- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1985 Topps Cliff Johnson

#CardCorner: 1985 Topps Cliff Johnson

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

If you watch baseball today, you will inevitably notice the way that the majority of hitters swing the bat. They execute each swing with a large degree of ferociousness and a decidedly uppercut finish. It’s all about launch angles, exit velocity, and long, long home runs. The two-strike, defensive swing has become, for most hitters, a thing of the past.

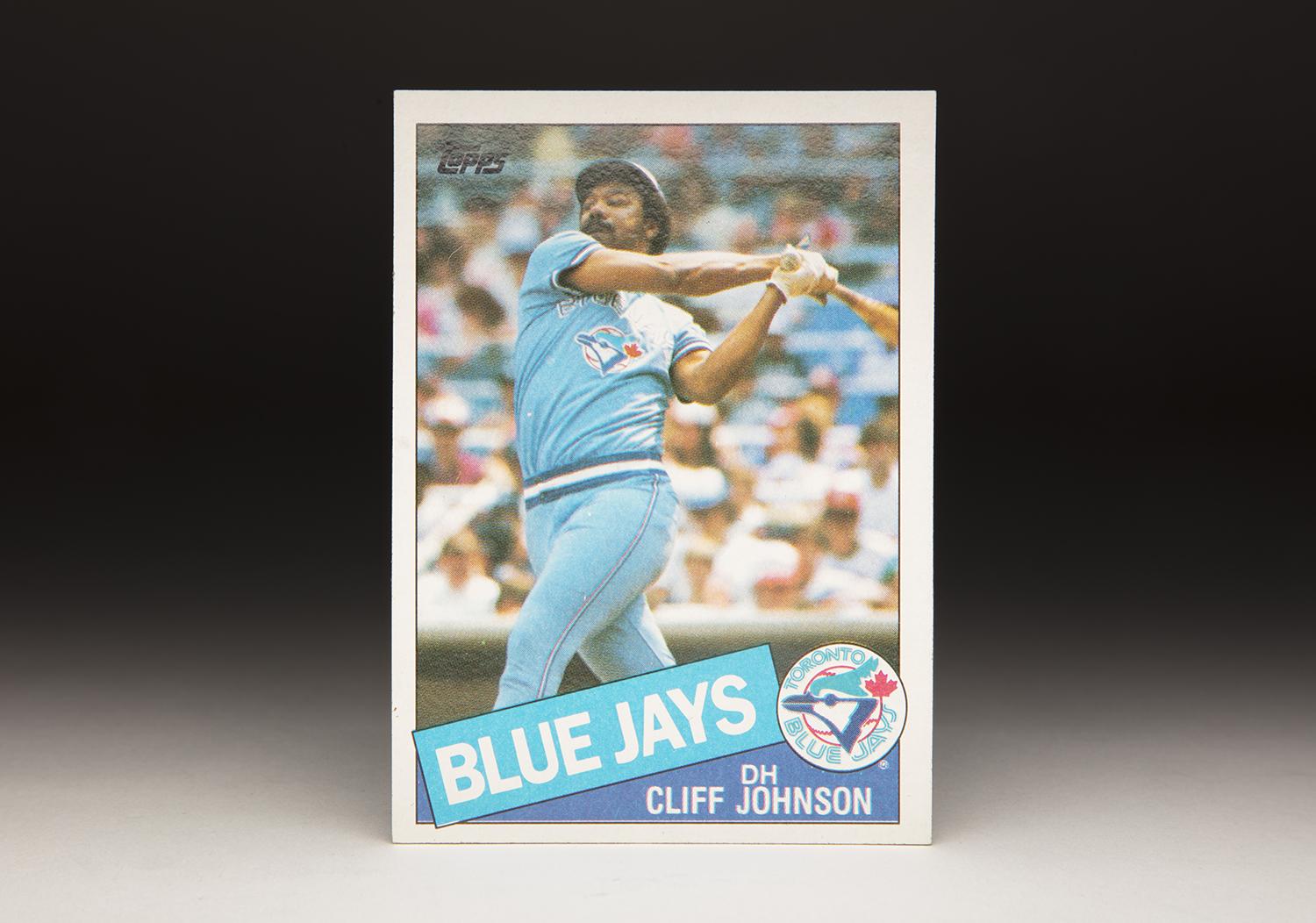

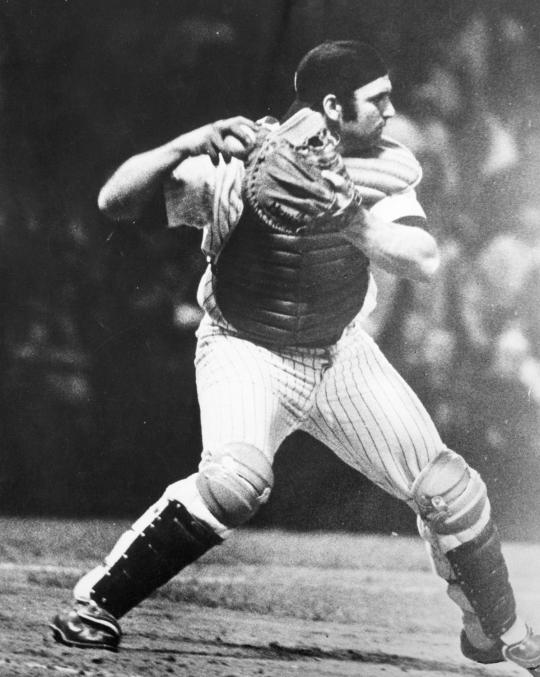

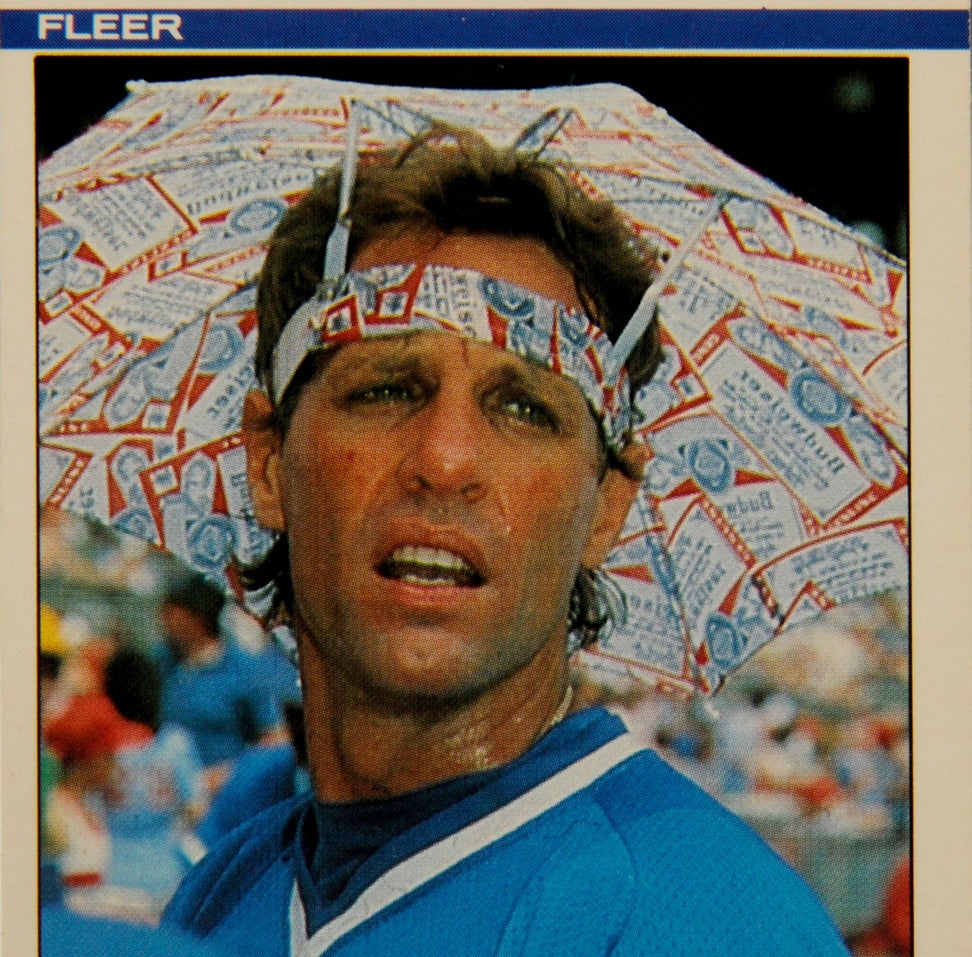

Cliff Johnson embodied the 2017 hitting philosophy more than 30 years ago. Just one look at his 1985 Topps card reveals the violent nature of Johnson’s swing, the torque exerted by his upper body, and the extreme uppercut conclusion. There is no way to know if this swing by Johnson produced a home run, but based on his body language, and the direction in which he appears to be looking (toward the outfield), it would not be outlandish to think that the ball ended up over the outfield wall. After all, Johnson hit 16 home runs during the 1984 season, 13 of them coming on the road.

There’s more material of note with regard to Johnson’s card. It shows him sporting the powder blue road uniform of the Toronto Blue Jays, his team for all of 1984. But Johnson actually started the 1985 season with the Texas Rangers, who had acquired him as a free agent over the winter. Later in 1985, Topps came out with a “traded” card for Johnson. Ironically, that card would soon turn out to be somewhat obsolete. In August of ’85, the Rangers sent Johnson back to Toronto in a trade for three minor league players. Topps simply could not keep up with Johnson’s many movements.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

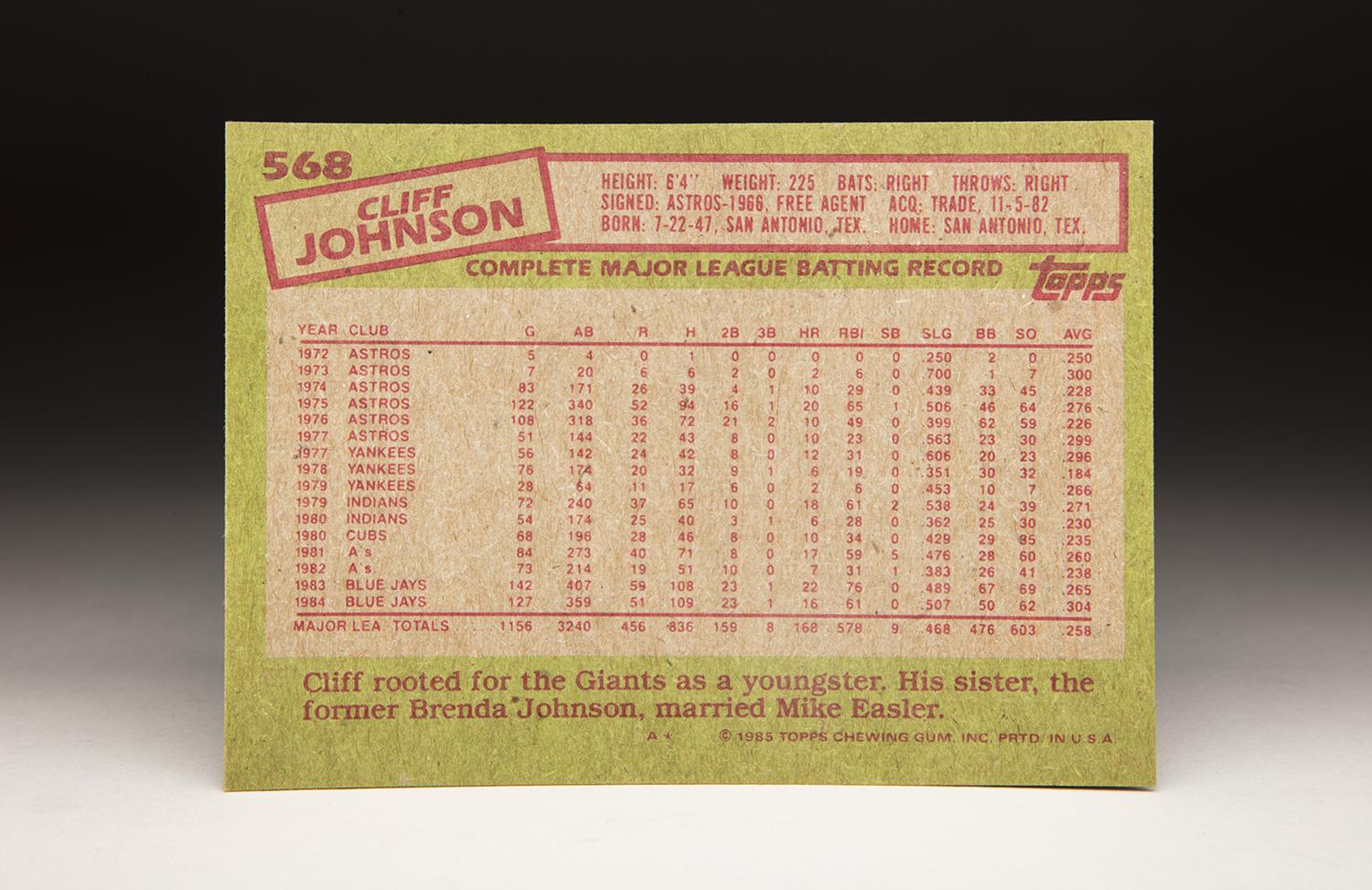

Johnson’s well-traveled career as a power hitting catcher began two decades earlier, when the Houston Astros made him their fifth-round draft choice out of Wheatley High School in San Antonio, Texas. Johnson did not exactly take pro ball by storm; he hit only .170 in the Florida Instructional League and actually spent some time playing for the affiliate of the Cincinnati Reds. (Back in the 1960s, it was common for teams to loan out players to other organizations, often as a way of ensuring that they could receive needed playing time.) In 1967, Johnson played Class A and Rookie Ball, once again spending some time on loan, this time to the old Washington Senators’ organization. The loan arrangement with the Senators continued in 1968, with Johnson showing steady improvement as a hitter.

From 1969 to 1972, Johnson alternated productive minor league seasons with off years. Bouncing back in ’72, he hit well enough to merit a September call-up to Houston, his first taste of the majors after seven seasons in minor league ball. He hit .250 in five late-season games, but then returned to the minor leagues for most of 1973. After dominating the American Association and clubbing 33 home runs, he received another September call-up, impressing with a .300 average and two home runs in seven games.

By 1974, the Astros were ready to make a commitment to Johnson. They kept him on the roster the entire season, using him as a platoon catcher with lefty-swinging Milt May and as an occasional first baseman. Johnson showed his expected power, hitting 10 home runs in 171 at-bats and slugging a respectable .439. Johnson’s numbers took on an even more impressive connotation because of his home ballpark; the Houston Astrodome, with its long outfield dimensions and stale indoor air, seemed to suppress the distance of potential home runs.

Cliff Johnson embodied the 2017 hitting philosophy more than 30 years ago. His 1985 Topps card, pictured above, reveals the violent nature of Johnson’s swing, the torque exerted by his upper body and the extreme uppercut conclusion. (Milo Stewart Jr. / National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

In 1975, Johnson played more often, appearing in 122 games as a first baseman, catcher, and left fielder. Johnson wanted to play every day, but ideally as a first baseman or outfielder. He didn’t particularly like to catch. Furthermore, his catching skills fell short of what the Astros wanted. At six-four and 240 pounds, Johnson lacked dexterity and sometimes struggled in blocking pitches. He also had trouble throwing out baserunners. But the Astros did their best to find a place for him in the lineup, knowing that he had as much raw power as any player on the team. In fact, Johnson led the Astros with 20 home runs, despite playing fewer games than power-hitting teammates like Bob Watson, Doug Rader and Cesar Cedeno.

Prior to the 1976 season, the Astros announced that they planned to make Johnson their everyday catcher, at least at the start of Spring Training. “He is a major league hitter,” manager Bill Virdon told Harry Shattuck, corresponding for the Sporting News. “When we go to Spring Training, Cliff will be the No. 1 catcher. One of my main jobs will be to convince Cliff that he should want to catch.”

The plan to have Johnson handle the bulk of the catching never materialized. Instead, his superutility role continued in 1976, and his playing time actually decreased because of a drop in his batting average, which fell to .226. After the season, the Astros made a trade for another right-handed hitting catcher, Joe Ferguson, a foreboding sign that Johnson might soon become expendable. Still, Johnson started the 1977 season with the Astros and hit well, putting up a .299 average and 10 home runs through 51 games. Because of the presence of Ferguson behind the plate and Watson at first base, Johnson saw most of his playing time in left field. Given his lack of footspeed and agility, and the amount of territory that needed to be covered at the Astrodome, left field was simply not an ideal fit for Johnson.

Not surprisingly, trade rumors began to circle around Johnson, whose bat made him a desired commodity. Sure enough, at the June 15 trading deadline, a deal took place. The Astros sent Johnson to the New York Yankees for a package of three minor leaguers, including prized young first baseman Dave Bergman.

