“Well, I used to go up to the games with those boys and then I thought it would be fun to write a running story of the game in rhyme."

- Home

- Our Stories

- Poetry man

Poetry man

Baseball is poetry in motion. Appropriate, then, that poetry – and one poem in particular – has captured the essence of the National Pastime for more than 100 years.

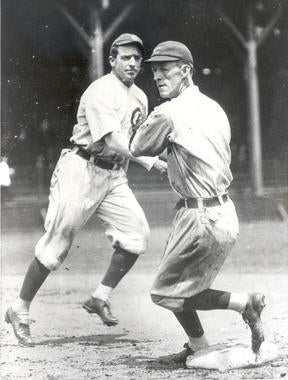

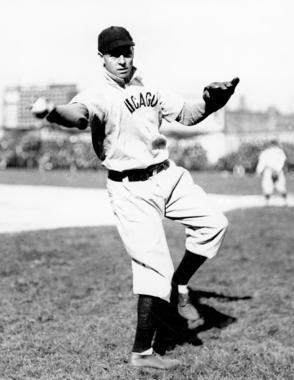

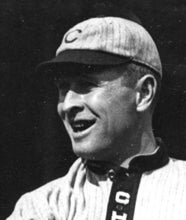

Franklin Pierce Adams used poetry to honor the Chicago Cubs’ early 20th century double play combination of Joe Tinker to Johnny Evers to Frank Chance. His poem initially appeared in the July 12, 1910 edition of The New York Evening Mail newspaper under the title That Double Play Again. It later became better known by a different title – Baseball’s Sad Lexicon.

But Adams’ linguistic accolade to a Hall of Fame infield ballet had more than meets the eye.

And so did its author.

Adams was not, in spite of assumption throughout the decades by baseball enthusiasts, a New York Giants fan that crafted the poem as a lament. He was a Chicago Cubs fan – a transplanted Midwesterner who made New York City his home. Born in 1881, Adams moved to New York City in his early 20s. He stayed there until his death in 1960.

The real source of Adams’ inspiration is just one of thousands of stories preserved by the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

“Beyond keeping a file on every major league baseball player – in addition to files on managers, owners, executives, and famous fans – the Giamatti Research Center maintains files on cultural figures related to baseball, including Franklin P. Adams,” said former Hall of Fame director of research Tim Wiles. “We have a file on Paul Simon because he mentions Joe DiMaggio in the song Mrs. Robinson. We also have one on Ron Shelton, the screenwriter and director that created Bull Durham.”

The Franklin Pierce Adams file overflows with articles about Baseball’s Sad Lexicon, many indicating, mistakenly, Adams’ loyalty to the Giants. J.G. Taylor Spink’s Looping the Loops column in the March 2, 1944 edition of the Sporting News is an exception. It quotes Adams regarding his fandom. “I didn’t like McGraw. I was a Cub fan, for I had come from Chicago, and I got particular delight out of every game the Cubs won from the Giants.”

Adams responded to inaccuracies in the column – including Spink calling Adams’ son Jimmy when his name was Timothy – but he confirmed Spink’s proper recording of fan loyalties.

In an undated letter that Spink published under the title F.P.A. Has His Say, Adams writes, “Mr. H. Grantland Rice, not called Henry by anybody but me, had come to the New York Evening Mail from the Nashville Tenneseean, and as he was a stranger in New York, where I had lived two years, he took an apartment in the building I lived in. Walter Trumbull, then on the New York Evening Sun, also lived in that building.

“Well, I used to go up to the games with those boys and then I thought it would be fun to write a running story of the game in rhyme. I didn’t think much of the stories, and for a good reason – they were no good. But it was fun at the time, and every time the Cubs were in town I took a deep delight in seeing my home town boys beat the cocky New Yorkers.”

Adams’ file also contains a letter dated Nov. 24, 1946 to sportswriter Ernest Lanigan providing background on the genesis of Baseball’s Sad Lexicon.

“I wrote the double play thing for the New York Evening Mail in July, 1910. I was the only Cub rooter in the Polo Grounds press box.

“I wrote that piece because I wanted to get out to the game, and the foreman of the composing room at the Mail said I needed 8 lines to fill. And the next day T.E. Niles [Evening Mail editor] said that no matter what else I ever wrote, I would be known as the guy that wrote those 8 lines. And they weren’t much good, at that.”

Adams’ loyalty to his favorite team contained a hint of schadenfreude – pleasure derived from the misfortune of others, a common trait in baseball fans. In the letter to Lanigan, he writes, “I was always an anti-Giant boy, and I was joyful at the Red Sox and the Athletics victories (in the 1912 and 1913 World Series, respectively), to say nothing of the Cubs of 1906, 1907, 1908, and 1911.”

For the 100th anniversary of Adams’ poem, Wiles joined Jack Bales, Reference and Humanities Librarian at the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg, Va., to research its history. They clarified the poem’s first appearance, original title, and progeny – more than two dozen poems followed Adams’ initial scribble. Adams authored some while his contemporaries authored the others.

Also, Wiles and Bales revealed that Adams did not go to the ballpark after writing the poem – the Cubs were in Chicago then. The Cubs did, however, play the Giants on July 9-11. And on the 11th, the Tinker-Evers-Chance combination turned a double play.

Literary pursuits for Franklin Pierce Adams manifested beyond recording the Cubs’ double play exploits, though. Way beyond.

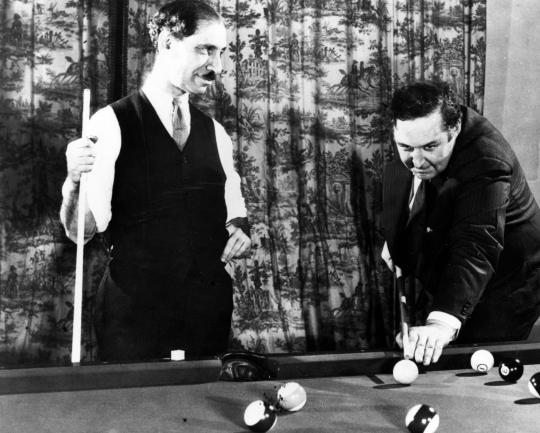

Adams enjoyed membership in the Algonquin Round Table, a group of writers that met regularly at the Algonquin Hotel in Manhattan. These writers helped shape 20th century American culture.

In her 1986 biography F.P.A. – The Life and Times of Franklin Pierce Adams, Sally Ashley states, “F.P.A. and his clever friends showed what the good life consisted of and that, democratically, it lay within the grasp of all. Post-World War I Americans nursed an intellectual inferiority complex, even while they strutted and bragged. Across the country an intense desire for self-improvement swelled, so it was important to know what books to read and what to think about them, what sports successful men followed, what professional teams they rooted for, what topics civilized conversation included.”

Franklin Pierce Adams’ body of work includes columns with the military newspaper Stars and Stripes, Chicago Journal, New York Evening Mail, New York World, New York Tribune, New York Herald Tribune, and New York Post.

But Adams’ sad lexicon remains, at least for baseball fans, his biggest literary achievement.

David Krell is a freelance writer from Jersey City, N.Y.

Baseball's Sad Lexicon

These are the saddest of possible words:

“Tinker to Evers to Chance.”

Trio of bear Cubs and fleeter than birds,

Tinker and Evers and Chance.

Thoughtlessly pricking our gonfalon bubble,

Making a Giant hit into a double--

Words that are heavy with nothing but trouble:

“Tinker to Evers to Chance.”

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Kaat

Griffey Jr., Piazza elected to Hall of Fame

Griffey, Piazza honored by Hall election

Class of 2016 Reflects on Election

Larkin and Santo join baseball’s elite

The Winter of Baseball Life

Nolan Ryan pitches third no-hitter of his career

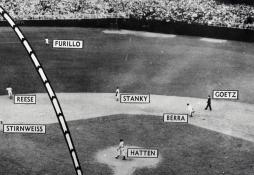

Gionfriddo robs DiMaggio of an extra-base hit in Game 6 of 1947 World Series

Hall of Famer Carlton Fisk Featured in Nov. 7 Voices of the Game event as Museum Unveils Whole New Ballgame Exhibit

Experience History at the Museum During Hall of Fame Weekend 2016, July 22-25

1950 Hall of Fame Game

01.01.2023

BA MSS 67, Folder 15, Corr_1946_4_24

01.01.2023

Relive Inductees’ Hall of Fame Weekend Journey at Legends of the Game Roundtable Event

01.01.2023