- Home

- Our Stories

- With deliberate speed, the 1950s saw the reintegration of the white major leagues

With deliberate speed, the 1950s saw the reintegration of the white major leagues

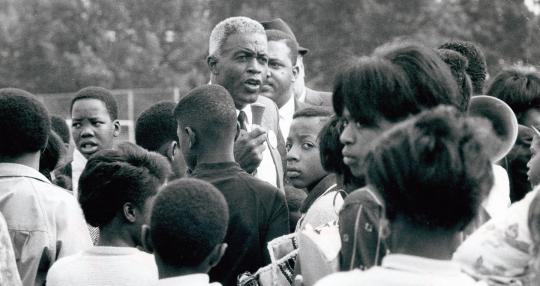

Even years after Jackie Robinson, Larry Doby, Hank Thompson, Willard Brown and Dan Bankhead reintegrated the white major leagues, the United States was still under the dogma of “separate but equal” imposed by the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision. This doctrine legalized racially segregated public facilities, so long as the facilities for Black people and whites were equal. As Baseball Writers’ Association of America Career Excellence Award winner Sam Lacy unequivocally said: “Some people were more equal than others.”

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

The 1896 ruling constitutionally sanctioned laws barring Black Americans from sharing the same buses, schools and other public facilities as whites — known as “Jim Crow” laws — and established the “separate but equal” rule that stood for the next six decades.

Overturned by the 1954 Brown v. the Topeka (KS) Board of Education decision, the Supreme Court ordered American schools to be integrated, using the operative words “with all deliberate speed,” which was purposely vague — allowing local school boards to delay, obstruct and generally slow the process of integrating Black and white students.

This built-in ambiguity gave segregationists the opportunity to strategize resistance. Historically, segregated schools and public facilities had been inherently unequal, despite the provision to provide all citizens with equal protection under the law guaranteed in 1868 by the Fourteenth Amendment.

Unquestionably, sports, especially baseball, have been a barometer for social change in America, as it is essentially a game of resilience, just like real life. One precursor to social change in America began with the reintegration of the National League.

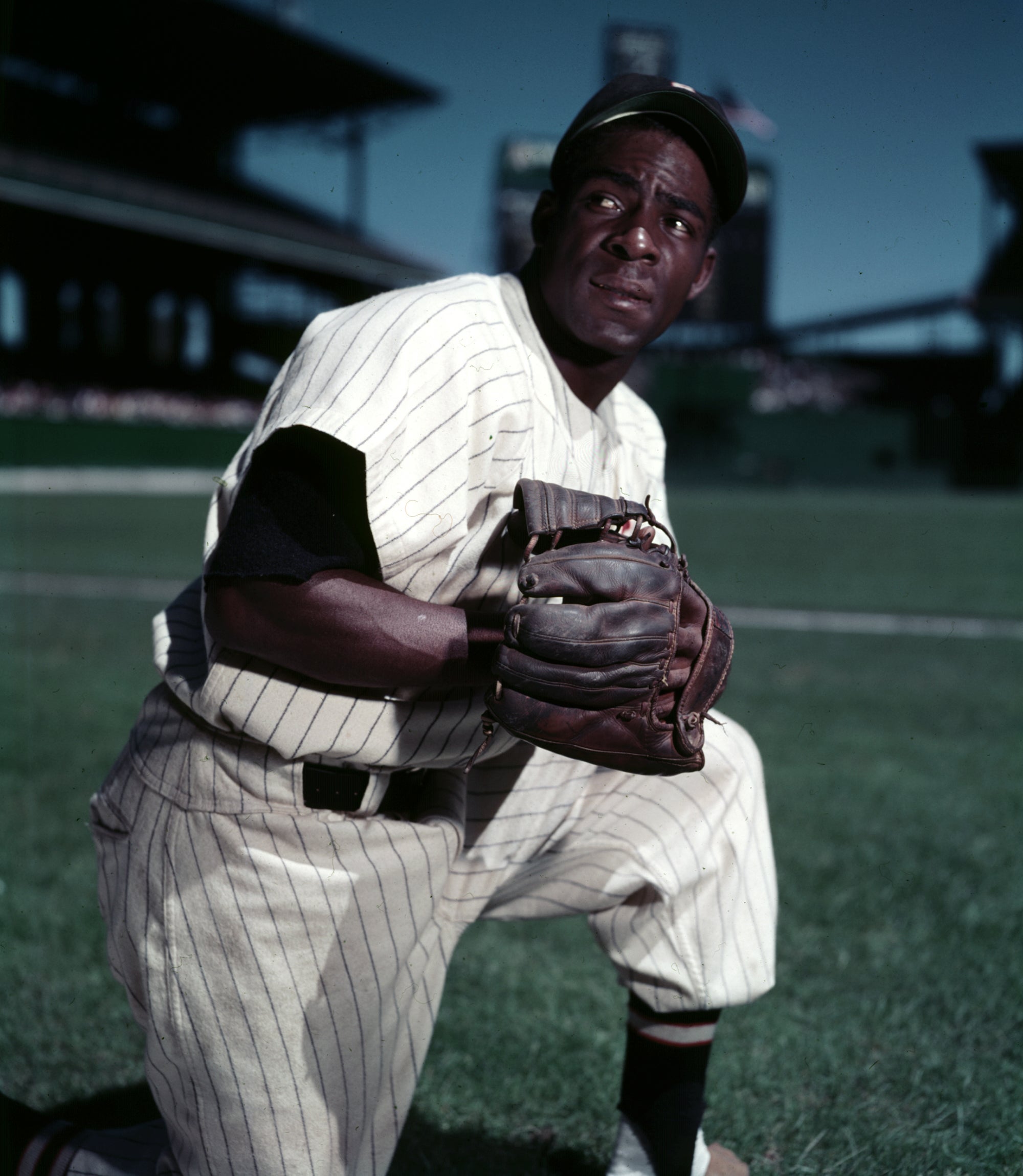

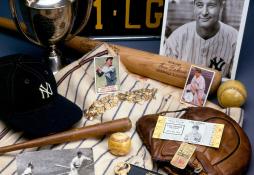

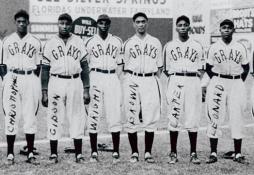

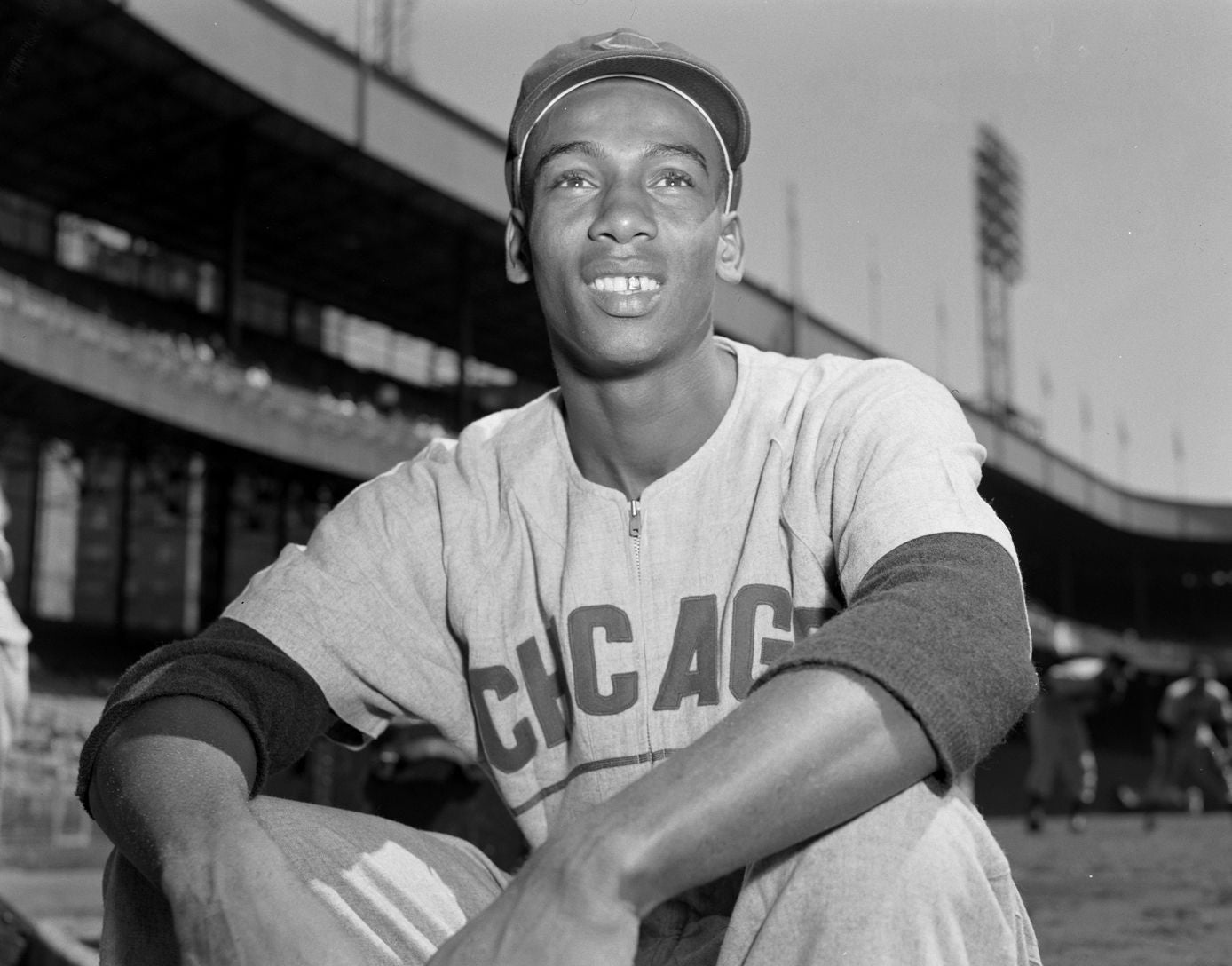

Stars like Doby, Thompson, Brown, Bankhead, Satchel Paige and Ernie Banks were fast-tracked to the AL and NL from the Negro Leagues. Meanwhile, the Brooklyn Dodgers bolted to the front of the diversity pack with seven Black and Latino players on the team by 1956, Jackie Robinson’s last season in the pros. During Robinson’s time, the Bums arguably became Black America’s favorite team.

Still, as noted by several media outlets, the Dodgers failed to honor Robinson’s agreement with the Kansas City Monarchs when no compensation was offered for his service. To avoid reparations, Branch Rickey’s radical rhetoric about Negro Leagues teams operating “in the zone of a racket” implied that their team owners were mostly number bankers with criminal intent.

However, research reveals the primary occupations of owners encompassed many professions — from bowling alley operator (Tom Baird) to postal clerk (Ed Bolden), undertakers (Robert Cole, Robert Lewis Sr.), bail bondsman (Tom Bowser), night club owner (Soosa Bridgeforth), restaurant owner (John Connor), pool hall owner (Hugh Cherry), boxing promoter (Gus Greenlee), service station owner (Rev. John Harden), insurance broker (Tom Hayes Jr.), music store owner (Sonnyman Jackson), taxi company owner (Dr. Richard Kent), blues singer (Gatemouth Moore), hotel owner (Joe Rush), dance studio owner (Colonel Strothers), parking garage owner (Sam Sheppard), realtor and chauffeur (Abe Manley), and the Martin brothers’ employment in the medical fields of dentistry, general practitioner, pharmacist and hospital administrator.

During this span, 13 of the original 16 AL and NL teams were integrated, yet the Phillies, Tigers and the Red Sox were still without a Black or Brown face in 1956. Some hesitated to press the integration accelerator.

The stopwatch of senselessness was evident in Roger Kahn’s pivotal 1972 book “The Boys Of Summer,” writing that New York Yankees general manager George Weiss explained at a cocktail party in 1952 why the Yankees were still an all-white team, six years after Robinson signed with the Dodgers.

“I will never allow a Black man to wear a Yankee uniform. Box-holders from Westchester (County) don’t want that sort of crowd. They would be offended to have to sit with [N-word].”

In 1953, the Yankees became the last team yet to integrate to win a World Series when they defeated the Dodgers, who had Robinson, Joe Black, Roy Campanella and Junior Gilliam, in six games. (In retrospect, the 1948 Cleveland Indians, with Doby and Paige, were the first team with color to win a World Series when they beat the Boston Braves in six games.)

Two seasons later, the Yankees signed catcher and first baseman Elston Howard from the Kansas City Monarchs. As Peter Golenbock noted in his classic manuscript “Dynasty,” manager Casey Stengel whined, “When I finally get a [N-word], I get the only one who can’t run.”

One of the last roadblocks to completely integrate the pastime was the Philadelphia Phillies, owned by Robert Carpenter. In Bruce Kuklick’s book “To Every Thing a Season: Shibe Park and Urban Philadelphia,” he emphasized, “As much as he could, Carpenter opposed a [B]lack presence in the majors and certainly at Shibe Park,” and charged that the Phillies “were racist on principle” and “willingly hurt the quality of their teams.” Despite the “City of Brotherly Love” showcasing Black athletes from the NFL’s Eagles, the NBA’s Warriors and the AL’s Athletics with Bob Trice, Vic Power, Héctor Lopez and Harry “Suitcase” Simpson, the Phillies were without color.

After Robinson’s retirement announcement in December 1956, he called out the Phillies, Tigers and the Red Sox in a statement to the Sporting News: “If thirteen major league teams can come up with colored players, why can’t the other three?” In 1957, Cuban shortstop Chico Fernández opened the season with the Phillies, and six days later was joined by John Kennedy, a middle infielder from the Kansas City Monarchs. Kennedy, who had two plate appearances with no hits and no fielding opportunities, was sent to the Class B Carolina League. Former Indianapolis Clowns outfielder Chuck Harmon immediately became Fernández’s roommate.

The Detroit Tigers were owned by Walter Briggs Sr. (from 1935-52) and Walter “Spike” Briggs Jr. (1952-56). Briggs Manufacturing was a vast company, designing cars and supplying various parts and sub-assemblies to automakers that included Chrysler, Ford, Hudson, Lincoln, Packard, Stutz and other models.

So notorious was his refusal to hire Black players that the saying around the Tigers clubhouse and in the factory was “No j*gs with Briggs.” Two years after Tigers ownership changed in 1956, with radio executive Fred Knorr taking the helm, the team would sign Dominican infielder Ozzie Virgil Sr. Yet Virgil did not want the distinction of being the first Black Tiger. He told Detroit News reporter Joe Falls: “I’m not Negro; I’m Dominican; I’m Spanish.” Virgil was replaced the next season by an aging Doby, light-hitting middle infielder Ossie Alvarez and pitcher Jim Proctor, who had one start.

In an Aug. 22, 2017, op-ed to the Detroit Free Press, Walter Briggs Sr.’s great-grandson Harvey Briggs spoke of his grandpa’s philanthropy to the Detroit Institute of Arts and the Detroit Symphony Orchestra and noted that he helped found the Detroit Zoo. He did not, however, give gramps a pass that he was “a product of his time” or “no worse than many of his peers in the industry.” Instead, Harvey wanted to acknowledge the truth that, “He (Walter) was a racist.”

Inroads to integrate the Red Sox included the openly prejudiced manager Mike “Pinky” Higgins, who is quoted in Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist David Halberstam’s “The Summer of ’49” as saying, “There will never be any (N-word) on this team as long as I have anything to say about it.” Midway through the 1959 season, Higgins was replaced by Billy Jurges, upon which the Red Sox employed their first Negro, Elijah “Pumpsie” Green. Seven days later, pitcher Earl “No-hit” Wilson became Green’s roommate.

The unofficial quota system was expressed by Green in Danny Peary’s book “We Played The Game”: “Earl Wilson and I were roommates each time he was brought up to the majors. Naturally, in those days, if a team had three Blacks and two were roommates, the third one could be sent back to the minors. It was two by two.”

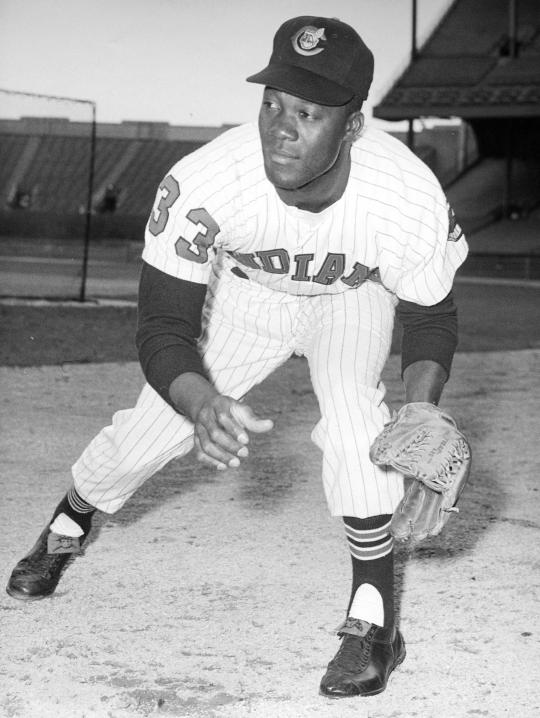

In Doby’s book “Pride Against Prejudice,” he mentions arriving in Cleveland on July 4 and having the newly hired African-American assistant public relations director, Louis Jones, assigned to be his roomie. Satchel Paige became his bunkmate the next season.

The percentage of minority players listed in the chart on this page (defined as African American or Latino) is based on outward appearances. As race is principally a social construct, the audience from this time eriod often organized Black and Brown players into one minority group. Latinos before 1947 and since the Plessy v. Ferguson decision, like Armando Marsans, Mike Almeida, Mike González, Jack Calvo, Adolfo Luque, Pete Aragón, José Acosta, Ricardo Torres, Pedro Dibut, Ramón Herrera, Óscar Estrada, Tomás de la Cruz and Chico Hernández, were socially whitewashed by owners to gain admittance. Ironically, these Brown stars also played on Black teams.

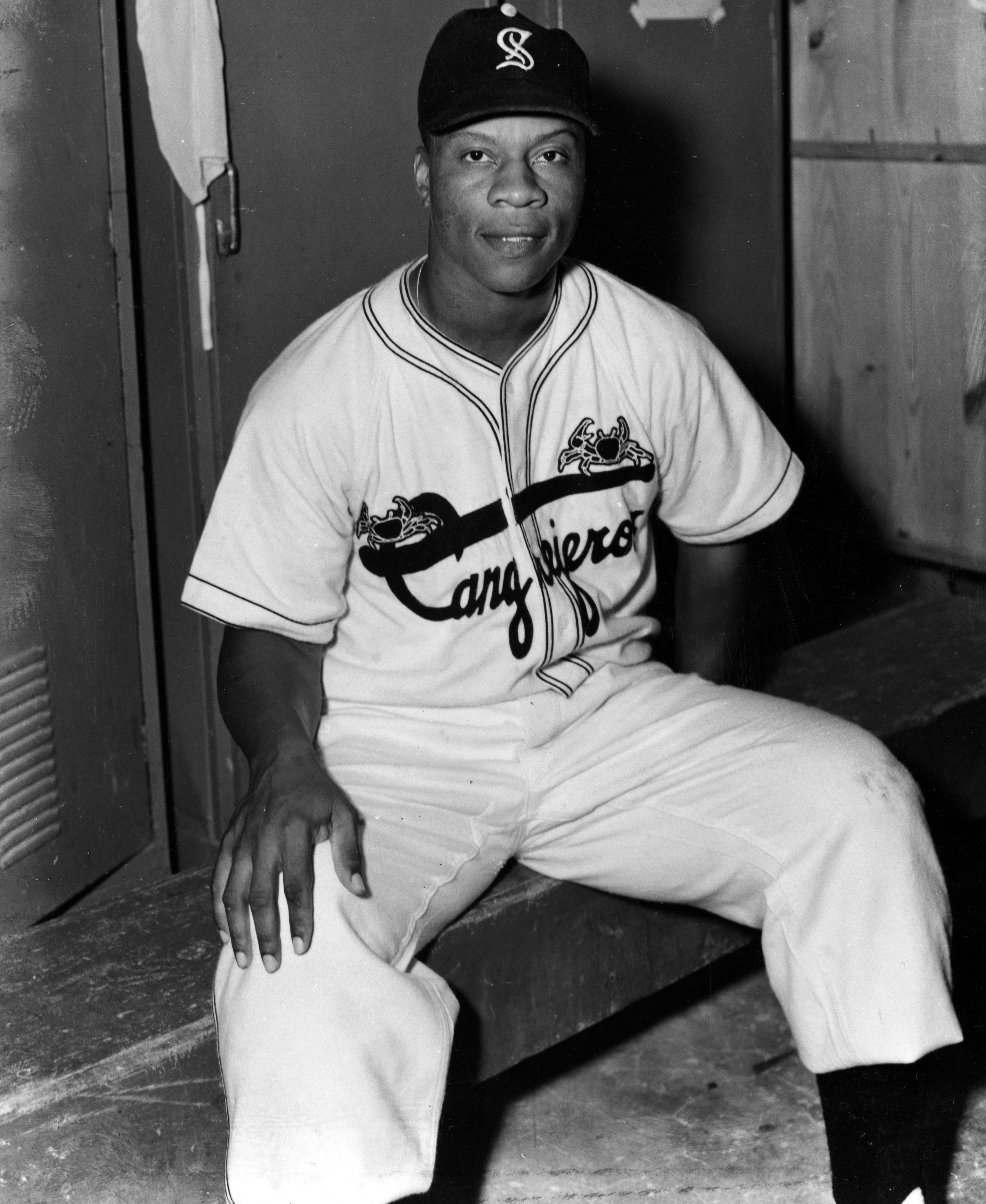

The first dark-skinned Latino in the AL or NL was Minnie Miñoso, who joined the defending champion Cleveland Indians in 1949. There he met teammates Paige, Doby and his roommate from the Homestead Grays, Luke Easter.

The 1960 Census reported that Black Americans comprised 11% of the U.S. population. That same year, with all deliberate speed, the Kansas City Athletics became the last major league team to employ an all-white roster for an entire season. They finished in last place, 39 games behind the Yankees.

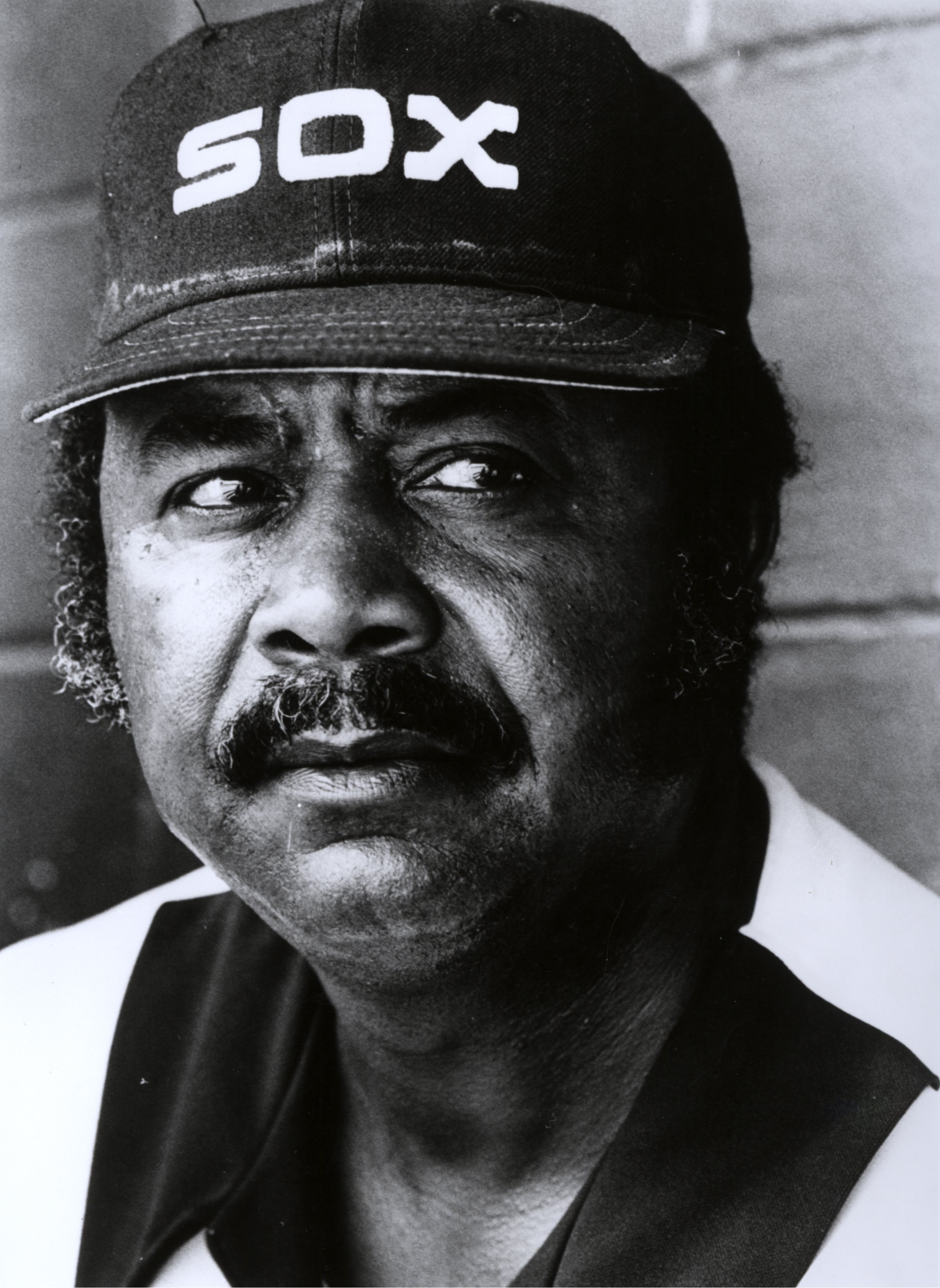

We don’t know each team’s policy regarding teammates rooming together during the early days of reintegration. However, in 1958, two rookie pitchers for the Cleveland Indians, Gary Bell from San Antonio, Texas, and Jim “Mudcat” Grant from Lacoochee, Fla., may have been the first white & Black roommates.

According to Grant’s book “The Black Aces,” “If there were three Blacks on the team, you roomed two and one had a single room by himself. So, we decided to break up the crap. We got a room (together). They didn’t hassle us too much, but they didn’t pay for the room. We had to pay.”

With segregated sanctions in place, it was common practice for teams traveling by bus to stop at restaurants that did not serve “Negroes,” forcing white players to bring meals back to the bus for their Black teammates. And once they arrived at the designated hotel, Black players were often denied occupancy. In turn, they roomed at private residences or Black-owned hotels, or had an occasional sleepover at a Black-owned funeral parlor.

With Jim Crow behind the wheel at the pedestrian speed of a school bus, the long and winding road to educate and integrate the original 16 teams, over 13 seasons, validates a horrendous testament about injustice on the field toward diversity and equality.

Today’s owners, albeit mostly a racially homogeneous group, welcome players of all colors in their efforts to capture the crown. May that progress continue. Batter Up!

Larry Lester is a curatorial consultant for the Hall of Fame’s ongoing Black Baseball Initiative.

Related Stories

Doby blazed trails on, off field

Banks transitioned seamlessly from Negro League to Cubs

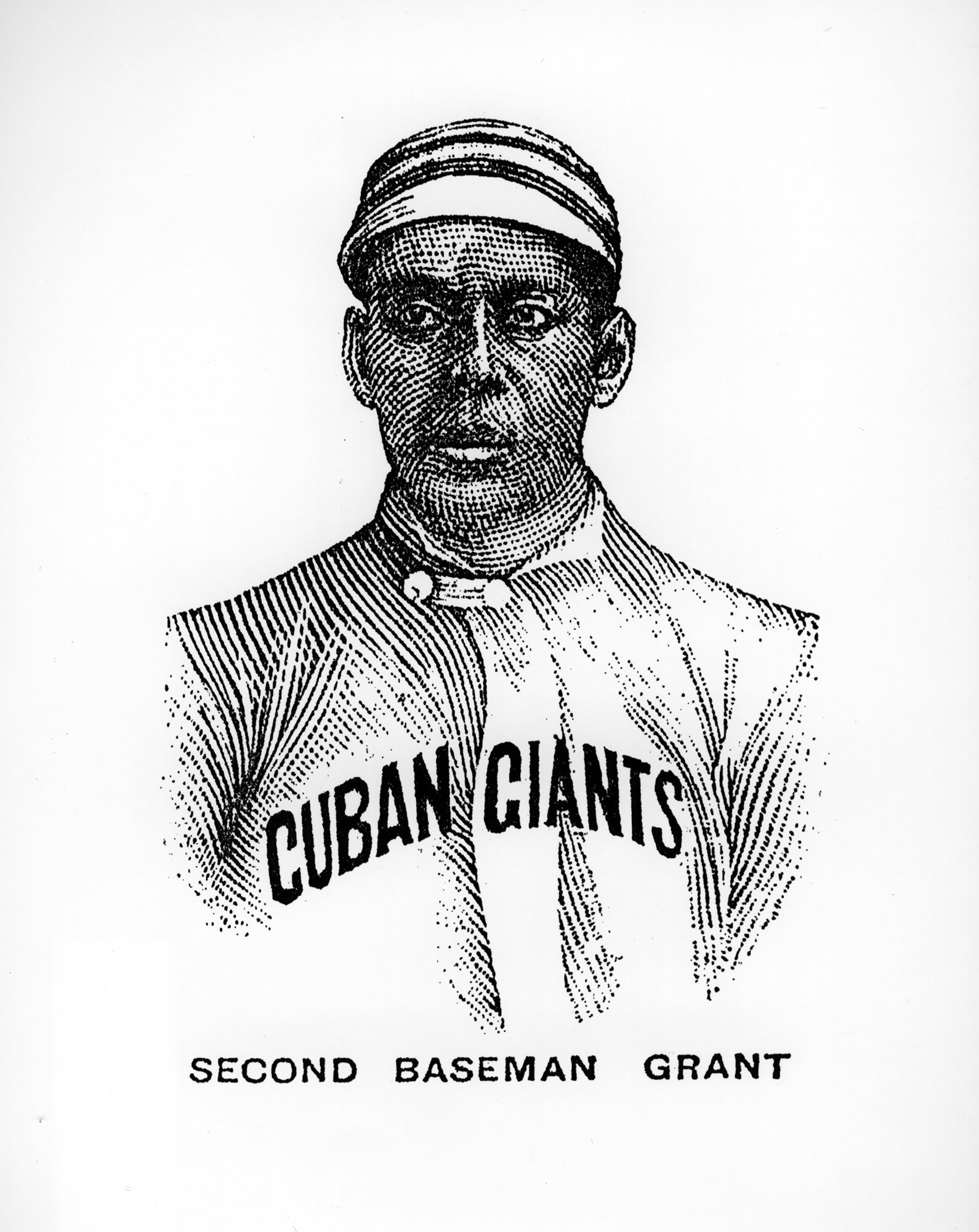

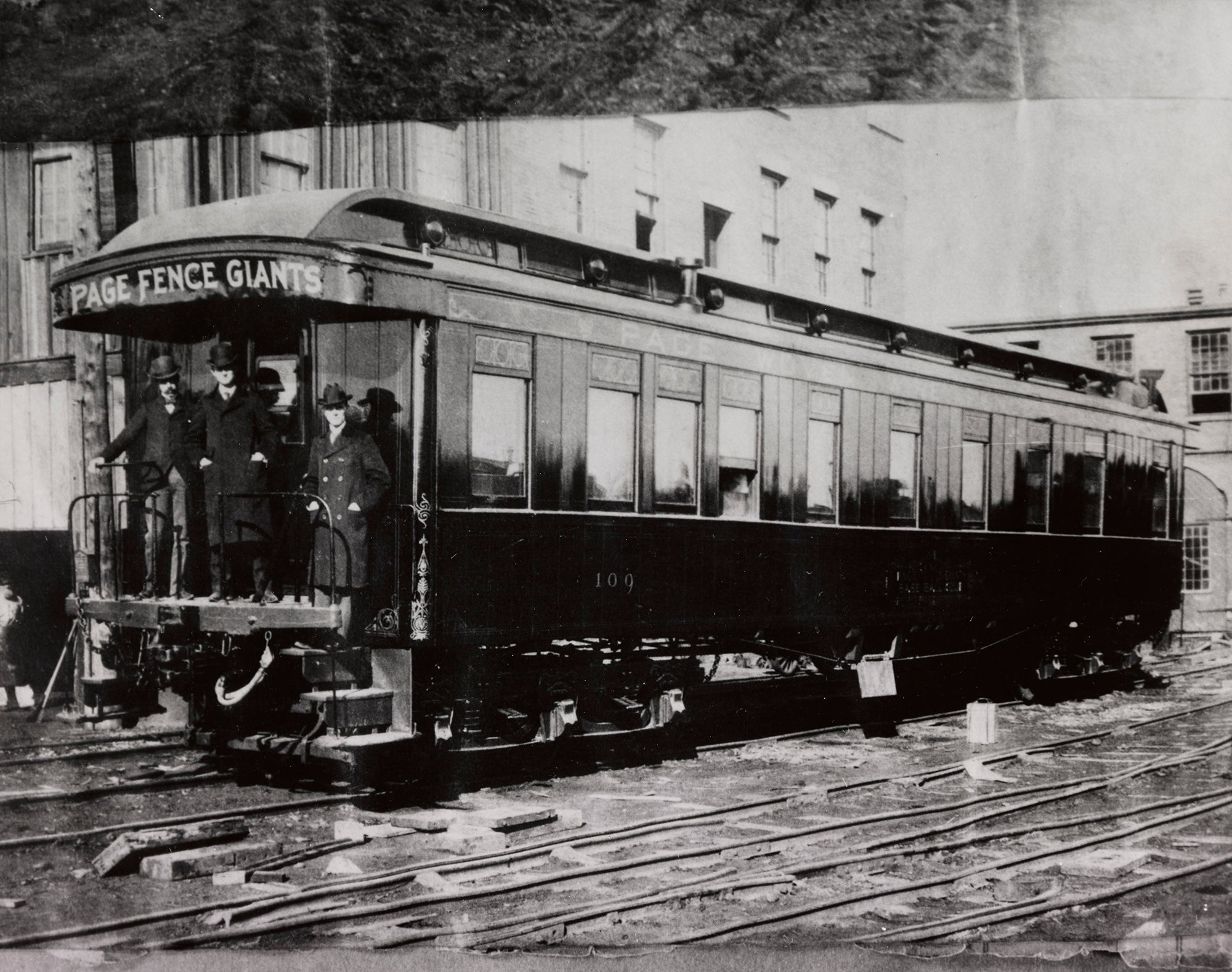

Pre-Negro Leagues stars laid the foundation for integration

Bud Fowler’s life blazed a trail from Cooperstown

Brown’s lone big league homer made history

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Mudcat Grant

A Look at a Legend

Frank Robinson made history in AL and NL

Jackie Robinson, circa 1946

Blockbuster trade brings Maranville to Pittsburgh

Museum Partners with Artist Bill Purdom for 75th Anniversary Artwork

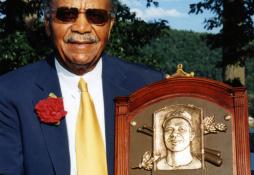

Twenty-five years ago, big league pioneer Larry Doby received his Hall of Fame plaque

01.01.2023

Griffey Jr., Piazza elected to Hall of Fame

01.01.2023

With deliberate speed, the 1950s saw the reintegration of the white major leagues

01.01.2023