- Home

- Our Stories

- Monte Irvin Remembers

Monte Irvin Remembers

While Monte Irvin excelled at the big league level, there’s always been the thought that fans during the 1950s didn’t get to see him at his best.

Due to the “color line” in the big leagues prior to Jackie Robinson’s debut in 1947, Irvin, who arguably spent his prime seasons toiling in the Negro Leagues, didn’t make his debut in the majors until after his 30th birthday. Though he might be overlooked today when debating the greats of the game, when finally given the chance he proved he belonged among the best.

In 1976, when U.S. President Gerald Ford urged Americans to join in observing February as Black History Month, he could have used Irvin, a ballplayer who overcame his segregation and became a trailblazer in the sport’s highest office, as an example of the progress made by African Americans over the previous decades.

“The last quarter-century has finally witnessed significant strides in the full integration of Black people into every area of national life,” Ford said in his statement.

“In celebrating Black History Month, we can take satisfaction from this recent progress in the realization of the ideal envisioned by our founding fathers. But, even more than this, we can seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of Black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history.”

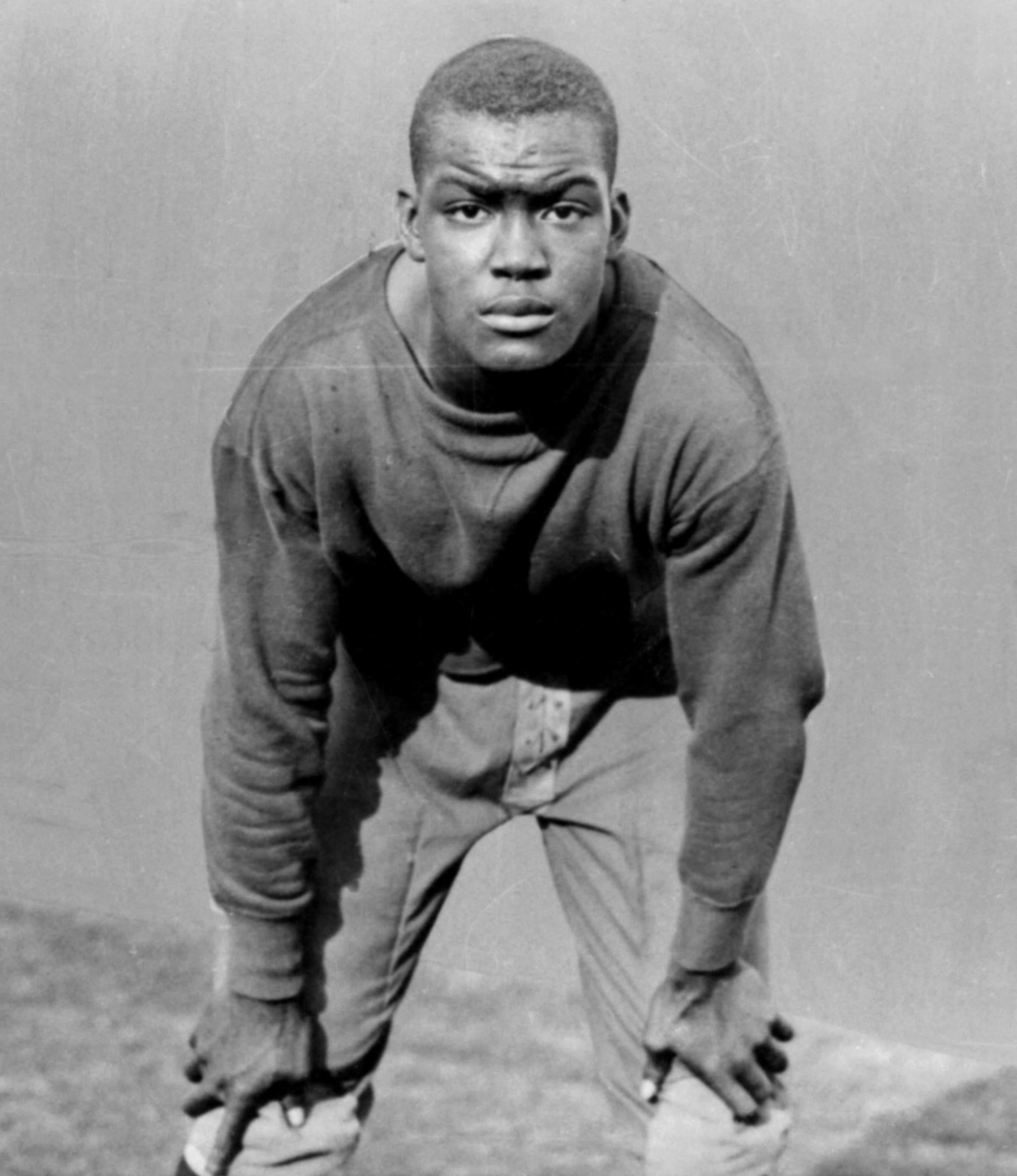

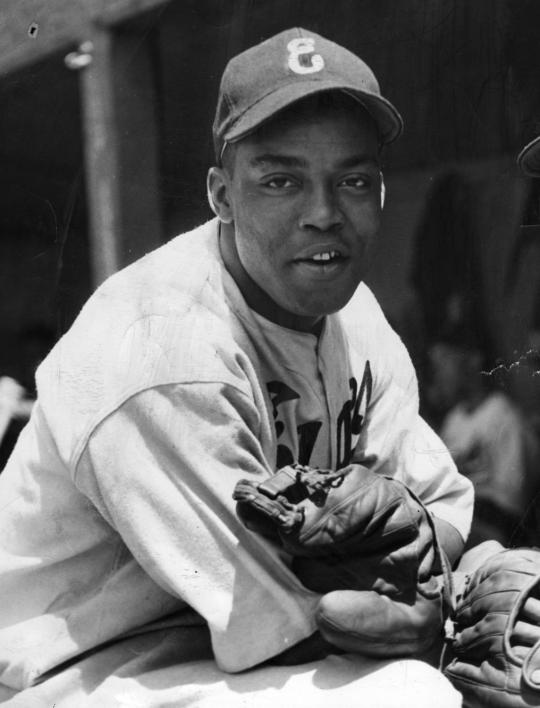

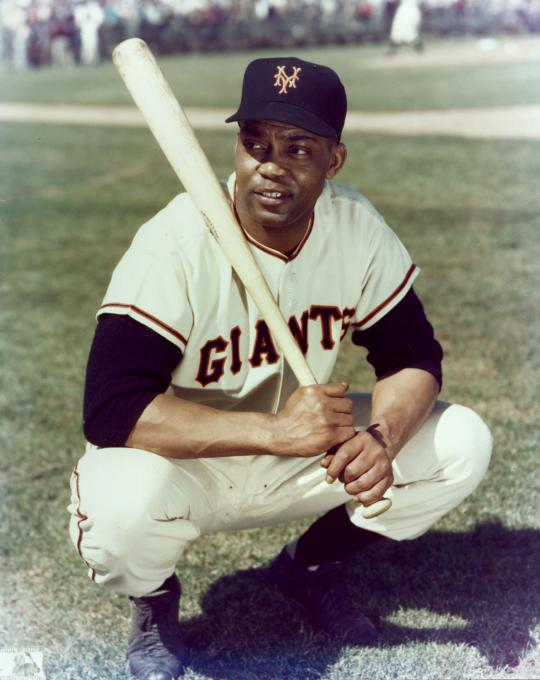

Born to a sharecropper’s family in Alabama in 1919, Irvin would become a four-sport star (football, basketball, baseball and track) at Orange (N.J.) High School. A Negro Leagues sensation with the Newark Eagles, Irvin also thrilled crowd while playing in Mexico and Cuba before signing his first big league contract with the New York Giants prior to the 1949 season.

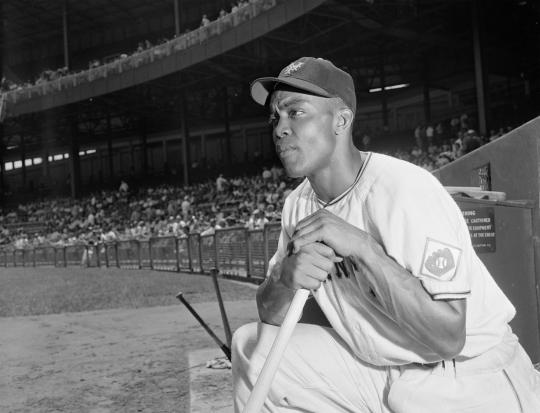

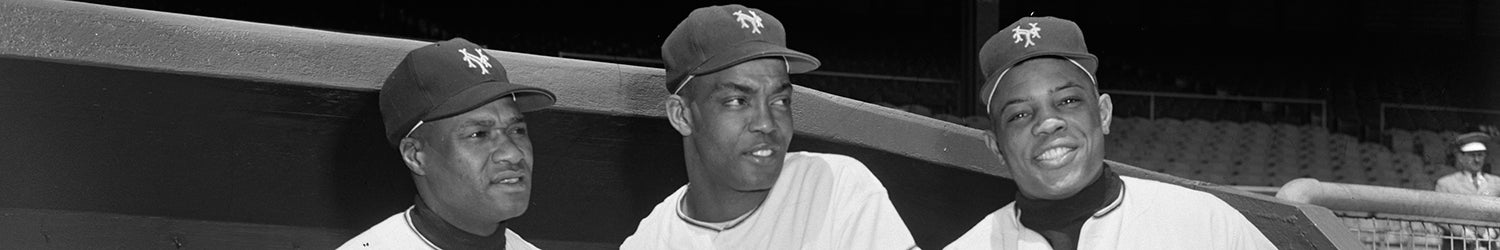

Monte Irvin of the New York Giants looks on from the dugout. (Osvaldo Salas / National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Share this image:

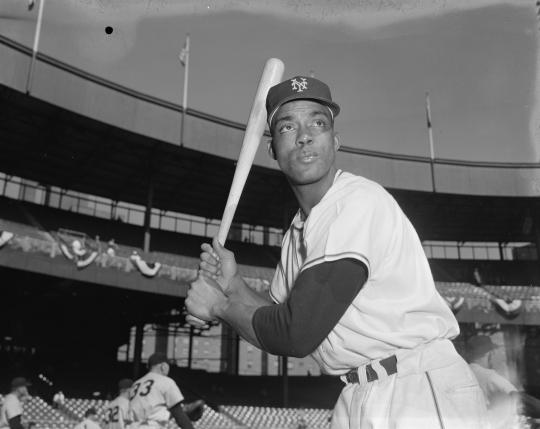

Starring in both the National and Negro National leagues, Hall of Famer Monte Irvin straddled the pre- and post-integration eras. After nine seasons in the NNL, Irvin joined Ford Smith as the first black ballplayers to sign with the New York Giants. (Osvaldo Salas / National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Share this image:

By 1951, Irvin’s offensive numbers were among the best in the game – 174 hits, .312 batting average, 24 home runs and a league-best 121 RBI – helping him finish third in the senior circuit’s MVP voting. That was also the year the Giants used a late-season charge against the Brooklyn Dodgers to create one of the most famous pennant races in the game’s storied history. Irvin not only was a key figure down the down the stretch in 1951, but after the Giants’ playoff victory over the Dodgers, he batted .458 in a losing effort against the New York Yankees in the World Series.

Oral History in Cooperstown

Thanks to the oral history collection of the Baseball Hall of Fame Library, today’s fans are able to listen to those associated with the game, in their own voice, talk about their life on and off the field. In August 1988, State University of New York at Oneonta professor Rod Roberts, on behalf of the Hall of Fame, conducted on such oral history interview with Irvin:

“I started [with the Eagles] in 1937 when I was still in high school and I played on the road. Wouldn’t play at home. Didn’t want to lose my amateur standing, but that was common in those days because you used an assumed name. No television, no radio. The games weren’t broadcast so very rarely would anybody know you. Very few fellows got caught because your picture didn’t appear in the paper. Now at home I would work out and when the game started I would just get dressed and go sit in the stands. That happened up until 1939 when I got out of school. I went on to spring training with them and then became a full-fledged member of the team.”

Irvin’s response was definitive when asked if he ever thought about playing in the major leagues back then.

“We never did think we’d be given a chance. We used to play against the major leaguers and they told us that we were good enough to play. We always wondered at that time what the hell is the difference? You play with the same ball and you play on the same field and use the same gloves. Why not? You play integrated sports in school. Why not play in organized ball? We figured out maybe they just didn’t want us to make any money.

“We were hopeful that it would happen but we weren’t very optimistic. In fact, we had some guys that were so good they became a little paranoid about it. ‘Why the hell won’t they let us play? We play them, we beat them, and they still won’t let us play. What does it take for them to realize that we can play just as well as they can?’”

As an example of his poor treatment, Irvin would recall an incident from the day he graduated from high school.

“You’re in a democracy and you go to school and the teacher is drilling into you about fair play and the moment you get out of school they discriminate against you. What the hell kind of system is that? I brought great honor to my city (Orange, N.J.) and the night I graduated, four of us went to a restaurant to celebrate about two blocks away from the high school and they wouldn’t let us in. So instead of really celebrating we just went on home and went to sleep because we felt so terrible about it.”

According to Irvin, the prejudice continued even after he finally made it to the majors.

“When I became part of organized baseball we trained in St. Petersburg (Fla.). We couldn’t stay with the team. So I went to Eddie Brannick, our travelling secretary, one day and I said, ‘You know, Eddie, we’re here trying to make the team and look like we’re going to become a vital part of this team. Why are we treated so badly?’ He said, ‘Monte, it’s the state law. Everything is segregated, including the hotels, the restaurants, the theaters and the buses. That’s the way it is and that’s the way it’s going to be until somebody changes it. They haven’t changed it yet. We hope they do.’”

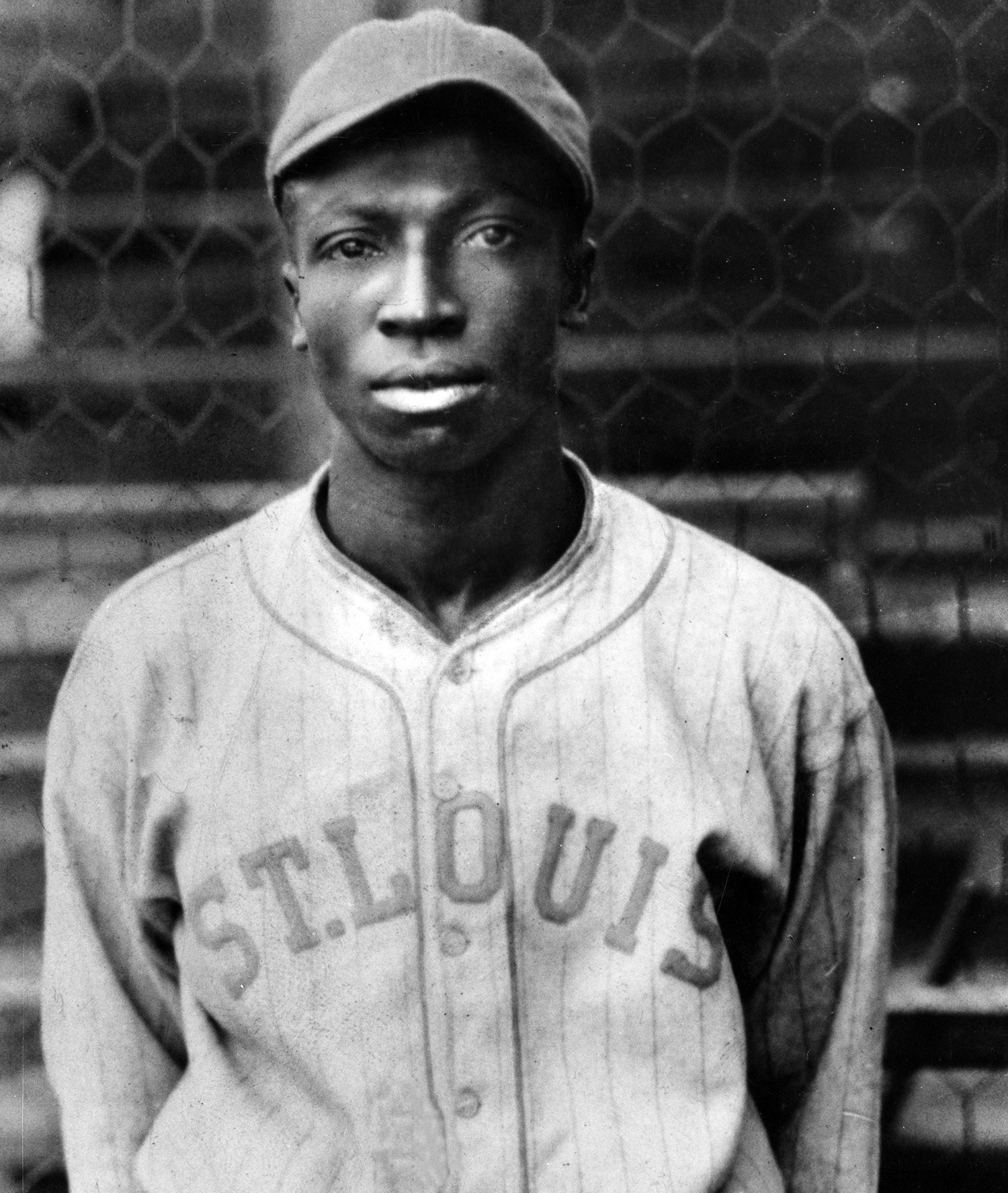

While Jackie Robinson famously broke baseball’s color barrier when he debuted with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947, Hall of Famer and longtime Negro leagues star Cool Papa Bell was quoted as saying, “Most of the Black ballplayers thought Monte Irvin should have been the first Black in the major leagues. Monte was our best young ball player at the time.”

When asked by Roberts if it should have been him instead of Robinson, Irvin said:

“I could do the five things pretty well before the war. It was run, hit, field, throw and hit for power. There wasn’t too many people who could beat me playing. I would have loved to come up sooner because I could really play. I never saw anybody who could beat me playing baseball when I was 18, 19 years old. I could run like a deer, a lot of power, a great arm, and a clutch hitter. I’d have loved to have had a long and illustrious career, maybe play 20-some years, hit 600, 700 home runs, and drive in a lot of runs. But it didn’t happen.”

An Off-the-Field Legacy

Back in February 1973, 15 years prior to his interview with Roberts, Irvin was sharing similar sentiments after being chosen by the Special Committee on the Negro Leagues to become a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame,

“I wasted my best in the Negro Leagues,” Irvin said. “I’m philosophical about it. There’s no point in being bitter. You’re not happy with the way things happen, but why make yourself sick inside? There were many guys who could really play who never got a chance at all.”

Though he didn’t beat Robinson to the big leagues as a player, Irvin, with his reputation for diplomacy, in August 1968 became the first Black man to be named to an executive position in professional baseball headquarters when he was named assistant director of promotion and public relations, a new position in the office of Commissioner William D. “Spike” Eckert.

In announcing the appointment, Eckert said of Irvin, who had worked on the public relations staff of the Rheingold Brewery as well as a scout and instructor for the New York Mets since leaving the game as an active player: “He was selected after considerable review of the abilities needed for this job and he has the best qualifications of anyone we considered. I’m delighted Monte is joining us.”

Irvin would remain a trusted member of the MLB commissioner’s staff until Bowie Kuhn, Eckert’s successor, left office in 1984.

Irvin turns 96 years old on February 25.

Bill Francis is a Library Associate at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum