“Any one can recommend a ballplayer, but it takes real judgment to reject ‘em.”

- Home

- Our Stories

- In Search of...History

In Search of...History

They languished in baseball’s shadows for decades -- the talent hunters for big league baseball. But the history of scouts features as many wonderful stories and people as the game itself.

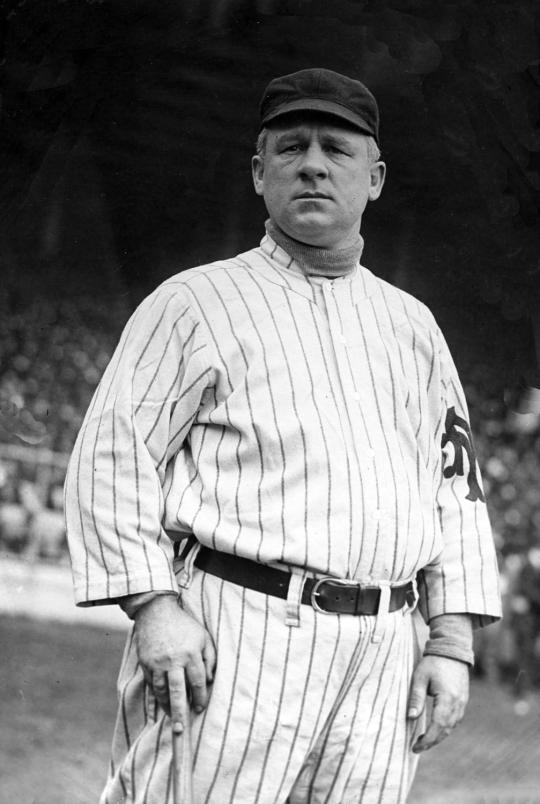

Nobody knows for sure who should wear the mantle as the first baseball scout. There is a great deal of support for Timothy Paul “Ted” Sullivan, who was born in Ireland in 1851, migrated to Illinois as a young man and befriended Charles Comiskey in his playing days. He later delivered to the future White Sox owner many players as well as providing talent to other teams in both major leagues. According to baseball historians, Sullivan probably served at one time or another in every scouting role from the grassroots birddog to area scout to cross-checker. He also organized the All-American world baseball tour in the offseason of 1913-1914 led by Comiskey and the New York Giants’ John McGraw.

If direct appearance on a club payroll is the guidepost, then Larry Sutton may win the prize. Sutton was born in 1858 in Oswego in upstate New York. According to a profile by the late scout Jim Sandoval in the recent anthology, Can He Play?, Sutton became hooked on baseball at the age of 10 while selling programs when the Cincinnati Red Stockings came to town. A newspaper printer and proofreader by trade, Sutton was hired by Brooklyn Dodgers owner Charles Ebbets in 1909 and delivered to him future Hall of Fame outfielder Zach Wheat as well as Casey Stengel.

Sutton’s evaluation of young Stengel was a classic: “Good hands, good power, runs exceptionally well, nice glove, left-handed line drive hitter. Good throwing arm. May be too damn aggressive, bad temper.” (quoted from Kevin Kerrane’s marvelous book on scouting, Dollar Sign on the Muscle)

Sutton could always be spotted at games carrying an umbrella, prepared for the capriciousness of baseball weather on any given day.

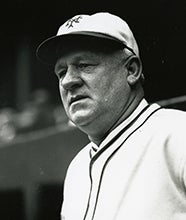

For pure color in the early years of scouting, there’s Dick Kinsella, John McGraw’s first paid scout. Born in 1864 in Springfield, Ill., Kinsella became a prominent local businessman and well-connected politically. Because Kinsella operated a paint store, writer Damon Runyon, author of the immortal “Guys and Dolls” and a fascinated observer of the New York sporting life, dubbed Kinsella “the varnish king of Springfield.” Kinsella was also known as “Sinister Dick” because of his dark complexion and “eyebrows (that) looked like fright wigs,” New York sportswriter Tom Meany quipped.

Among Kinsella’s discoveries for McGraw were future Hall of Fame second baseman Frank Frisch, who came directly from the Fordham University campus in the Bronx, and Hall of Fame southpaw Carl Hubbell, who he rescued from the minor leagues after the Detroit Tigers thought he would never master the screwball.

There probably can be no final resolution to the debate about the first scout but what is very clear is that as baseball majestically rose to its perch as the National Pastime in the first decades of the 20th Century, the romance and importance of the baseball scout was already attracting wide attention.

In an article for The Saturday Evening Post that came out during the 1913 World Series, the writer, an anonymous scout, described the men in his profession: “Grizzled old ex-big leaguers they were mainly, mysterious and whispery, for scouting was . . . considered a gumshoe game.” The scout described himself as a pessimist because he believed that finding great players was as rare as discovering great actors and literary geniuses. “Any one can recommend a ballplayer, but it takes real judgment to reject ‘em,” he insisted.

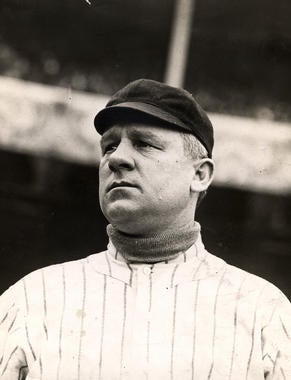

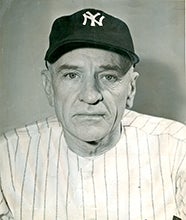

Cy Slapnicka is another example of the “colorful” scout. He was born in 1886 in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, to parents of Czech and Bohemian heritage. He pitched in the obscurity of the minor leagues for 15 seasons, arriving in the majors only long enough to win one game for the Pirates in 1918. During the offseasons, he worked at many jobs including acrobat and juggler in vaudeville shows. When Cy began scouting for the Cleveland Indians in 1923, some critics felt that he was using his juggling background nefariously when signing amateurs for very little money and releasing them if they failed to develop.

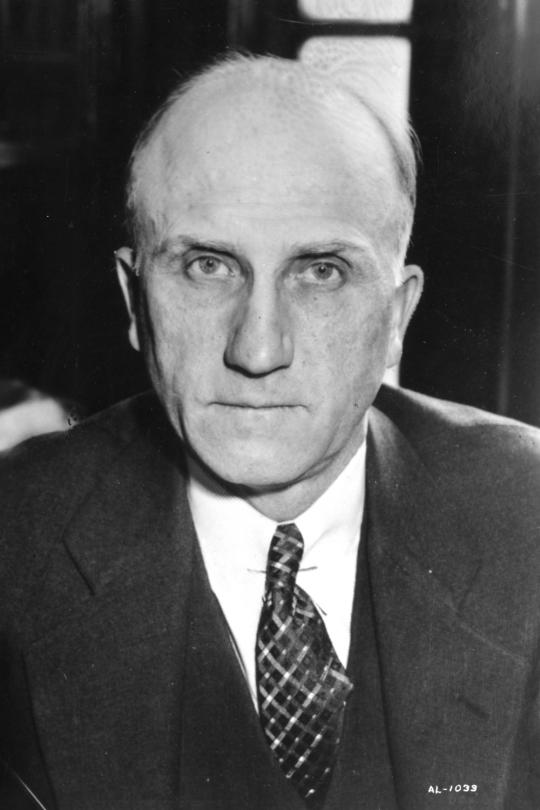

Baseball’s first commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis looked sternly at these manipulations by Slapnicka and the more voluminous efforts of Branch Rickey, who was building a huge player development empire. When Slapnicka became Indians general manager in 1935, he almost lost teenage sensation Bob Feller because he placed the pitcher on a minor league roster for which he never played. But Landis tempered his wrath when he realized that Feller of Van Meter, Iowa, wanted to play for the organization of his fellow Iowan Slapnicka.

In 1937 Slapnicka signed another promising player, speedy Oklahoma-born outfielder Hugh Alexander. The youngster, who had defeated the legendary Jesse Owens in high school track meets, appeared in seven big league games at the end of the 1937 season. But tragedy struck during the off-season when he lost a hand in an oil rig accident.

Acting very paternally, Slapnicka immediately hired Alexander at age 20, making him the youngest scout in baseball history. Determined to make good in his new profession, young Alexander read Dale Carnegie’s popular best-seller, How To Win Friends and Influence People four times. He gratefully received a tip from Hank Iba, the legendary Oklahoma A. & M. basketball coach who also coached baseball, and signed Allie Reynolds, the future star New York Yankees starter and reliever. Reynolds became one of the first signings of Alexander’s career – one that stretched over 60 years.

Another colorful scout in this period was Joe Cambria of the Washington Senators. Just as Hugh Alexander drew on his close association with Cy Slapnicka, Cambria became very close to Washington’s Clark Griffith, one of the less-rich owners who needed a steady supply of good cheap talent.

Born in Messina, Italy about 10 years before the turn of the 20th Century, young Cambria settled with his family in the Boston area. He played outfield for many minor league teams though never came close to making the majors. After the World War I, Cambria went into the laundering business in Baltimore and became a part-owner of both white and black baseball teams in the Maryland city.

One of the ironies of Cambria’s story is that though his lineage was Italian, he became famous for building a Cuban player pipeline to the Senators. He actually spoke very little Spanish but starting in 1933 and for nearly the next 30 years, cigar-smoking “Papa Joe” became a magnet for hungry and ambitious Cuban players. He sent dozens of low-paid prospects from the island nation to the cash-poor Washington owner whose team made the World Series in 1933 but still lost money.

Among future star pitchers sent to Washington from Cuba were Camilo Pascual and Pedro Ramos, future major league manager Preston Gomez, and first baseman Julio Becquer who later settled in Minnesota where the Senators moved before the 1961 season. Becquer told me during an encounter in the summer of 2011 that after Fidel Castro took power in 1961, Calvin Griffith, nephew of Clark Griffith and his uncle’s successor as owner, arranged for Becquer’s wife to emigrate from Cuba to join her husband.

When Landis died at age 77 during Thanksgiving week of 1944, a new more impersonal age was about to emerge in baseball. With a baseball boom expected in the first post-World War II season of 1946, new flush and impatient owners were coming on the scene like the Phillies’ Bob Carpenter, an heir to a DuPont family fortune. He lavished high five-figure bonuses on young pitchers Robin Roberts and Curt Simmons who contributed to the Phillies 1950 pennant, its first since 1915. But the absence of investment in a farm system soon caused the Phillies to return to their previous second-division status.

When Branch Rickey moved to Pittsburgh after the 1950 season to attempt the rebuilding of a barren Pirate farm system, he began to turn his attention to Latin America. Like Joe Cambria, Rickey’s top scout Howie Haak was not fluent in Spanish. It is said that he only knew four words: “Throw Hard, Run Fast.” But the onetime pre-med student from Rochester, N.Y., knew how to find the diamond in the rough and how to look deep into a player’s heart to see how he might or might not develop. After the 1954 season, the Pirates plucked young Puerto Rican outfielder Roberto Clemente from the Dodger farm team in Montreal. Soon the pipeline to Latin America was contributing to World Series championships in 1960 and 1971 ending a Pittsburgh pennant drought dating back to 1925.

As the major leagues expanded to 26 teams by 1977, it was becoming clear that the age of the flamboyant scout and the paternal relationship between many owners and players was dying out. There had been grumbling that too much bonus money was being lavished on young amateurs but the attempt in the 1950s to force “bonus babies” receiving more than $4,000 to remain on the major league roster did not work out. It largely kept young talent inactive when it would have been best served getting experience in the minor leagues.

A revolutionary change occurred in June 1965 with the introduction of the first amateur free agent draft, modeled after the pro football draft that had been so successful in giving less successful teams the first chance at the best new talent.

The draft meant the end of the most creative kinds of competitive scouting and further broke down the tie between the player’s family and the scout.

“We knew that we were part of something bigger than ourselves.”

Several teams strongly opposed the idea of the draft. The Phillies’ scouting director Paul Owens, later general manager, told Kevin Kerrane, “I felt like a race car driver with a governor on his engine.” Traditionalists complained that bad teams should not be rewarded for bad management.

Yet the draft was here to stay and the drive for equalization of talent took an additional measure in 1974 with the establishment of the Major League Baseball Scouting Bureau. Every player would now be scouted by a central office with information available to every team. Again, not every team wanted a part of this new system but by the mid-1980s then-commissioner Peter Ueberroth ordered that every team must join and pay its share of expenses to the Bureau.

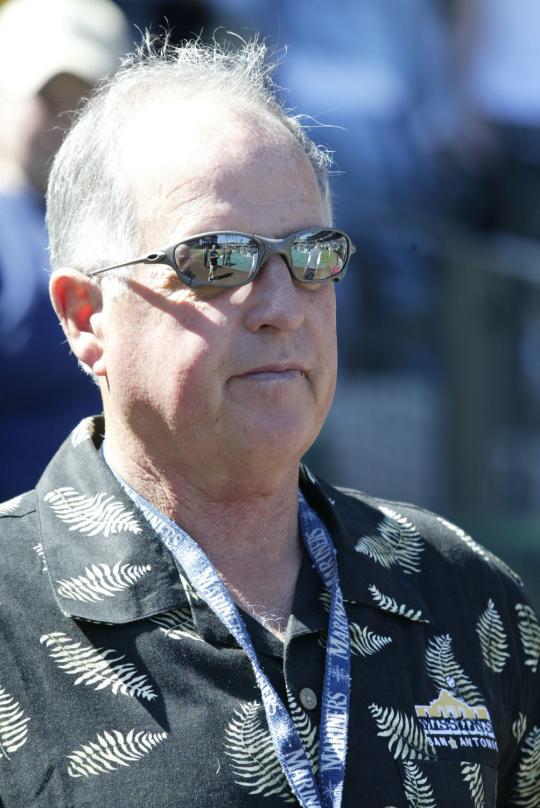

Despite the fears of the oldtimers, it is clear that the human side of baseball scouting will never go away. The thrill of the hunt will always remain. During the acceptance speech of Pat Gillick into the Hall of Fame in July 2011, he paid special homage to the work of the scouts who battled with each other for players but always remained collegial.

“We knew that we were part of something bigger than ourselves,” Gillick said.

Lee Lowenfish is an award-winning baseball author

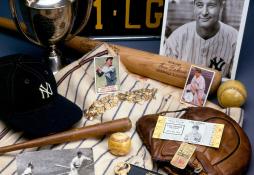

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

Baseball, boxing intersected famously at Forbes Field in 1941

A Classic to Remember

Former Seattle Pilot Ray Peters Visits Hall of Fame

Time to PLAY Ball

#GoingDeep: Cristóbal Torriente Bests the Bambino

Hall of Fame Weekend 2015 to Feature Inductions of Biggio, Johnson, Martinez and Smoltz, July 24-27 in Cooperstown

Hall of Fame Celebrates Baseball’s Love of Bubble Gum by Teaming Up with Big League Chew

BA MSS 67, Folder 21, Corr_1957_1_11b

01.01.2023