I came to feel that if, I as a Jew, hit a home run, I was hitting one against Hitler.

- Home

- Our Stories

- Artifacts in Hall of Fame collection tell story of faith within the National Pastime

Artifacts in Hall of Fame collection tell story of faith within the National Pastime

Whether it’s Ryan Braun’s nickname “Hebrew Hammer” or the verse Philippians 4:13 inscribed in Mariano Rivera’s glove, religion continues to make its mark on baseball in the modern age.

Some players are private about their spiritual life, others see their fame on the playing field as a platform for inspiring fans of similar faiths. But this phenomenon is nothing new. It dates back to some of the game’s earliest days, as players like Christy Mathewson, Sandy Koufax and Hank Greenberg opted to sacrifice important moments in their baseball careers to fulfill their personal beliefs.

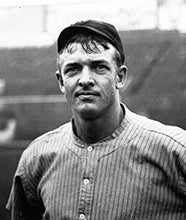

While it’s impossible to wholly understand the depth of personal faith, certain artifacts, now preserved in the Hall of Fame’s collection, can provide insight into what inspired players, and what their impact was on the National Pastime. Mathewson, who was one of the first five players elected to the Hall of Fame, is represented in the Museum’s collection by standard artifacts like balls, bats and gloves. But one artifact is quite unlike the others: A tattered, leather-bound “Sunday School Teacher’s Edition” bible.

The connection between Christy Mathewson’s Sunday school teacher and baseball might not be abundantly clear at first glance. But upon closer examination, the reader starts to detect patterns in what kind of lessons were being taught to Mathewson at a young age. In the subject index, lessons on facing “Adversity” are denoted, while the teacher scribbles notes on future sermons to give:

“God is a kind father. He chooses work for every creature which will be delightful to them, if they do it humbly. He gave us always strength enough, and cause enough, for what he wants us to do. We cannot be pleasing him if we are not happy ourselves.”

It is easy to see how a message like this one could resonate with young Christy, who strictly adhered to the Baptist faith from an early age.

“[John Howard Harris] had been Christy’s boyhood pastor,” Bob Gaines said in his book Christy Mathewson, the Christian Gentleman: How One Man’s Faith and Fastball Forever Changed Baseball. “Harris was energetic, physically fit, a dynamic orator who mixed powerful intellect with a resounding faith. As a child, Christy always sat in the front row, eagerly listening to every word from the pulpit.”

Harris would continue to have a presence in Christy’s life through his college days at Bucknell University, where he regularly attended morning worship. His pastor would preach lessons on “rising as far as your ability will take you” and how “adversity can only make us stronger.” These stuck with him throughout his professional baseball career, as he transitioned to the rough-and-tumble environment of the Giants dugout under John McGraw, a shock to the system for a church-going country boy from Pennsylvania.

“He set a high moral code,” said Philadelphia A’s manager Connie Mack to the Daily Boston Globe. “He was lauded by the churches, ministers used his career as sermon topics, he gave dignity and character to baseball…he was the greatest pitcher who ever lived.”

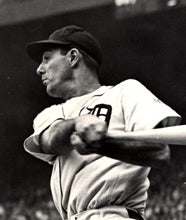

While legions of Christians found their savior in Mathewson, Jewish immigrants found theirs in Hank Greenberg and, decades later, Sandy Koufax. Greenberg was the first Jewish baseball superstar, towering at 6-foot-4 and crushing home runs as if he were hitting ping pong balls. The two-time All-Star almost surpassed the Babe Ruth’s record in 1938, when he hit 58 round-trippers, falling only two short. He would wrap up his career with a batting average of .313, 1,274 RBI, 331 home runs and a .605 slugging percentage.

“At the height of domestic anti-Semitism and the Nazis overrunning Europe, here was a Jewish player so good, so powerful and almost breaking Ruth’s record,” said Aviva Kempner, creator of the documentary “The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg,” to The New York Times. “Two months after Hank nearly broke Ruth’s record, Kristallnacht happened in Germany.”

Greenberg would admit to this sentiment in his autobiography, Hank Greenberg: The Story of My Life. “I came to feel that if, I as a Jew, hit a home run, I was hitting one against Hitler,” he said.

Hammerin’ Hank would publicly display his religious pride again in 1934, opting not to play on Yom Kippur in the midst of a pennant race. Greenberg, would was batting .338 at the time, was carrying the Tigers on his back, so this was not a popular move by most. But it certainly had its’ impact on the Jewish community.

“The only way I would even think that I might have been a hero in those days was the day I walked in Shaarey Zedek Temple and got a standing ovation because I showed up in temple on Yom Kippur," Greenberg said in a 1984 interview with Dick Schaap. "The poor rabbi standing on the podium 'davening,' praying, and suddenly I walk in and everybody in the congregation gets up and applauds. The poor rabbi looks around; he doesn't know what is happening.”

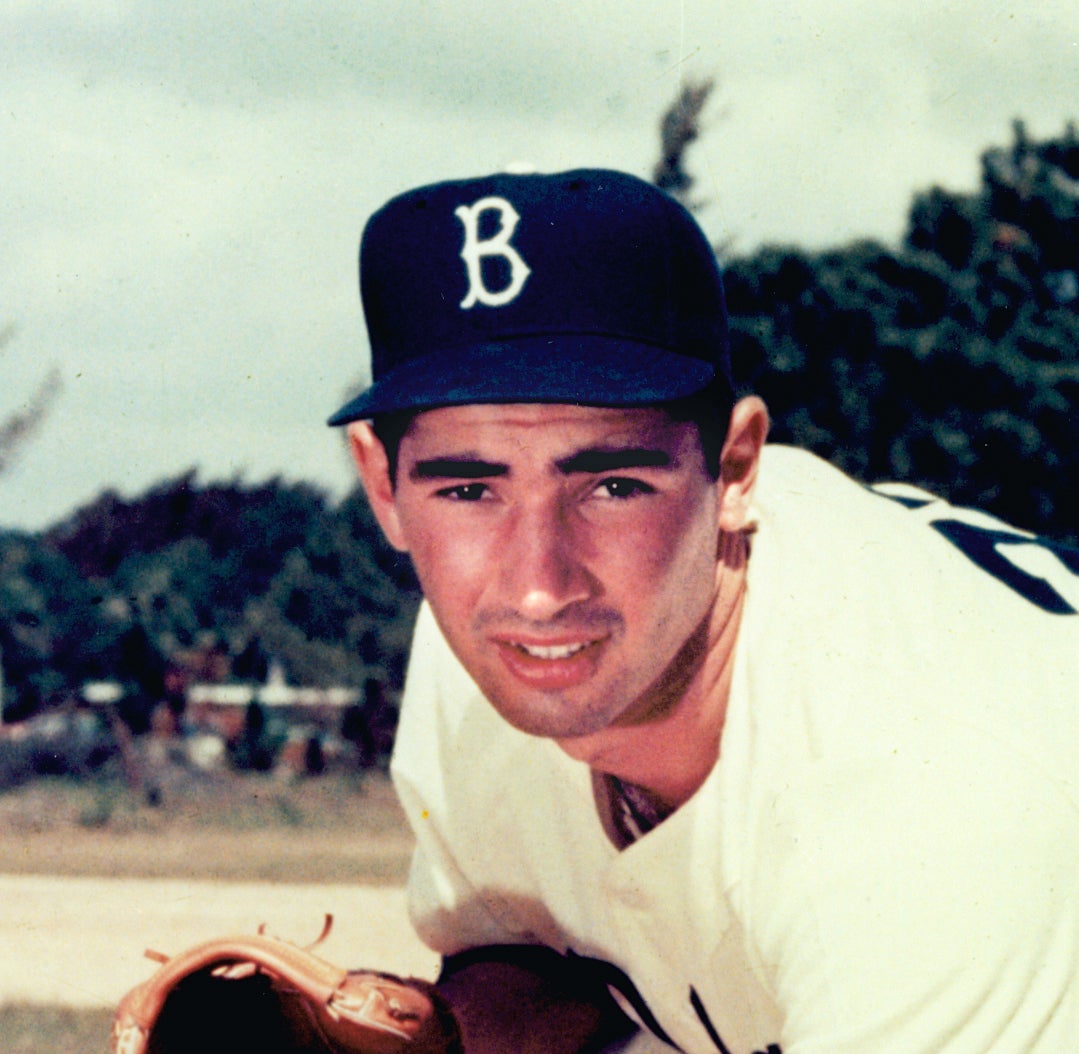

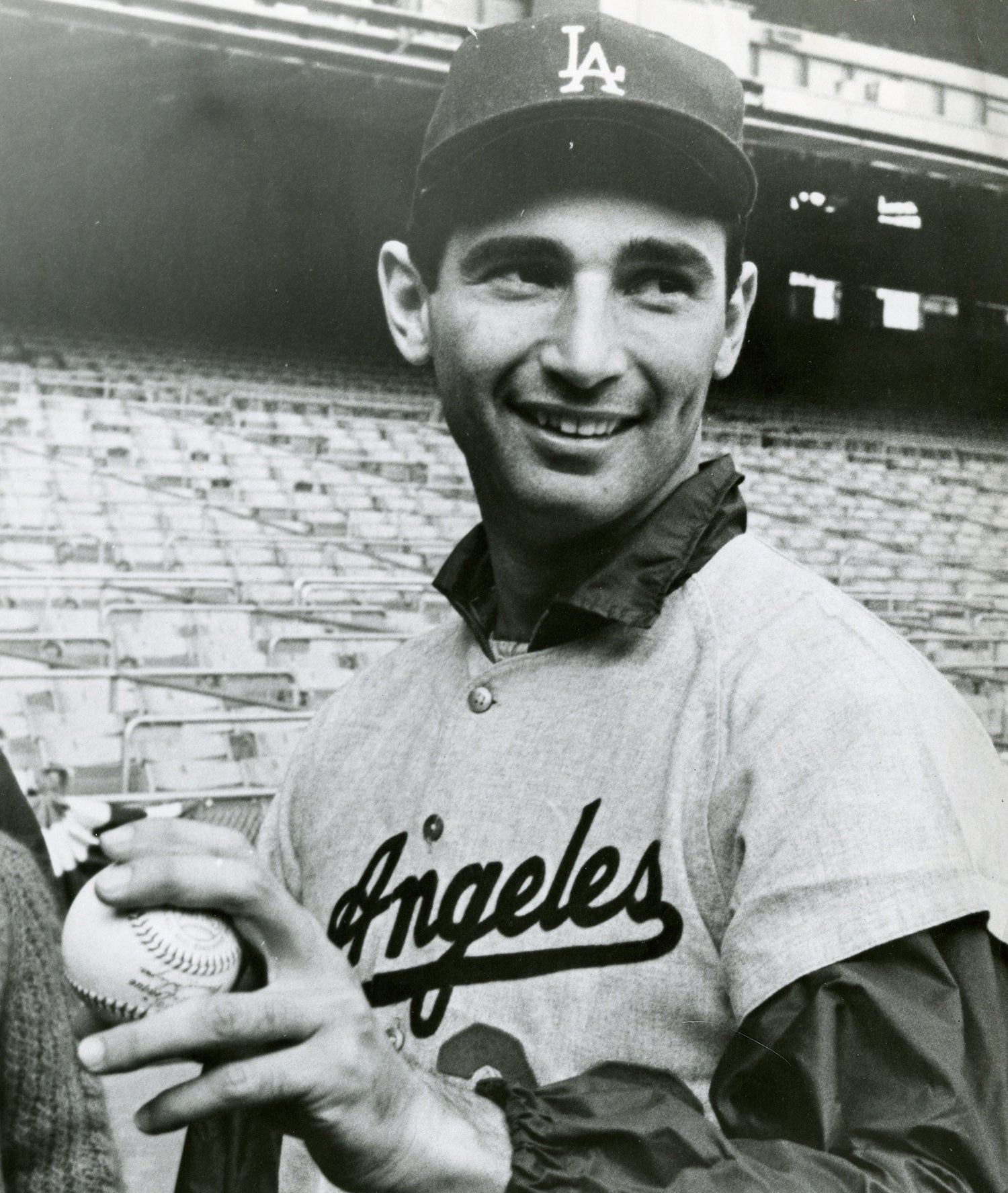

Thirty-one years later, Sandy Koufax emulated Greenberg by declining to start Game 1 of the 1965 World Series because it fell on Yom Kippur.

“There was never any decision to make…because there was never any possibility that I would pitch,” Koufax would say years later, in his autobiography. “Yom Kippur is the holiest day of the Jewish religion. The club knows I don’t work that day.”

For a pitcher nicknamed “The Left Arm of God,” to simply turn down one of the most important games of his career for his religious beliefs, was outrageous to some, but inspiring to others. At that point, Koufax was unhittable, having accumulated two Cy Young Awards, one NL MVP Award and a won-loss percentage of .765 that year. For this, he was elevated from pride of the Jewish community, to icon.

“It’s something that’s engraved on every Jew’s mind,” said Koufax’s Rabbi, Moshe Feller, to Sports Illustrated. “More Jews know Sandy Koufax than Abraham, Isaac and Jacob.”

The impact of players like Greenberg and Koufax still resonates today. It eased the integration process for Jewish immigrants, providing them a source of athletic pride that no baseball fan could deny.

On the second floor of the Hall of Fame in the Whole New Ballgame exhibit lies a navy blue yarmulke, worn by Jewish males, especially those adhering to Orthodox or Conservative tradition. “Yankees” is handwritten on top, in their signature font, with a drawing of their multiple World Series trophies on the other side, beneath the title “CHAMPIONS.” Sandwiched between a pair of knitted Rockies socks and a series of baseball-themed soda bottles, this piece of Jewish tradition dates long before the advent of professional baseball. But over time, as was the case with Mathewson’s effect on Christianity, religion began to embrace the National Pastime as a vehicle for acceptance in American society.

"Baseball is the game that identifies us as Americans to ourselves,” said John Thorn, official historian of Major League Baseball, to National Public Radio. “It was one place in life where it didn't matter who your father was or what your wallet held or what your skin color was. It seemed to me that baseball provided a model for what America might only wish to be or hope to be one day.”

Alex Coffey is the communications specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

The Return of Hank Greenberg

Christy Mathewson: The First Face of Baseball

The Return of Hank Greenberg