- Home

- Our Stories

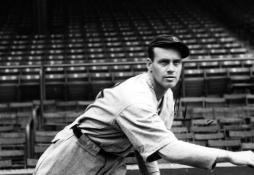

- #CardCorner: 1983 Topps Reggie Smith

#CardCorner: 1983 Topps Reggie Smith

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

I’ve always been fascinated by baseball cards that show more than one player. After all, baseball is a game of action and motion, a team sport that involves interaction, sometimes even collision, between players from two opposing sides. So it’s only natural that many action cards will prominently feature two, or even three players at a time. Sometimes it is the “other” player on the card who grabs more of our attention, either because of his status within the game, or his prominence on the card itself.

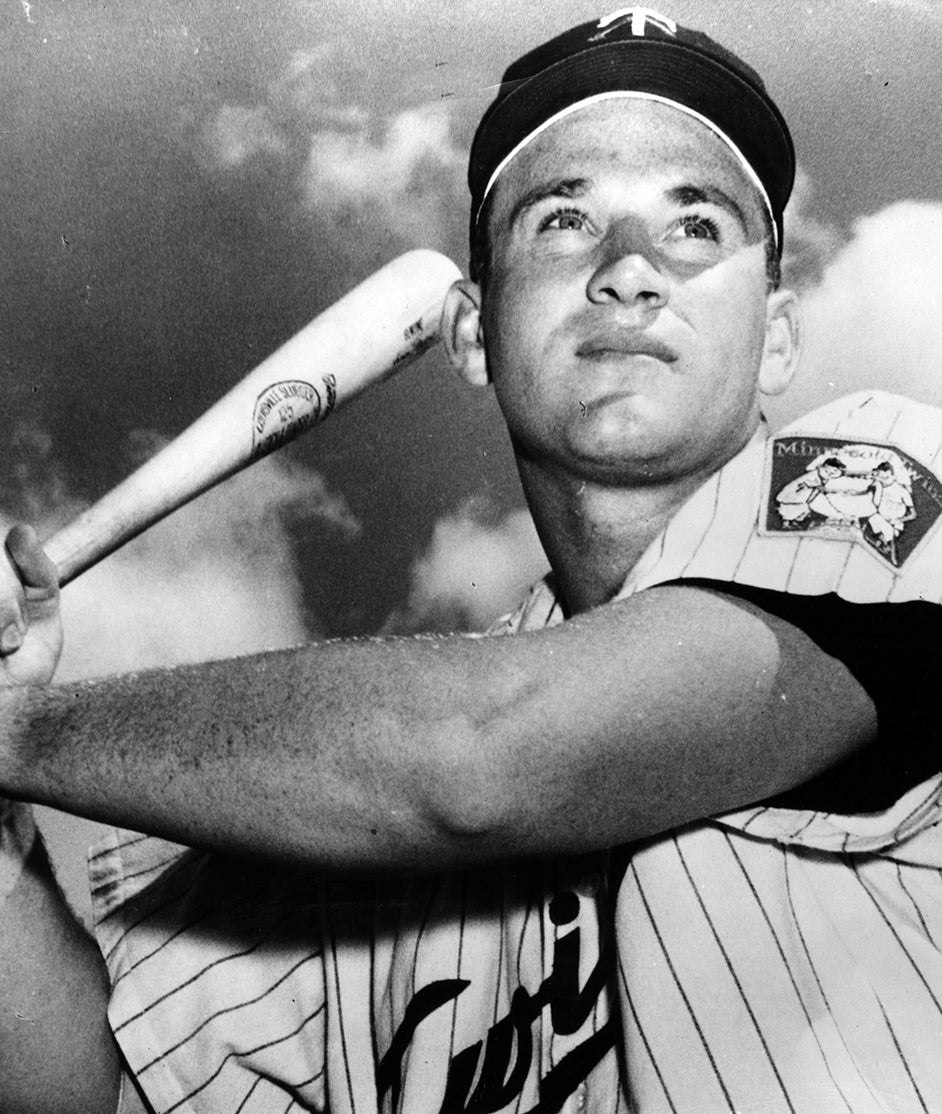

This phenomenon has happened repeatedly on baseball cards over the years. I first noticed it with the 1972 Topps set, which featured a series of “In Action” cards. One of the cards depicted John Ellis, a first baseman with the New York Yankees. As Ellis takes his lead off first base, we see him being held on by Harmon Killebrew, the Hall of Fame first baseman of the Minnesota Twins. The card could just as easily be Killebrew’s card; he takes up as much space on the cardboard as Ellis. Curiously, Killebrew’s presence adds no monetary value to the card. It is still considered a John Ellis card, a common card that can be procured for a couple of dollars if you’re not concerned about acquiring a card in mint condition.

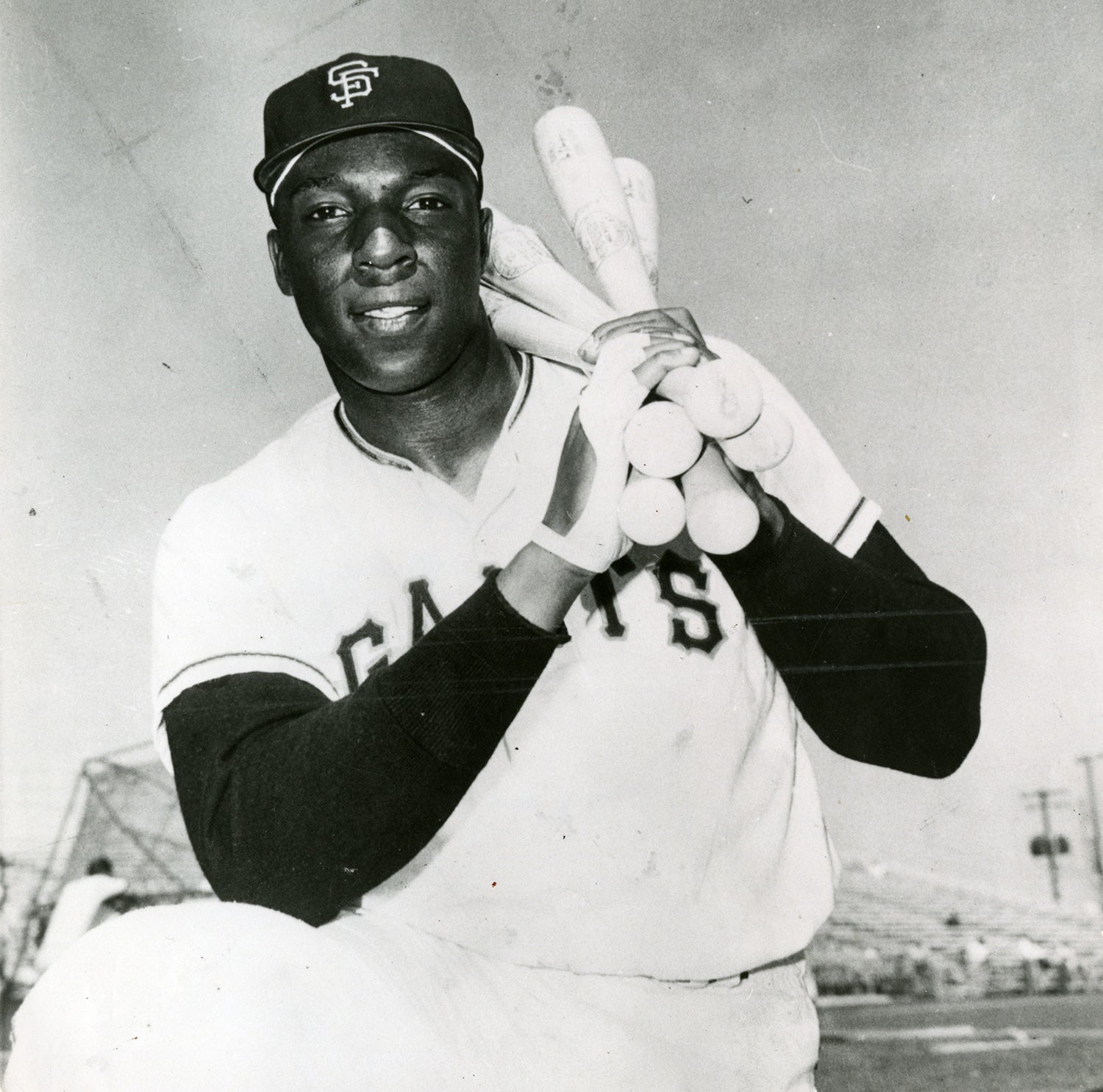

In some cases, cards feature two star players of equal billing. A perfect example can be found in the 1973 Topps set. It is Willie McCovey’s card, an action shot taken during an afternoon game in San Francisco. Batting in a game against the Cincinnati Reds, McCovey has just fouled a pitch into the third base stands. Both McCovey and the catcher look to their left, trying to track the foul ball. The catcher, who is quite evident, is none other than Johnny Bench. So take your pick, a standing McCovey or a crouching Bench. Either way, you can’t lose with these two Hall of Fame icons.

This phenomenon occurred often with the 1973 set, which specialized in long-distance action shots that put several players into the frame. Another example is Steve Garvey’s card. We see Garvey, having just hit a home run, being congratulated by his teammate, Wes Parker, whose last name and number are fully evident on the back of his jersey. But the angle of the photograph makes it impossible to see all of Garvey, whose face is partially blocked off by the back of Parker. (The rest of Garvey’s face is cast in shadow, making his features indistinguishable.) An argument could be made that the card should be Parker’s, and not Garvey’s.

Staying with the 1973 Topps set a moment longer, collectors can find Bert Campaneris on more than just his own player card. Campaneris makes cameos on no fewer than three other player cards: those belonging to Bob Oliver, George Scott, and the wonderfully named pitcher, Rich Hand. It seemed that whenever a Topps photographer like Doug McWilliams popped up at the Oakland Coliseum, he was likely to catch Campy with his camera.

We’ve seen cameos by other players in more recent years, as well. Tony Perez’ 1986 Topps card shows him on the verge of receiving a “high five” from teammate Eric Davis. Mariano Duncan’s 1991 Topps card features him eluding a takeout slide from Hall of Famer Ozzie Smith. And then there’s the terrific 2014 Topps card of Jayson Werth, which shows him in the dugout pointing toward the stands while teammates Ian Desmond and Anthony Rendon look on.

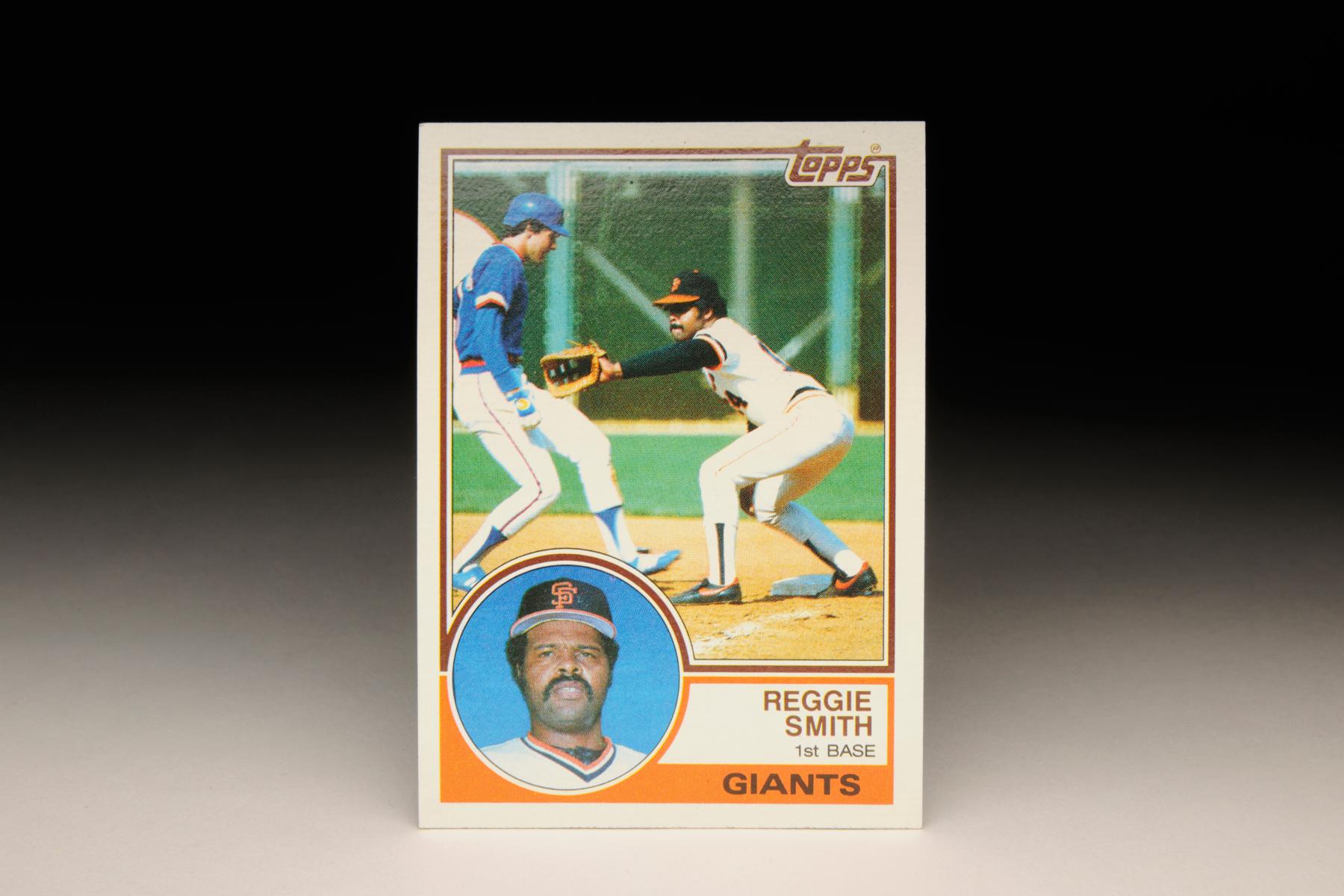

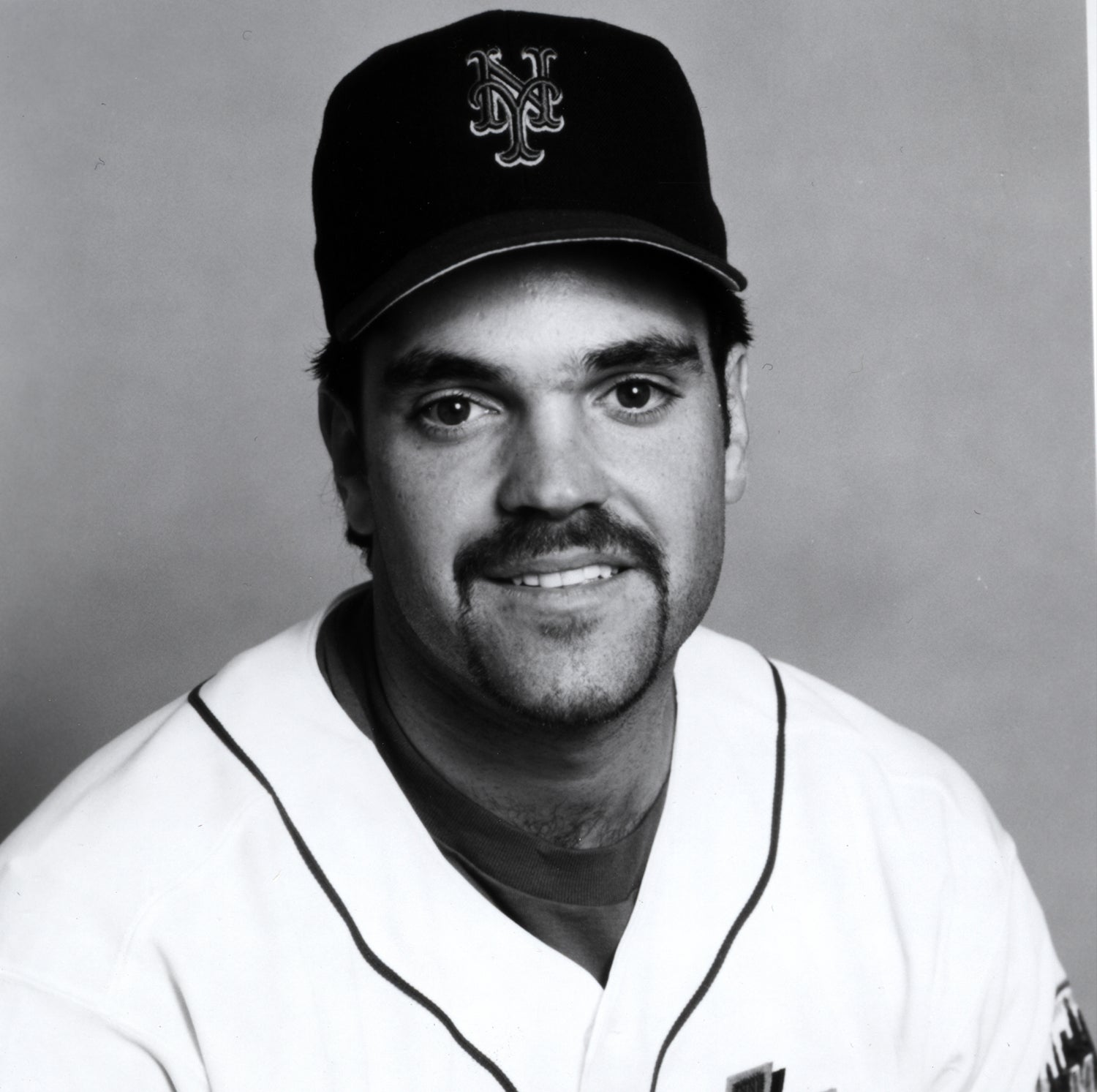

With all that in mind, we come to Reggie Smith’s 1983 Topps card. At the time this card was issued, perhaps only fans of the Chicago Cubs would have immediately identified the other player on the card. Of course, more than three decades later, the identification is easy to make. It is, in fact, a Hall of Famer.

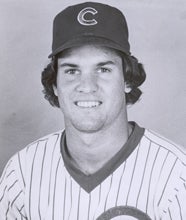

The player in question is Ryne Sandberg; at the time this photograph was taken, sometime during the 1982 season, Sandberg was a rookie third baseman for the Cubs. (He would later move to second base, where he would gain much of his fame for his smooth fielding and silky, soft hands.) We see Sandberg making an unhurried return to first base on a pickoff attempt, with Smith taking the throw. I think it’s safe to say that Sandberg gets back to the base safely and without incident, at least judging by the casual way in which “Ryno” seems to be making his way back to the base.

Sandberg and Smith are not the only familiar features on the card. The other is the iconic background of old Candlestick Park, notable for its chain-link fence running along the outfield. Now demolished, Candlestick Park long had its critics, mostly because of the bone-chilling winds that blew through the stands during night games, but I’ve always thought the park looked good on cards, in photographs, and on television broadcasts. Unlike the cookie cutter stadiums in Cincinnati, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, Candlestick Park retained a distinctive look through much of its history. When the Giants abandoned artificial turf and reinstituted grass in 1979, Candlestick again became a fairly attractive major league park - at least from a distance.

The background provided by Candlestick and the added bonus of a Hall of Famer help make this an intriguing card in a very good Topps set. But let’s not overlook the featured player, who only adds to the appeal and charm of the card. Reggie Smith was one of the most underrated players of his era, a period that stretched from the mid-1960s to the early 1980s.

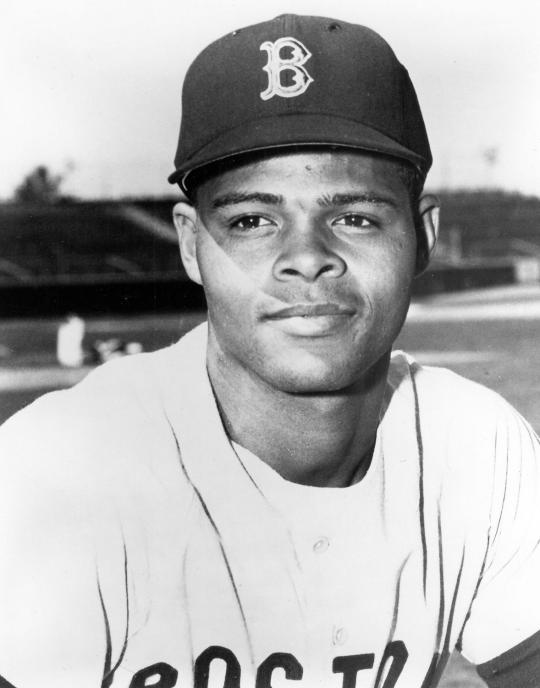

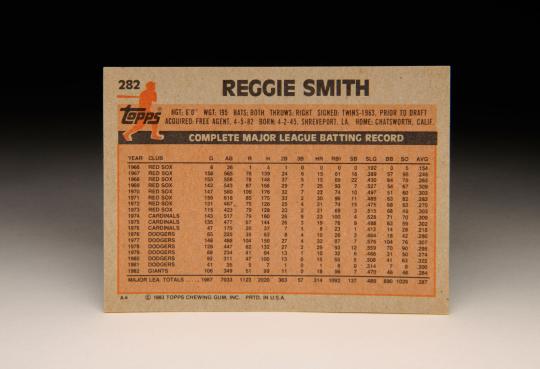

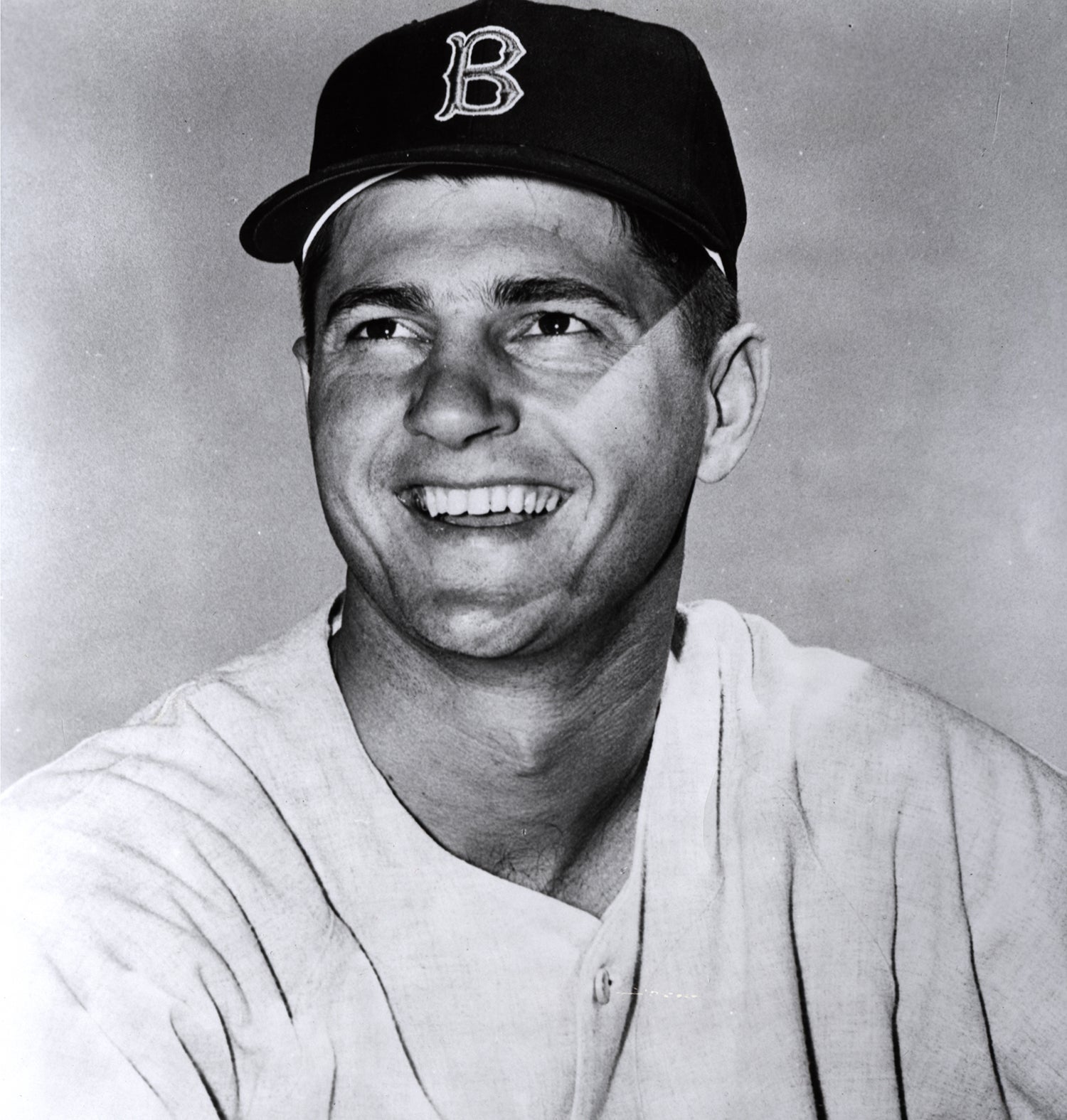

The son of a man who once played in the Negro American League, Smith came to the national forefront in the 1960s. Originally signed by the Minnesota Twins, Smith was left unprotected in the first-year player draft. The Boston Red Sox pounced at the chance, at first assigning Smith to the minor leagues for two additional seasons of seasoning. Smith received his first call-up to Boston in 1966, but didn’t get a permanent look until 1967. After starting the season at second base, he moved to the outfield, emerging as Boston’s starting center fielder. The switch-hitting Smith hit 15 home runs and stole 16 bases, finishing second to Rod Carew in the American League’s Rookie of the Year balloting. He raised his game further in the World Series, hitting two home runs and slugging .542 in a tough, seven-game loss to the St. Louis Cardinals.

Smith became a star for much of the next six years in Beantown. His long list of Red Sox accomplishments included a Gold Glove in 1969 and a power-packed season in 1971, when he hit 30 home runs and led the league in both doubles and total bases.

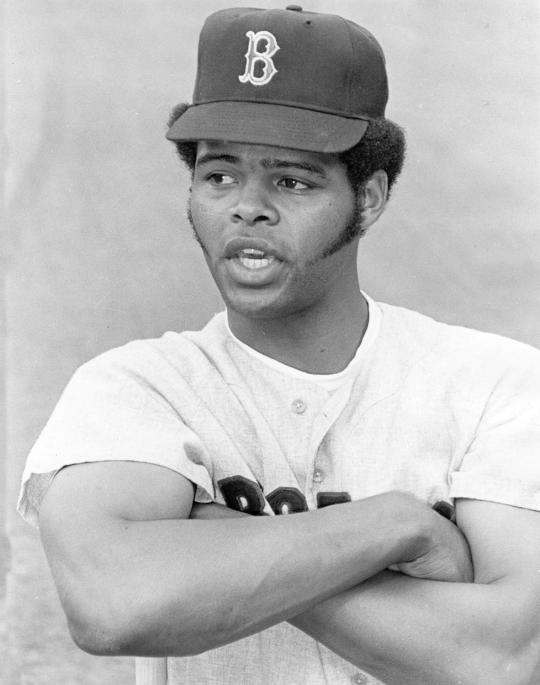

Smith’s performance became more impressive in light of the racial pressures faced by an African American playing in the Boston spotlight. Some Red Sox fans sent him racist hate mail; others decided to express their dislike in person, throwing batteries from the right field bleachers. Another incident took place at his house, where some unknown assailants took garbage cans and emptied their contents onto Smith’s front lawn.

The racial tensions of Boston made life difficult for Smith. “Boston was clearly different from any place I’ve ever played,” Smith told writer Howard Bryant, author of the book, Shut Out. “It was the most divided city that I ever played in… In Boston, you had to know the ground rules. There were places you could go, and places you couldn’t go. It angered me, but it was the way it is.”

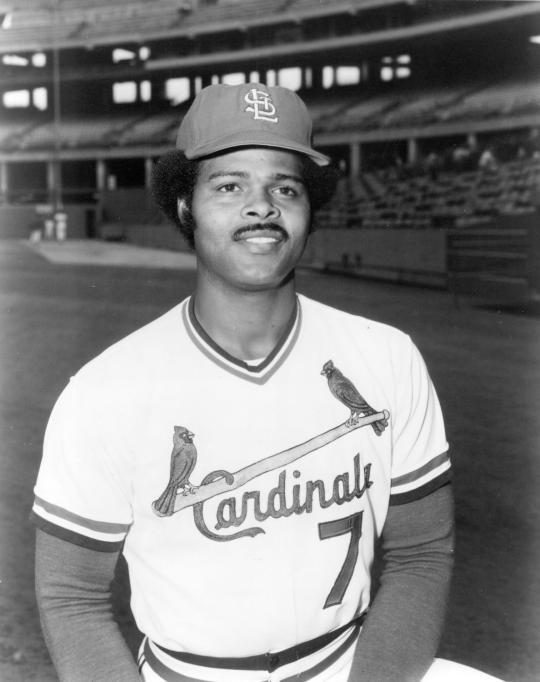

In 1973, Smith put up his best OPS as a Red Sox - .913 - but he also missed more than 40 games due to injury. Frustrated by Smith’s injuries, and perhaps influenced by the treatment of Smith by the Boston faithful, the Red Sox decided to part ways with Smith. That winter, the Sox traded him to the Cardinals for Bernie Carbo, another talented outfielder but not nearly the all-around player that Smith was. The trade was bittersweet for Smith, who had found Boston difficult but had also become close friends with Carl Yastrzemski, the Red Sox’ best known player.

All in all, the trade yielded a good result for Smith, who found St. Louis more accepting of star black athletes. Switching from center field to right field, the intensely competitive Smith enjoyed playing in the National League, with its more aggressive style of play. Smith put in two-and-a-half highly productive seasons for St. Louis, but a glut of outfield talent convinced the Cardinals to make an ill-fated trade in June of 1976; they sent Smith to the Dodgers for a trio of players: veteran catcher/outfielder Joe Ferguson and two minor leaguers named Bobby Detherage and Freddie Tisdale.

The trade represented the steal of the decade for Dodgers general manager Al Campanis. Even though he now had to play half of his games in a hitter’s boneyard like Dodger Stadium, Smith forged the two best seasons of his major league career. At the age of 32, Smith put up numbers that showed an incline, and not a falloff, in his performance. Defying his age, he reached career highs with 32 home runs and 104 walks (104) in 1977, led the National League with a .427 on-base percentage, and achieved a career-best OPS of 1.003. With Smith leading the offense, the Dodgers claimed the National League pennant.

Smith’s performance dipped in 1978, but only by a small margin. His OPS of .942 represented the second best of his career, and his 29 home runs and 12 stolen bases helped the Dodgers win their second consecutive pennant, putting Smith in his third World Series. All along, he continued to play deftly in right field, where he owned one of the game’s most powerful outfield arms.

Over the next three seasons, Smith’s body finally began to show signs of age. Wracked by a serious of injuries to his wrist and shoulder, Smith managed to play in only 201 games over that span. Now 36 years old, Smith left the world champion Dodgers as a free agent, signing a one-year contract with the rival San Francisco Giants. It turned out to be a wise move for San Francisco, which moved Smith to first base, where he shared time with the underrated Darrell Evans and the late Dave Bergman. Though no longer a star, Smith enjoyed a solid season. He hit 18 home runs, compiled a .360 on-base percentage, and slugged a respectable .470.

The Giants understandably wanted to bring Smith back for another season, but they faced competition from the Yomiuri Giants of the Japanese Leagues, who had nearly signed Smith the previous winter. Yomiuri outbid San Francisco, reeling in Smith with a long-term contract and making his 1983 Topps card somewhat irrelevant.

As it turned out, the money amounted to the only good thing about Smith’s deal with the Japanese Leagues. Smith’s personality did not fit what he considered a regressive Japanese culture. Almost immediately, he clashed with his coaches. When he missed time with a legitimate knee injury, fans ridiculed him with the label of “Million Dollar Benchwarmer.” Smith struck out too much for Japanese tastes, earning the insulting nickname, “Giant Human Fan.” Some fans criticized Smith for being dismissive of Japanese culture. A few fans even taunted him with racial epithets.

The situation first reached a boiling point in August of 1983, when Smith decided to put his jersey on backwards and then ran onto the playing field backwards. Smith’s show of protest enraged his coaches, who were not used to such acts of rebellion from their players. The Giants ordered him to leave the field. Later that month, the Hiroshima Carp threw repeatedly at Smith, pitching him up and in. When the umpires did nothing to stop the targeting of Smith, he eventually took matters into his own hands, rebuking the players and coaches on the Hiroshima bench.

In spite of all the culturally fueled opposition, Smith put up terrific numbers for Yomiuri, hitting 28 home runs in 263 at-bats and pushing the Giants to the pennant. Smith remained with Yomiuri through the next season, when age and a series of injuries finally caught up with the 39-year-old slugger. The season reached its low point when a gang of fans assaulted Smith and his son in response to Smith punching a Hanshin Tigers fan a day earlier. At the end of his Far East tenure, Smith referred to the Japanese Leagues as “50 years behind the times.”

Smith’s 1983 Topps card turned out to be his last. At the time, he was better known than Sandberg, who went on to Hall of Fame election in 2005. Ironically, Smith has become somewhat forgotten since this card came out, which is unfortunate, given just how much he did for the Red Sox, Cardinals, Dodgers, and Giants during a long career.

For his part, Smith doesn’t seem to mind the lack of publicity. At one time the hitting coach with the Dodgers, where he tutored a young Mike Piazza, Smith has since left the major league scene. He has turned down a number of coaching offers so that he can work in the shadows as a baseball educator, teaching youngsters to play at a variety of camps that he has operated. In 2006, Smith helped launch Major League Baseball’s Urban Youth Academy, created as a way of exposing the game to inner city youth.

For Reggie Smith, being the “other” guy on a baseball card doesn’t seem to bother him all that much.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

More Card Corner

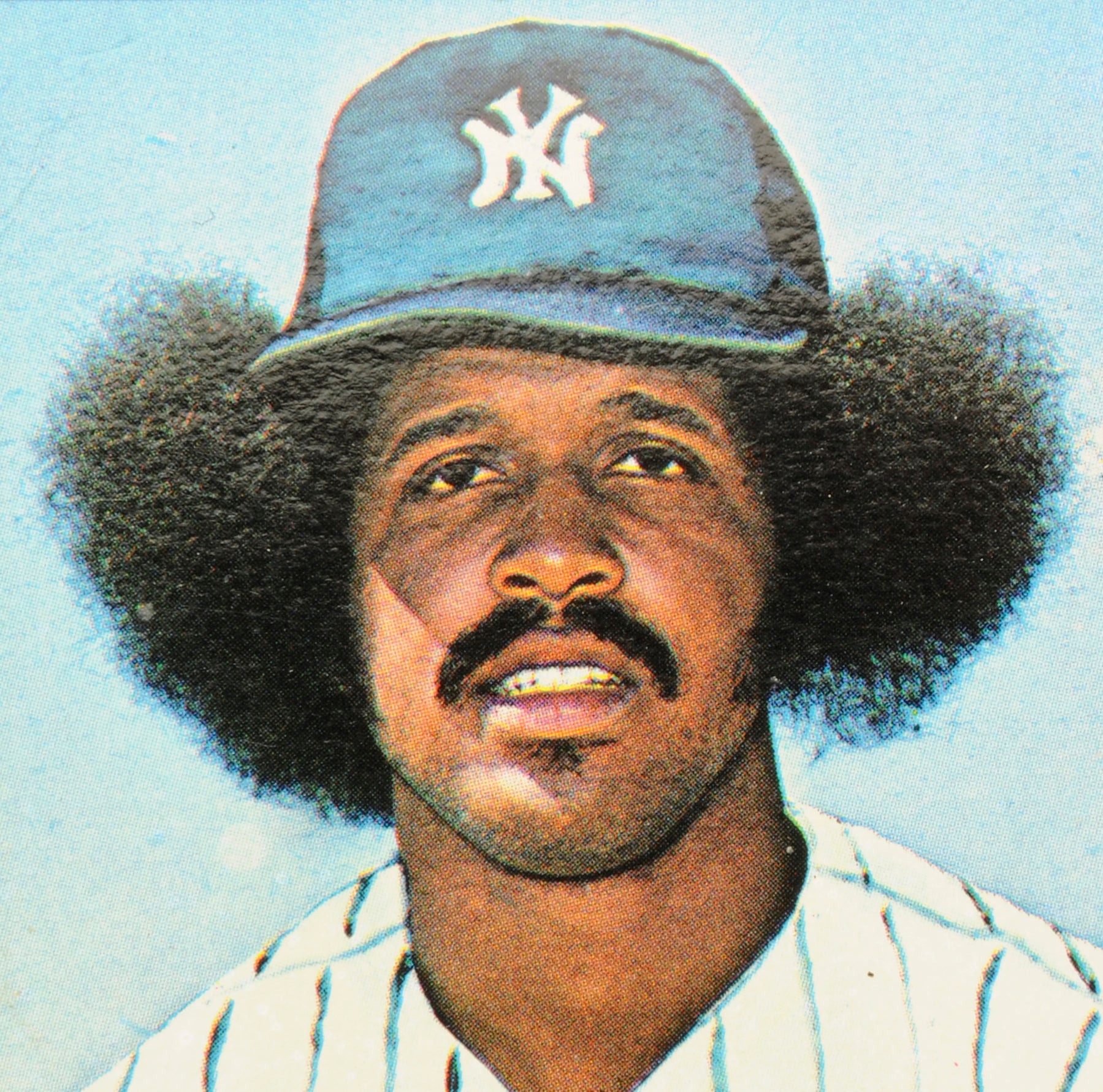

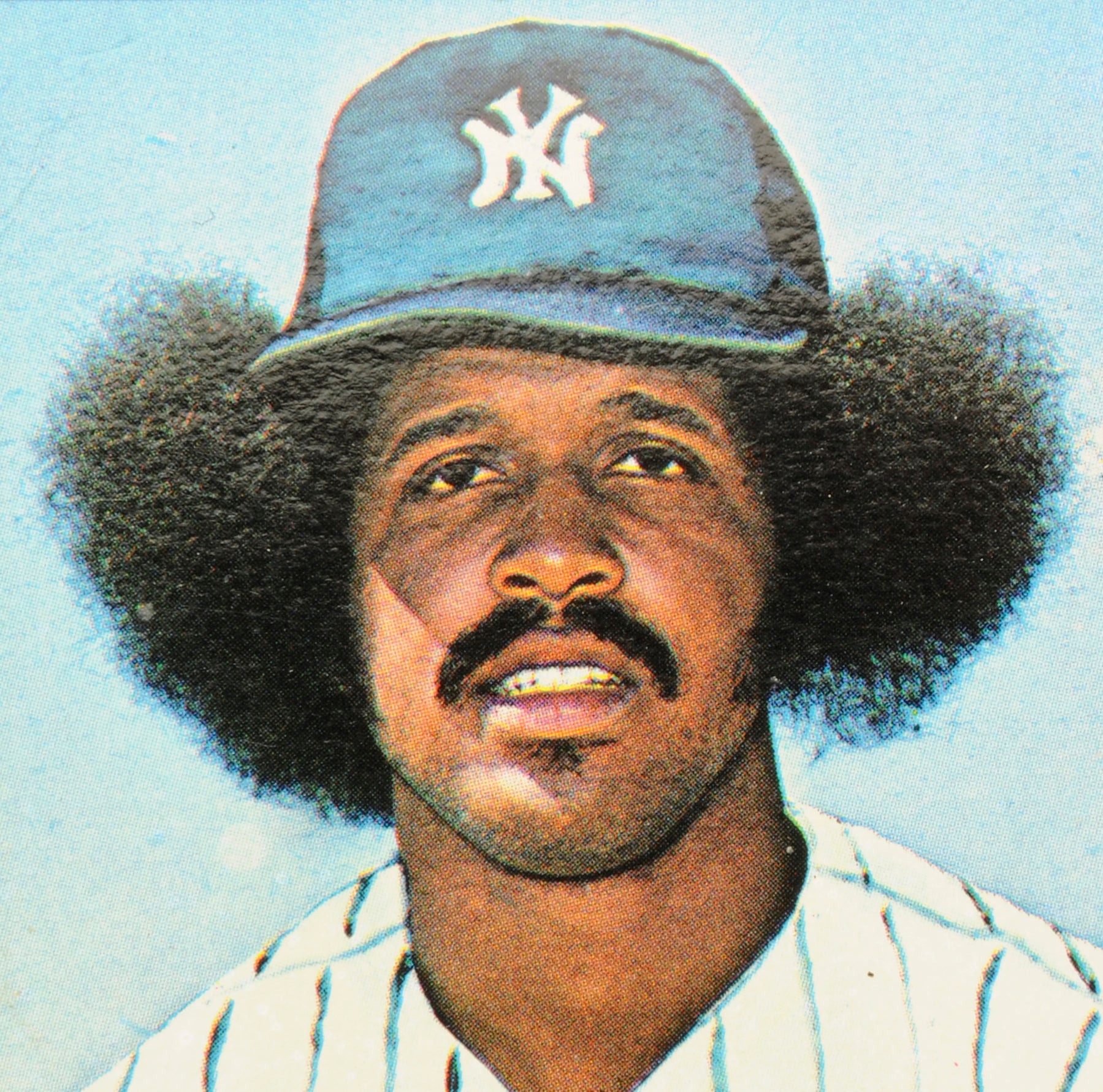

#CardCorner: 1976 Topps Oscar Gamble

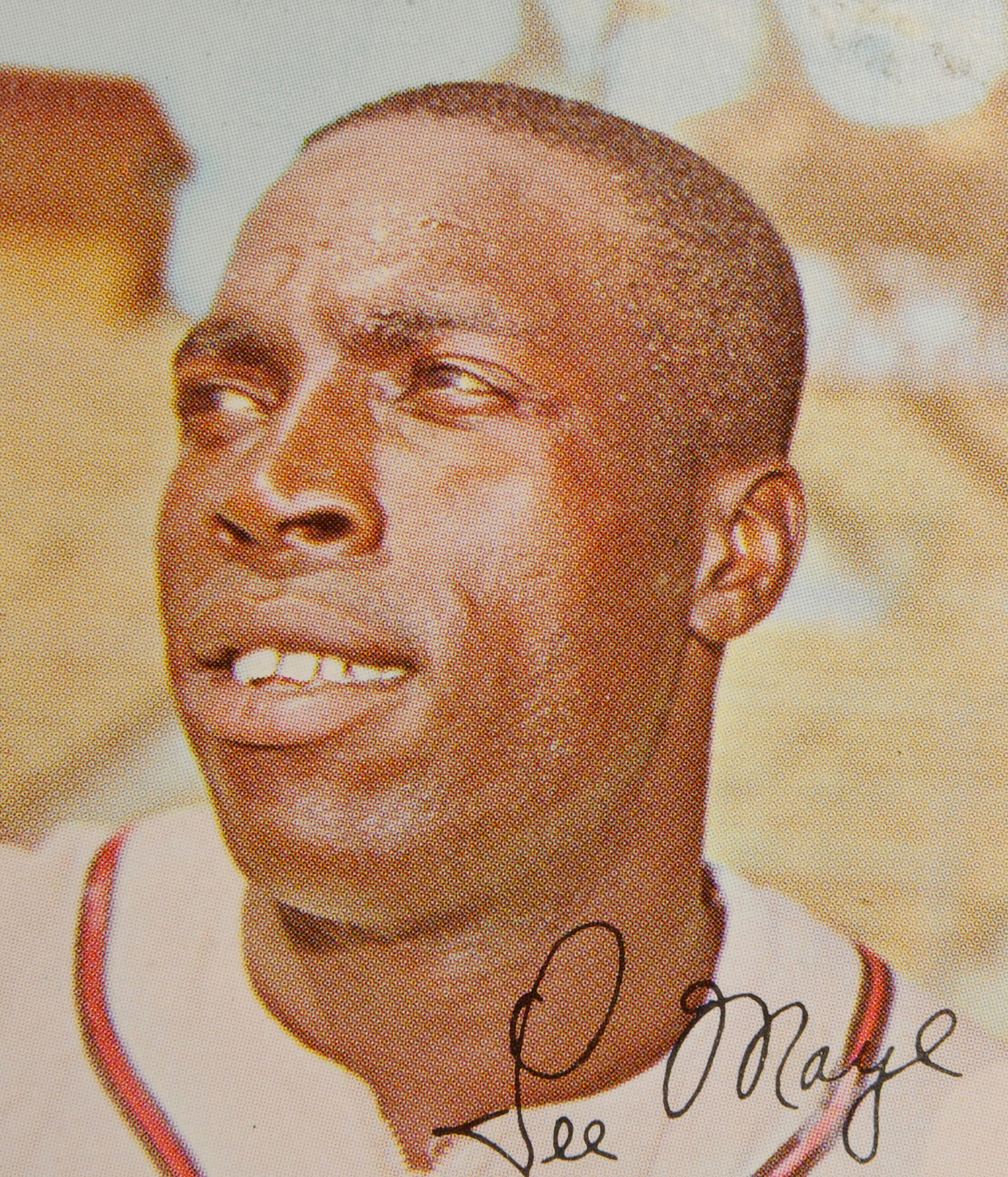

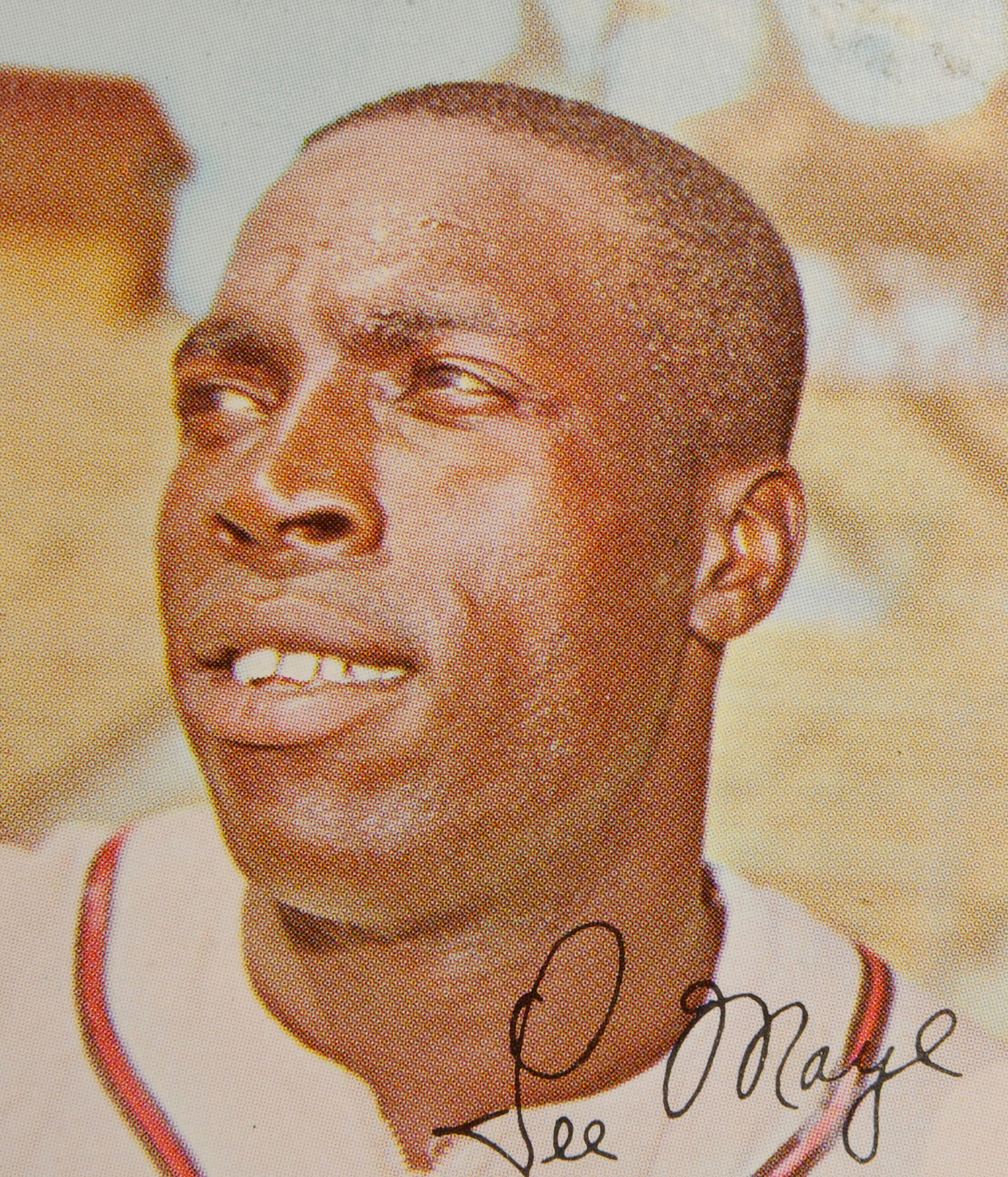

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Lee Maye

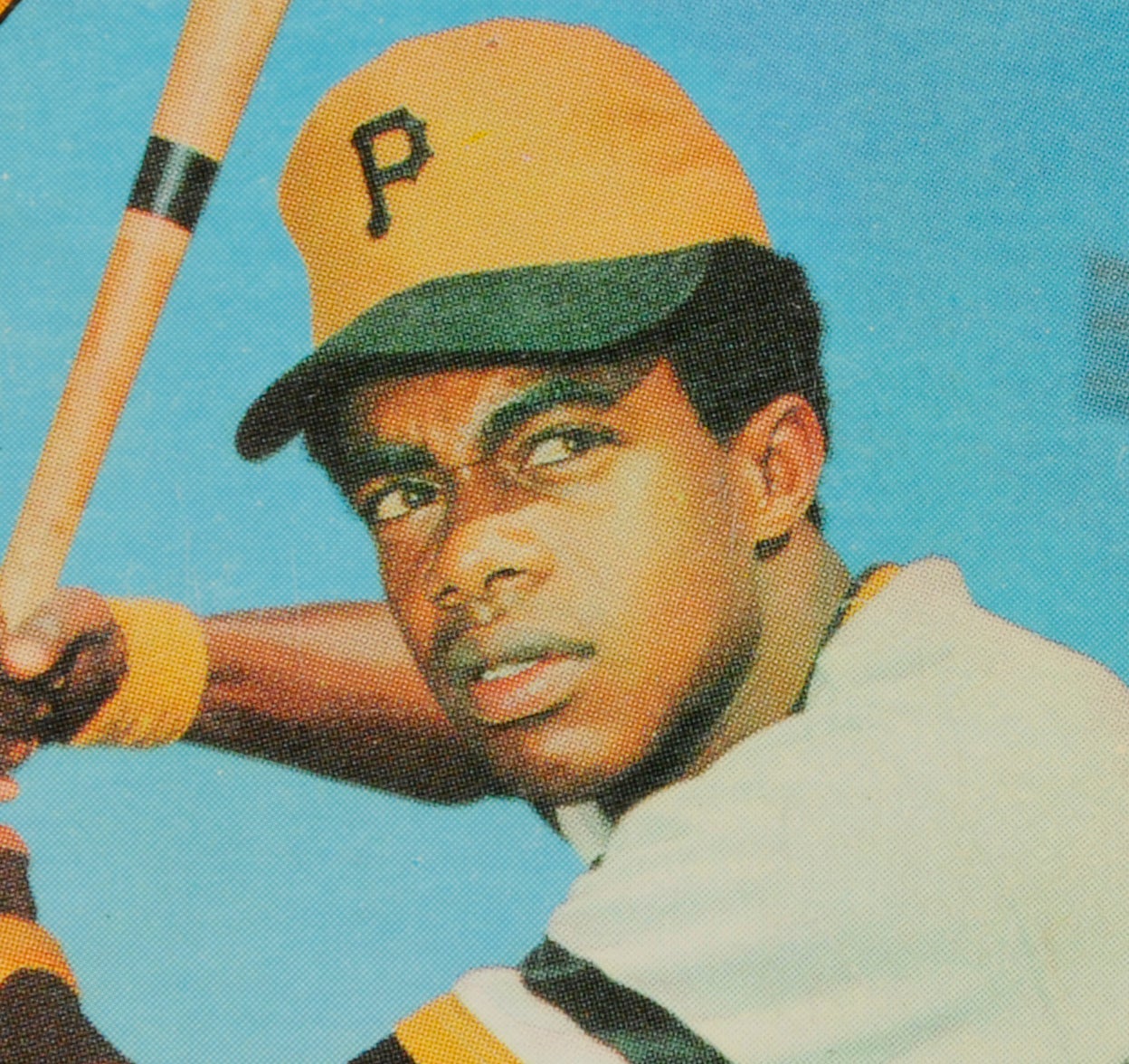

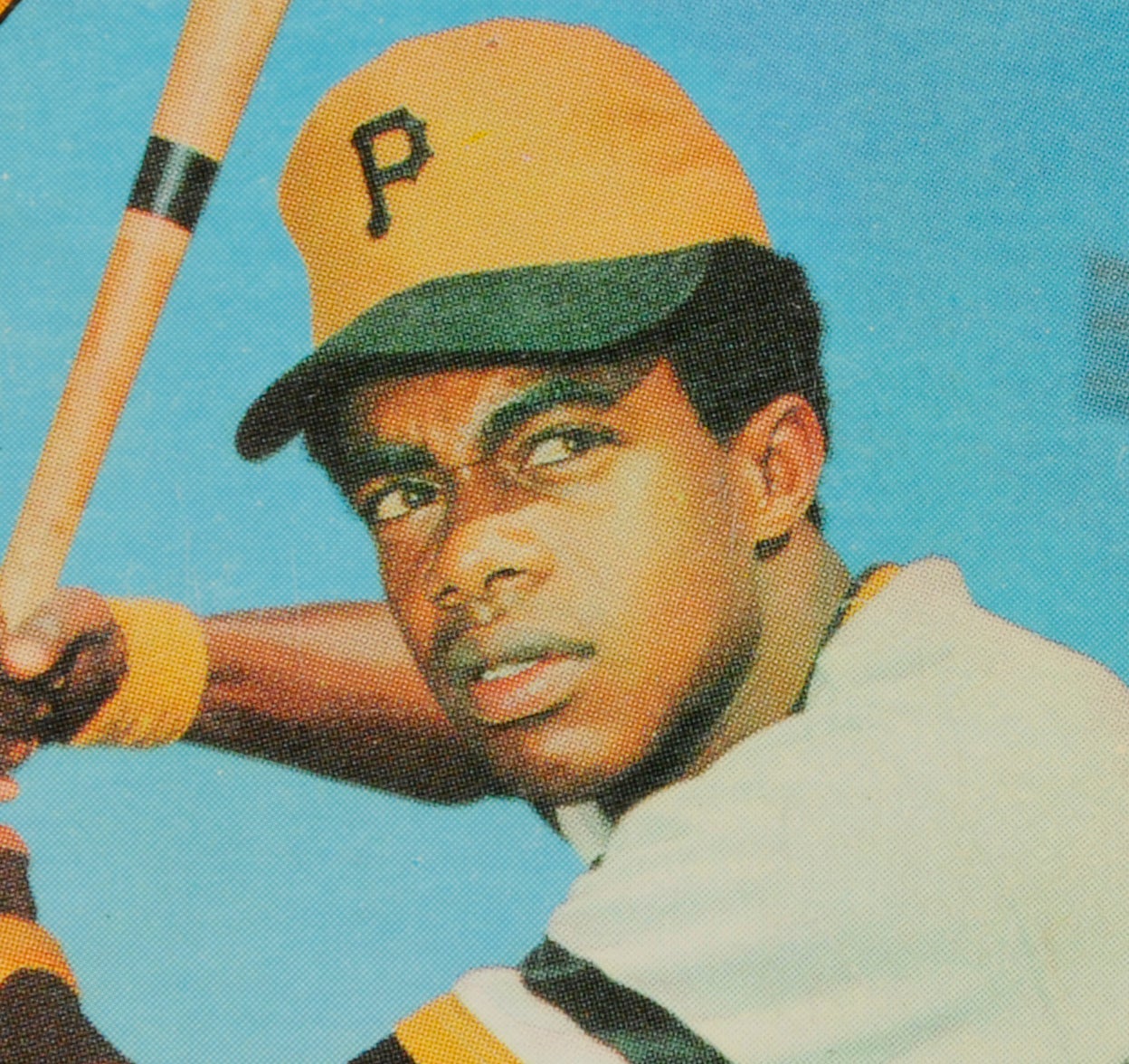

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Dave Cash

#CardCorner: 1976 Topps Oscar Gamble

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Lee Maye

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Dave Cash

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

Caught in the Draft

The National Baseball Hall of Fame Remembers Yogi Berra

Bring Your Little Ghosts and Goblins to Hall of Fame for Halloween Celebration

Hall of Fame’s BASE Race Takes Runners on Journey through Historic Cooperstown on Saturday

Irvin and Thompson debut for Giants

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Elrod Hendricks

Sixteen Ks send Ryan to the record books

1973 Hall of Fame Game

01.01.2023

Baseball Road Show

01.01.2023

Sun, Fun and Baseball: Hall of Fame Classic Thrills Fans at Cooperstown’s Doubleday Field

01.01.2023

BA MSS 67, Folder 15, Corr_1946_4_9b

01.01.2023