- Home

- Our Stories

- Catfish Hunter signs free agent contract with New York Yankees

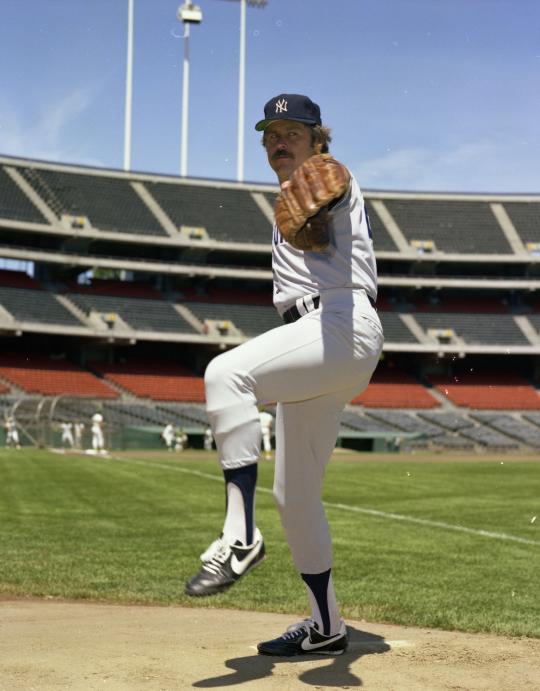

Catfish Hunter signs free agent contract with New York Yankees

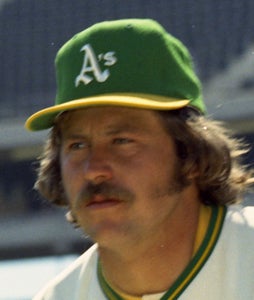

By the end of the 1974 season, Jim “Catfish” Hunter was the ace on baseball’s best team. He had just completed a stellar season, capturing the Cy Young Award after leading the American League in wins (25) and earned run average (2.49) and powering the Oakland Athletics to their third consecutive World Series title.

“When we started winning in Oakland, Cat was the father of those teams,” Hall of Famer Reggie Jackson said.

But on Dec. 31, 1974 the future Hall of Famer traded in his bright yellow A’s uniform for Yankee pinstripes, after a dispute over a technicality in his contract with A’s owner Charles O. Finley.

Hunter’s contract with the A’s was straightforward. He was owed $100,000 total in 1974, with $50,000 to be paid to him directly from Finley and the remaining half to be issued in monthly payments on an insurance annuity. Finley, however, was late in delivering the insurance payments, creating strife between owner and pitcher.

The conflict was leaking out to the press by the time Finley, under pressure from Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, finally offered Hunter the insurance payments in a lump sum.

“Charlie said, ‘Here's the money,’” Hunter recalled. “I told him, ‘I don't want it that way. Pay the insurance like the contract read.’”

When Finley rebuffed, Marvin Miller, head of the Major League Baseball Players Association, seized the opportunity. Miller had been following the dispute closely, and recognized that Finley’s breach of contract represented a chance to take Hunter’s case to a neutral arbitrator. If the arbitrator sided with Hunter, the star pitcher’s contract could be voided.

“One thing worried me,” Miller later reflected. “The remedy was free agency. That was drastic. I thought it might be too drastic for an arbitrator.”

In 1974, baseball was still operating under the reserve clause, which stipulated that a team retained complete control of a player unless he was given his unconditional release. The most recent challenge to the reserve clause, made by St. Louis Cardinals outfielder Curt Flood, had been denied by the U.S. Supreme Court two years before.

Hunter’s case was brought before arbitrator Peter Seitz in December, and Finley claimed to be confused by the terms of Hunter’s contract.

“My confidence grew as the hearing developed,” Miller said. “Seitz was a perceptive, acute man. It was clear he was not buying Finley's story, when Charlie said he knew nothing about this and claimed he did not understand the deferred payments.”

On Dec. 16, Seitz formally upheld Hunter’s grievance but failed to mention the crucial out clause that would grant the pitcher freedom. After further persuasion from Miller, Seitz spelled out a remedy in his ruling: Hunter would become the first free agent in baseball’s modern era.

Hunter admitted he was partially stunned when he learned of Seitz’s ruling. “I hung up the phone, turned to my wife and said, ‘We don't belong to anybody.’ I was scared. I didn't have a job. I didn't realize the implications.”

For the first time since the 1870s, a major league player was free to offer his services to the highest bidder. Twenty-two of the remaining 23 teams – all but the San Francisco Giants – entered the sweepstakes for baseball’s best big game pitcher. Some owners even flew to Hunter’s country home in North Carolina to woo the star right-hander.

“(California Angels owner) Gene Autry came down here handing out records of ‘Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,’” Hunter said. “That was the biggest thing that ever came to Ahoskie (N.C.).”

The bidding war reached its climax on New Year’s Eve, when the New York Yankees announced that they had landed Hunter. While the union of baseball’s most famous team and perhaps its most famous pitcher was intriguing enough, the price tag was the true headline: A five-year deal worth about $3.2 million, along with a $1 million signing bonus.

In addition to the money, Hunter got the bonuses he was looking for – including guaranteed insurance payments and annuities for college tuition for his two children. Furthermore, he was joining an organization that was hungry to regain its former glory.

“To be a Yankee is a thought in everyone’s head and mine,” Hunter said. “Just walking into Yankee Stadium, chills run through you. I believe there was a higher offer, but no matter how much money offered, if you want to be a Yankee, you don’t think about it.”

Without its ace, Finley’s A’s would fall to last place by 1977. The Yankees, meanwhile, were revitalized by their new addition. Hunter would lead them to three consecutive pennants and back-to-back World Series titles in 1977-78, restoring the Bronx Bombers to the top of the baseball world.

“You started our success,” Yankees owner George Steinbrenner told Hunter upon the pitcher’s induction to the Hall of Fame in 1987. “You were the first to teach us how to win.”

The ramifications of Hunter’s landmark contract, meanwhile, were felt outside the Bronx. In 1975, pitchers Dave McNally and Andy Messersmith played without contracts. The following winter, Seitz declared them to be free agents, effectively ending the reserve clause and bringing about the first free agent player draft on Nov 4, 1976.

“I was probably the first player who broke it open for other players to be paid what they're worth,” Hunter said.

Matt Kelly was the communications specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum