- Home

- Our Stories

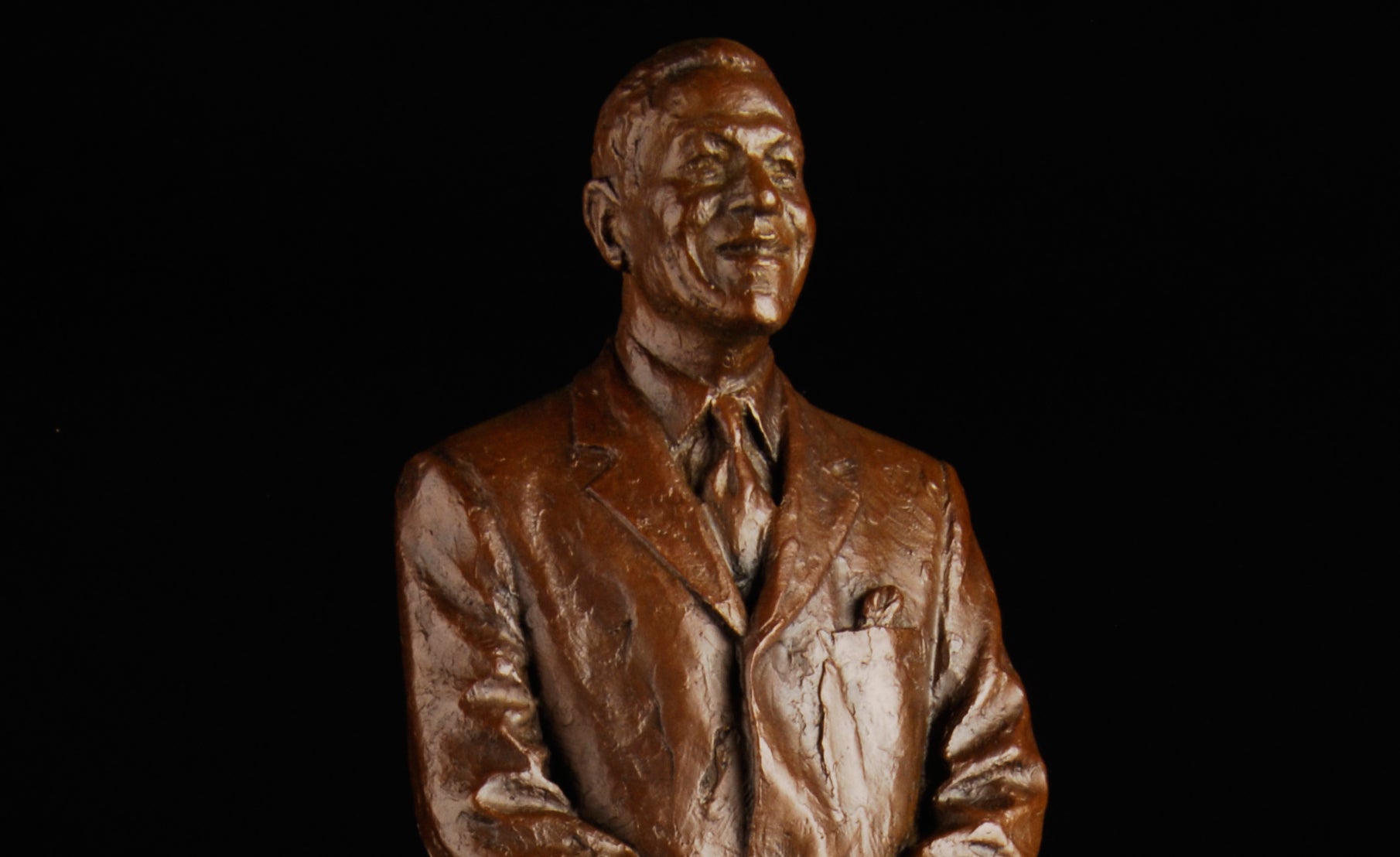

- 2016 Ford C. Frick Award Winner Graham McNamee

2016 Ford C. Frick Award Winner Graham McNamee

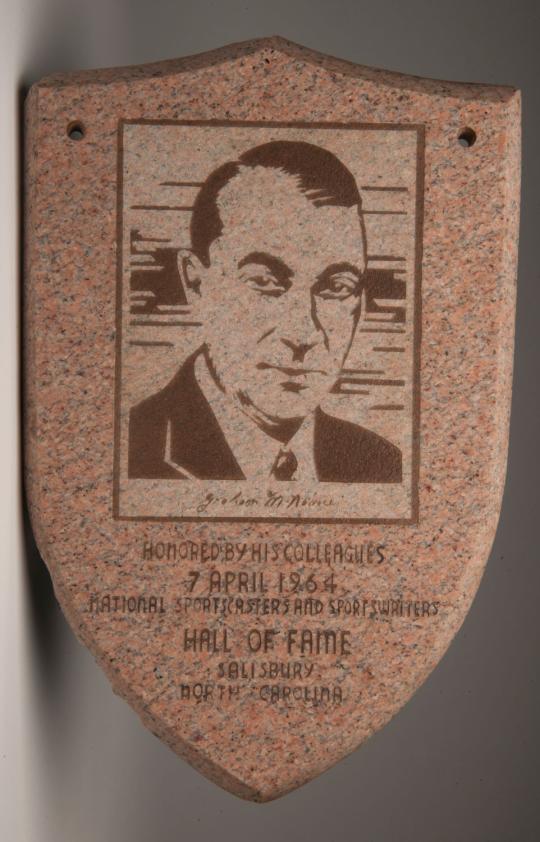

Graham McNamee, one of broadcasting’s first and brightest stars as a beloved voice to millions of listeners in the first half of the 20th century, was named the 2016 Ford C. Frick Award recipient.

It would have been almost impossible to miss McNamee’s voice if you owned a radio from the mid-1920s to the early 1940s. Not only was he was quite possibly the first celebrity sportscaster, but he was also a pioneering broadcaster, renowned as the most recognized personality during radio’s formative years.

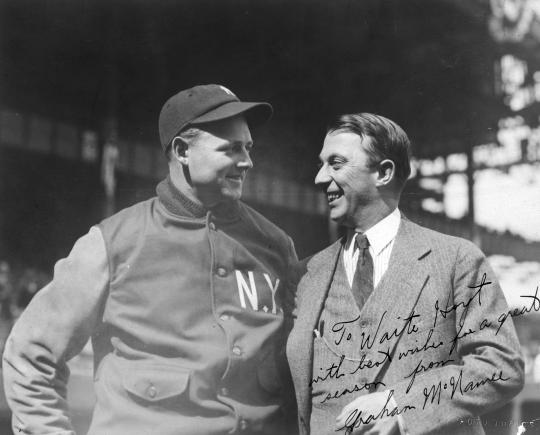

McNamee was a concert baritone when in 1923 he wandered into the WEAF radio studio in New York City looking for a job. Hired as an announcer at a station that would soon become home to the National Broadcasting Company, McNamee quickly became radio’s best all-around announcer. Soon, no football game, World Series, horse race, tennis match, inauguration, or other major event was complete without him.

His first sports assignment was the Harry Greb-Johnny Wilson middleweight championship at the Polo Grounds on Aug. 31, 1923. A few weeks later he broadcast the 1923 World Series between the Yankees and Giants. Over the next two decades he would call 12 World Series as well as 10 other sports. As a result of McNamee’s coverage of the 1925 World Series, WEAF received nearly 50,000 letters of appreciation.

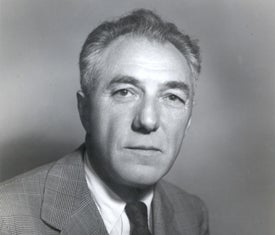

According to Red Barber, a longtime broadcaster for the Reds, Dodgers and Yankees, as well as the 1978 Frick Award winner, McNamee was the greatest sports announcer we ever had, adding “How he did what he did when he did…suddenly…completely unprepared…is to me a miracle.”

Regarded as the pioneer of sports announcers, McNamee set many broadcasting standards during his tenure. It wasn’t long after he began his radio announcing career that statisticians computed that the voice of McNamee had been heard for more hours by more human ears than any other voice in history.

Listeners to McNamee’s baseball broadcasts not only enjoyed his vivid description of the action on the field but also what was happening off it. In fact, McNamee once estimated that he used more than 10 times the number of words in an unabridged dictionary.

In his 1926 book “You’re on the Air,” McNamee described his baseball broadcasting style: “You must make each of your listeners, though miles from the spot, feel that he or she, too, is there with you in that press stand, watching the movements of the game, the color, and flags; the pop bottles thrown in the air…Gloria Swanson arriving in her new ermine coat; McGraw in his dugout, apparently motionless, but giving signals all the time.”

Jim Murray, 1987 winner of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America’s J.G. Taylor Spink Award, penned in 1978 that McNamee “was a great announcer because he never let the action on the field get in the way of his imagination. He called the game as it should be. If he forgot the score, he described the sunset. Ring Lardner said sitting next to McNamee was like having a doubleheader – the game you were watching, and the game you were hearing.”

Among the three sports events that McNamee broadcast that he considered most memorable was the fabled long count of the Jack Dempsey-Gene Tunney heavyweight fight in 1927, the comeback of Philadelphia Athletics pitcher Howard Ehmke in the 1929 World Series and the Babe Ruth “called shot” home run in the 1932 World Series.

Heywood Broun, the winner of the 1970 Spink Award, once wrote: “A thing may be a marvelous invention and still as dull as ditchwater. It will be that unless it allows the play of personality. Graham McNamee has been able to take a new medium of expression and through it transmit himself – to give out vividly a sense of movement and of feeling. Of such is the kingdom of art.”

A contemporary in the field, Phillips Carlin, described McNamee’s voice as the most vibrant and vital in radio, adding, “For nearly 20 years it thrilled those who heard it. Things, places and people became alive in the homes of America when he spoke.”

When McNamee passed away at the age of 53 in 1942, The New York Times wrote, “He was voluble in extemporaneous description and narration of events that took place before his eyes while a live microphone was before him and he had developed a technique for portraying accurately and interestingly, in fluent language, the sights at fast-moving sports contests, exciting political gatherings and many other varied assignments.”

In his eulogy for McNamee, Dr. Franklin Dunham said, “Thousands of little children now grown up will remember his ability, as we of broadcasting do, to make the simple thing vivid and real.”

“Good evening, ladies and gentlemen of the radio audience,” was a familiar opening refrain from McNamee.

Although his devoted audience would not need the identification, the young baritone who would become a trailblazing sports broadcaster in radio’s infancy would sign off his broadcasts with, “This is Graham McNamee speaking, Goodnight, all.”