- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1972 Topps Dave Cash

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Dave Cash

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

So where did it all begin, this strange and consuming obsession with baseball cards? I suppose every collector has a story of origin. For me, it unquestionably began during the spring of 1972. I lived on the border of Yonkers and Bronxville, NY. (The latter town was the home of Hall of Famer Ford Frick, but he never invited us over for dinner). It took about 15 minutes to walk from my house into the village of Bronxville, a small town of about 6,000 residents. On a sunny Saturday morning, I made that trek, with the expressed purpose of stopping at Gillard’s Stationery Store, which was located right on the main drag in the village.

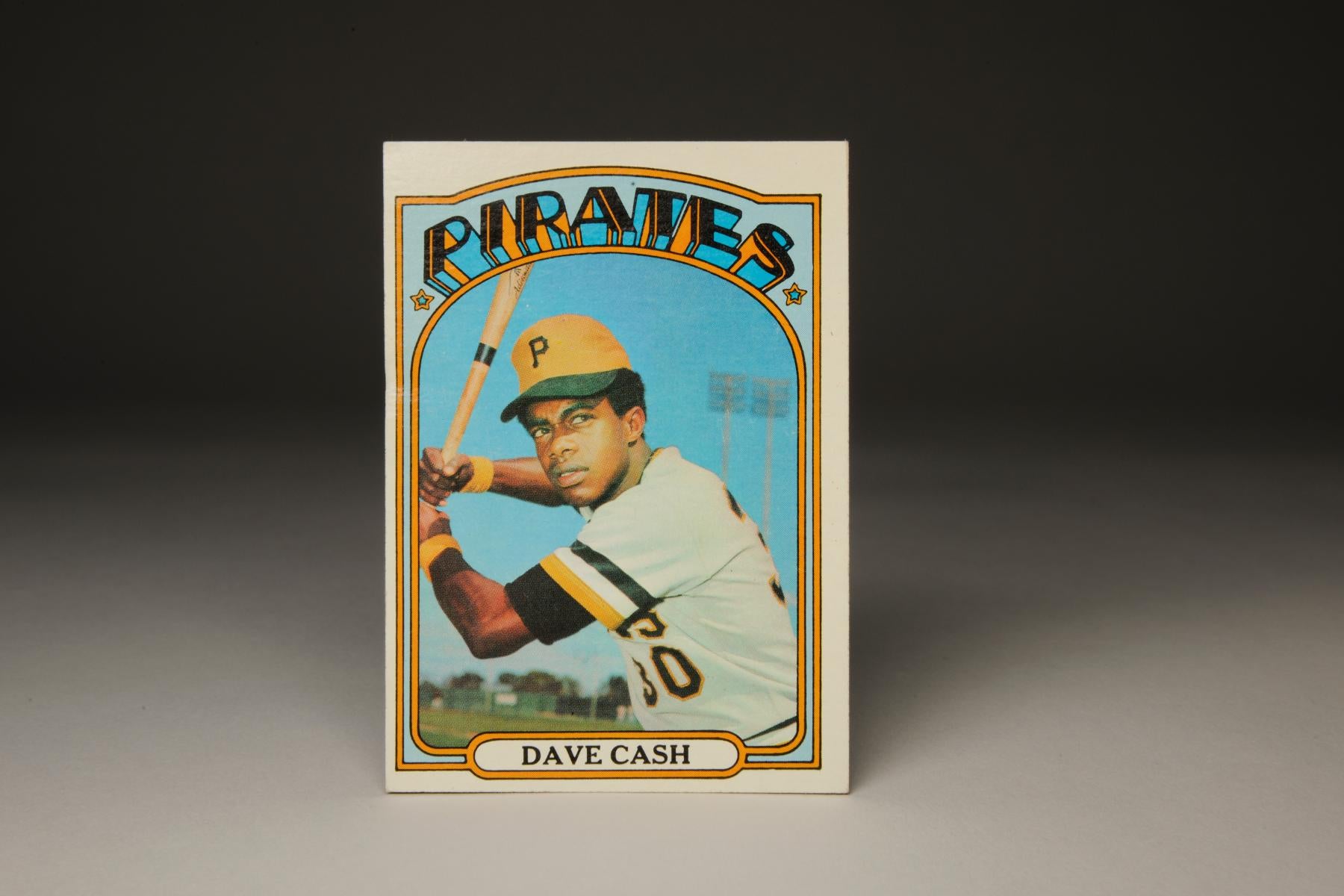

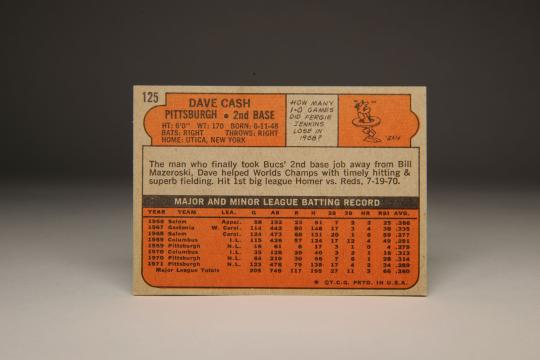

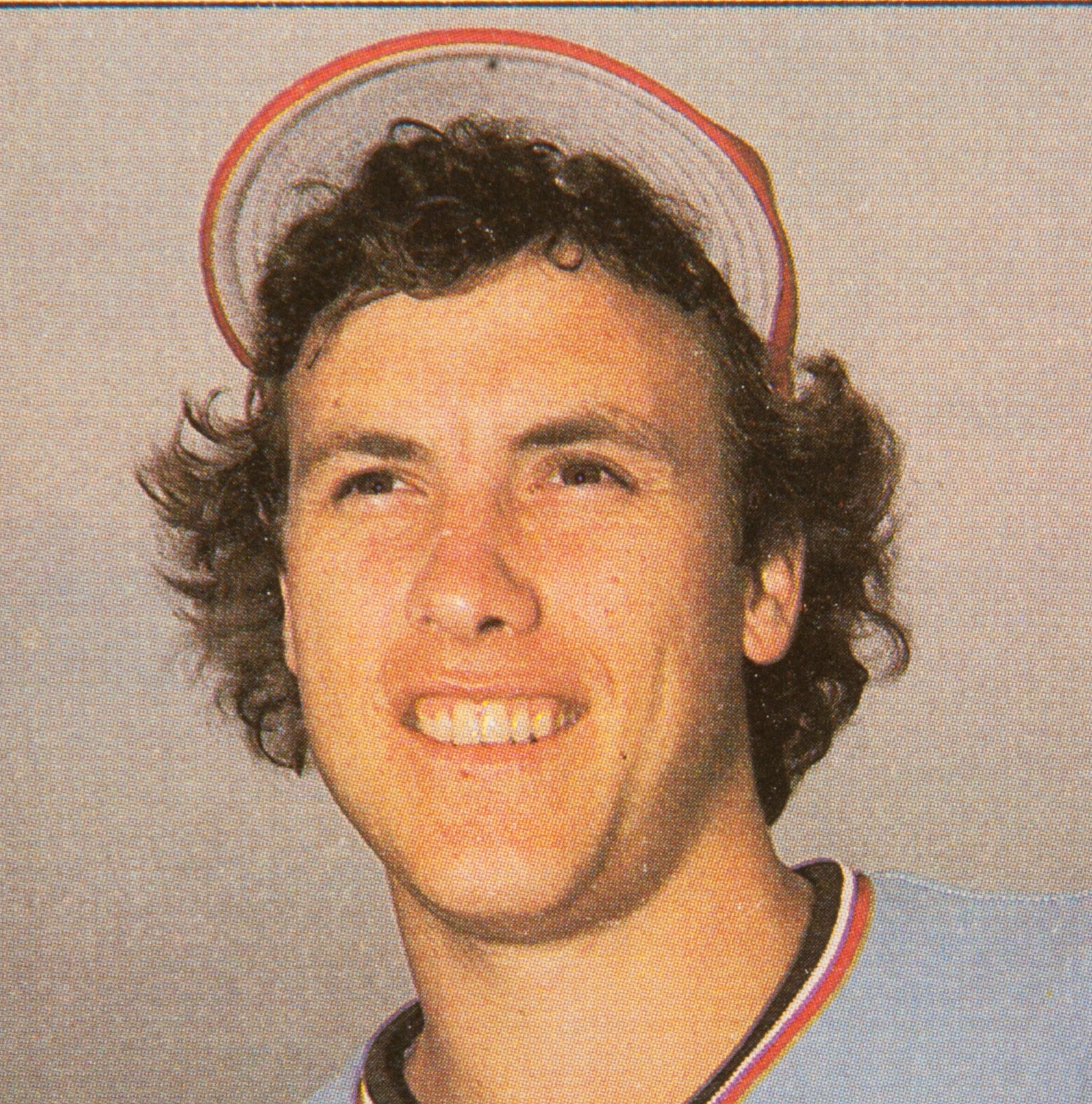

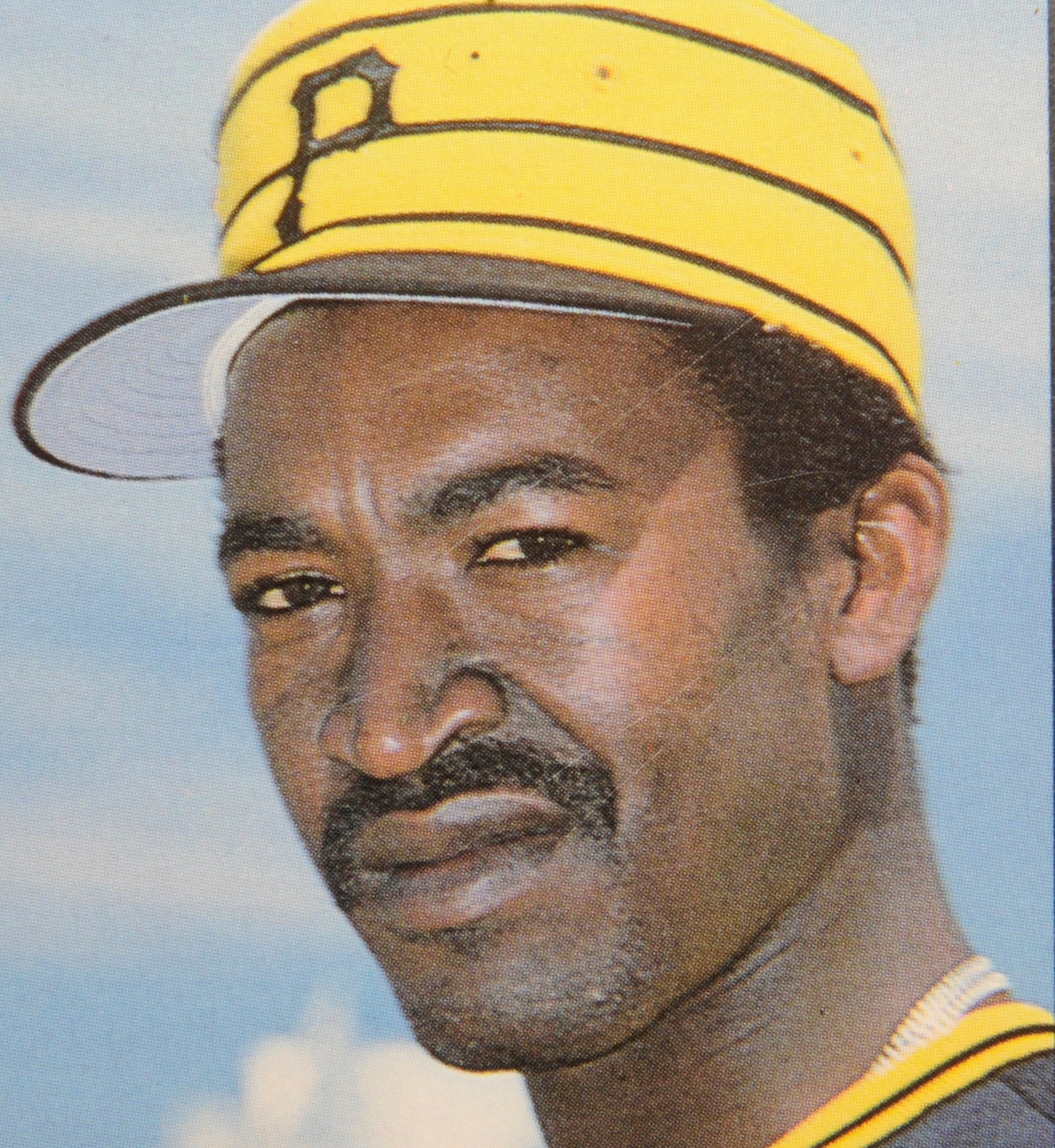

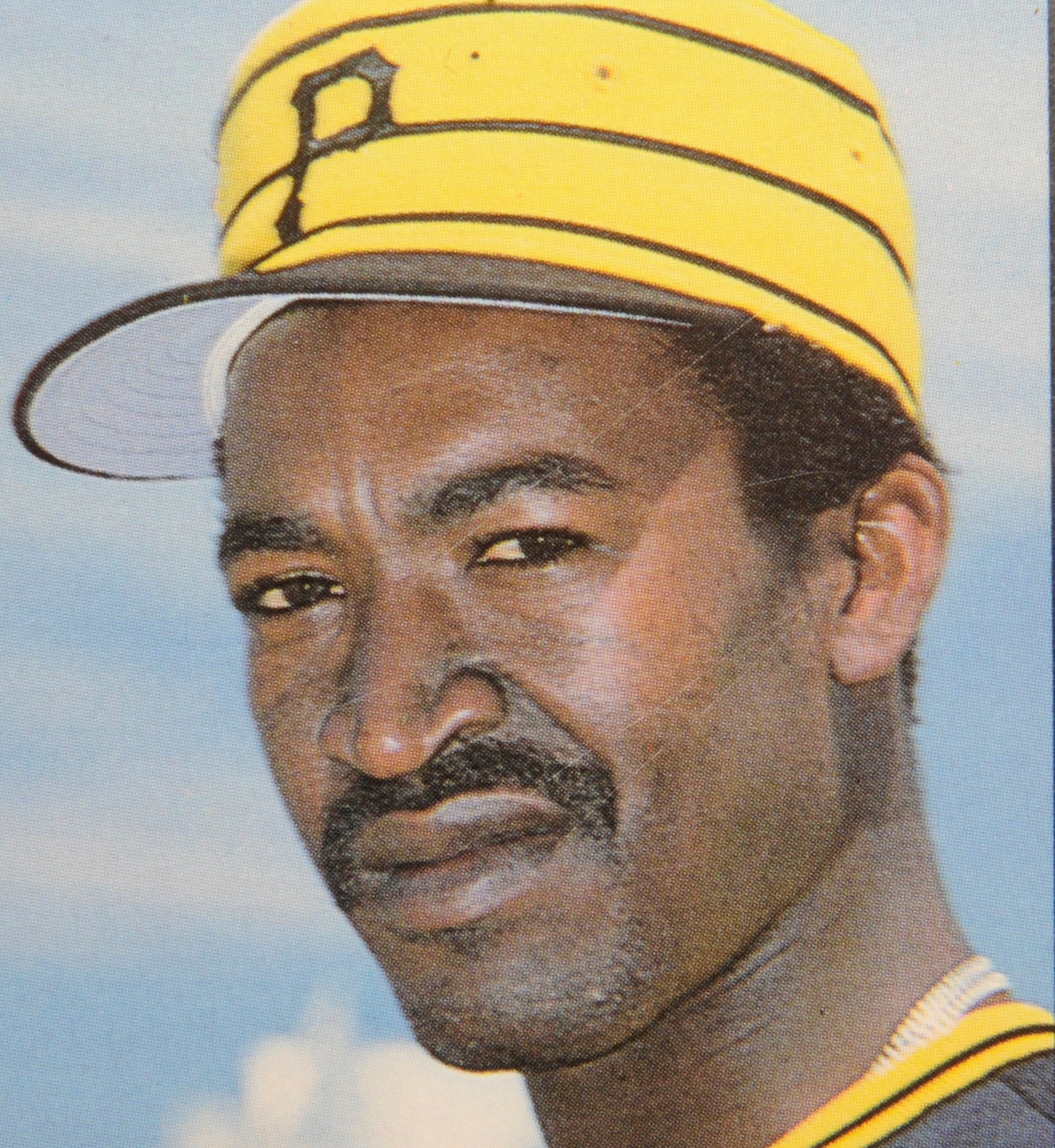

As you entered the village, Gillard’s was just about the first store that you would hit. It was an old-fashioned stationary store that sold newspapers, greeting cards, monster magazines, and yes, baseball cards. On this trip into Gillard’s, carrying my own money, I was interested in purchasing the latter item. It was at Gillard’s that I purchased my first pack of cards. I remember distinctly the top card in the pack: It was a 1972 Dave Cash, No. 125 in the set. Since the Cash