“It’s the fact that Ruth’s impact goes so far beyond baseball that makes him truly exceptional.”

- Home

- Our Stories

- Making of a Legend

Making of a Legend

To understand the man, you first must understand the legend.

George Herman Ruth overshadowed the game – and remains to this day the very essence of baseball. His career, on and off the field, made him one of the most famous Americans to have ever lived.

He is the definition of a “Hall of Famer.”

“Babe Ruth is not just a legend now, he was a legend in his own time,” said Hall of Fame senior curator Tom Shieber. “That’s rare. And that’s a big reason why we’ve got an exhibit dedicated to only him.”

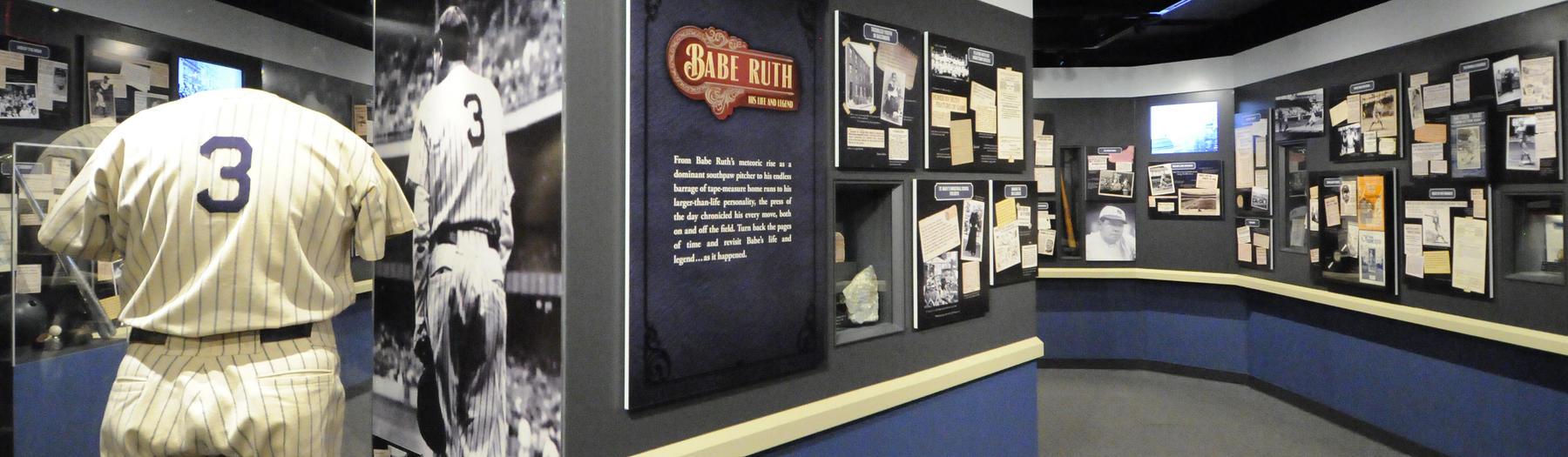

The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum has long allocated precious exhibit space to Ruth, a member of the Hall’s inaugural Class of 1936. In the spring of 2014, the 180-square foot Ruth exhibit was re-curated to bring new life – and a new light – to one of baseball’s most familiar stories as baseball celebrated the 100th anniversary of his big league debut on July 11, 1914.

“If you’ve been to the Museum before, you won’t recognize the exhibit even though it will be in the same space,” said Shieber, the Ruth exhibit’s lead curator who is charged with sifting through hundreds of Ruth artifacts and ephemera to create the new second-floor time capsule. “As a team, we started out with what seemed to be a simple question: ‘Why do an exhibit on Babe Ruth?’

“The answer – his status as a legend – constantly informs us as we go about making choices for the exhibit.”

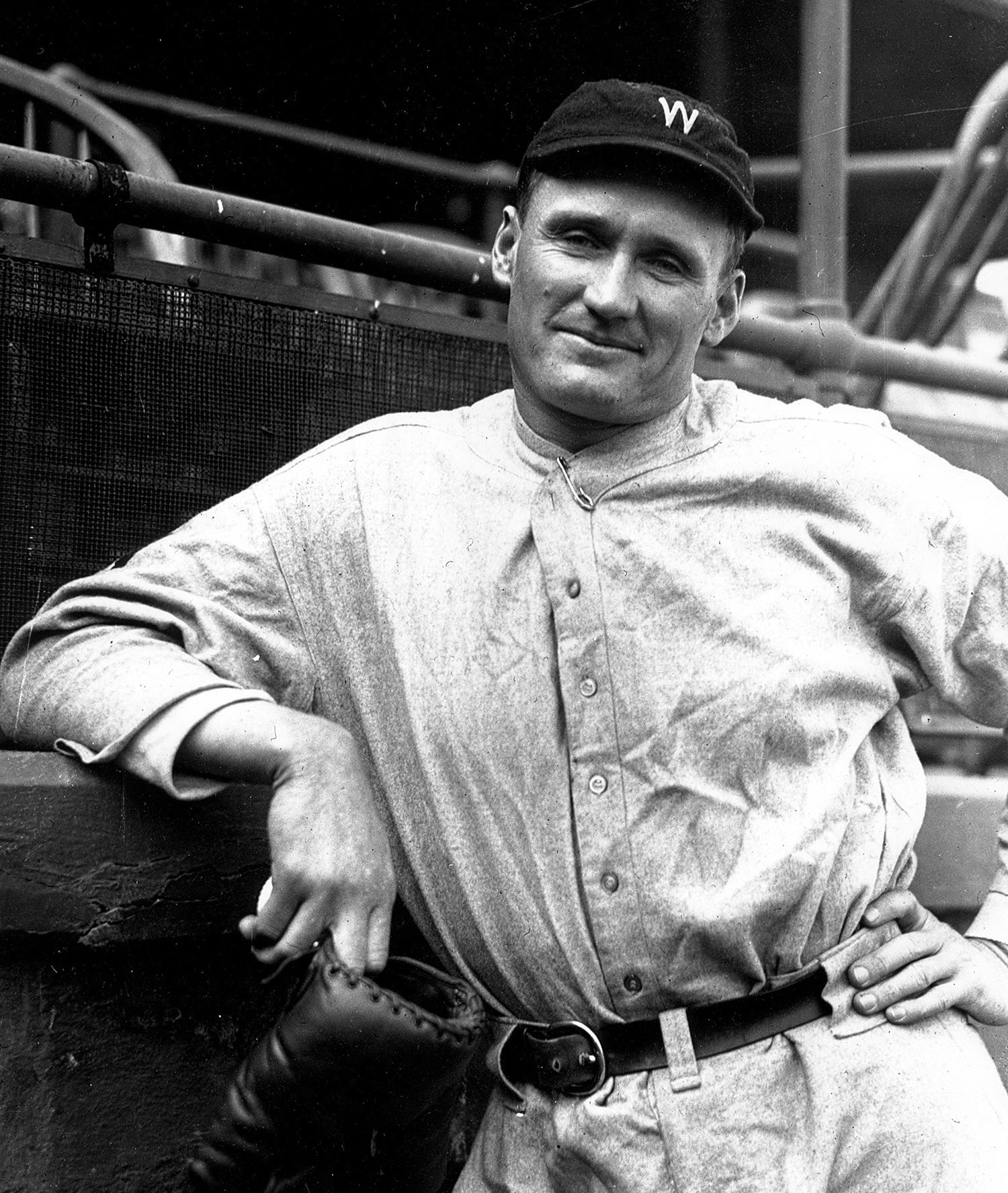

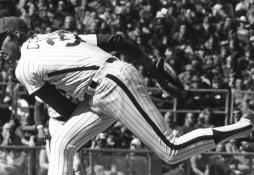

Born Feb. 6, 1895 in Baltimore, Md., Ruth came of age as mass communication devices like radio and movies shrunk the distance from sea to sea. As a young left-handed pitcher with the Red Sox, he was one of the game’s heroes. But later as a power-hitting outfielder for the Yankees, Ruth became an icon – transcending sport.

Ruth became the first star of a world where virtually every citizen could share in common media experiences. The Museum’s new exhibit will give visitors the chance to encounter Ruth’s grandeur in the words of the people who saw it.

“The design of this exhibit is very different than anything we’ve ever done before,” said Erik Strohl, the Museum’s vice president for exhibitions and collections. “It (borrows) from the concept of a scrapbook, where you can read about Ruth through contemporary sources such as real newspaper stories, historic photographs and rare ephemera.

“It (looks) at Ruth as if you were back in his own time. You’ll be there to get a first-hand sense of his legend.”

Ruth’s legend was built on the diamond. After three dominant seasons in Boston as a pitcher – where he won 65 games from 1915-17 and was widely considered the game’s best left-hander – Ruth transitioned to the outfield, where he led the American League in home runs with 11 in 1918 before hitting a record 29 home runs in 1919.

Prior to the 1920 season, the Red Sox sold Ruth to the Yankees – planting the seeds of a dynasty. With 54 home runs in 1920 and 59 more in 1921, Ruth captured the attention of a nation.

But Ruth’s legend was more than just numbers. He became an oversized symbol of America’s power, a brilliant man with human flaws that made him seem more real than mythic.

The new exhibit will feature artifacts that tell both sides of this story, such as a trophy presented to Ruth by his “Baltimore admirers” on May 20, 1922.

“You look at this beautiful trophy and immediately recognize that it is special,” Shieber said. “What you may not recognize is the date. May 20, 1922 was the day Ruth returned to the Yankees after being suspended for the start of the season by Commissioner Landis for illegally barnstorming after the World Series. Fans from his hometown made the nearly 400-mile trek to New York just to welcome him back to the big leagues.

“It’s stories like that which fill out the picture of his legend and what he meant to America.”

The exhibit features documents like:

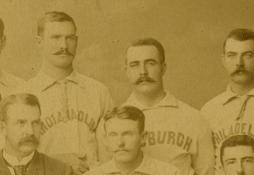

The contract that transferred Ruth, Ernie Shore and Ben Egan from the Baltimore Orioles of the International League to the Red Sox on July 11, 1914.

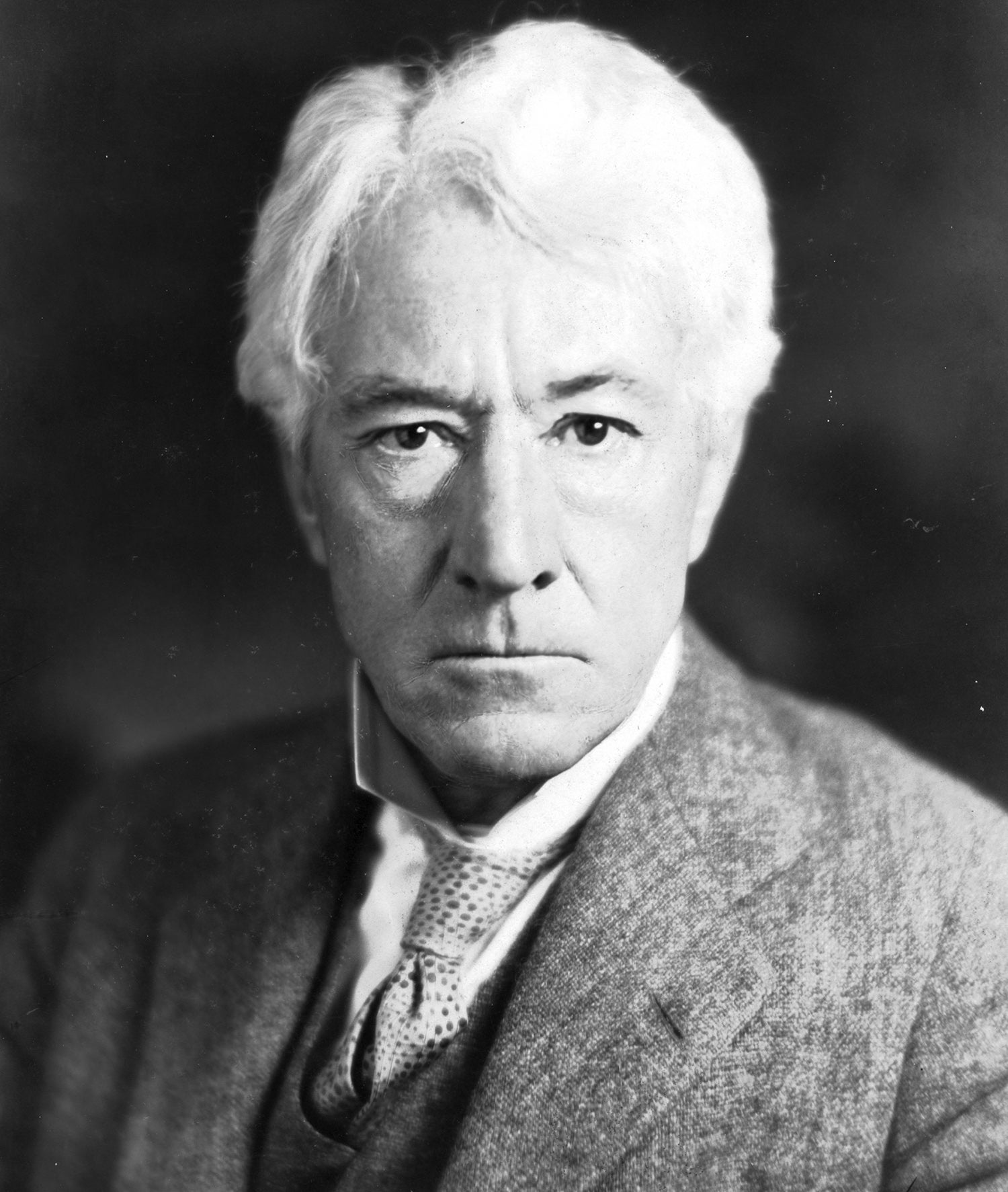

The type-written notes used by AL president Will Harridge for his speech on Babe Ruth Day at Yankee Stadium on April 27, 1947. Harridge – himself a Hall of Famer – typed the words: “To say ‘Babe Ruth’ is to say ‘Baseball’”

The exhibit also contains one of the most famous jerseys Ruth ever wore – but one that never saw a big league game.

“We have his jersey from June 13, 1948 – when Ruth’s No. 3 was officially retired,” Shieber said. “That day, after the ceremony at Yankee Stadium that featured the Pulitzer Prize-winning Nat Fein photo of Ruth standing on the field, Ruth gave the jersey he wore to a Hall of Fame representative. Through research conducted last year, we determined that the jersey was one he wore throughout his retirement – starting with his cameo appearance in “Pride of the Yankees” in 1942. It was a movie costume, but the Babe wore it over the next few years at benefit games, like one where he faced Walter Johnson in a drive for war bonds and another where he met Ted Williams for the first time.

“I cannot imagine a more important or significant non game-used uniform.”

When cancer claimed Ruth’s life in 1948, he was only 53 years old. Yet the tales of his legend were enough to fill multiple lifetimes – and continued to grow along with the game itself.

Ruth embodied the country that had given a poor young boy the chance to rise as high as his talents would take him.

Other ballplayers have had one or two legendary moments, but Ruth collected them by the dozen. Perhaps his most famous was the “Called Shot Home Run” from the 1932 World Series. “Historians still argue whether or not Ruth really predicted the home run just seconds before he hit it,” Shieber said. “But, even if we discovered definitive proof that his Called Shot did not happen, the story would still resonate. It would still be legendary.

“It’s the fact that Ruth’s impact goes so far beyond baseball that makes him truly exceptional.”

So far beyond baseball, in fact, that the borders of his own country could not hold Ruth’s legend.

“There are accounts of Japanese troops attacking American soldiers in World War II yelling ‘To hell with Babe Ruth!’” Shieber said. “They weren’t yelling ‘To hell with FDR!” They knew that it invoking Ruth’s name would mean something much more.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum