- Home

- Our Stories

- Baseball nicknames provide gateway into America’s Pastime

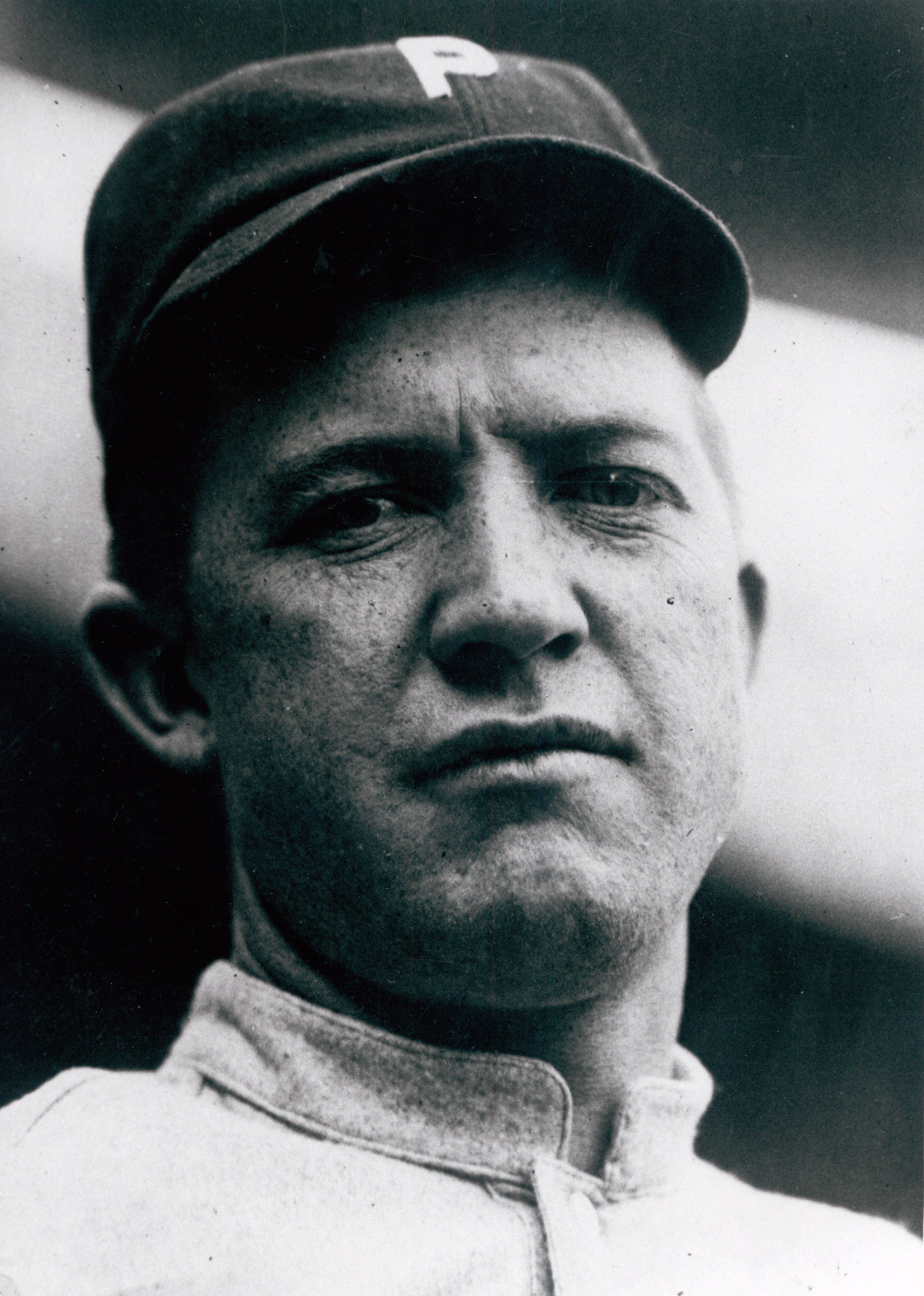

Baseball nicknames provide gateway into America’s Pastime

Alma Nelson Dean had high hopes for her fourth-born son from the moment he came into the world. Working as a sharecropper with her husband Monroe in Lucas, Ark., Dean had the foresight to know that somehow, someway, her boy would make a name for himself.

With that in mind, she declared him “Jay” – after Wall Street Financier Jay Gould – “Hanna” – after political figure Mark Hanna – “Dean.”

But it just so happened that the name she chose wouldn’t be the name he made famous throughout baseball.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

“Dean’s parents gave him the name of Jay, but his antics and eccentricities and whimsicalities earned for him the nickname of “Dizzy,” proclaimed the Boston Globe in 1932. “Speaking of his name, Dean himself says: ‘I may be dizzy off the field, but I am not dizzy when I am out there pitching a game.’”

Loquacious and eccentric – with a fastball that made batters spin – “Dizzy” fit Jay Hanna like a glove. There were countless theories on where the nickname originated from. But an interview between Vince Staten and Bob Brought in Ol’ Diz: A Biography of Dizzy Dean seemed to unearth the truth, once and for all.

“My father, Sergeant James Brought, pointed out to Private Dean that to accomplish the art of control you must practice and practice. One morning as Dad entered the Twelfth Field Artillery mess hall, he heard one heck of a noise coming from the basement,” Brought said. “He found Private Dean throwing potatoes at a trash can lid which was hung from the ceiling. Dad stopped the private and asked just what he was doing at 5:30 in the morning. Private Dean only smiled and said, ‘You said practice, Sergeant Brought, so I am.’ Dad’s only answer was, ‘Why you dizzy…, but not with potatoes.’ The incident was told throughout the Twelfth Field Artillery that day, and so the name “Dizzy” stuck.”

You read that first part right: Private Dean. Dizzy enlisted in the Army at age 16 – pretending to be two years older – and was stationed at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas.

“I played my first formal baseball game when the Third Wagon Company met the Twelfth Field Artillery,” Dizzy told The Saturday Evening Post. “Top Sergeant Johnny Brought, of the Twelfth, liked the way I done in the game. He said if I’d transfer to the Twelfth I could play ball more and shovel manure less.”

And so, it was in a culture of order and discipline that one of baseball’s zaniest characters was created.

Rumors of Deans’ prowess on the mound spread like wildfire, and he quickly found himself making a start against the Chicago White Sox in an exhibition game in San Antonio. After Dean’s dominant performance, Lloyd Gregory, a Houston-based writer for the Sporting News, wrote: “Two of the rookies showing exceptional promise are: Dizzy Dean from San Antonio, and Roger Traweek from Mexia, both right-handers. These young twirlers lack polish, but each has a lot of natural ability and a season in Class D baseball would work wonders for them.”

The moniker stuck with him until the end, and even made it onto his plaque in Cooperstown, joining some “Leftys,” some “Mickeys” and exactly one “Whitey.” But it seems that with every passing decade, nicknames become less and less common. According to James Skipper in Baseball Nicknames: A Dictionary of Origins and Meanings, the game saw its highest frequency of nicknames from 1910-1919 (502), followed a slight decline from 1920-1929 (452) to another in 1930-1939 (379). By the 1950s, only 164 nicknames were recorded in the Baseball Encyclopedia – just about a 70 percent drop in 40 years.

“Baseball grew up in the folk hero era,” writes Skipper. “Before World War II, most major league performers came from lower class origins in rural areas of large city ghettos. Their level of formal education was low or in some cases nonexistent. Legends and myths abounded concerning their abilities and activities. The appeal of the national pastime has always been foremost to the working classes. Baseball players exemplified how ‘folk people’ could receive recognition, financial success and general social mobility. Spectators could achieve wish fulfillment through identification with the players.”

Moving away from the days when baseball fans got their information from newspapers and radio broadcasts, as the game advanced technologically and economically, it shed a bit of its folklore traditions.

“TV plays a big part of it,” broadcaster Chris Berman said in an interview with ESPN. “When classic nicknames were made up in those days all you had was radio and the newspapers – you never actually saw these people. Writers were more colorful to create a picture for the fan. But now there’s no need to write like that. When you see their pictures on TV, you don’t need that anymore. I think TV killed off some of the romance of the game, though it opened it up to a wider audience.”

And to accompany the changes in baseball, the media landscape shifted as well.

“I think part of it is the fault of journalists,” said Thomas Heitz, Baseball Hall of Fame librarian from 1985-95. “Newspaper editors, AP style guidelines and the like discourage the use of nicknames in print. There are still quite a few nicknames in the clubhouse, but they never see print these days. I just think styles have changed.”

Regardless of the reasons why nicknames are largely a thing of the past, the tradition will make a renaissance of sorts for MLB’s “Player’s Weekend.” While baseball accords its athletes full creative freedom on their jerseys, it simultaneously allows fans to see baseball’s biggest names in a new light, as if to reimagine them in a different era. Only time will tell whether the names will stick or not – but a few more “Reds” and “Babes” never hurt anyone.

Alex Coffey was the communications specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum