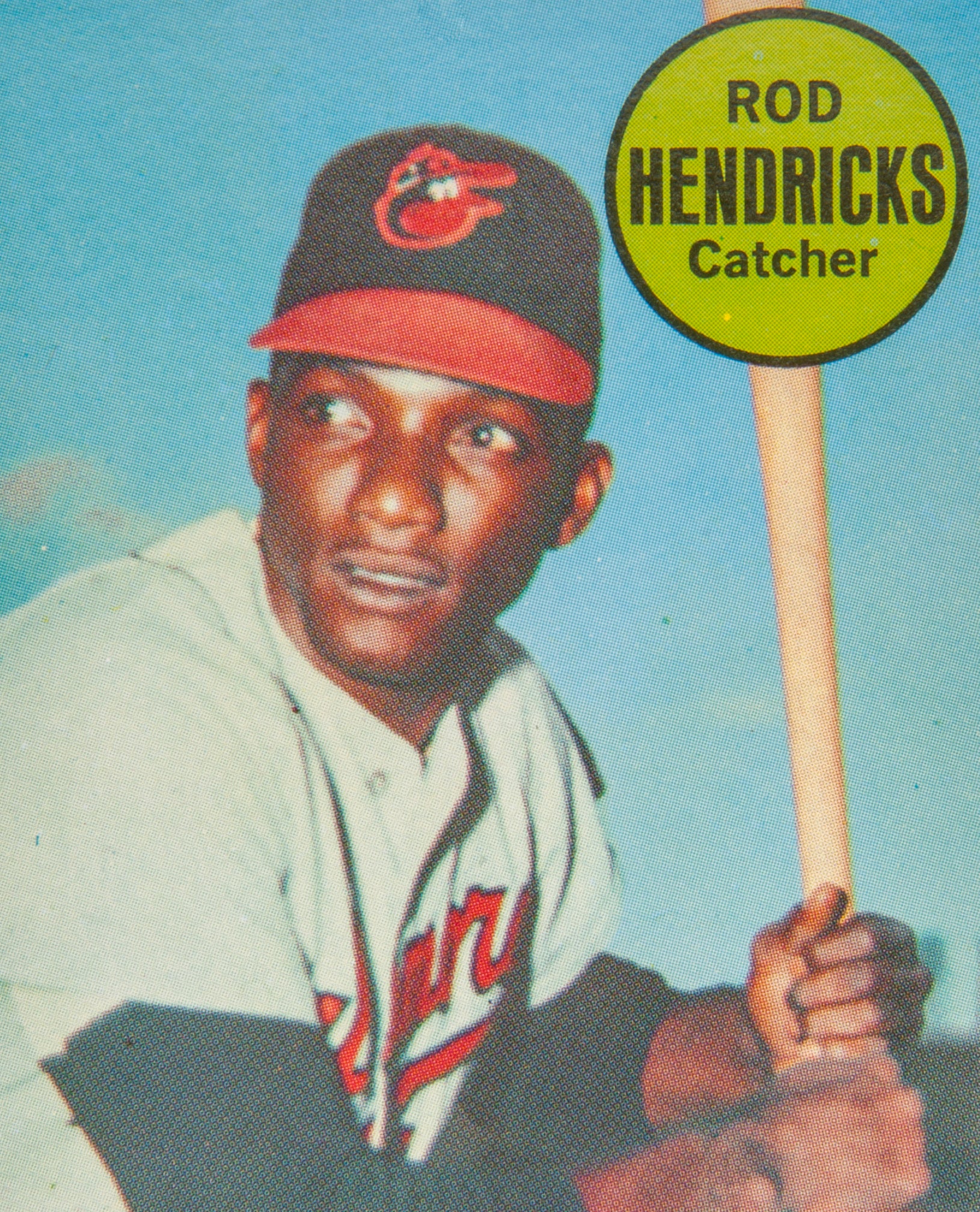

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Elrod Hendricks

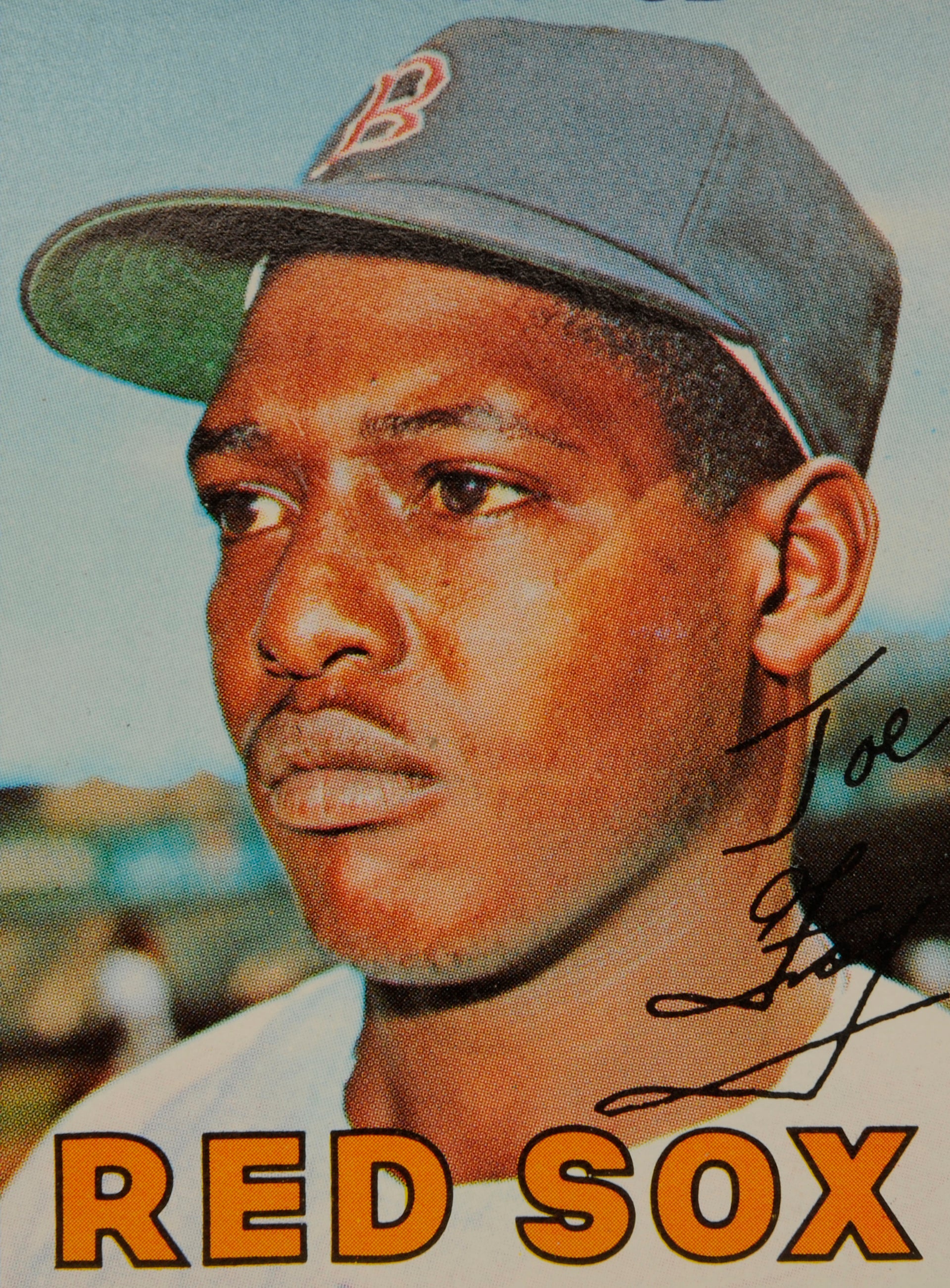

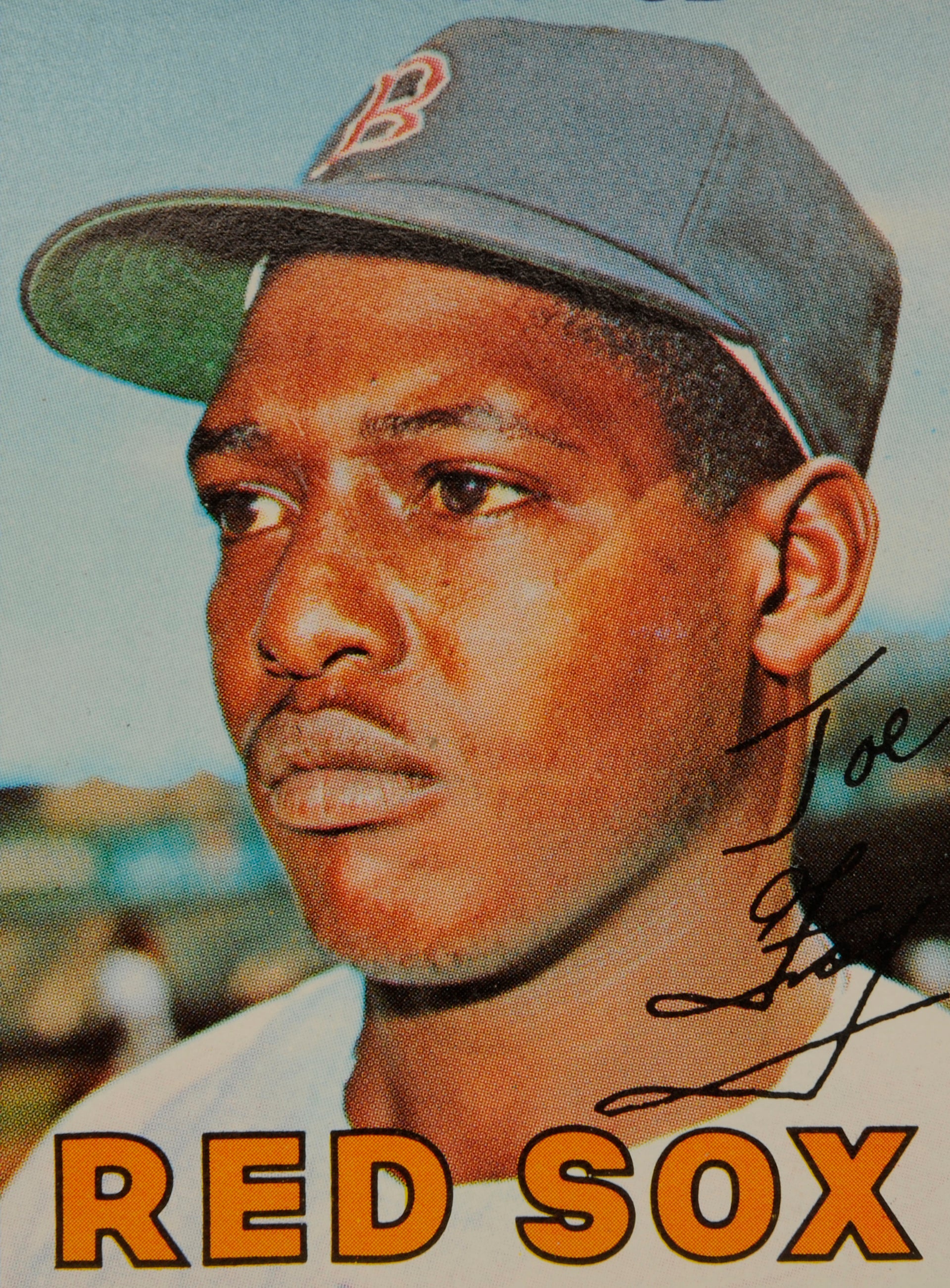

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Joe Foy

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Bob Oliver

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Elrod Hendricks

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Joe Foy

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Bob Oliver

Related Stories

Bob Gibson wills Cardinals to Game 7 victory in 1964 World Series

Mrs. America and the AAGPBL

Unforgettable: Four Newest Hall of Famers Inducted

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Hickman

Phil Niekro elected to Hall of Fame

Jeff Bagwell, Tim Raines, Iván Rodríguez Elected to Hall of Fame by Baseball Writers’ Association of America

Umpires Break Through Glass Ceiling

Hall of Fame Celebrates World Series Weekend, Honoring San Francisco Giants, Aug. 1-2 in Cooperstown

Rickey Henderson’s two RBI lead A’s to 11th straight win to start 1981 season

Ten Named To Golden Era Ballot for Baseball Hall of Fame Election

01.01.2023

Ten Named To Golden Era Ballot for Baseball Hall of Fame Election

01.01.2023