For much of the early 1970s, the Yankees had tried to acquire right-handed hitting to balance a lineup that leaned heavily leftward. In 1973, they purchased Jim Ray Hart, who lasted parts of two seasons as a DH before it became obvious that he was no longer a prime player. In 1974, the Yankees acquired switch-hitting catcher/infielder Bill Sudakis from the Texas Rangers; he would become best known for brawling with teammate Lou Piniella during a road trip in Milwaukee. The Yankees later tried Walt “No Neck” Williams, Alex Johnson, and Bob Oliver, but all of those players had seen their best days.

The Yankees’ search for righty hitting had continued in the spring of ’76, when they gave veteran Tommy Davis a tryout, but he failed to make the Opening Day roster. Then came Cesar Tovar, a favorite of manager Billy Martin, but his hitting skills had abandoned him. In 1977, the Yankees appeared to have found a solution when they signed “The Toy Cannon,” the underrated Jimmy Wynn. But he hit only .177 and quickly received his release.

Still searching for a right-handed hitter in June of 1977, the Yankees completed the deal for Johnson. He actually filled two needs for the Yankees, giving them both a right-handed slugger and a quality backup catcher for their overworked starter, Thurman Munson.

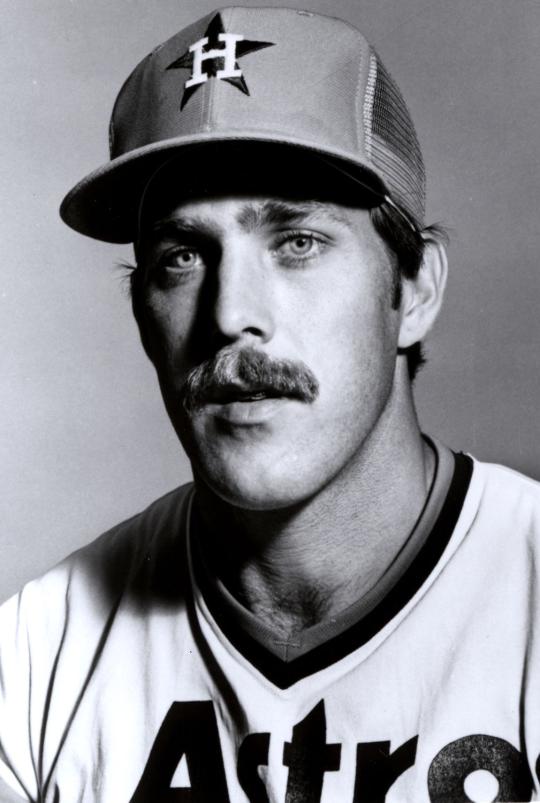

Johnson did what Hart, Sudakis, Oliver, Wynn, and the others could not do. In one memorable game against Toronto, Johnson belted three home runs. For the season, he batted .296 with 12 home runs in 142 at-bats for the Yankees. More significantly, he slugged .606 and compiled a .405 on-base percentage. When the Yankees faced a left-hander, Martin wisely found a place for Johnson to play, either at first base, catcher, or DH. Granted, Johnson wasn’t much of a catcher, but he could play the position in short doses. Most critically, Johnson swung the bat with ferocity, showed a patient eye at the plate, and performed better than any backup catcher the Yankees had featured since the days of Johnny Blanchard.

Not only did Johnson become an important part of the Yankees’ second-half surge that summer, but he also devoured the Kansas City Royals’ pitching staff in the Championship Series. In 16 at-bats, Johnson delivered six hits, including a home run, and slugged a remarkable .733, helping the Yankees to a wild, five-game win over the Royals. The Yankees then went on to win the World Series, cementing Johnson’s place as one of the better acquisitions in the history of the June 15 trading deadline.

Johnson also became a fun subject in the Bronx. On Yankee broadcasts, longtime announcer Phil Rizzuto regularly referred to Johnson as “Heathcliff,” which seemed like an especially cool name. I always assumed that was his real first name, but it is not; it is actually Clifford. Other folks in baseball referred to him as “Topcat,” for reasons that remain unknown to me. Whatever the reason for the nickname, Johnson’s hitting made him a “cool cat” in New York.

Everything went right for Johnson in 1977. And then, in 1978, the bottom fell out of his game. Losing his stroke at the plate, Johnson batted .184 with only six home runs in 174 at-bats. He became a virtual nonentity in the postseason, going hitless in three at-bats against the Royals and Los Angeles Dodgers.

Then came the extremely difficult season of 1979. During spring training, Johnson expressed frustration over his role as a backup catcher. “Hey, nothing against Thurman, he’s great,” Johnson said during a colorful interview with Phil Pepe of the New York Daily News. “And as long as that man [Munson] is here, he’s going to be No. 1, and he should be. My trouble is I don’t have a big name. There aren’t enough alphabets in my name. And in baseball, big money does to little money what ‘Wimpy’ does to hamburgers. Big money eats up little money.”

Johnson’s situation only worsened in late April, when he took offense to some playful ribbing from teammate Goose Gossage and gave the Yankees’ relief ace a slap of his hand. That led to a full-scale wrestling match. Johnson escaped unharmed, but when Gossage shoved Johnson, he tore a ligament in his pitching thumb. The Goose would miss the next three months of the 1979 season, which turned into a disaster for the Yankees, culminating in the tragic loss of Munson in a plane crash on Aug. 2.

Johnson’s clubhouse incident essentially ended his career with the Yankees. Within two months, he was gone – shipped off to the Cleveland Indians in a deal for middle reliever Don Hood.

Given a fresh start in Cleveland, Johnson initially did well for his new team. The Indians made him their regular DH and watched him hit .271 with 18 home runs over the second half of the season. Johnson also endured a painful reunion with the Yankees. On Sept. 25, Johnson and the Indians hosted the Yankees in a game at Municipal Stadium in Cleveland. Yankees right-hander Bob Kammeyer, acting on orders from manager Billy Martin, drilled Johnson in the left arm with his fastball. Knowing full well that the inside pitch was intentional, Johnson shouted at Kammeyer, “I know you got better control than that!” After the game, according to eyewitness reports from several Yankee players, Kammeyer received a $100 “bonus” from Martin.

Johnson did not appreciate the attempt at revenge, but otherwise seemed comfortable in Cleveland. The Indians hoped that he would continue his productive hitting in 1980, but Johnson slumped, his batting average sinking to .230. So on June 23, the Indians made a waiver deal, sending Heathcliff to the Chicago Cubs for minor league outfielder Karl Pagel.

The return to the National League removed the DH option for Johnson, while also separating him from further reunions with the Yanks. The move to Chicago also gave him a chance to play at Wrigley Field. Over the balance of the season, Johnson hit 10 home runs and slugged .429, as the Cubs used him as a first baseman against left-handed pitching, while also giving him some time in left field and at catcher.

Johnson played decently for the Cubs, but they had expected stronger hitting from him, particularly at Wrigley Field. After the season, the Cubs dealt him to the Oakland A’s for minor league left-hander Mike King. It marked Johnson’s third trade in the last year and a half. Now back in the American League, Johnson returned to the DH role for which he was best suited, hit 17 home runs, and posted an OPS of .805. But then came another off year in 1982, prompting yet another trade, this time to the Blue Jays for backup outfielder Alvis Woods.

The Blue Jays became a perfect fit for Johnson. He put in two productive seasons as the Jays’ regular DH and continued to add to his reputation as an excellent pinch-hitter. While with Toronto, he hit his 19th career pinch-hit home run, breaking the all-time record held by Jerry Lynch. He also became a fan favorite at Exhibition Stadium, where the Jays played their home games in the 1980s.

After his short tenure in Texas, which included a midseason knee operation, Johnson returned to the Blue Jays and proceeded to hit well over the next year and a half. Even at age 39, he continued to put up good power numbers, but decided to call it quits at the end of the 1986 season.

Since his retirement, Johnson has mostly worked outside of baseball, but has still maintained a tie to the game. He has also shown an interest in the history of baseball. A number of years ago, he paid a visit to the Hall of Fame’s Giamatti Research Center, where he spent several hours combing through the Museum’s library that features more than three million documents.

Thankfully, Johnson has also reconciled with the Yankee organization, which regularly invites him to Old-Timers’ Day reunions at Yankee Stadium. For old Yankee fans who remember the 1970s, the chance to see Johnson, a member of the 1977 and ’78 world championship teams, is always a welcome sight. Even at an older age, Johnson has shown remarkable power, reaching the seats with a long home run in the 2001 Old-Timers’ Day gathering. And who delivered that pitch? Goose Gossage, of course.

Even in retirement, Johnson has continued to swing the bat hard. If he was a bit younger, perhaps about 30 years younger, he would fit in quite nicely with the way that baseball is played in 2017.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame