- Home

- Our Stories

- Jake Daubert: A miner in the majors

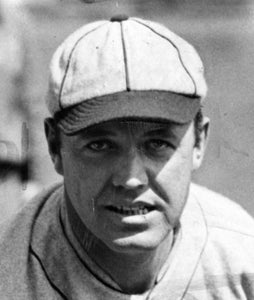

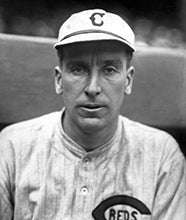

Jake Daubert: A miner in the majors

In some ways, Jake Daubert never left the coal mines. He carried reminders on his hands. “Look at these hands,” he once said to a reporter. “See those black marks? That’s from mining, and even now, when I look at them, I sometimes . . . fear that all my success is a dream and that I will wake up in the darkness of the mines again.”

Jacob Ellsworth Daubert was born on April 17, 1884 in Shamokin, Pa., and from an early age he knew what he would be: A coal miner, like his dad and his two older brothers. "It’s in my family," he once said.

He began work at age 12 as a breaker boy, sitting on a wooden plank over a chute of tumbling coal, reaching down to separate slate from coal with his bare hands. Later he shored up “caving roofs with timber” and drove mules hauling cars of coal until he became a regular miner. Starting at 16 and for the next six years, Daubert swung a sledgehammer in dark, jagged tunnels, a thousand feet underground—10 hours a day, 250 days a year.

On the other days—weekends and holidays—he played baseball. By 1906, he played in a semi-pro league made up almost entirely of miners, but he caught the eye of the nearby Kane Mountaineers, a Class D team in the Interstate League. When he was offered a contract, Daubert was hesitant to give up the full-time pay of mining, and he doubted he had the ability to last long in professional baseball, but his wife of three years convinced him he should try.

So at age 22, Jake Daubert became a professional baseball player.

Daubert reached the Major Leagues in 1910, signing a $2000 contract with Brooklyn. The first thing he did was tell his dad to put down his sledgehammer and retire; fifty-seven years in the mines was more than enough (his mother had died when Jake was young).

Daubert hit .307 with Brooklyn in 1911 and played superior defense at first base, drawing comparisons with Hal Chase. But for Daubert, baseball remained an uncertain career. Always unassuming and straight-forward, he was quick to dismiss his own accomplishments:

[.307] was my last season’s batting average, but I am not a three hundred hitter. I would like to think that I am, but I have no reason to. . . . Everything broke just right for me. To tell the truth, I was very lucky, for I know that my average batting gait is nowhere near three hundred. I think I am about a .250 hitter. I cannot claim to be any more, but of course I shall always do my best.

Nevertheless, he hit .308 the following season and then led the National League at .350 in 1913. After that season, he was voted “the most important and useful player to the club and to the league,” winning the Chalmers Award, and with it, a Chalmers automobile (Daubert’s first thought was one of anxiety: He’d have to learn to drive). He led the league again the following season, but he still downplayed his success:

I cannot claim that I have really earned my success. I am not trying to say, of course, that success is anything unusual, but to me it seems great compared with what I hoped to do when I was a coal miner. It is so much better than anything I supposed possible for me that I cannot believe it is merely the result of my own efforts. True, I have worked hard at all times and have always played my best. But I consider myself a very lucky man.

Daubert by now had a reputation for being tight with money; few knew that he was supporting his father, as well as his wife and two children. He knew a baseball career could be short, so he did all he could to provide for his family. When the rival Federal League offered him a contract in 1914, Daubert leveraged a $9000 per year, four-year deal from Dodgers owner Charles Ebbets, a lengthy contract for the time. He also began outside business projects, such as Jake Daubert Cigars, which were sold in Brooklyn and back home in Pennsylvania, and investing in a movie theater. But as he told a reporter, “I only know two things, mining and baseball.” So he started a coal washery business, and bought a coal dredging barge.

The year 1916 brought professional triumph and personal tragedy. As team captain, he led the Brooklyn Dodgers to their first World Series. But a mining accident took the life of his brother Calvin.

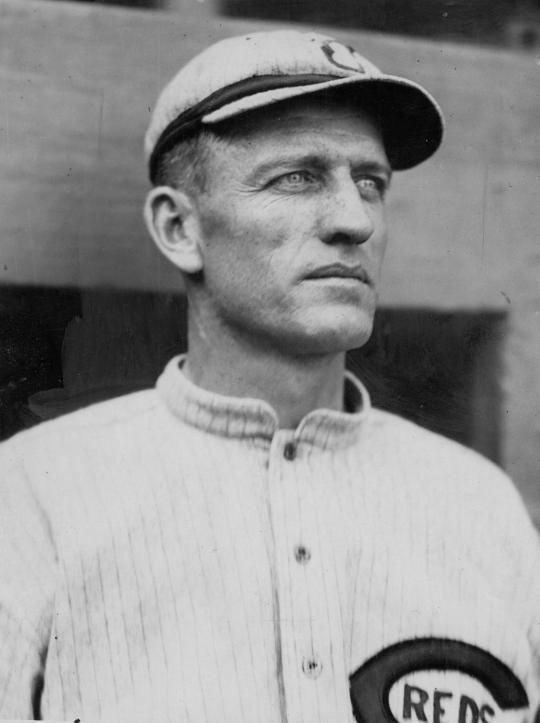

In 1918, Major League Baseball stopped the season a month early because of the Great War. Charles Ebbets, a penny-pincher himself, didn’t pay the players for the last month of their contracts. Daubert, long an advocate for player rights, sued Ebbets (in 1913 he had the gumption to petition the owners to provide each new player a free uniform, excluding shoes. The petition was ignored). Ebbets angrily traded Daubert to the Cincinnati Reds before the verdict, which was eventually given in Daubert’s favor.

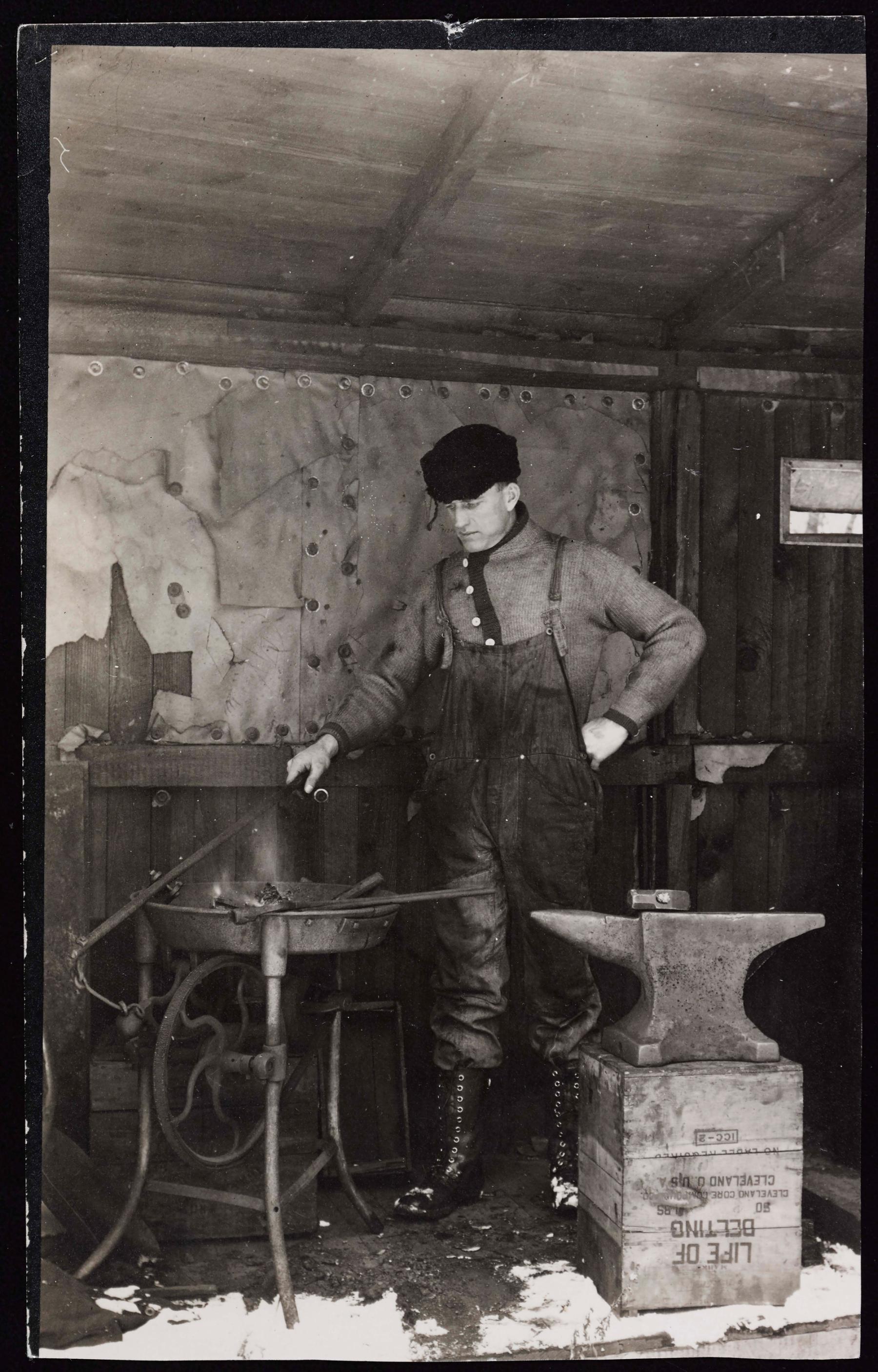

It is from this time—the war years—that a remarkable photograph of Jake Daubert appears. It was recently digitized from a family scrapbook that had been donated to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum by Jake’s son, George Daubert. It shows Daubert not in a baseball uniform, but in the rugged clothes of a man working with coal.

On the back of this image, someone has typed "1917 Daubert coal dredge pumping coal from Schuylkill River to aid war effort. Coal shipped to steel mills." The person on the dredger is unidentified. BA-SCR-219-2-002. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

This image of was included in an envelope of four pictures, part of a scrapbook donated to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum by Jake Daubert's son, George Daubert. Written on the back in pencil script is "Jake Daubert at Coal Washery." BA-SCR-219-2-006. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

He stands in a shed, wearing a heavy, woolen shirt, buttoned up to his neck and thick work overalls, stained from coal and dirt. Snow still sticks to his black boots, laced up halfway to his knees. He holds an iron rod over a fire. An anvil, shiny from years of wear, sits in the foreground. Handwritten on the back of the photograph is “Jake Daubert at Coal Washery.”

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

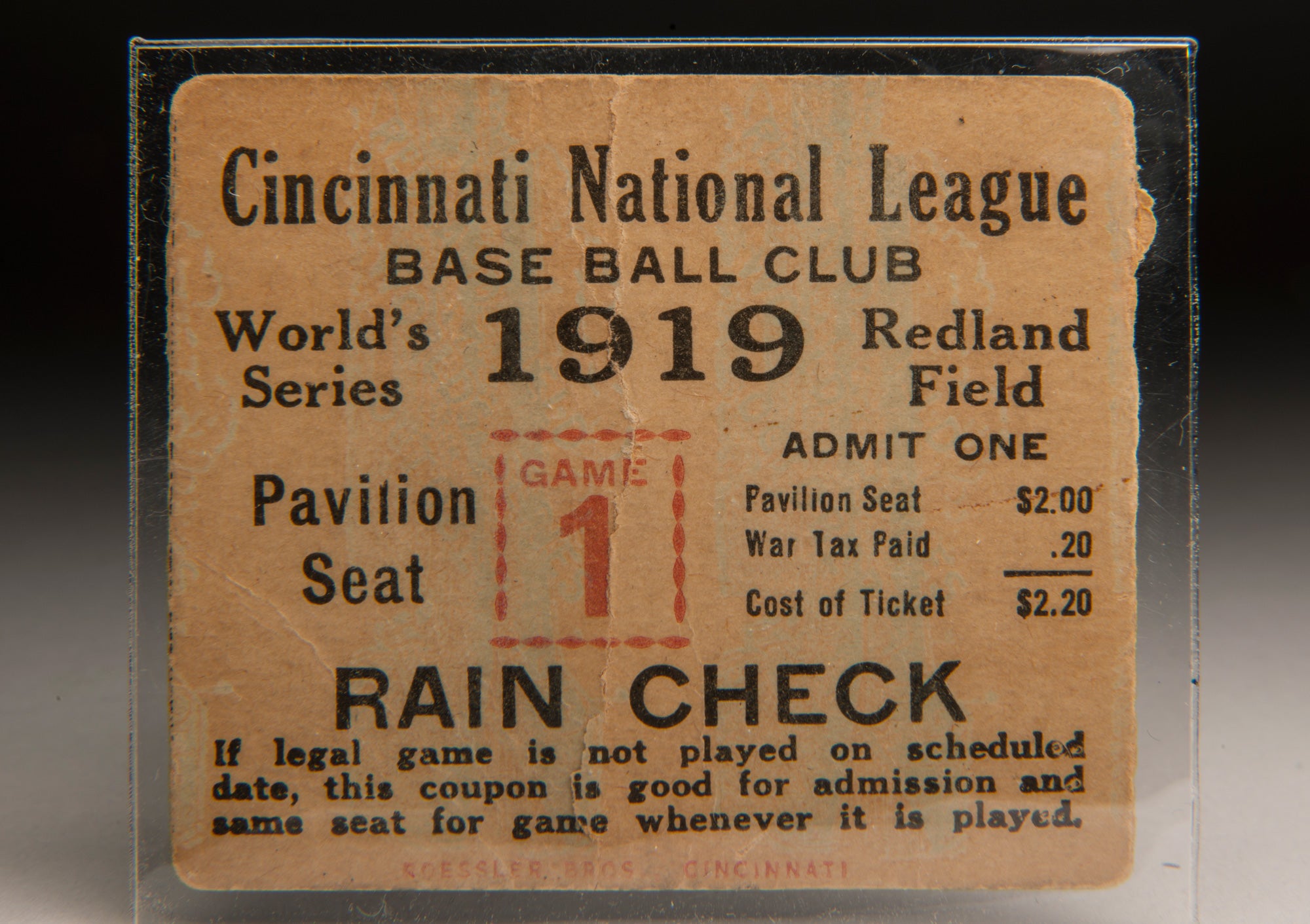

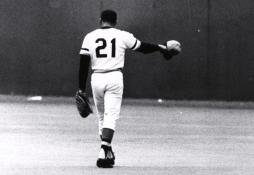

His first season in Cincinnati, Daubert was appointed team captain and led the Reds to their first World Series Championship, though most baseball fans know more about the losers of that Series, the 1919 Chicago White Sox, than the winners.

When he was asked to explain his hitting success, he went to the coal mines for an analogy—swing a sledgehammer enough times, and soon you can hit the iron peg every time. He also attributed his longevity to the mines: “Whatever you can say against it,” he wrote in an article in Baseball Magazine, “breaking rock and shoveling coal in the dark, certainly does harden a fellow’s muscles . . .”

Always a fast runner, at age 38, he led the league with 22 triples (still the most triples hit by a player 38 or older) and hit .336 (and 11th best batting average by a player 38 years old or older). Daubert continued to play sparkling defense at first base, being called “one of the most brilliant first basemen the game has ever known.” He used his bat-handling abilities to accumulate sacrifice hits—he still ranks second all-time with 392 successful bunt attempts. In 15 Major League seasons, Daubert hit over .300 10 times, finishing with a .303 career mark. Eight times, he was voted as Baseball Magazine’s All-Star first baseman.

After the 1924 season, Daubert had one year remaining with the Cincinnati Reds, though he was fielding a three-year offer from the Pittsburgh Pirates. But that September, Daubert experienced abdominal pain. The doctors suspected gallstones and appendicitis, and they operated on him on Oct. 2.

He never recovered from the surgery, passing away on Oct. 9, 1924. Jake Daubert died with family and teammates by his bed, thereby avoiding his greatest fear:

It was only yesterday that I thought I would always be a coal miner. I never expected to be anything else . . . . It doesn’t seem right that I should be so fortunate . . . . I can’t help feeling it will all slip away from me some day and that I shall finish my life where I started: in the coal mines.

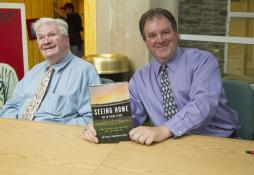

Larry Brunt is the Museum’s digital strategy intern in the Class of 2016 Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program for Youth Leadership Development