- Home

- Our Stories

- Steve Rippley Touches Home

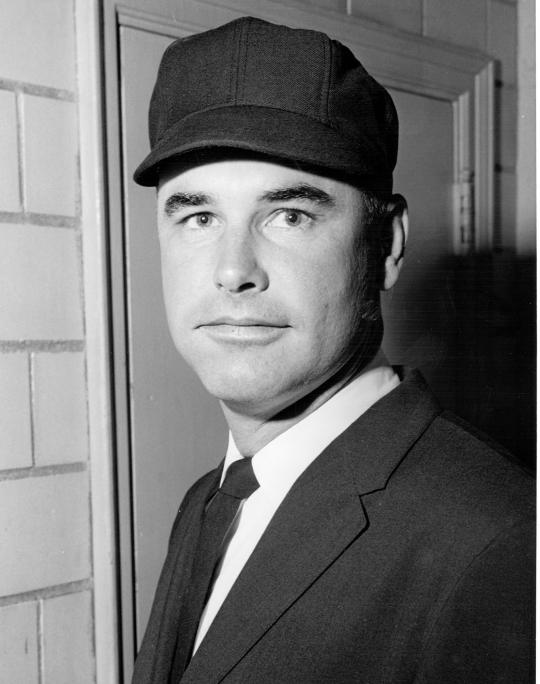

Steve Rippley Touches Home

During his Induction speech in 2010, revered National League umpire Doug Harvey told the crowd that true baseball fans needed to visit Cooperstown -- the home of baseball -- and that he’d make sure those fans would “touch home before the end of the game.”

This past Friday, Sept. 2, Harvey could count his senior circuit umpiring colleague Steve Rippley, among those who did.

“My wife and I have had it on the bucket list to get back here, and we were able to get it done,” he said. Rippley had once worked a Hall of Fame Game, but was whisked through the museum quickly, and didn’t recall much.

Rippley, who worked a total of 2,513 regular season and 50 postseason games for National League (1983-1999) and Major League (2000-2003) staffs, enjoyed a behind-the-scenes tour of the Hall of Fame, along with his wife Donna and their friends. Curator John Odell discussed the array of artifacts on display for the group, including some items which were especially of interest for the longtime arbiter.

One such artifact was an umpire’s indicator from the 1887 season – a year in which five balls counted as a walk, walks counted as hits, and four strikes were necessary for an out. Such rule changes gave batters more of an advantage.

“It worked, in that there was a lot more offense,” Odell explained, noting that in today’s game, such changes would be tested in the minor leagues or in spring training exhibition games. “It didn’t work in that there was way, way too much offense. It threw the balance out of balance.”

When asked if he was glad the rules were changed back to the customary four balls and three strike system, Rippley answered that if they hadn’t, he “would’ve retired a long time ago.”

With a few more umpiring artifacts on the table, Odell deferred to Rippley. The first was a pair of “plate shoes,” worn by home plate umpires – in this case ones used by Harvey.

“I’ve seen these a lot. I’ve seen these in action,” Rippley noted, when told they were used by the man called “God.” “It was more of a steelworker’s shoe when I first broke in, but the athletic companies make these now. It has a steel toe, if you get hit by a foul ball,” and there is a steel plate which covers the top of the foot.

He continued, “If you got hit by a foul tip, you didn’t break a nail or break your foot. They were very clunky.”

Also on display was an umpire’s mask, used by Harvey, and which featured West Vest technology developed by another of Rippley’s National League umpiring colleagues, Joe West.

“This is Joe West’s product, the West Vest. He has a patent on that. [West] sold the patent to the chest protector and the shin guards to Wilson (sporting goods),” Rippley said, as he discussed changes in umpire gear.

When Odell showed the group one of the bat racks, Rippley asked if the Hall of Fame had the bat Mark McGwire used for his record-breaking 62nd home run in 1998.

Why did Rippley ask? Because he happened to be the home plate umpire that evening in St. Louis.

It was one of many memorable moments in a 21-season major league umpiring career, which was preceded by nine years of climbing the ladder in the minors.

“For an umpire, it’s always your first game in the big leagues,” Rippley said about his most special moments. “Then it’s working your first All-Star Game. … Then, obviously, it’s your first playoff (game) and your first World Series.”

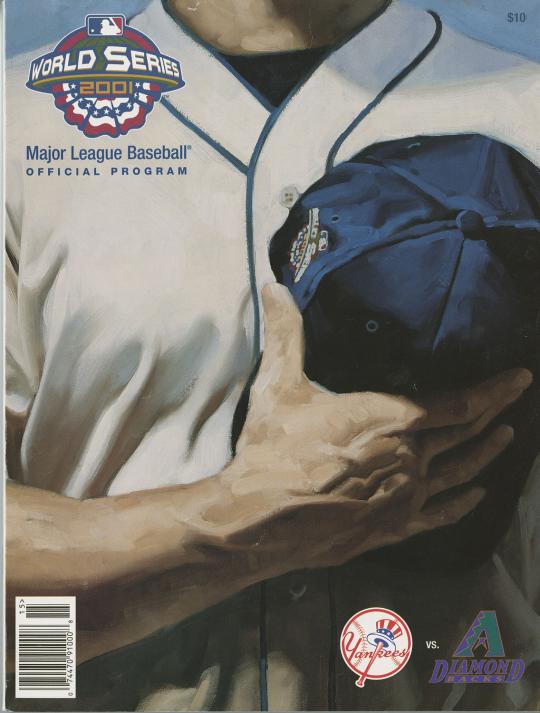

One of the most memorable moments for Rippley was the 2001 World Series, one of three Fall Classics he officiated, and the only one in which he was a crew chief. He still has his uniform and other memorabilia from that series.

“What was most unique was that the 2001 World Series was centered around 9/11, and it was delayed,” he remembered, as the entire series was filled with great emotion, especially in New York. “They had the bomb-sniffing dogs and the security was unbelievable that surrounded the whole thing.”

Rippley, who, as home plate umpire, watched Midre Cummings and Jay Bell score the tying and winning runs in the bottom of the ninth inning in Game Seven, continued, “The whole series [was] an instant highlight tape because I believe of all three games in New York – when they were trying to make the comeback (in the series) – two [of them] went extra-innings and all three were one-run games. It was unbelievable.”

On the opposite end of the emotional spectrum, Rippley worked the July 25, 1990, doubleheader in San Diego between the Padres and Reds, the games before which Roseanne Barr performed her rendition of the national anthem.

“I was standing next to Bruce Froemming – he was the crew chief at the time – and when she was butchering the whole song, Bruce mentioned, ‘I’m thinking about going out and taking the microphone away from her,’” Rippley said.

The Retrosheet website counts Rippley as having 56 ejections under his belt. He was behind the plate in Atlanta on August 12, 1984, when 17 of those ejections occurred that afternoon. The four-game series between the Braves and Padres devolved into a beanball war, as San Diego’s pitchers went after Atlanta’s starter, Pascual Pérez, who hit Alan Wiggins to lead off the game.

“The night before … (Pérez and Whitson) had been conversing after the third (bunt) base hit. So I knew, the next day, that the first pitch that [Pérez] hit [Wiggins] with was for the night before,” Rippley recalled. “Had they come out and hit Pérez on the first at-bat, I think it would have been a non-issue. But because they kept missing him, it mushroomed into 17 ejections.

“In that case, I had to write 17 ejection reports. At the time, we didn’t have online [submissions], so everything had to be written up and faxed to the league office.”

One of his fellow umpires during that beanball-filled game – the crew chief, John McSherry – was a close friend of Rippley’s, having umpired together in the National League for 13 seasons. The two were scheduled to begin the 1996 season together on April 1 in Cincinnati when tragedy struck.

Rippley, who was on the field as part of the umpiring crew that day, called it one of the “toughest days of [his] life.”

“That day was tough obviously, and the next day is when we did play [the game] but it was probably the toughest day of my life trying to concentrate on the field,” he said. “It was a tragedy; it was tough to get through it. I had worked with John, and I had taught at umpire school with John, so we were fairly good friends.”

Rippley spent offseasons as an instructor, then head instructor, at Joe Brinkman’s umpiring school. Many of his students are now MLB umpires, including several who are crew chiefs.

“All that tells me is that I’m getting old,” he joked.

Now semi-retired in Florida, Rippley remains active as an umpire observer for Major League Baseball at games played at Marlins Park in Miami, filing reports and watching game film to assess the umpires. Otherwise, he enjoys traveling and spends a good deal of free time on the links.

Yet, it might have been a life incomplete had he himself not had the opportunity to touch “home.”

After all, his colleague Harvey is still watching to make sure.

Matt Rothenberg is the manager of the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Umpires Break Through Glass Ceiling

Umpires Break Through Glass Ceiling

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

Pick a Pair: Hall of Fame Class of 2016 makes draft history

Cubs trade Hoyt Wilhelm to Braves for Hal Breeden

Making of a Legend

Hall of Fame Celebrates World Series Weekend, Honoring San Francisco Giants, Aug. 1-2 in Cooperstown

The Hall of Fame Celebrates Royals’ World Series victory

“Old Pete:” How Grover Cleveland Alexander Got His Nickname

1947 Hall of Fame Game

Pedro comes to Cooperstown

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bob Watson

1963 Hall of Fame Game

Joe DiMaggio makes his big league debut, recording three hits in the Yankees’ win

01.01.2023