card happened to be on top, and was therefore the first card that I saw, I have dubbed it the first card in my collection.

There were a few other notable cards in that pack, like the final Topps card for Jim “Mudcat” Grant (who would later become a frequent visitor to Cooperstown), but the Cash card was the one that stood out above the rest. On its surface, the card is relatively simple. It’s a classic posed batting shot, with Cash set against the blue sky background, complete with the Spring Training light towers off the upper right-hand corner of the frame. With serious intent evident on his face, Cash is gripping the bat for the Topps photographer. Cash looks so serious that it seems like he’s almost a little annoyed, which I figured could be attributable to the difficult and important business of trying to hit a baseball. In the back of my mind, I wondered whether Cash was somewhat of an unpleasant guy, someone not be trifled with, either by opposing pitchers or baseball card photographers. As impressionable youngsters, it’s rather remarkable to consider what goes through our minds.

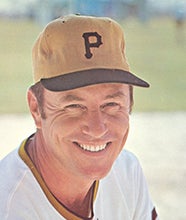

From the standpoint of baseball, the ’72 Cash was a good card to have. After all, he was the starting second baseman for the defending World Champion Pittsburgh Pirates, a team that I liked, but also the team that had stunned just about every veteran observer of the game by upsetting the Baltimore Orioles in a tremendously entertaining World Series the previous fall.

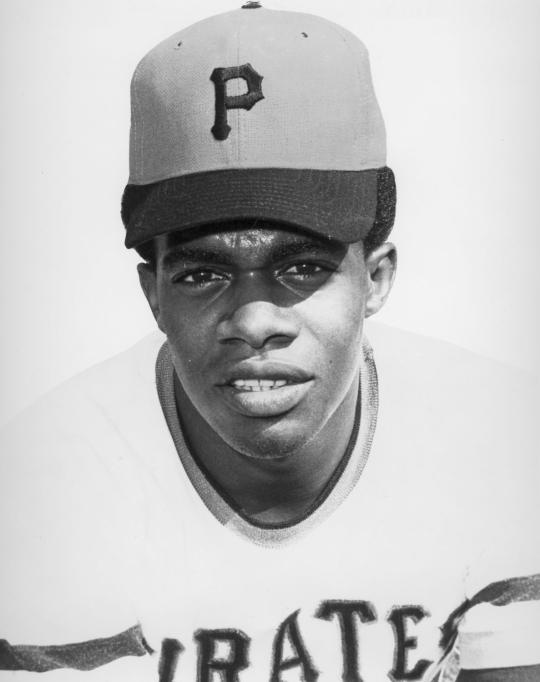

I knew a little bit about Cash at the time, but I would learn much more as my fandom progressed. From an early age, he idolized Jackie Robinson, who starred for the Brooklyn Dodgers during Cash’s early youth. Cash grew up in Utica, NY, hardly a hotbed for baseball given the long winters, but he nonetheless starred in football, basketball, and baseball at Proctor High School. Cash’s basketball talents drew the attention of Syracuse University, which recruited him, but his high school grades lagged behind the requirements of the Orangemen. Without a basketball scholarship in hand, Cash pursued baseball fulltime. That decision began to pay off in 1966, when the Pirates made him their fifth-round choice in the MLB Draft.

The Pirates switched Cash from shortstop to second base and watched him move up steadily through their minor league system, earning his first call-up to Pittsburgh in September of 1969. He hit a respectable .279 in 18 games, giving the Pirates hope that they had found the successor to their aging future Hall of Fame second baseman, Bill Mazeroski.

By 1971, Cash had succeeded Mazeroski. To his credit, Maz did his best to help Cash, giving him advice about handling the position and turning the double play. Helped greatly by the man whose job he was taking, Cash began to blossom. Hitting from gap to gap, he batted a solid .289 as the Pirates’ primary second baseman in 1971, while also filling in at third base and shortstop. At the plate, he collected more walks than strikeouts; in the field, he showed range and athleticism. Though overshadowed by great teammates like Roberto Clemente and Willie Stargell, Cash played his role in helping the Bucs win their first title since 1960.

The free-swinging Cash continued to hit and field well over the next two seasons, but his commitment to the Army reserves clearly affected his development. Because of his military duty, which usually fell on several weekends each summer, Cash had to miss significant stretches of playing time. One time Cash missed 15 consecutive days.

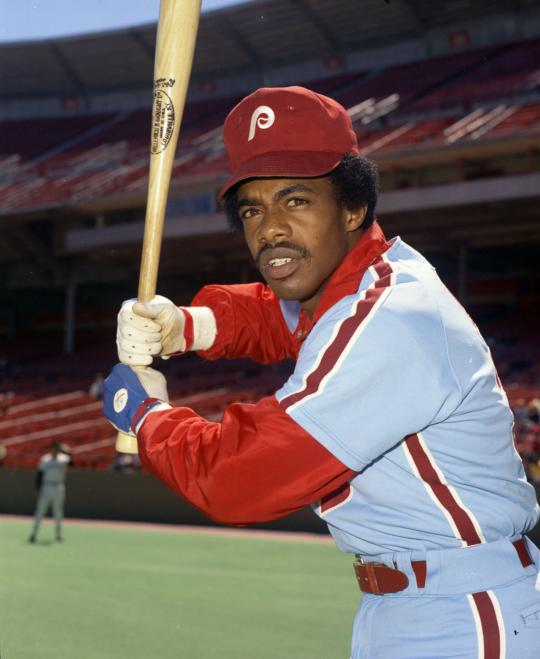

The Pirates also had a glut of young second baseman, with Rennie Stennett already on board and a youthful Willie Randolph in the pipeline. So after the 1973 season, the Pirates deemed Cash expendable, sending him to the Philadelphia Phillies for left-hander Ken Brett.

While Cash had played well for Pittsburgh, he flourished in Philadelphia. Durable and dependable, he missed only two games over the next three seasons, hit better than .300 twice, and made three consecutive All-Star teams. With Cash and Larry Bowa solidifying the middle infield, the Phillies won three straight National League East titles. In terms of intangibles, Cash provided leadership and counsel to his teammates, helping to calm down the mercurial Bowa and encouraging a young Mike Schmidt at third base.

The end of the 1976 season saw the arrival of free agency in baseball. Among those who benefited from the first class of free agency was Cash. The Montreal Expos came up with the best offer, signing Cash to a five-year contract worth just over $1 million. Cash remained productive, but did not play as well with the Expos as he had in Philadelphia, eventually losing his job to the defensively superior Rodney Scott.

After the 1979 season, the Expos traded Cash to the San Diego Padres, where he re-assumed his second base job but hit only .227 in 130 games. The following spring, the Padres released the aging Cash, ending his career just before the start of the 1980 season.

At 32, Cash’s playing career was over. For the next eight years, he went on to work outside of baseball, first for an investment firm and then as a car salesman in Pittsburgh. In 1987, while putting in some time as an instructor at a Phillies fantasy camp in Clearwater, Fla., Cash realized how much he missed the game. He contacted the Phillies, who offered him a job as infield coach for their Class-A affiliate in Batavia, N.Y. Given his intelligence and his reputation for leadership, a job in coaching made perfect sense.

Within three years, Cash earned a promotion, becoming the manager of the NY-Penn League team. Cash then worked for several years as the first base coach at Scranton-Wilkes Barre, Philadelphia’s Triple-A affiliate. In 1996, Cash earned a promotion to the Phillies’ major league coaching staff, but later lost his job when Terry Francona was named manager. Cash then returned to coaching with the Orioles’ organization, both at the major league and minor league levels. His last coaching stint came with an independent minor league team in the Golden Baseball League. After the 2010 season, he retired to his home in Florida.

Little did I realize at the time I collected his 1972 Topps card, but I would develop two common bonds with Cash. Fifteen years later after my trip to Gillard’s, during the spring of 1987, I would begin my first job. I was working as a sportscaster for WIBX Radio in Utica - the same upstate town where Cash had spent his formative years in the 1950s and ’60s. There was no way I could have known that I would end up working in that small city in central New York. Heck, I was only seven years old and hadn’t even heard of Utica in 1972.

While working at the radio station, I had a chance to interview Cash over the phone. To my delight, he was not overly serious or annoyed, not the way that his card had portrayed him to be. No, he was as cordial as could be, appreciative of the opportunity to be heard by fans in his hometown of Utica. Not only that, but it was clear that he was intelligent and well-spoken. During our conversation, Cash mentioned his interest in eventually becoming a major league manager. Based on his communication skills and his knowledge of the game, it seemed that Cash was well on his way.

I remained at the radio station until March of 1995, when I started working at the Baseball Hall of Fame. Little did I know that Cash had also become connected to Cooperstown, even if only in a limited way. As a standout amateur playing American Legion baseball, Cash had made several trips to play organized games at Cooperstown’s historic Doubleday Field. It was a ballpark that Cash would return to as a professional, playing for the Pirates in the annual Hall of Fame Game at Doubleday Field. Cash played at Doubleday in the summer of 1973 - the year of Clemente’s posthumous election to the Hall of Fame and just one year after I collected my first baseball card.

Though he had a fine career, Dave Cash will never make the Hall of Fame as a player, and sadly, never did fulfill the dream of becoming a big league manager. Yet, he forged a lasting career for which he should be most proud, playing for the world champion Pirates in 1971, becoming an integral cog to some very good Phillies teams in the mid-1970s, and eventually achieving success as a minor league manager and coach.

On a personal level, Cash will always be an important name. For this collector of baseball cards, Dave Cash will always be the No. 1 card, the one who started it all.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

More Card Corner

#CardCorner: 1991 Topps Roberto Kelly

#Card Corner: 1983 Donruss Cecilio Guante

#CardCorner: 1991 Topps Roberto Kelly

#Card Corner: 1983 Donruss Cecilio Guante

Related Stories

Museum Celebrates ‘Homer at the Bat’ Episode of THE SIMPSONS, May 27 in Cooperstown at Hall of Fame Classic

George Brett returns to get 3,000th hit

#GoingDeep: Cristóbal Torriente Bests the Bambino

Hall of Fame’s BASE Race Takes Runners on Journey through Historic Cooperstown on Saturday

2016 Hall of Fame Classic Features Baseball’s Biggest Stars in Memorial Day Weekend Legends Game

1953 Hall of Fame Game

'Fastball' Headlines Tenth Annual Baseball Film Festival

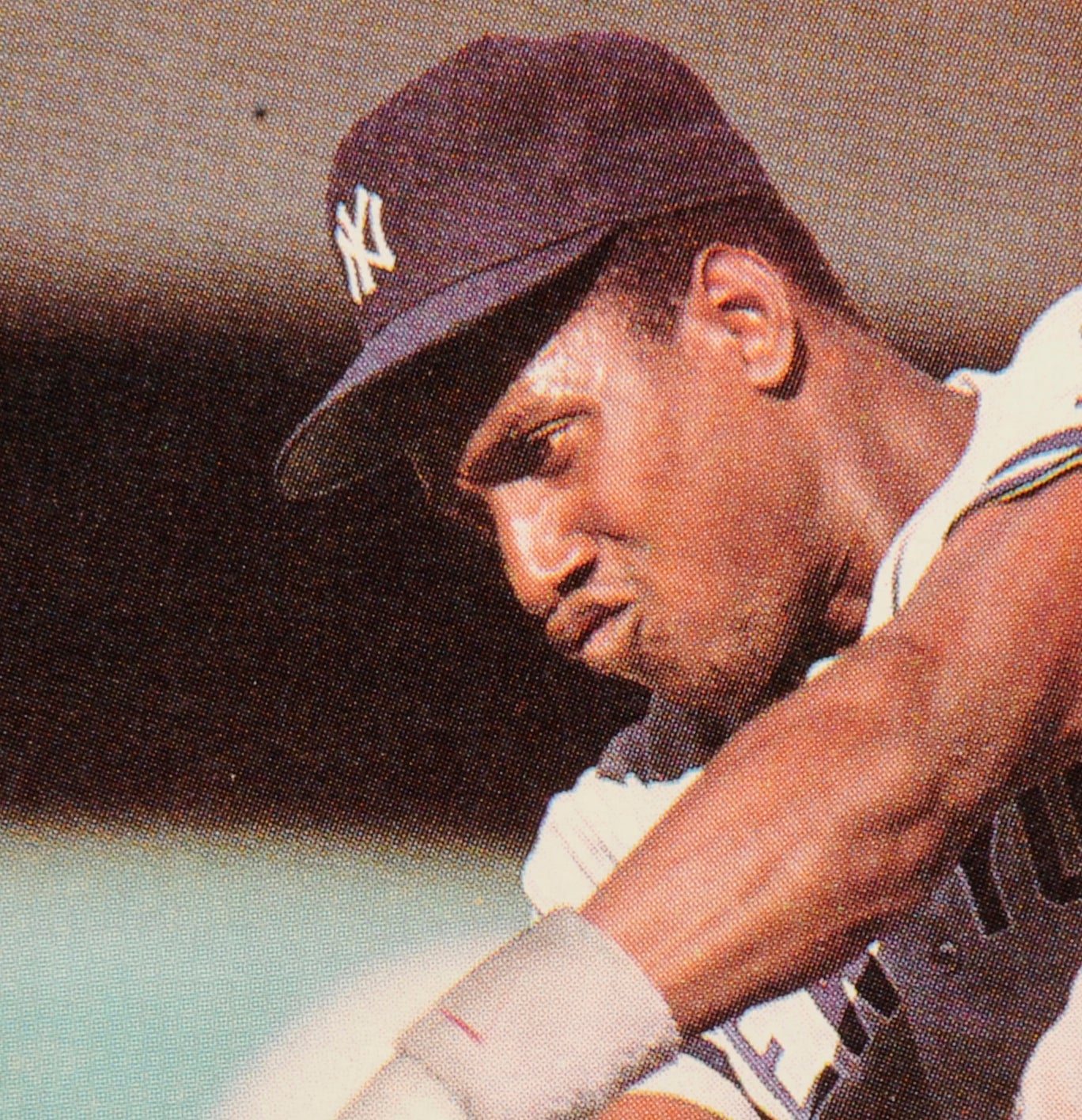

Joe DiMaggio makes his big league debut, recording three hits in the Yankees’ win

01.01.2023

Hall of Fame Weekend 2015 to Feature Inductions of Biggio, Johnson, Martinez and Smoltz, July 24-27 in Cooperstown

01.01.2023

Hall to Honor Curt Flood’s Legacy, World War II Players during Awards Presentation at HOF Weekend

01.01.2023