- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1991 Topps Roberto Kelly

#CardCorner: 1991 Topps Roberto Kelly

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

When your team finishes dead last, as the New York Yankees did in 1990, and does so mostly with mediocre veterans and few top prospects, it’s difficult to find the silver lining. But not impossible. I suppose there could have been a guy standing on the deck of Titanic shouting, “What a nice view we have of that incredible iceberg!” It’s that kind of blind optimism that many of us find annoying - if not downright aggravating.

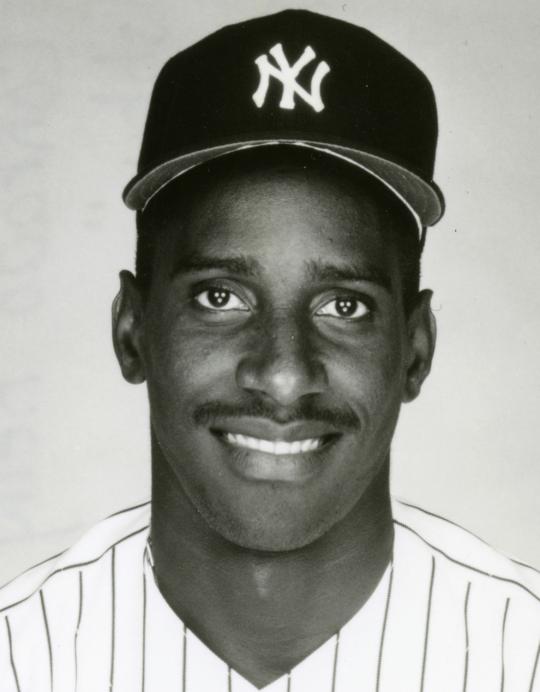

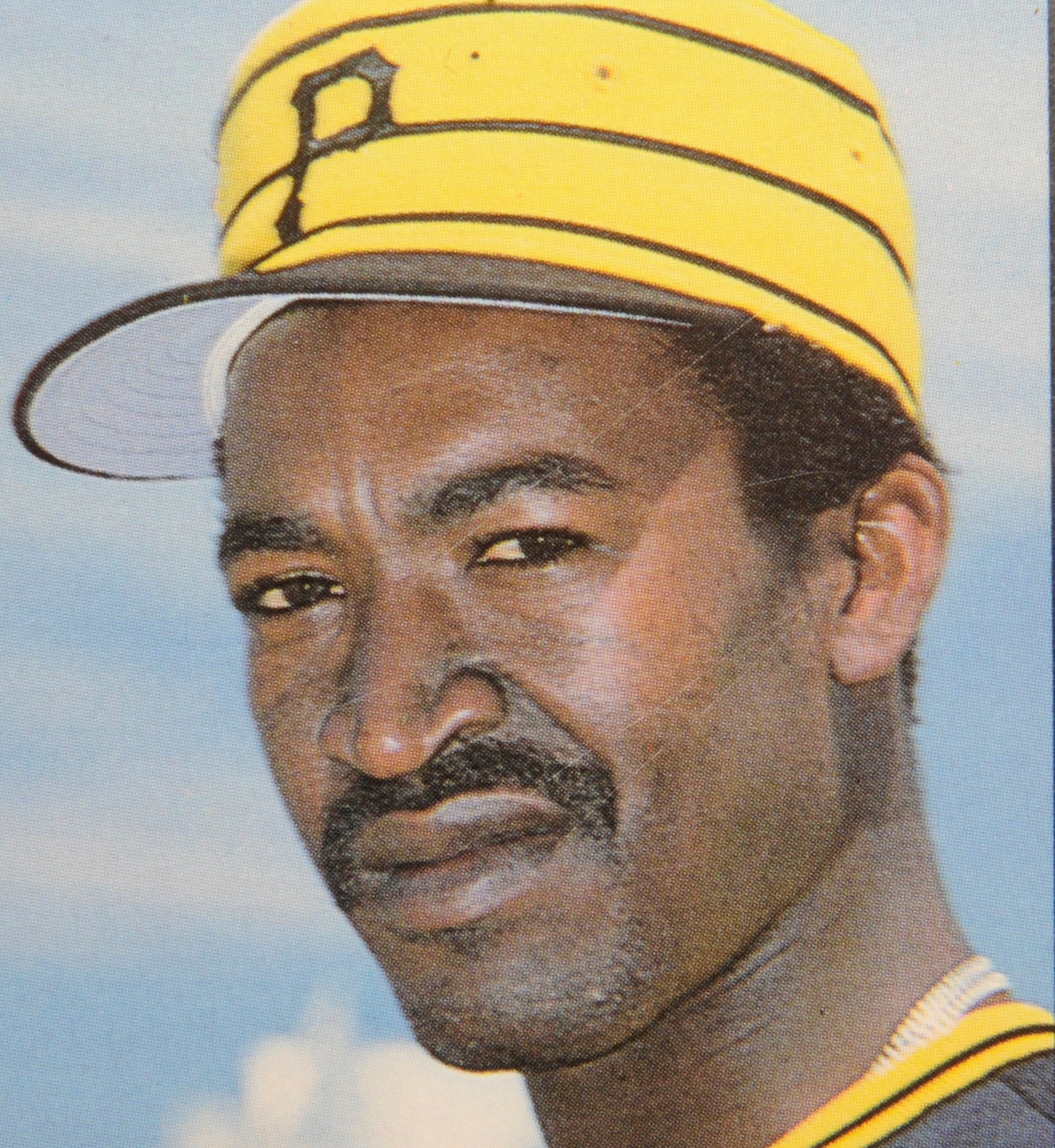

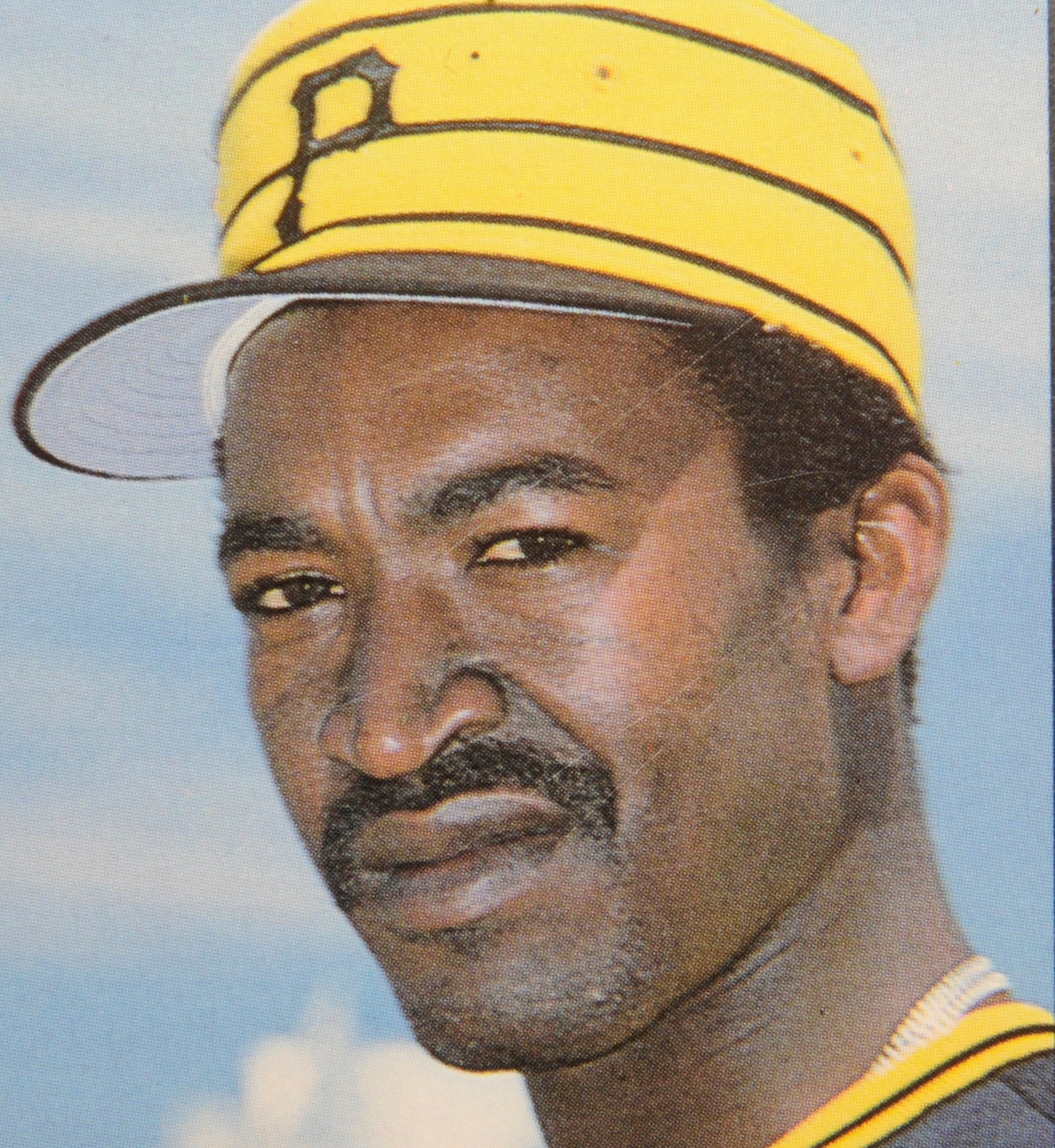

Still, if there was a bright spot to be found on those Yankees teams of the early 1990s, it was Roberto Kelly. The Yankees of 1990-91, who finished last and second-to-last during those two summers, had their share of miscreant characters, including Mel Hall (now in prison for rape and sexual assault) and the late Steve Howe (whose repeated bouts with drug abuse ultimately shortened his career, and probably his life, too). On a team bogged down with too many fringe prospects - good guys but ultimately backup players like Bob Geren and Mike Blowers and Oscar Azocar - Kelly was a legitimate high-level prospect. He possessed four of the requisite five tools, lacking only a strong throwing arm from his post in center field. Kelly also looked like a pure-bred athlete. Long and lean, and well-toned from top to bottom, Kelly looked the part and played the game elegantly.

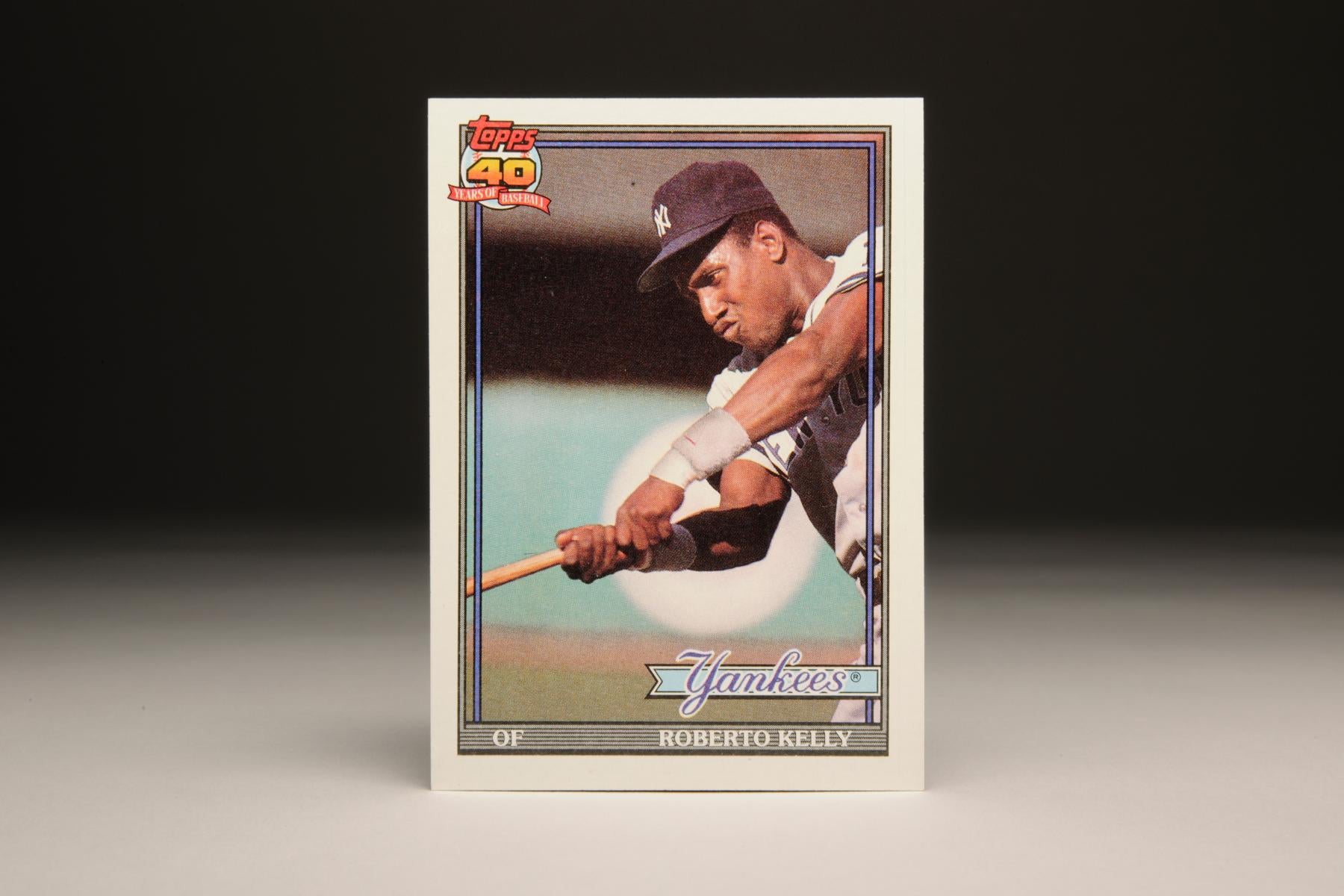

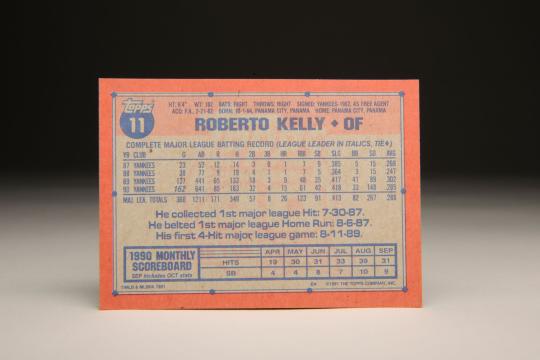

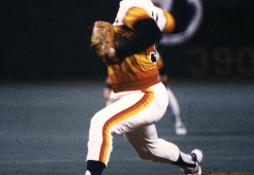

Of all the Roberto Kelly cards that were produced during the 1990s and 2000s, this Topps card - No. 11 in the company’s 1991 set - stands out. To begin with, the 1991 set was arguably the best design of the 1990s. The simple design, featuring a gray outline surrounding a thin blue line, frames the card nicely. The anniversary logo, which celebrates Topps’ 40th annual set, provides the card with a dignified hallmark. In addition, the photography throughout the set is excellent, thanks to well-focused action shots and thoughtful poses like this one.

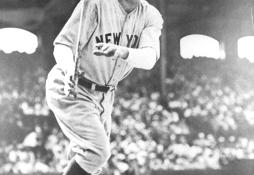

Unlike most posed batting shots, which are photographed from the side or a distant viewpoint, the cameraman has given us the perspective of someone who is pitching to Kelly, but only a inches away as opposed to the standard 60 feet, six inches that separate home plate from the pitcher’s mound. If Kelly were actually swinging at a live baseball here, we could imagine the ball ramming its way through the camera lens. Thankfully, for the sake of safety, there is no ball in play here, only Kelly and the bat. But the Topps photographer still deserves credit for some imagination and ingenuity here. Instead of giving us the routine pose of a batter taking a swing, something we’ve seen thousands of times on baseball cards, the cameraman has turned the shot on its side to give us something creative and vibrant.

Kelly also provides an added touch with his grimace. I’m sure that he is doing nothing more than acting here, because once again there is no ball in play, but the strained facial expression is a pretty good mimic for what we would see during a game. If nothing else, we should give Kelly credit for trying to put on a good show for Topps.

Kelly’s swing didn’t look good solely on his baseball cards. From his first days with the Yankees, the native of Panama had a smooth, picturesque swing. If Kelly could have improved his batting eye even slightly, he could have become a consistent .310 to .315 hitter who could hit 25 home runs, steal 30 bases, and draw 50 to 60 walks a season. It didn’t happen. In some ways, Kelly peaked during his 1989 season, when he batted .302 with 41 walks. After that, his patience at the plate never improved, his batting average regressed substantially, and his strikeout totals mounted. Offensively, Kelly increased only his power, as he reached a high of 20 home runs in 1991.

Even in the outfield, Kelly’s progress seemed to level off. Although he covered a substantial amount of ground with his gliding gait, he sometimes made bad breaks on batted balls and too often looped his throws into no-man’s land. Instead of getting better, Kelly simply stagnated. For a Yankees team desperately in search of building blocks, Roberto Kelly was becoming a source of frustration.

The arrival of Bernie Williams also complicated matters for Kelly. Making his debut in 1992, Williams quickly moved past Kelly in terms of projections for big league stardom. Williams’ ability to switch-hit and his superior power, coupled with better instincts in center field, made him the choice over Kelly. Even the throwing arm of the young Williams, which would become a concern in later years, was better than Kelly’s. So after Kelly muddled through a disappointing 1992 season, in which his home run total fell by half, the Yankees decided to explore trade options and make room for Williams in center field.

Most notably, the Cincinnati Reds made an intriguing offer for Kelly. They agreed to a deal that would send the Yankees veteran outfielder Paul O’Neill and minor league first baseman Joe De Berry. In Cincinnati, O’Neill had become a point of consternation for manager Lou Piniella. His hot-and-cold offensive game, particularly his struggles against left-handed pitching, convinced the Reds that he would never become a star, much less a consistent everyday player.

Gene Michael, the Yankees’ general manager at the time and the subject of an earlier Card Corner, agreed to make the deal on Election Day in 1992. At the time, the trade posed some real questions. Would it be smart for the Yankees to trade the 28-year-old Kelly for the older O’Neill, who had already turned 30? Would O’Neill ever find a way to handle left-handed pitching? A number of Yankee fans, including me, had mixed feelings about the trade. The idea of O’Neill’s left-handed bat at Yankee Stadium intrigued me, but so did Kelly’s all-round potential. If Kelly were to blossom in Cincinnati, the Yankees would forever rue the Election Day deal.

As we all know, O’Neill would elevate his game with the Yankees, while Kelly did not flourish with the Reds. In fact, his career continued to backtrack. Kelly mysteriously devolved from future star to perennial journeyman, bouncing from the Reds to the Atlanta Braves to the Montreal Expos to the Los Angeles Dodgers to the Minnesota Twins over the next five seasons. For one year, he even asked reporters and fans to call him Bobby Kelly. That made him the anti-Roberto Clemente; the Hall of Fame outfielder had once bristled at those who attempted to Americanize him by calling him “Bob” or “Bobby.” After one year with his self-imposed name change, Kelly returned to the traditional “Roberto.” Either way, the name changes did little to alter his falling fortunes.

In 1998, Kelly’s career received a boost when he signed with the Texas Rangers. Over the next two seasons, he became an effective role player, hitting .323 and .300 as a part-time center fielder and DH. In 2000, Kelly returned to New York as a free agent, but he lasted only 10 games with the Yankees, came down with a serious injury, and missed out on playing in the World Series against the rival New York Mets. From there, Kelly spent one season in the Colorado Rockies’ farm system before finishing out his career with two good years in the Mexican League.

In some ways, Kelly’s career turned out the opposite of his promising 1991 Topps card. He seemed to have the kind of talent that differentiated him from the rest of the Yankees of that era, but his career ended up only as very good, and without the expected level of stardom. Even today, I still feel a little bit sad about the playing career of Roberto Kelly.

Thankfully, that is not the end of the Kelly story. Since 2007, he has worked for the San Francisco Giants, initially as a first base and hitting coach, and now as the third base coach. A believer in aggressive base running, he has earned three world championship rings as a coach, a nice reward for the titles the Giants won in 2010, 2012 and 2014. Equally fluent in English and Spanish, he has drawn praise for his communications skills and his work ethic. It would not surprise many within the game if Kelly were to receive an offer to manage a big league club sometime within the next five years.

Given all of that, I feel better about seeing Roberto Kelly’s wonderful baseball card.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

More Card Corner

#Card Corner: 1983 Donruss Cecilio Guante

#CardCorner: 1971 Topps Joe Morgan

#Card Corner: 1983 Donruss Cecilio Guante

#CardCorner: 1971 Topps Joe Morgan

Support the Hall of Fame

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

Cardinals trade Steve Carlton to Phillies

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Joe Foy

Hank Aaron makes his big league debut

Card Corner: 1979 Topps Don Stanhouse

1984 Hall of Fame Game

Nolan Ryan becomes baseball’s first million dollar man

Orel Hershiser debuts on Today’s Game Era Hall of Fame ballot

#CardCorner: 1987 Donruss Mike Krukow

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps David Clyde

Hall of Fame Celebrates World Series Weekend, Honoring San Francisco Giants, Aug. 1-2 in Cooperstown

01.01.2023

1964 Hall of Fame Game

01.01.2023