- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1969 Topps Hawk Harrelson

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Hawk Harrelson

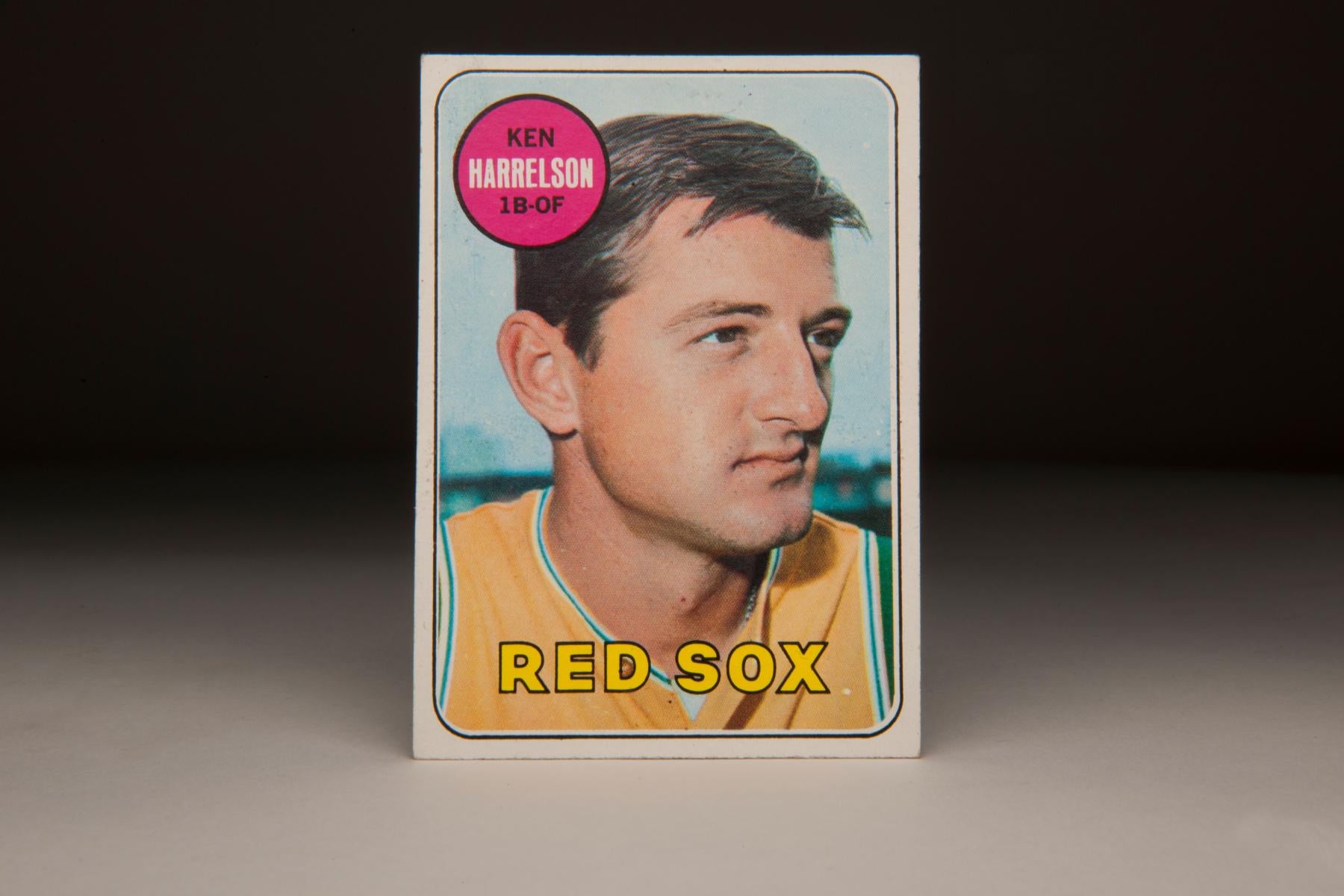

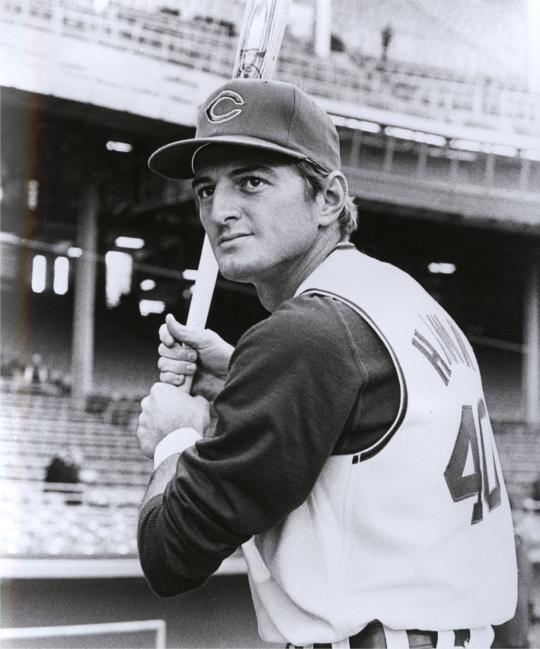

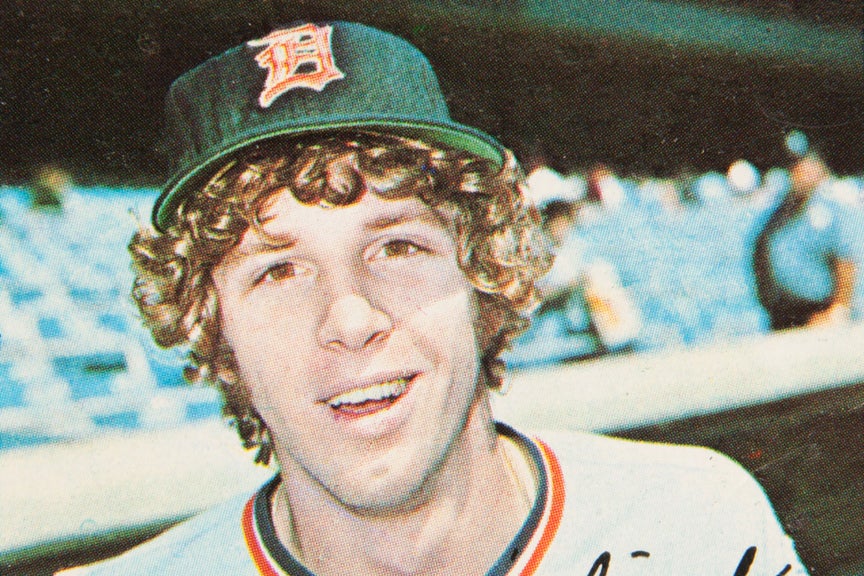

As his 1969 Topps card can attest, Ken Harrelson had one of the more distinctive appearances among ballplayers in the 1960s. He had a large nose, which is in full view on the card and was responsible for his nickname “The Hawk.” Harrelson was also one of the better looking players of his era, with boyishly defined features, a solid jawline, a cleft chin (reminiscent of Kirk Douglas), and relatively well-coiffed hair. Those looks, along with his status as a player of some talent, made him something of a baseball “rock star” back in the day.

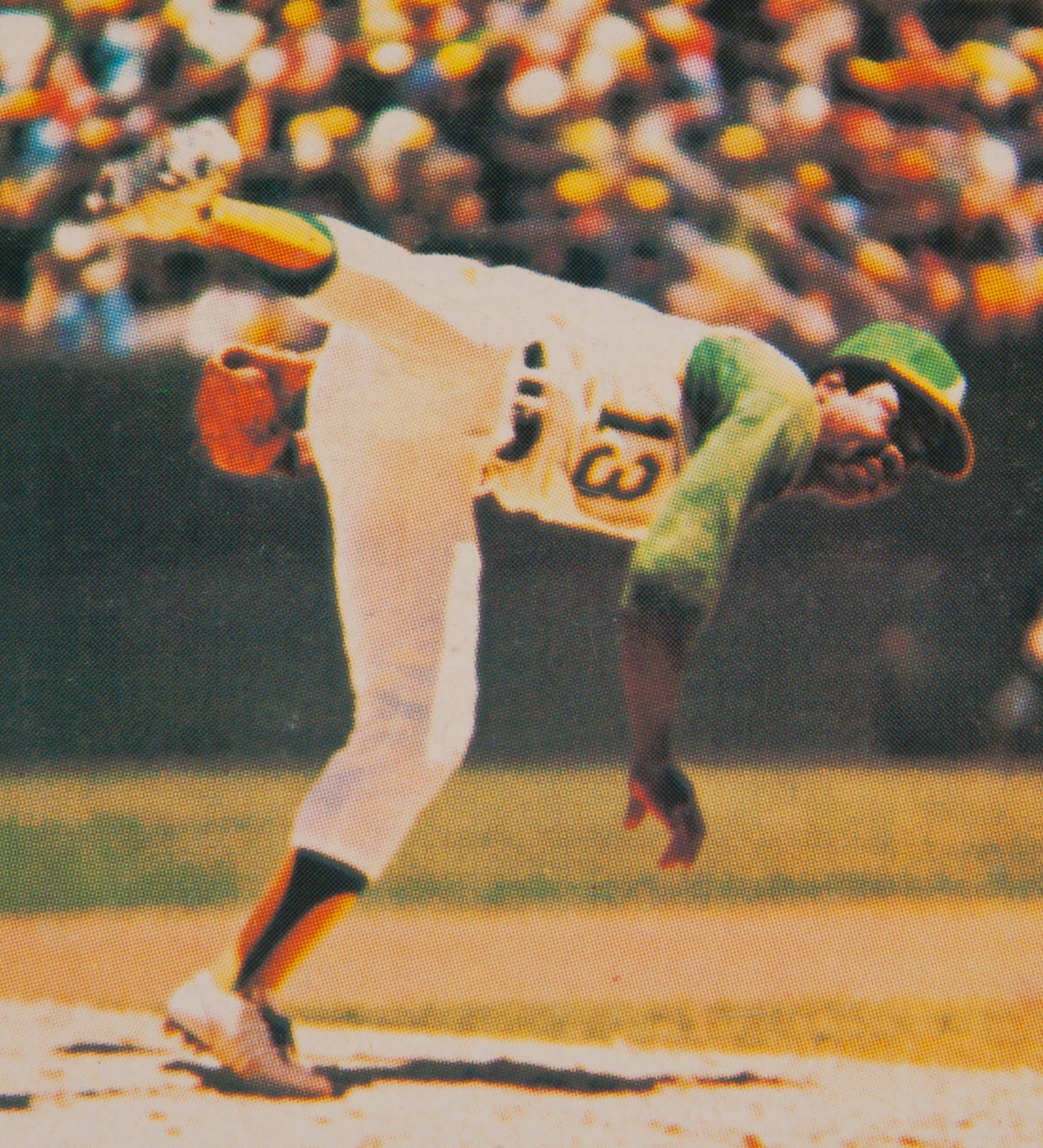

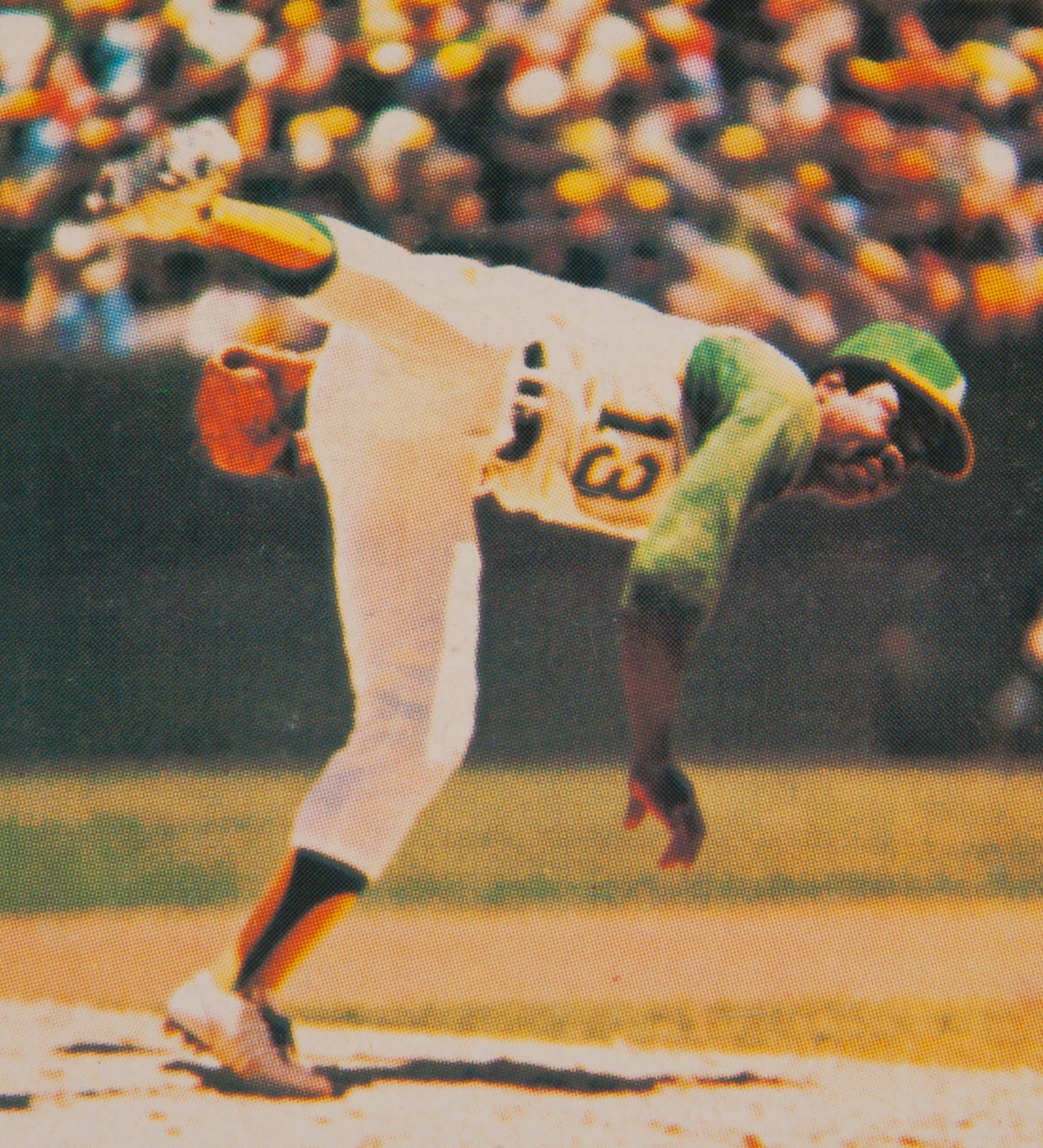

Harrelson’s card also provides a bit of confusion. Like most of the 1969 cards, it features an outdated photograph, motivated by the Players’ Association refusal to sit for new photographs with Topps. We see that The Hawk is clearly wearing the green and gold colors of the A’s, who were still in Kansas City when this photo was snapped (possibly in 1966 or ’67), but had moved to Oakland by the start of the 1968 season. In contrast to the colors of the A’s, the bottom of the card designates Harrelson as a member of the Boston Red Sox. As it turned out, Harrelson would play in a grand total of only 10 games for the Sox that spring; only a few weeks after Opening Day, he was sent packing to the outpost of Cleveland, Ohio, where he would play rather reluctantly for the Indians.

The start of Harrelson’s professional career was also eventful. He spent the better part of five seasons in the minor leagues, playing everywhere from Binghamton to Portland, before earning a promotion to Kansas City in 1963. When he finally made his big league debut for the A’s, he batted only .230 with six home runs, weak numbers for a first baseman/outfielder.

As a rookie, Harrelson came up with an intriguing innovation, but completely by accident. After playing two rounds of golf with some teammates one afternoon, Harrelson reported to the ballpark with blisters on both hands - and in no condition to play that night. When he arrived in the clubhouse, he discovered that the New York Yankees had switched starting pitchers, opting for Whitey Ford over the expected right-hander. With a left-hander now pitching, Harrelson realized that he would have to start the game. With his hands full of blisters, Harrelson decided to retrieve his golf glove from the clubhouse and wear it, drawing laughs from several players on the Yankees. “That’s when Whitey hung me the curve ball and I hit it out,” Harrelson said during a visit to Cooperstown a few years ago. “Well, the next day, the Yankees come out of the clubhouse - and they all had red golf gloves on. [Mickey] Mantle had sent the clubhouse guy to get a couple dozen golf gloves.”

Mocking from the Yankees aside, Harrelson felt that the golf glove improved his grip on the bat. His performance that night supported his theory. Not only did some of the Athletics and Yankees follow suit by wearing gloves of their own, but so did other players around the league. In becoming the first major leaguer to regularly wear batting gloves, Harrelson became a trendsetter. By the time Harrelson retired in the early 1970s, batting gloves had gained mainstream acceptance.

Harrelson’s batting glove arrived in 1963, but he started the 1964 season back in Triple-A, where he didn’t hit particularly well. Still, the A’s called him up in July. He struggled, hitting only .194 and becoming a bench player by season’s end. Upset with his performance, Harrelson decided to report to winter ball for the first time. He played in the Venezuelan Winter League, where he proceeded to make a reputation for himself as an undefeated arm wrestler and a crack pool shooter. At one point, he brawled with an umpire, resulting in a 15-day suspension. The legend of The Hawk was beginning to grow around the game.

Perhaps the winter league experience helped Harrelson’s on-field performance, too. He finally achieved success with the A’s in 1965; he hit 23 home runs and drew 66 walks. He played well enough to give the A’s hope that he had solved their first base problem.

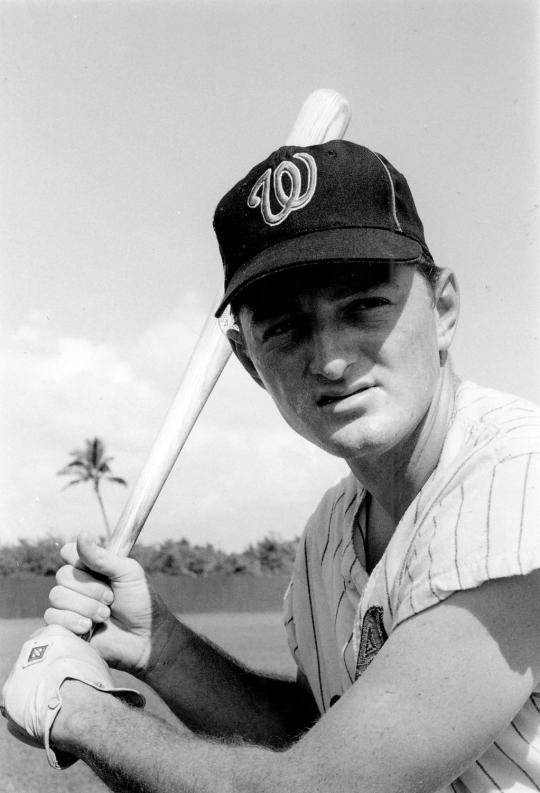

Off the field, Harrelson led an extravagant life. He loved to spend money, more than what we had. “I was making $12,000 [a year],” Harrelson said during his visit to Cooperstown, “and spending $30,000.” He would continue those free-spending ways for the rest of his playing days. After his impressive 1965 season, Harrelson found it difficult to sustain his newfound success. The first half of 1966 saw a major fallback. Harrelson not only hit poorly but he angered Kansas City owner Charlie Finley when he repeatedly asked for a raise. Finley lost patience with the demands of his young slugger and decided to cut him loose. On June 23, the A’s sent Harrelson to the Washington Senators for right-handed pitcher Jim Duckworth.

Harrelson fared no better with the Senators. In fact, he lasted less than a calendar year in Washington. On June 7, 1967, the Senators sent him packing - and sent him back to Kansas City, this time for cash only. The Hawk did well in his return to Kansas City, hitting .305 over 61 games. But circumstances having nothing to do with on-field performance short-circuited his second stint in Kansas City, while changing the path of his career drastically.

Given their similarly rebellious styles, it’s surprising that Finley and Harrelson could not have co-existed longer with the Athletics. After Finley fired manager Alvin Dark in the aftermath of an ugly on-flight incident involving some of the Kansas City players, Harrelson allegedly disparaged his employer with a seven-word indictment. “Charles Finley is a menace to baseball,” Harrelson was quoted as saying. Harrelson claimed that he never made that remark, though he was not Finley’s biggest fan. As Harrelson once mentioned during his visit to Cooperstown, Finley’s mascot mule “went first class; we went second.”

Finley demanded that Harrelson attend a press conference and issue a formal apology for his insulting remark about being “a menace.” Harrelson argued that he shouldn’t have to apologize for remarks that he never made. Ultimately, Finley responded to the alleged “menace” insult by doing to Harrelson what he did to Dark. He announced that he had “fired” his first baseman, choosing unusual terminology to indicate that he had given a player n his unconditional release.

Although it appeared to be a setback, Harrelson took advantage of the situation by making himself available to the highest bidder. Essentially able to work the market like a free agent, Harrelson worked the phones, soliciting offers from several teams that showed interest. After three days of wining and dining, Harrelson signed a $150,000 contract with the pennant-contending Red Sox.

The Red Sox badly needed a right-handed power hitter because of the loss of injured right fielder Tony Conigliaro. As Conigliaro’s replacement, Harrelson’s overall numbers were not impressive, but he did manage to drive in 14 runs in 23 games. He delivered several key hits for the Red Sox, who successfully staved off three other contenders in pursuit of their pennant.

Harrelson did not respond well to his first and only dose of postseason play. Coming to bat 13 times against the St. Louis Cardinals in the World Series, he delivered only one hit.

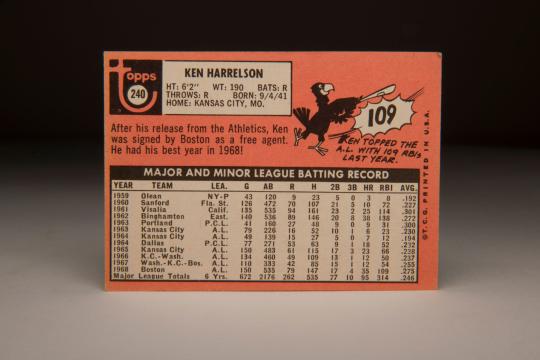

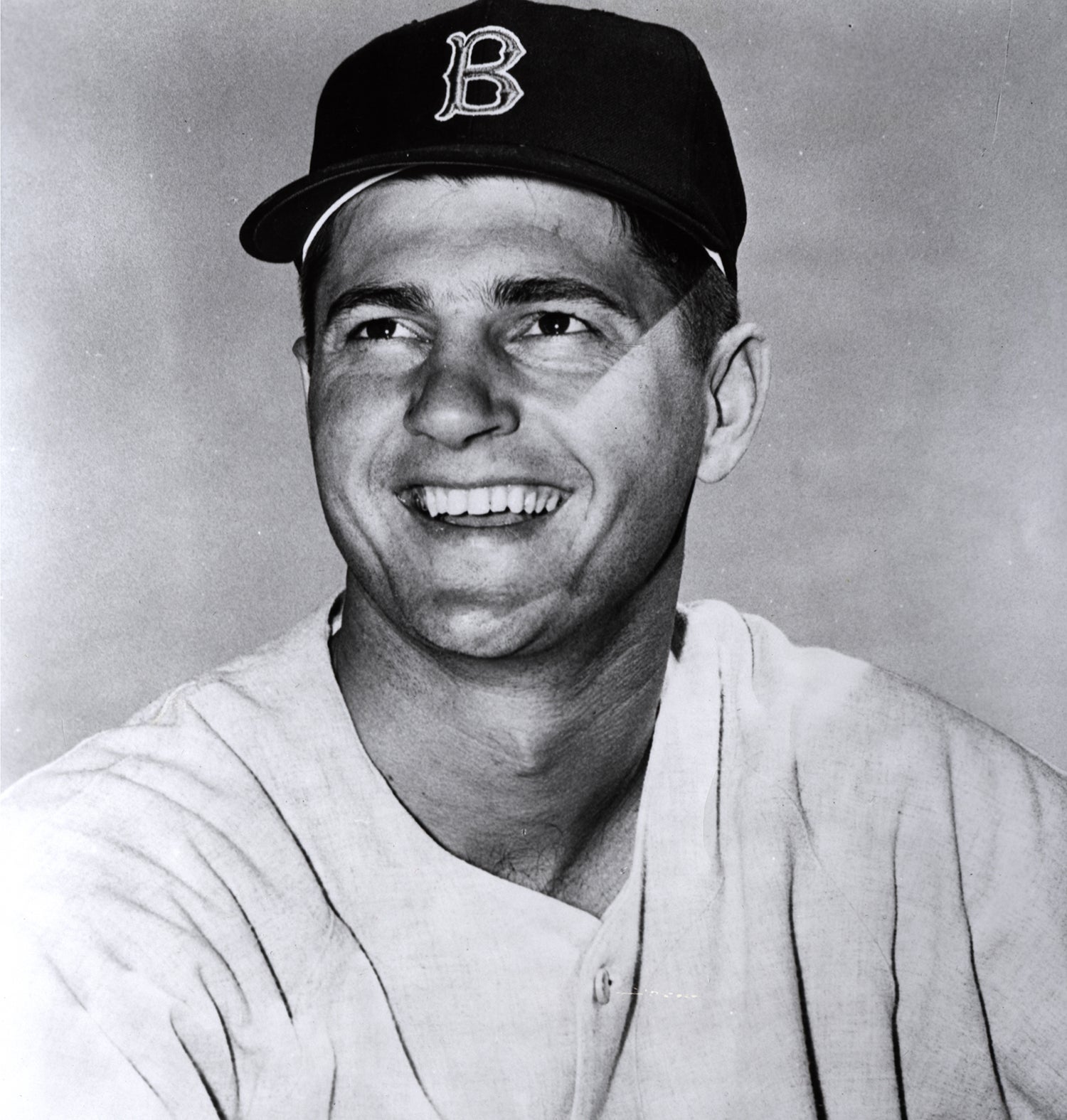

Despite a series of trade rumors that had Harrelson heading out of town to make room for young flychaser Joe Lahoud, the Hawk remained in Beantown. Seemingly unaffected by circumstances that made 1968 the Year of the Pitcher, Harrelson exploded into offensive stardom. Taking full advantage of the left field dimensions at Fenway Park, he belted a career-high 35 home runs, slugged .518, and led the American League with 109 RBIs. Harrelson’s performance earned him a third-place finish in the MVP race, but an even higher standing in the minds of a respected baseball publication. The Sporting News named him its American League Player of the Year.

Harrelson also made the cover of Sports Illustrated that season. He then sent a copy to his old employer, Mr. Finley, just to remind the owner of the mistake that he had made in firing The Hawk.

Harrelson became a national celebrity, a status that he embellished with his choices of elaborate clothing. Unlike most players who wore the traditional jacket-and-tie look on road trips, Harrelson adorned himself in the “mod” fashion preferred by young men in the late 1960s. He mixed and matched bright colors with loud stripes and check patterns. He wore Paisley-colored bell-bottom pants, sometimes matching purple trousers with white shoes (and no socks). He also sported love beads and large sunglasses.

In particular, he liked to wear Nehru jackets, which had become all the rage in 1968 fashion.

In retrospect, Harrelson attributes his fashion and grooming choices to the influence of his alter ego, which he refers to by his nickname. “‘The Hawk’ wants to wear the wild clothes, the long hair,” Harrelson explained, describing his other, separate persona. “‘The Hawk’ was an unusual guy.”

While many fans and members of the media referred to him as Hawk Harrelson, none of his Topps cards ever did. On every one of his card, including his 1969 offering, Topps listed him as “Ken.” Generally speaking, Topps preferred using standard names over nicknames during the 1960s and 70s. If there was a choice of names, Topps usually took the conservative route on the face of its cards.

The Hawk was anything but conservative, either in terms of personality or his off-field pursuits. Becoming larger than life in Boston, he quickly turned his instant celebrity into business opportunities. He opened up his own travel agency, an insurance company, and a restaurant where he sold submarine sandwiches. He also added a distinctive touch to his spending habits by purchasing a lavender dune buggy.

Harrelson appeared a perfect fit for the Red Sox and their rabid fan base. It would have been unthinkable to imagine Harrelson leaving the Sox the following season. But it happened.

Despite the designation of “Red Sox” on his 1969 Topps card, Harrelson lasted only 10 games with Boston that season. As well as Harrelson had played in 1968, the Red Sox now faced a quandary, with Conigliaro returning to play right field, Carl Yastrzemski in left field, and George Scott at first base.

On April 19, the Red Sox announced a blockbuster trade that relieved the logjam but shocked the Red Sox’ fan base. The deal packaged Harrelson with pitchers Juan Pizarro and Dick Ellsworth, all headed to the Cleveland Indians for catcher Joe Azcue and pitchers Sonny Siebert and Vicente Romo. Unhappy with the trade, several Red Sox fans picketed outside of Fenway Park.

Upon being traded from the Red Sox to the Indians in April of 1969, Harrelson made it clear that he wanted no part of Cleveland. “Where else in the [league] is the lake (Lake Erie) brown and the river (the Cuyahoga River) a fire hazard?” Harrelson asked rhetorically, endearing himself immediately to the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce.

Hoping to make the best of a less-than-ideal situation, Harrelson employed an interesting strategy shortly after the Red Sox traded him to Cleveland. Not wanting to play in Cleveland and give up his many business interests in the Boston area, Harrelson “retired” for 48 hours. He said he had no desire to leave Boston, claiming that he would prefer stepping aside completely rather than not play for the Red Sox.

At the time, most major league players did not have agents, instead relying on themselves to negotiate new contracts. Harrelson was one of the exceptions, having hired Bob Woolf, arguably the highest profile agent of the day. So Harrelson and Woolf met with Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, American League President Joe Cronin, Red Sox general manager Dick O’Connell, and Indians GM Gabe Paul in New York City.

The Red Sox declared that they would not take Harrelson back, leaving the slugger in limbo. The meeting seemed to sway Harrelson, who realized he would miss the game badly, but he wasn’t about to report to Cleveland without some kind of concession. He succeeded in using his brief “retirement” as leverage, finagling a new two-year contract from the Indians. It was not something that Ken Harrelson likely would have done, but it was exactly the kind of shrewd business move that Hawk Harrelson would have done - every time.

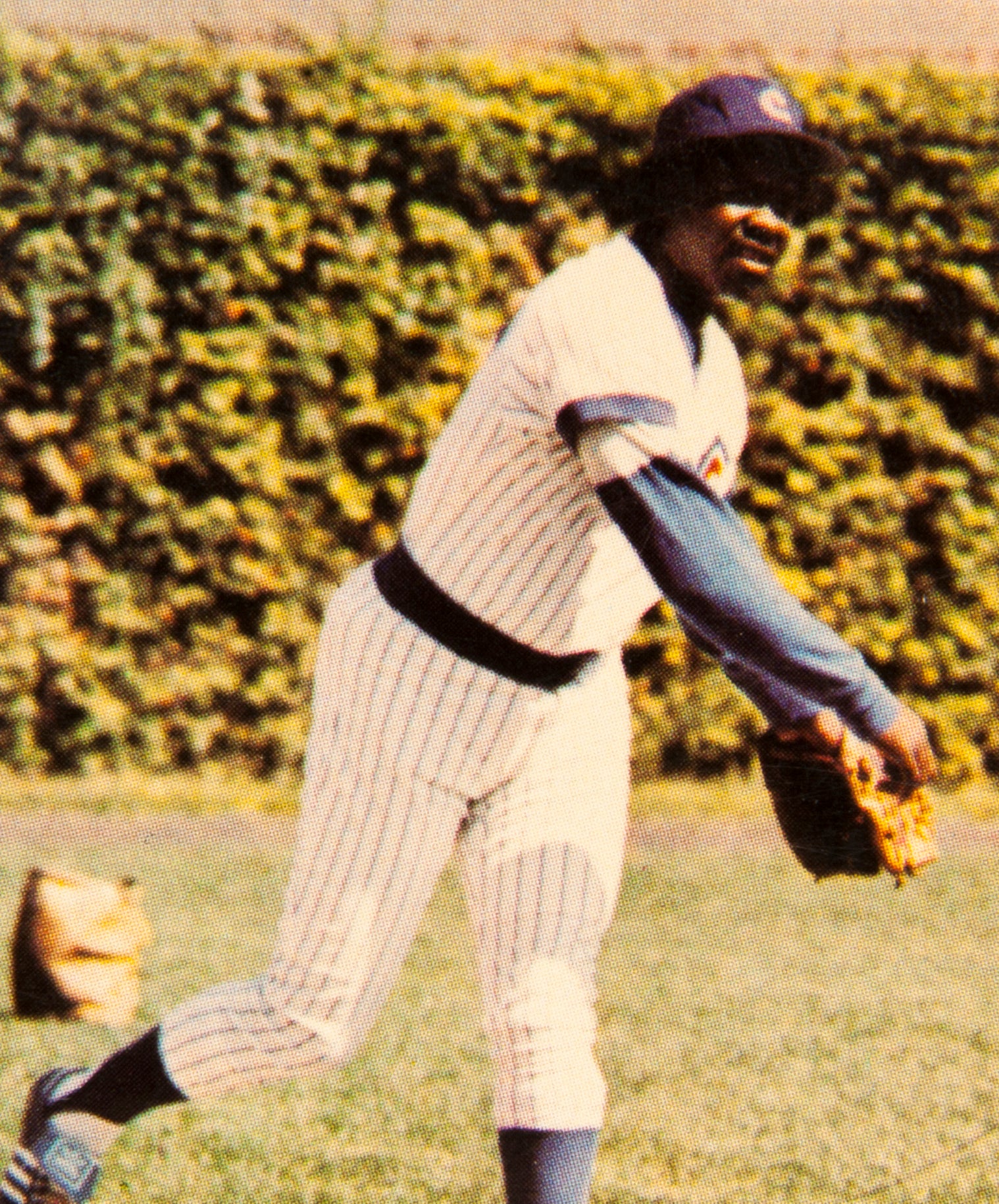

Upon reporting to the Indians that spring, the maverick first baseman created another stir, albeit a much smaller one, by having the letters “HAWK” stitched above his number in lieu of the traditional use of his surname. Harrelson thus continued a practice that his former owner (the inimitable Finley) had started with Kansas City.

Though he did not match his numbers from 1968 and batted only .221, in part because of a departure from Fenway Park, he still finished with impressive totals. He hit 30 home runs, drew a career-high 99 walks, and even added a dose of speed by surprisingly stealing 17 bases.

Off the field, Harrelson found Cleveland surprisingly abundant in business opportunities. He endorsed several local products and also found an author to co-write his autobiography. In retrospect, Harrelson said that he hated only cavernous Municipal Stadium, especially its long dimensions and its cold winds, not the city of Cleveland itself.

Then came the travails of 1970. Harrelson was hitting well during Spring Training, but while playing against the A’s, he slid into second base on a takeout play and came up yelling. He had broken his leg in two places, the injuries forcing him to miss most of the season. He played only 17 games that season, essentially losing his grip on the Indians’ first base job. Continuing to struggle with the leg in 1971, Harrelson played in only 52 games, struggled at the plate, and gave way to impressive rookie Chris Chambliss.

There was at least one light moment in 1971. Prior to a game at Municipal Stadium, Harrelson and Indians teammate Sudden Sam McDowell had some fun by filming their own version of Abbott and Costello’s famed “Who’s on First?” routine. Harrelson and McDowell delivered their lines as if they were professionally trained actors - almost flawlessly executing the lengthy skit with a sense of timing that would have made Bud Abbott and Lou Costello proud. At times, Hawk and Sudden Sam strayed from the original script, giving the performance a unique interpretation while also managing to make fun of their own on-field struggles in Cleveland. It was wonderful theater that was captured forever on film.

By the end of the ‘71 season, Harrelson had tired of the major league lifestyle and decided to make good on his repeated threats of retirement. Only 29 years old, Harrelson gave up his salary of $100,000 - all for the chance of being a fulltime player on the PGA golf tour.

Harrelson stayed with the PGA Tour for three and a half years, only to call it the “worst job in my life.” By his own admission, Harrelson did not have the right temperament for golf. “I’d start a round with 14 clubs,” said Harrelson, “and finish with two.”

In 1975, Harrelson returned to baseball as a broadcaster. Capitalizing on his outgoing personality and colorful charm, he auditioned for a position as a Red Sox broadcaster. Though he had no experience in the broadcast booth, Harrelson beat out over 700 applicants for the position.

Harrelson remained on the job for a few years, but his criticism of general manager Haywood Sullivan resulted in his 1982 firing. Harrelson then found work with the Chicago White Sox, where he joined Hall of Famer Don Drysdale on TV broadcasts. In 1986, he made the unusual transition from the broadcast booth to the front office, becoming the White Sox’ general manager. Unfortunately, that job stint did not go as well, as Harrelson made the mistake of firing a future Hall of Famer manager (Tony LaRussa) and a respected pitching coach (Dave Duncan), and trading away young talents (like Bobby Bonilla) in a series of bad deals. After only one season, Harrelson resigned under pressure.

His front office career over, Harrelson returned to broadcasting as a member of the New York Yankees’ crew before coming back to the White Sox in 1990, working games in Chicago until his retirement following the 2018 season. He was one of the game’s unabashed “homers,” loved by White Sox fans and often hated by fans of other teams. His creation of unusual nicknames, his distinctive home run call, and his heated rants against umpires also hallmarked his broadcasting style.

Harrelson won the Ford C. Frick Award in 2020, and all these years later, Harrelson looks quite a bit different these days. But he still has that distinctive aquiline nose, and a flair for colorful, offbeat behavior that never seems to wane.

From 1969 through the present day, Harrelson is still unquestionably The Hawk.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

More Card Corner

#CardCorner: 1981 Fleer Lynn McGlothen

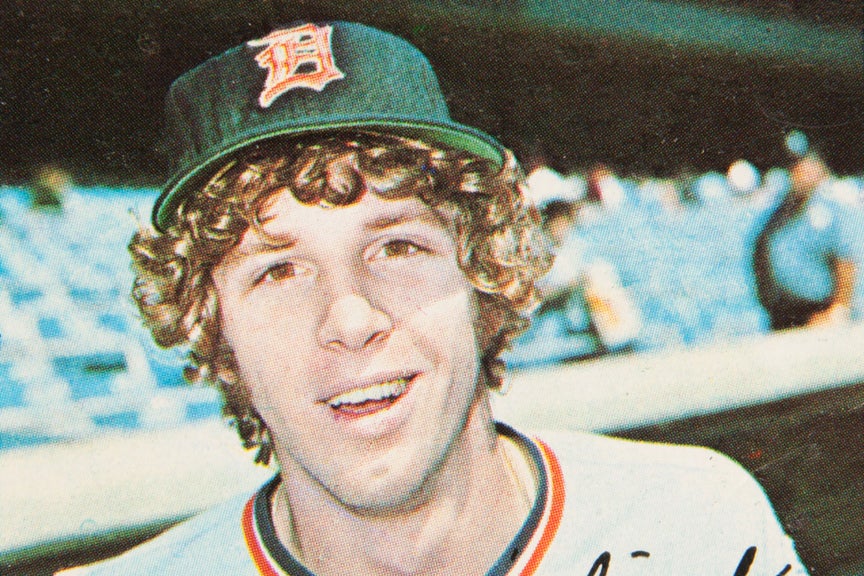

#CardCorner: 1977 Topps Mark Fidrych

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Blue Moon Odom

#CardCorner: 1981 Fleer Lynn McGlothen

#CardCorner: 1977 Topps Mark Fidrych