- Home

- Our Stories

- Stepping into a legend’s shoes

Stepping into a legend’s shoes

After the 1926 season, two of the American League’s greatest centerfielders, Tris Speaker and Ty Cobb, entered the open market. For Connie Mack, the Philadelphia Athletics’ manager, the prospect of having one of these players to bolster his outfield was rather intriguing.

Philadelphia, led by hurler Lefty Grove, catcher Mickey Cochrane, and outfielder Al Simmons, was challenging the Yankees for supremacy in the American League, and they were on the cusp of overtaking New York.

Spurned by Speaker, who signed with Washington, Mack decided to make Cobb his next target. The Tall Tactician had to contend with the St. Louis Browns’ new manager, Dan Howley, for Cobb’s services, but he eventually made an offer to snare the Georgia Peach.

Cobb, who had just turned 40 earlier in the offseason, announced his decision at a Feb. 8 dinner for the Philadelphia sports writers. He would join Simmons and Walt French in the Athletics’ outfield. Mack, unaware of the history that was about to be made by the 1927 Yankees, liked his team’s chances with Cobb in the lineup.

“Ty Cobb is going to help us a lot,” Mack insisted to reporters. “His presence in the field will inspire the rest. I will say the A’s this year rate with the best, and unless some team starts going above its normal speed, we should be out in front at the end.”

Unfortunately for Mack, even with a 91-63 record, the A’s still finished 19 games behind the unstoppable Yankees in 1927. After a difficult final season in Detroit where he appeared in just 79 games, Cobb enjoyed a brief resurgence in Philadelphia, appearing in 133 games, hitting .357, and driving in 93 runs in 1927. Simmons, Cochrane and Cobb paced the A’s, who also received strong contributions off the bench from future Hall of Famers Eddie Collins, Zack Wheat, and Jimmie Foxx. Grove and Rube Walberg led the team’s pitchers.

Mack and Cobb conferred that November regarding the outfielder’s status. At the end, Mack announced that Philadelphia would release Cobb, who had toyed with the notion of retirement.

“Cobb came to us last season under a very heavy contract,” Mack said. “And we feel that we are unable to continue the high salary next year. I am very sorry that we will lose him.”

Philadelphia then replaced Cobb with the other center fielder they wanted the year before, Speaker. But in spite of his potentially high salary demands, Mack was not about to give up entirely on Cobb.

In late February, as major league teams convened for Spring Training, Mack was hopeful Cobb would make the trip to Florida to rejoin the A’s.

“He has not committed himself but I hope that Cobb will be back for another year with the Athletics,” Mack told the press. “He has promised to let me know one way or another sometime next week.”

Sure enough, on March 1, Cobb agreed to join the Athletics, the only team he would have preferred to play with in 1928, even though he received other offers. Cobb said the “terms were highly satisfactory to me” and accepted Philadelphia’s offer – reportedly less than he received in 1927 – despite his wishes to retire.

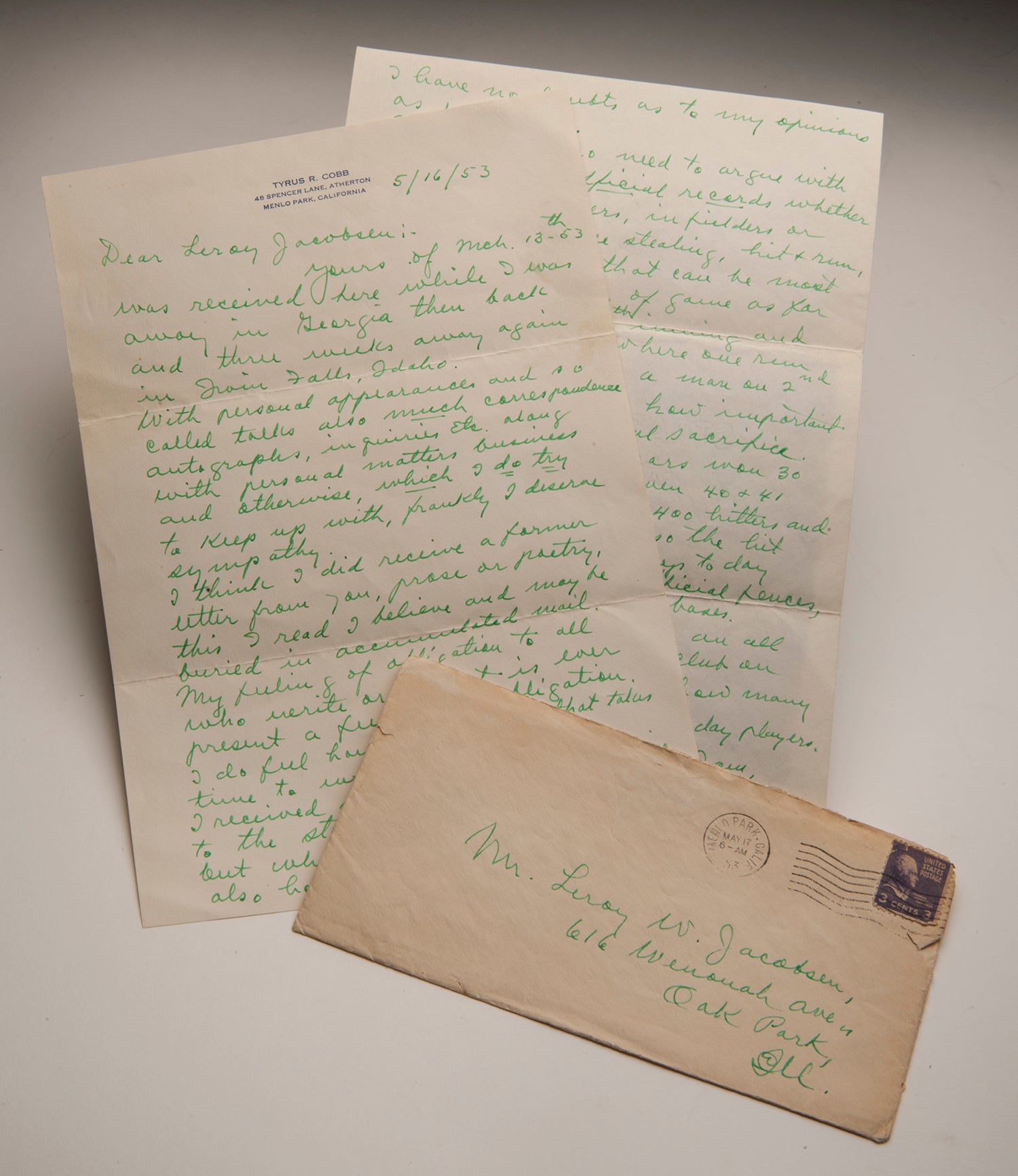

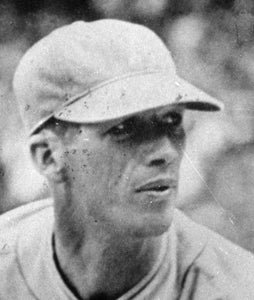

Ty Cobb (left) and Tris Speaker, two of the best centerfielders of their time, were both sought after by Connie Mack to join the Philadelphia Athletics. They ended up playing together during the 1928 season. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Share this image:

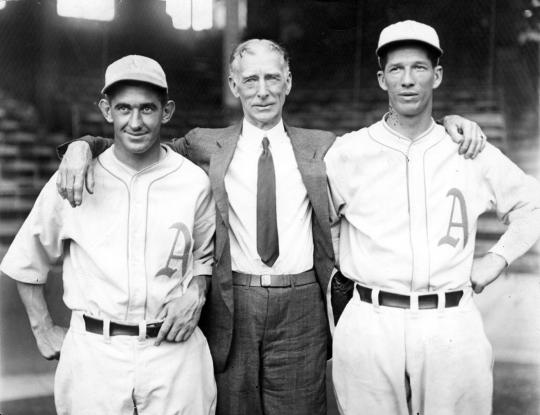

Mickey Cochrane (left) and Lefty Grove (right) helped Connie Mack win his fourth and fifth World Series titles in 1929 and 1930. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

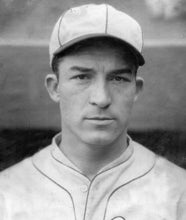

Cobb's 1928 season with the Athletics would be his final season in baseball, at age 41. He hit .323 in 95 games, and started most games in right field. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Share this image:

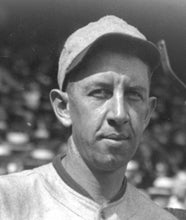

Ty Cobb agreed to rejoin the Athletics on March 1, 1928, despite receiving other offers from teams. He would retire at the end of that season, after 24 years in baseball. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Share this image:

At 41, though, Cobb’s performance was far from the previous year and far from what fans had been accustomed to seeing – wearing these spikes at various points, he hit only .323 in 95 games. Starting in right field much of the season, he transitioned into a pinch-hitting role in very limited action in August and September. Bing Miller, acquired from the Browns before the season, replaced Cobb in right field.

Announcing his intentions to retire in mid-September, Cobb wished the best of luck for Philadelphia because he wanted “to see Connie Mack, the squarest man in baseball, win the flag.”

Playing their last 24 games on the road, the 1928 Athletics came close – finishing 2.5 games back – but could not overcome the Yankees. However, Philadelphia would take the AL pennant the next three seasons, winning the World Series in 1929 and 1930.

Eight years after his final season, the Baseball Writers’ Association of America would honor Cobb in 1936 by electing him to the new Baseball Hall of Fame as a member of the inaugural class. He appeared on 98.2 percent of the ballots, making him the highest vote-getter and setting a mark that would last 56 years.

Matt Rothenberg is the manager of the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Philadelphia A’s trade Jimmie Foxx to the Boston Red Sox

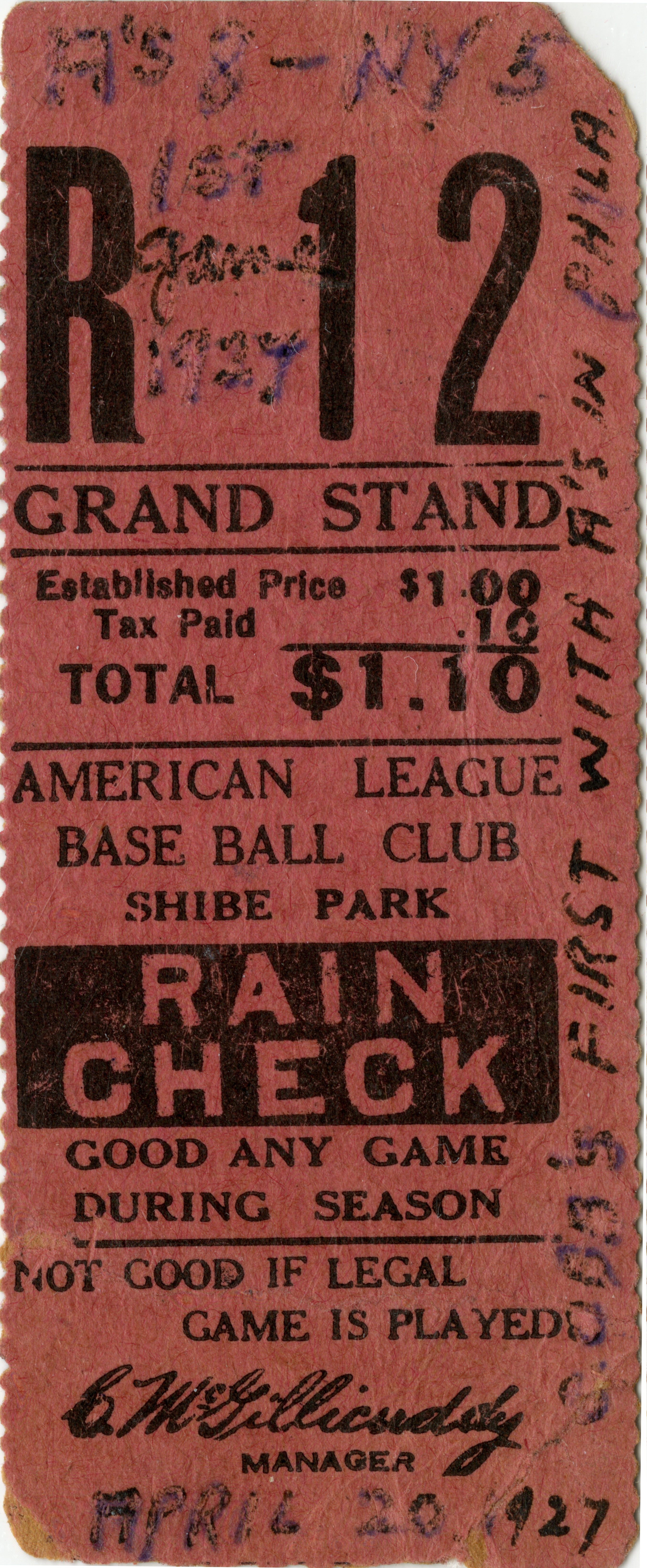

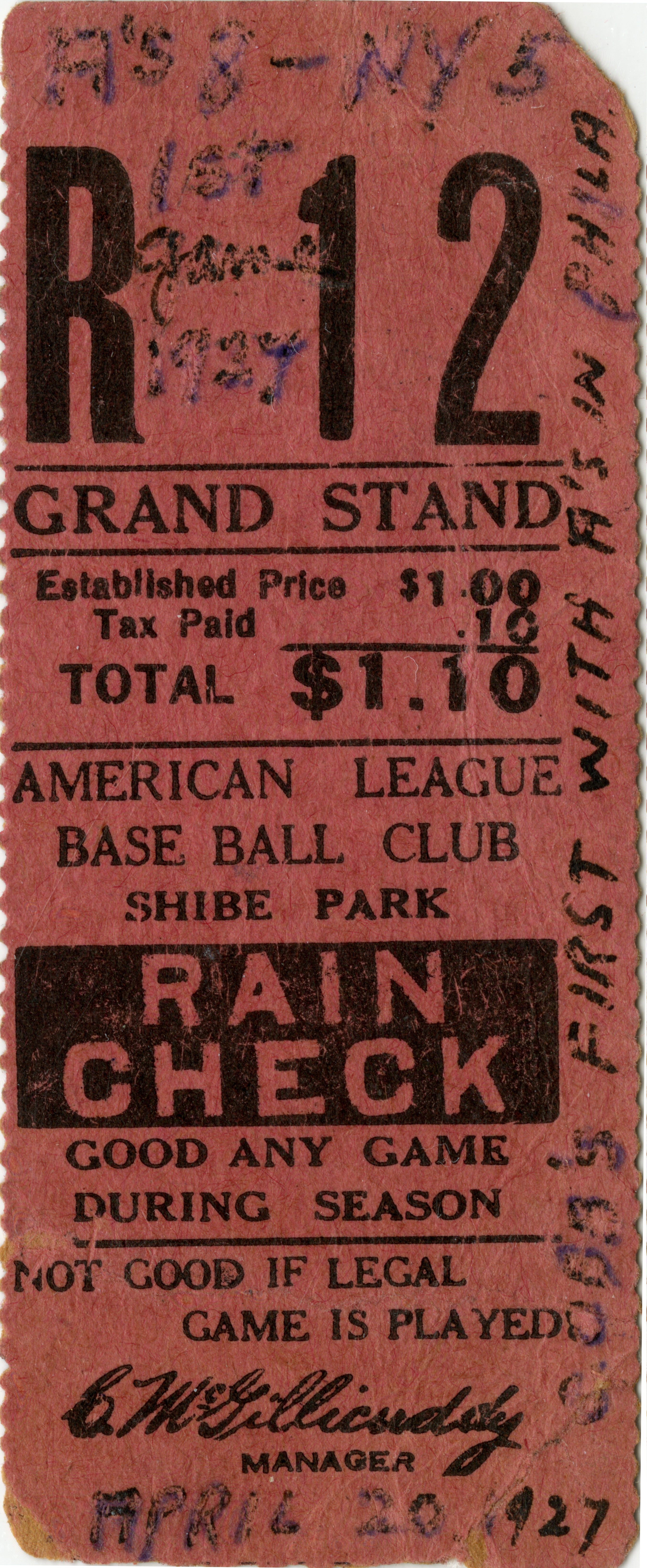

Just the Ticket for Cobb

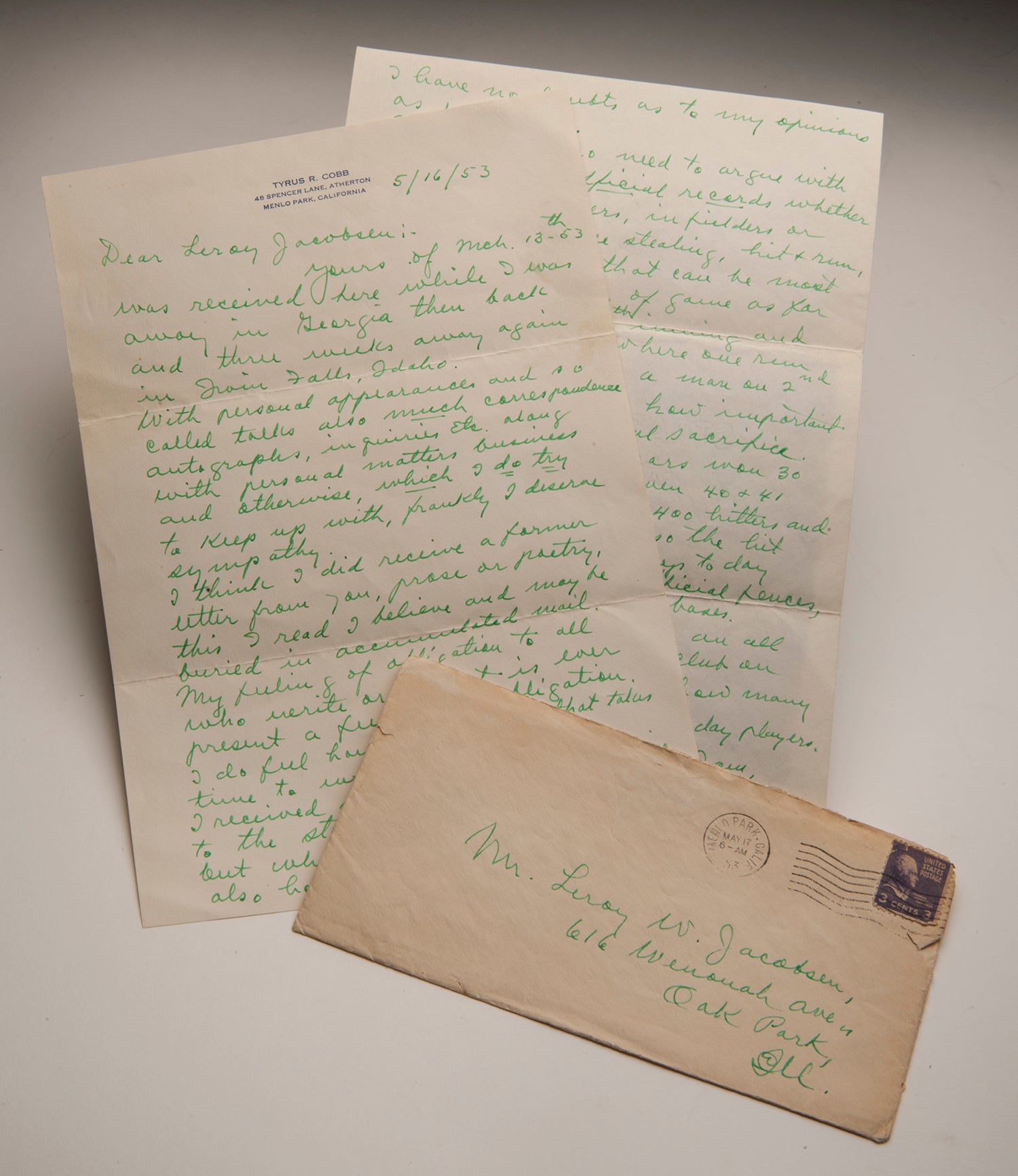

#Shortstops: Letters from Ty Cobb

Philadelphia A’s trade Jimmie Foxx to the Boston Red Sox

Just the Ticket for Cobb