- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1973 Topps Bob Moose

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Bob Moose

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

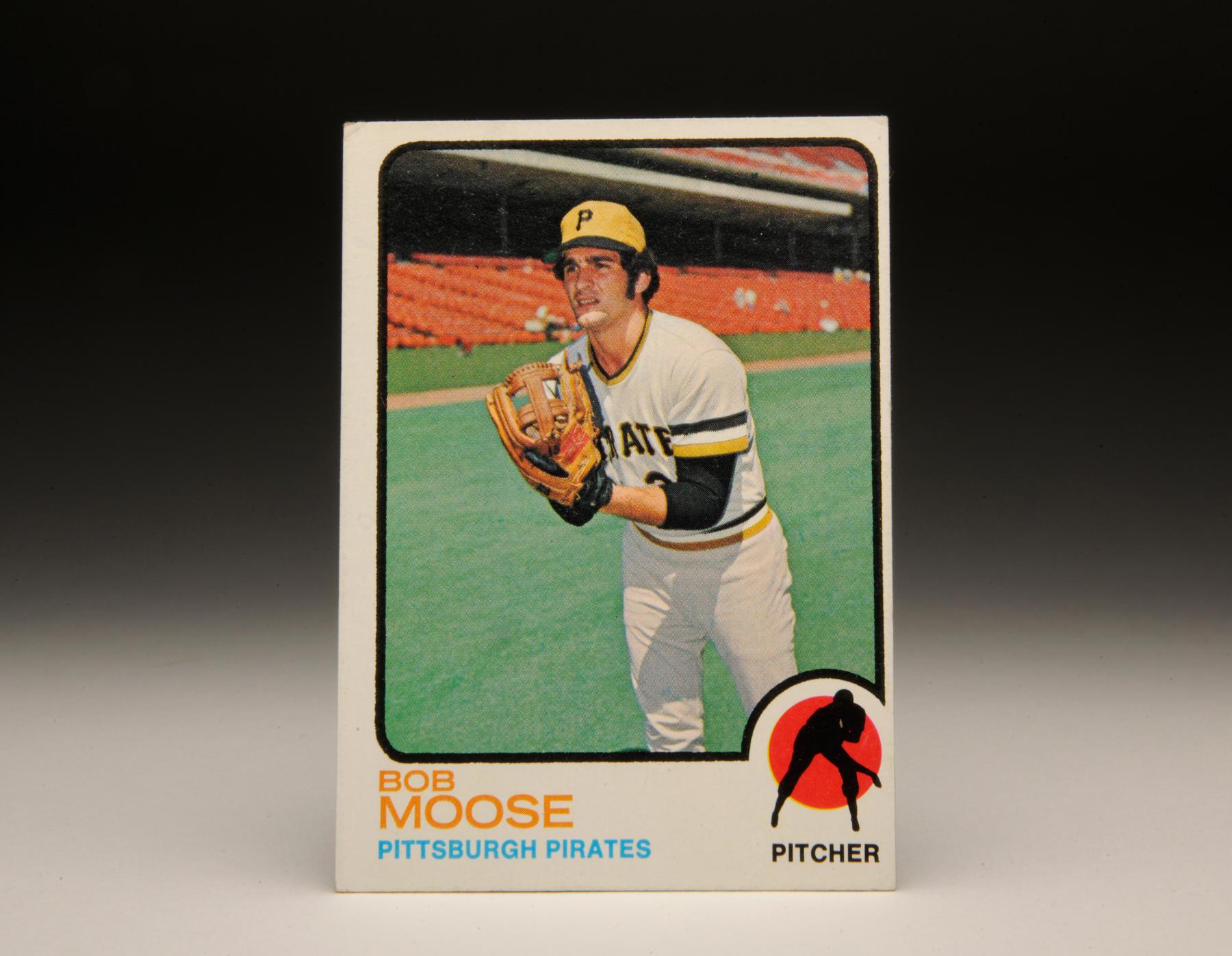

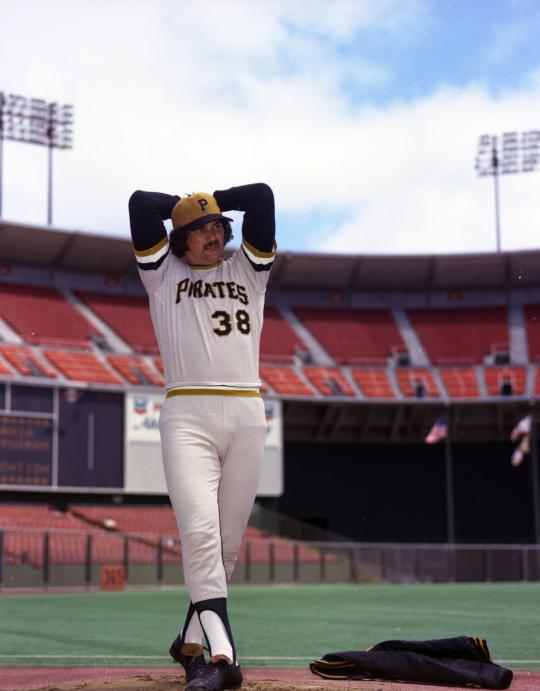

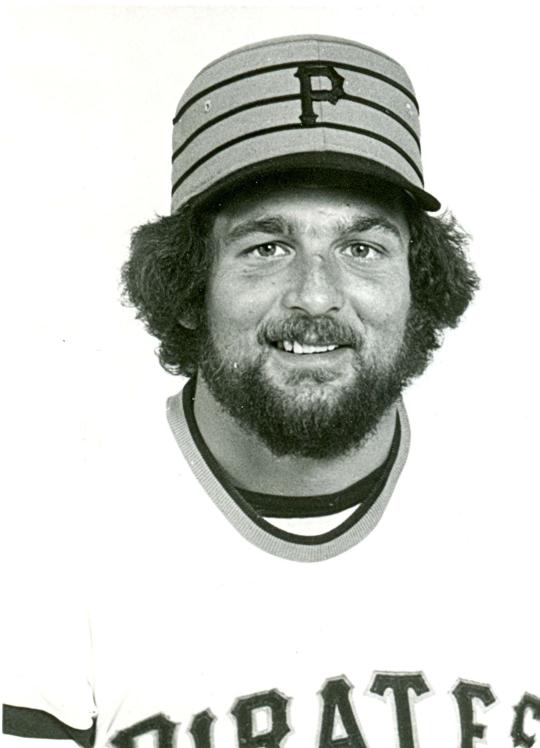

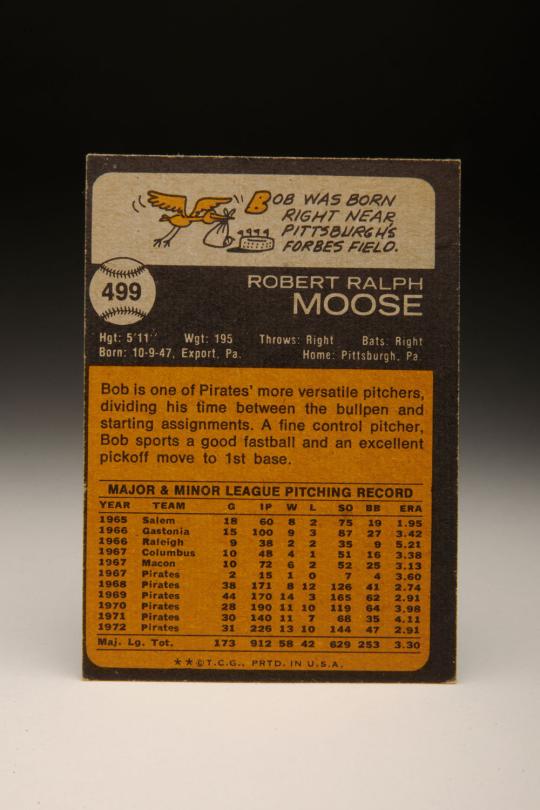

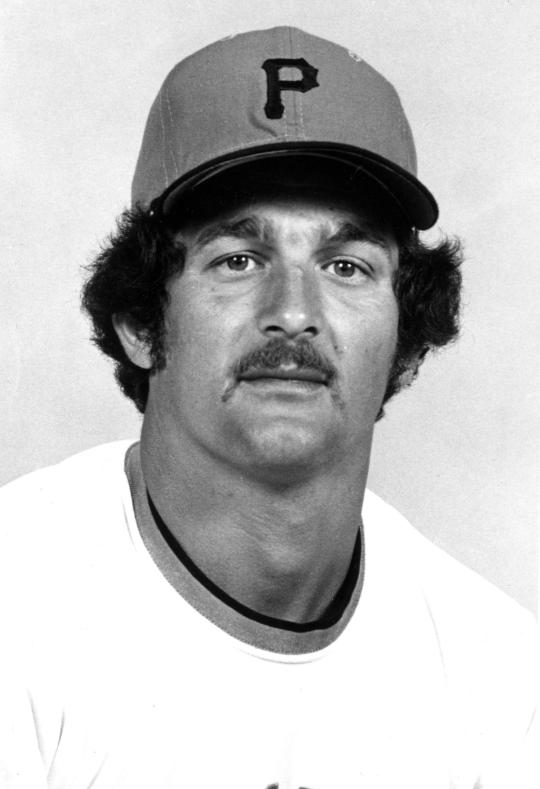

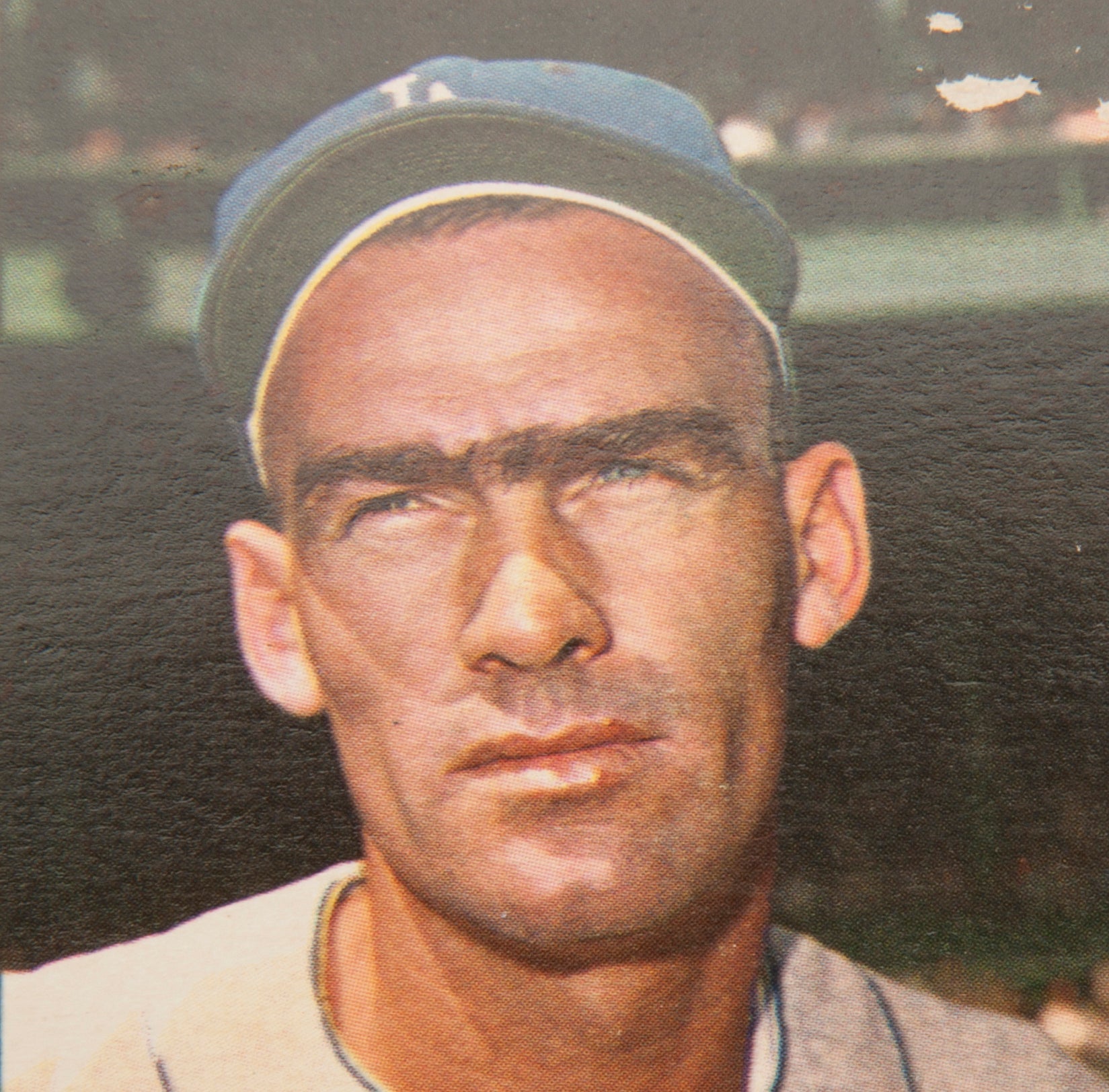

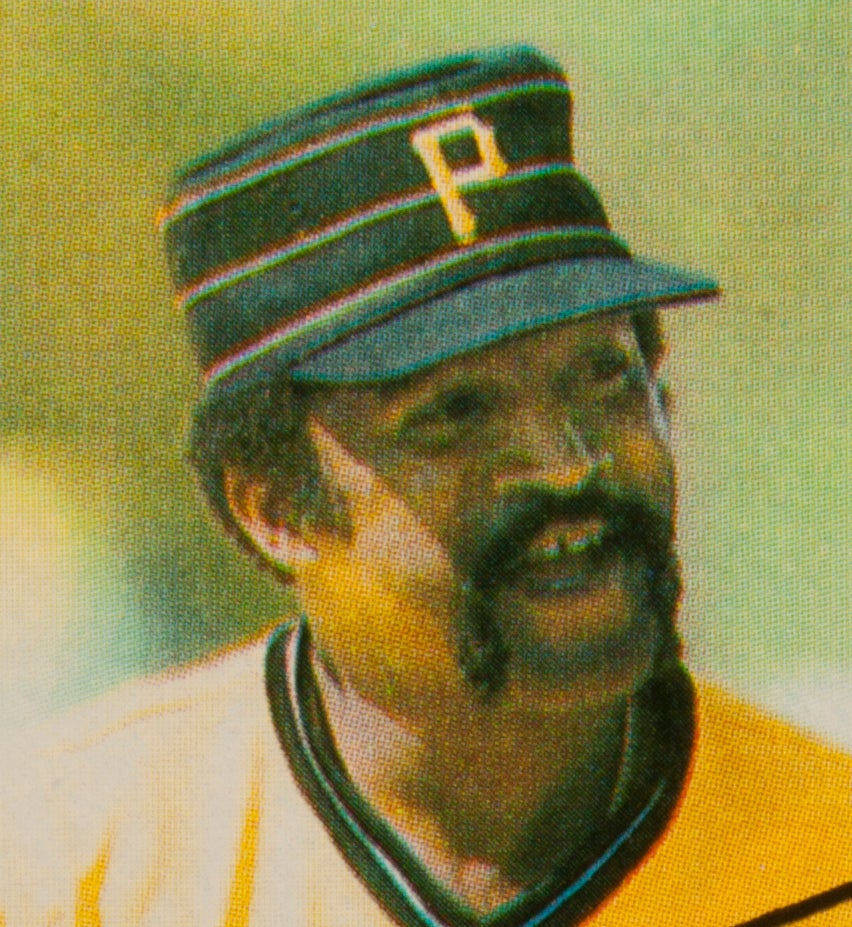

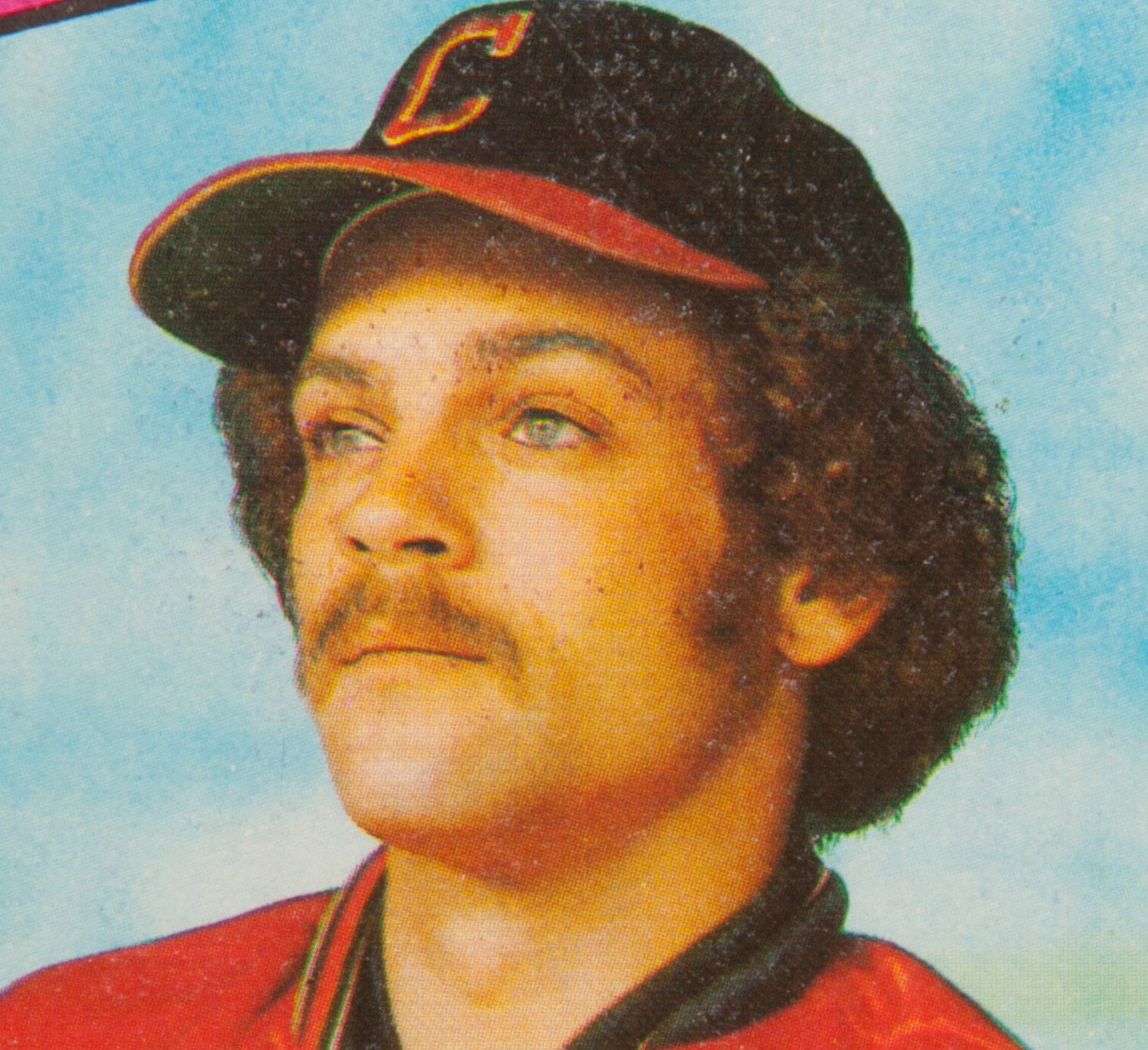

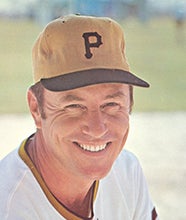

Perhaps no other player epitomized the changes in 1970s hairstyles and general grooming more than Bob Moose. At the start of the decade, Moose wore his hair short and neat, much like the vast majority of players in the still-conservative major leagues. But by 1973, Moose’s look had begun to change. As we see on his accompanying Topps card, Moose’s hair is beginning to look bushy under his Pittsburgh Pirates cap and his sideburns are starting to lengthen. By the time his 1974 card came out, Moose’s hair was so long that it looked much like an Afro. He had also grown a mustache by then, continuing a trend that had started with Dick Allen in 1970 and had reached league-wide proportions by the mid-1970s.

By 1976, Moose’s final year in the big leagues, he had added a beard to his repertoire, completing the transformation. He was certainly not the only ballplayer to take on that look in the year of the Bicentennial, but he might have been the only one who had changed his appearance in such an orderly progression over the first half of the decade.

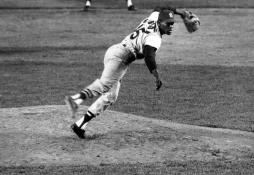

When Moose’s Topps card came out in the spring of 1973, fans of the Pirates didn’t care much about how he looked on the card. They were still reeling from what had happened the previous fall, when Moose’s wild pitch resulted in a heartbreaking five-game Championship Series loss to the Cincinnati Reds. In the ninth inning of Game 5, Moose faced Hal McRae, who was still a young, unproven bench player trying to find his way. With the game tied and two men out, George Foster led off third base, representing the pennant-winning run. Moose uncorked a fastball low and outside to catcher Manny Sanguillen, who made a valiant backhanded effort, but couldn’t block the errant pitch. As the ball trickled to the backstop, Foster sprinted home with the series-ending run.

As he reported to 1973 Spring Training in Bradenton, Fla., Moose waded through a sea of questions from Pittsburgh writers about the events of the previous fall. Moose did his best to shrug off the experience, but found it difficult. “The only thing that bothers me now is that people... that’s all they want to talk about,” Moose told the Associated Press. “I threw better [than that] all year, and they want to talk about one pitch.” Moose wasn’t angry about the situation, but he was a bit frustrated with the obsession over one pitch, which had come several batters after the Pirates had already coughed up a ninth-inning lead against the Reds.

Still, Moose did his best to keep his perspective about the pitch. “For about 10 minutes after the game, the pitch disturbed me,” Moose once told the Sporting News. “Then I realized it was just part of the game. I didn’t have any trouble living with it.”

It’s easy to forget that the Pirates had summoned Moose as a reliever in that game even though he had pitched as a starter practically all season. In fact, he made only one relief appearance during the regular season. But Moose would always take the ball from his manager, no matter the situation. Starting, relieving, tired, or fresh, Moose didn’t care. Just give him the ball, and he would make no excuses.

An important part of the Pirates’ rotation in 1972, Moose had carved out an ERA of 2.91 while striking out 144 batters in 226 innings. It was just the latest sampling of good work from the bulldog right-hander. He stood only five feet, 11 inches tall, but owned a live fastball, a good curveball, a decent slider and terrific control. Talented and tough, Moose had already led the National League in winning percentage in 1969, thrown a no-hitter against the New York Mets, and come back from arm trouble to help the Pirates win the 1971 world championship as a valuable combination starter/reliever for manager Danny Murtaugh.

Bothered by a sore knee, Moose fell to 12-13 in 1973 and saw his era climb to 3.53. That winter, he underwent an operation to remove some cartilage in the knee. The following summer, a more serious problem ensued: a blood clot near Moose’s collarbone sidelined him for most of the season. The clot necessitated two operations, one to remove the actual clot and the other to remove one of his ribs. Although Moose struggled to regain his pitching form after the surgeries, some believed he would still succeed Dave Giusti as the Pirates’ No. 1 relief pitcher.

Moose pitched respectably in 1975, though he was limited to only 23 appearances. He pitched better and more frequently in 1976. Though his velocity was diminished, Moose relied on guile and guts, picked up 10 saves, and managed to stay on the active roster all season. With Giusti fading and Kent Tekulve still unproven, Moose might have emerged as the Pirates’ relief ace in 1977. We’ll never know -- because of the circumstances of October 9.

It was just a few days after the 1976 regular season had ended. Moose and a number of other Pirates had participated in a golf outing earlier in the day. Moose then drove to his hotel room to change clothes before returning to the golf course and restaurant owned by Hall of Famer Bill Mazeroski, who was hosting a dinner party in Moose’s honor.

As he made his way back to the restaurant, Moose was driving on a narrow, twisting road near Martins Ferry, Ohio. Current and former Pirates teammates like Giusti, Sanguillen, Nellie Briles, Bruce Kison, and Jim Rooker awaited Moose’s arrival at the restaurant. At about 9:30 PM, while driving south on Ohio Route 7, Moose lost control of his car on the rain-slickened road.

According to the police report, Moose was driving too fast given the wet conditions. He swerved onto the bank of the road, then veered back to the left of the center line. His car crashed head-on into an oncoming vehicle. Two women in his car, whom Moose had given a ride because their car had broken down, escaped with injuries, as did the driver of the other vehicle. Moose was not so fortunate. The young pitcher was pronounced dead at the scene. His death, while tragic enough, happened to occur on his 29th birthday. Moose left behind a devastated wife, Alberta, and a young daughter, April.

Richie Hebner, who served in the Marine Reserves with Moose, remembers receiving the tragic news of his teammate’s death. “I’ll never forget, I got a call and someone said, ‘Bob died.’ And I said, ‘Bob? There’s a lot of Bobs [on the Pirates].” Thoughts of roommate Bob Robertson raced through Hebner’s mind. “And they told me [it was] Moose. Geez, I felt so bad, I flew down to Pittsburgh for the funeral, and I tell ya, that was a sad, sad funeral, because at the time I think his daughter was only four years old. It was tough.”

Moose was beloved by his Pirates teammates -- for his tenacity on the mound and his willingness to take things in stride off the field. He was particularly close to fellow pitcher Bruce Kison, who had asked Moose to serve as best man at his wedding in 1971, taking place only hours after the World Series victory over Baltimore.

Moose’s opponents respected him, especially his competitiveness and his willingness to pitch in pain. “Bob Moose was my kind of player,” said Pete Rose, who had faced Moose as a member of the Reds in the 1972 playoffs. “He would fight you to the bitter end.”

A little more than two months after his death, friends and teammates of Moose announced plans to establish the “Bob Moose Memorial Fund,” which was designed to pay for the education of Moose’s daughter and establish a scholarship at Moose’s high school alma mater.

Pirates standout Al Oliver, the chairman of the fund, was one of Moose’s closest friends on the Bucs. He always applauded Moose for the way he handled himself after the wild pitch that ended the Pirates’ season in 1972. “Moose didn’t go into hiding after that pitch,” Oliver told the Sporting News. “He walked off the field with his head high. Later in the clubhouse, he didn’t hide from reporters. He answered every question and he didn’t alibi. He was a pro.”

Oliver also remembered Moose for the encouragement he offered teammates. “When I was down, maybe for not hitting,” Oliver recalled, “Moose would find a way to talk to me. I appreciated that.”

While Moose’s physical appearance changed drastically over the last few years of his life, his character didn’t. That never wavered, never changed. He remained a tough pitcher, a solid teammate, and an encouraging friend to his Pirates mates until the moment he left them.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame