- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1978 Topps Rawly Eastwick

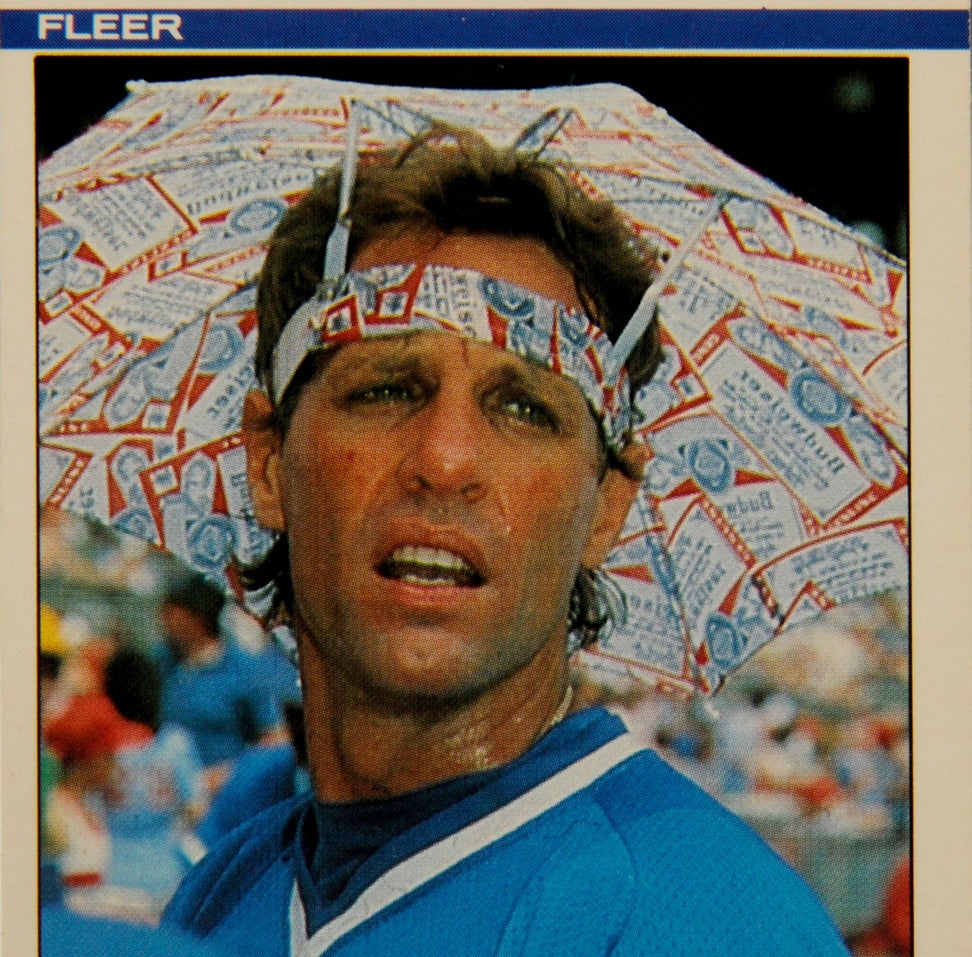

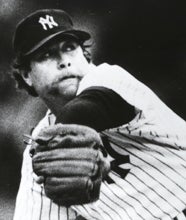

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Rawly Eastwick

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

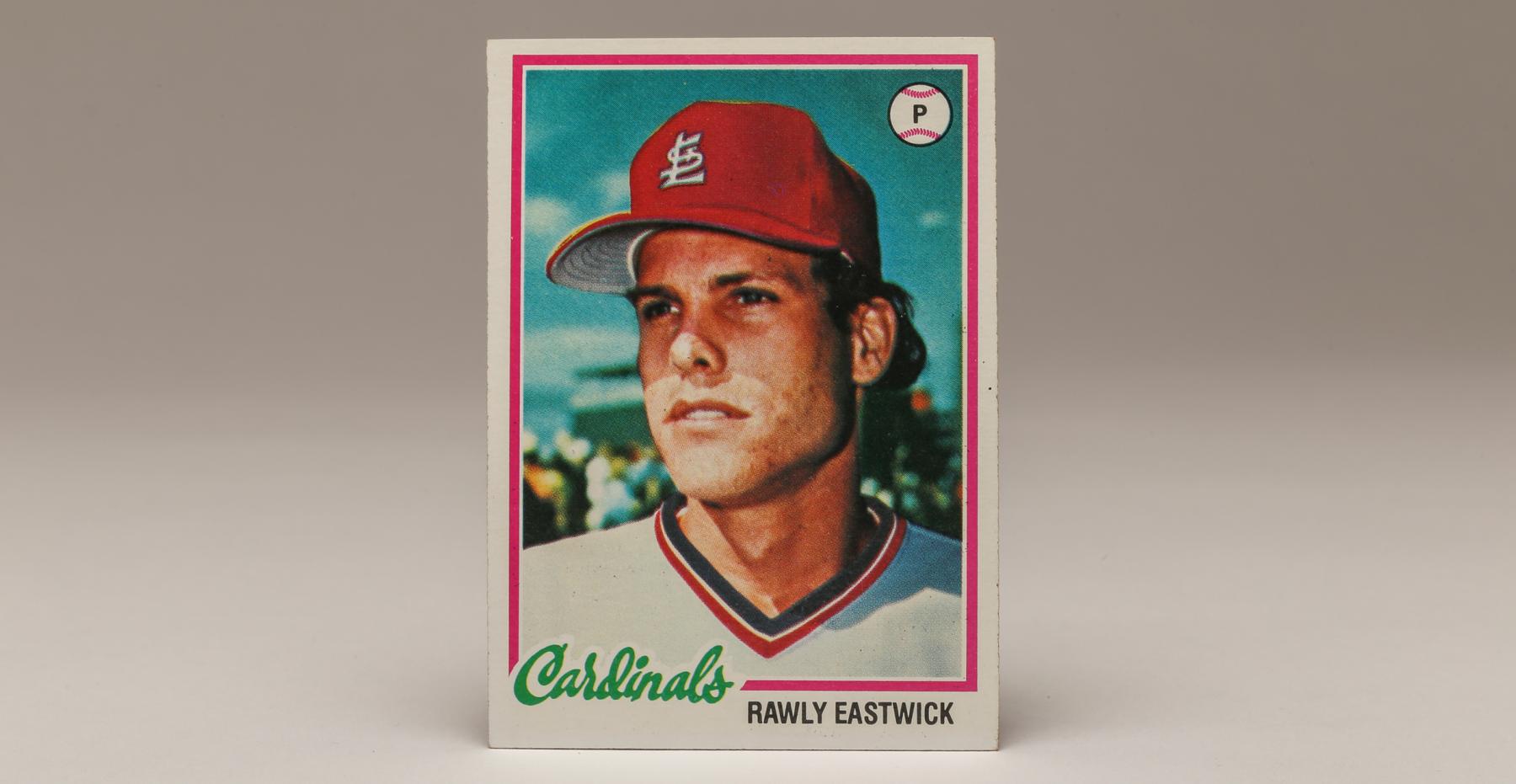

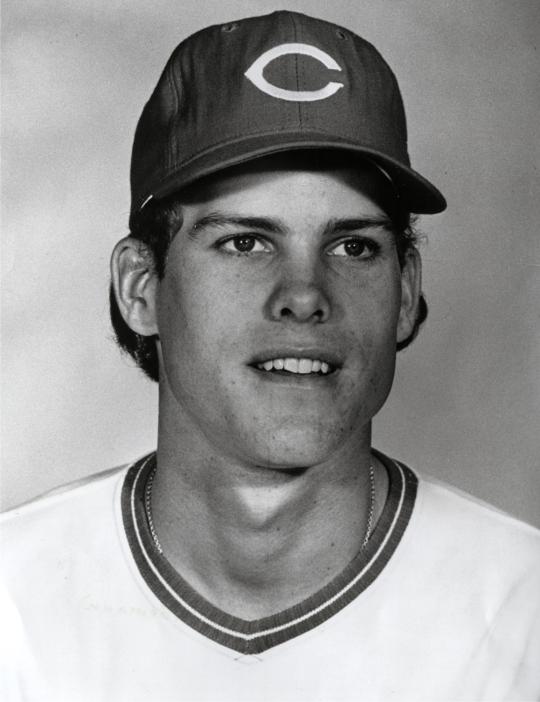

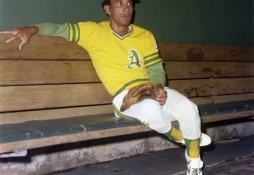

Of all the cards that Topps produced of Rawly Eastwick, none does a better job of capturing his baby-faced look than his 1978 card. Other than former Pittsburgh Pirates relief ace Kent Tekulve, I can’t think of anyone who looked less like a ballplayer than Eastwick. At six feet, three inches and 175 pounds, Eastwick bested Tekulve by a few pounds, but he still looked more like the 98-pound weakling than the second coming of Jack LaLanne. Eastwick’s face didn’t give him any additional toughness either. And for those who enjoy Hollywood history, Eastwick had the kind of baby face that would have made Barbara Stanwyck jealous.

Then there’s the name. Rawly Eastwick, short for Rawlins Jackson Eastwick III, makes one think of English royalty, or might even conjure up memories of that clever 1987 film, The Witches of Eastwick, which starred Jack Nicholson in a devilish role. It sure doesn’t sound like the kind of name that we should be seeing on the front of a Topps baseball card.

The face and the name didn’t fit baseball, but Eastwick’s right arm did. At his peak, he could throw with the best of them. And off the field, he had talents to match his pitching skills.

Intelligent and well spoken, Eastwick now lives in Boston, where he manages a series of office buildings. His name entered the public consciousness again in 2013, when he was planning to attend the Boston Marathon. He had wanted to be at the finish line, where he could greet some of the girls who were running in support of NFL player Tedy Bruschi’s charity, known as “Tedy’s Team.” One of the runners was competing on behalf of Haylee Eastwick, Rawly’s daughter, who had suffered a stroke five years earlier. Eastwick had to cancel the greeting when he learned about the terrorist bombing at the finish line of the Marathon.

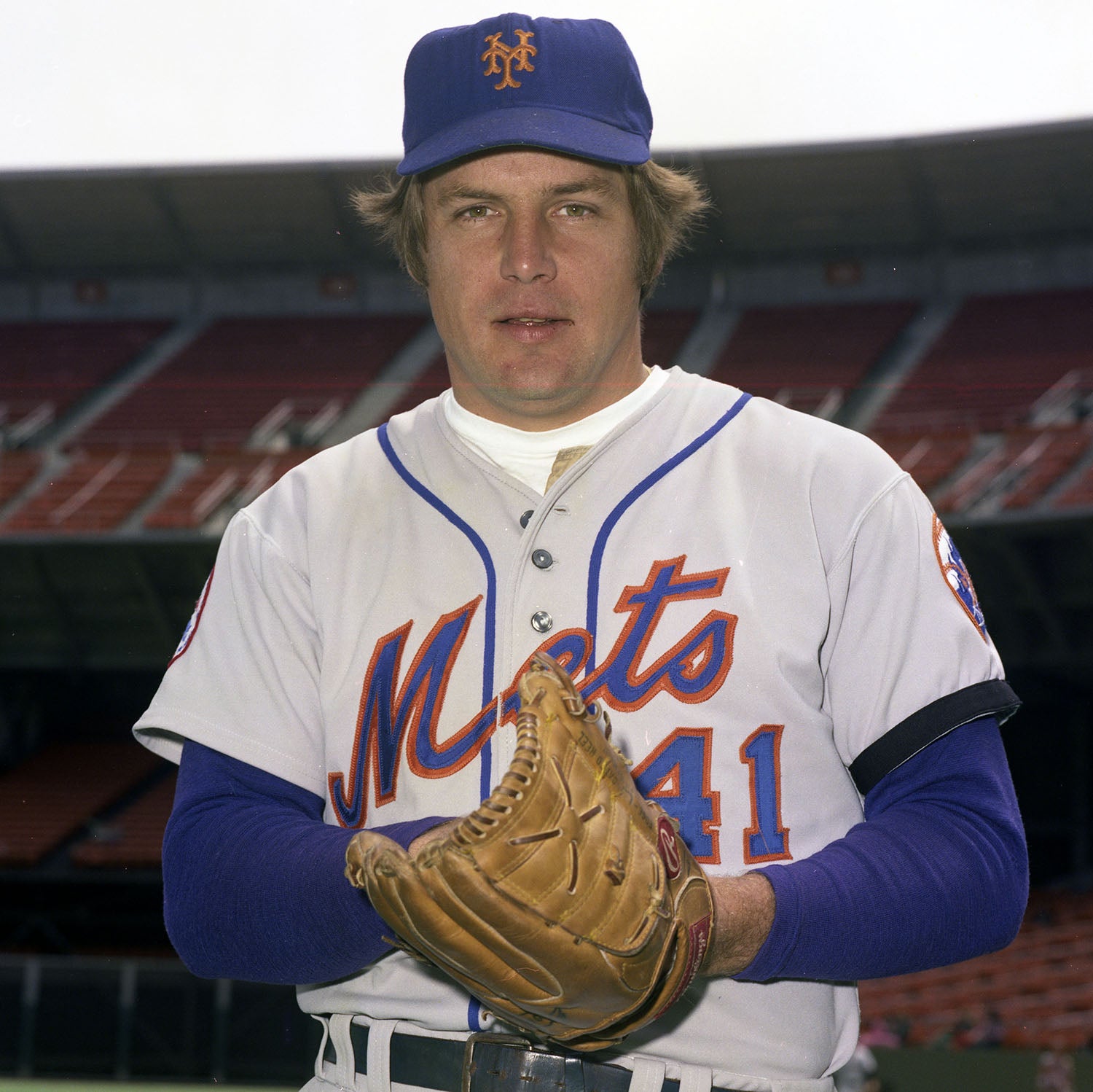

Long ago, Eastwick had far less serious matters on his mind. At the time that this Topps card was released, in the early spring of 1978, Eastwick had just become a wealthy man. He had signed a generous free agent contract with the New York Yankees. But the Topps card does not reflect Eastwick’s signing. Instead, it shows him sporting the airbrushed colors of the St. Louis Cardinals, for whom he had finished out the 1977 season after a mid-year trade from the Cincinnati Reds. (The Reds, having given up hope of re-signing Eastwick as a free agent, traded him to St. Louis for left-hander Doug Capilla. The trade didn’t receive much publicity because it happened the same night that the Reds acquired future Hall of Famer Tom Seaver from the New York Mets.)

Eastwick finished out the 1977 season in St. Louis before cashing in his free agent chips. The Yankees signed him during the winter, even though they already had two other standout relievers in Sparky Lyle and newly signed future Hall of Famer Goose Gossage.

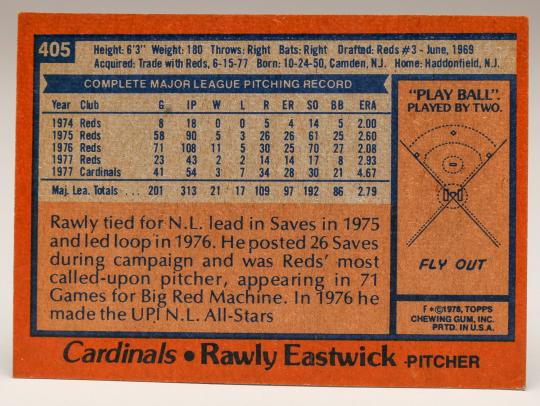

At one time, Eastwick had been a standout relief ace for the Reds. Drafted in 1969 by Cincinnati, Eastwick made his major league debut five years later. Appearing in eight late season games, he flashed the kind of right arm that would become critical to the Reds during their mid-1970s dynasty. In 17 innings, he struck out 14 batters and posted an ERA of 2.04.

Using a three-quarters delivery, an overwhelming fastball and a hard slider, Eastwick emerged as a dominant late-inning reliever in 1975 and ’76. He led the league in saves in 1975 and placed third in the National League Rookie of the Year balloting, but he did run into some trouble in that year’s World Series. In the iconic Game 6 at Fenway Park, Eastwick surrendered a three-run home run to pinch-hitter Bernie Carbo, allowing the Boston Red Sox to tie the game on their way to Carlton Fisk’s game-ending home run.

Ultimately, that inglorious moment didn’t prevent the Reds from winning the Series. The following summer, Eastwick more than redeemed himself by tying for the league lead in saves, winning 11 games, and lowering his ERA to 2.09. While the Reds’ power-hitting attack garnered most of the headlines, Eastwick played a quiet but key role in the Reds winning back-to-back championships.

In 1977, Eastwick lost some life on his fastball. At the June 15 trading deadline, the Reds dealt him to St. Louis, where he struggled for the balance of the season. The Cardinals did not resign him, allowing him to test the free agent waters. That’s how he landed in New York.

Eastwick did not become one of the most integral member of the 1978 World Champion Yankees, as he made only a handful of relief appearances. Eastwick’s early-season presence in pinstripes, however, did provide one of the first controversies of that tumultuous summer. With Eastwick, Gossage, and Lyle all on the ’78 roster to start the season, manager Billy Martin had an overload of ace relievers. Martin picked Gossage to close most of the time (sticking with him despite an early season slump), employed Lyle in a late-inning set-up role, and Eastwick had few opportunities.

It’s not that Eastwick pitched badly in his eight Yankee appearances. He merely became a hood ornament in Martin’s game plan, where starting pitchers piled up loads of innings and only Billy’s best relievers received the ball in meaningful situations. If only Eastwick were pitching in today’s game; he would have been the ideal seventh inning man, setting up Lyle for the eighth and Gossage for the ninth.

The easygoing Eastwick made a number of friends among his Yankee teammates, but Martin never seemed to gain trust in pitching him. Crowded out of the New York bullpen, Eastwick became expendable. The Yankees dealt him to the Philadelphia Phillies for outfielder Jay “Moon Man” Johnstone and minor league outfielder Bobby Brown. In a way, the trade fulfilled a dream, in that Eastwick had once dreamed about playing for the Phillies. Having grown up in Haddonfield, N.J, Eastwick had often attended games with his father at Connie Mack Stadium. Yet the Phillies didn’t scout Eastwick aggressively and never even approached him as he pitched in the amateur ranks.

Unfortunately for Eastwick, the Phillies’ 1978 bullpen was almost as full as New York’s. With Gene Garber, Tug McGraw, and Ron Reed available to soak up the late innings, opportunities for Eastwick continued to dwindle - as did his fastball. Perhaps done in by the 204 innings he logged in 1976 and ’77, Eastwick never regained his dominance while with the Phillies, the Kansas City Royals, or the Chicago Cubs and found himself out of baseball by 1981.

Outside of his meteoric success with the “Big Red Machine” and his brief dalliance with the Yankees, the pencil-thin right-hander created interest because of his offbeat habits. Eastwick practiced transcendental meditation, something he had done ever since childhood in an effort to rid himself of anxiety. Also, during his first spring with the Yankees, Eastwick bragged about a new diet that he had started. It was a regimen that eliminated red meat and foods containing preservatives or dyes, which was a relatively radical diet for the time period.

During the winters, Eastwick spent much of his time collecting antiques, which included a 100-year old ring and Persian money clips. Perhaps most notably, Eastwick showed an aptitude for creating art. He liked to make sculptures. He also created paintings on canvas. Particularly accomplished with the paint brush, Eastwick said that his best painting was a still-life that he gave to Hall of Famer Johnny Bench and his wife as a wedding gift.

It was just another aspect of Eastwick’s life that made him anything but the stereotypical ballplayer.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum