“Hank Greenberg has won the admiration of military men and civilians with the splendid attitude he has shown since joining the Army.”

- Home

- Our Stories

- Notes from Hank

Notes from Hank

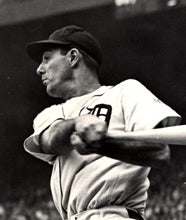

Hank Greenberg’s baseball career made him a legend. But it was his military service that cemented his place as an American hero.

Today – thanks to a unique currency donation – the two intersect in Cooperstown.

Greenberg, who smashed 331 home runs and won two Most Valuable Player Awards during what amounted to nine full seasons with the Tigers and the Pirates, served in the Army prior to the start of the United States’ formal involvement in World War II.

Immediately following the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, Greenberg re-enlisted – having been honorably discharged just two days prior to the attack.

By the time he returned to the Tigers midway through the 1945 season, Greenberg had bravely served his country at home and overseas – sacrificing about four-and-a-half prime seasons of his career. But even in wartime and away from the National Pastime, soldiers found ways to have fun.

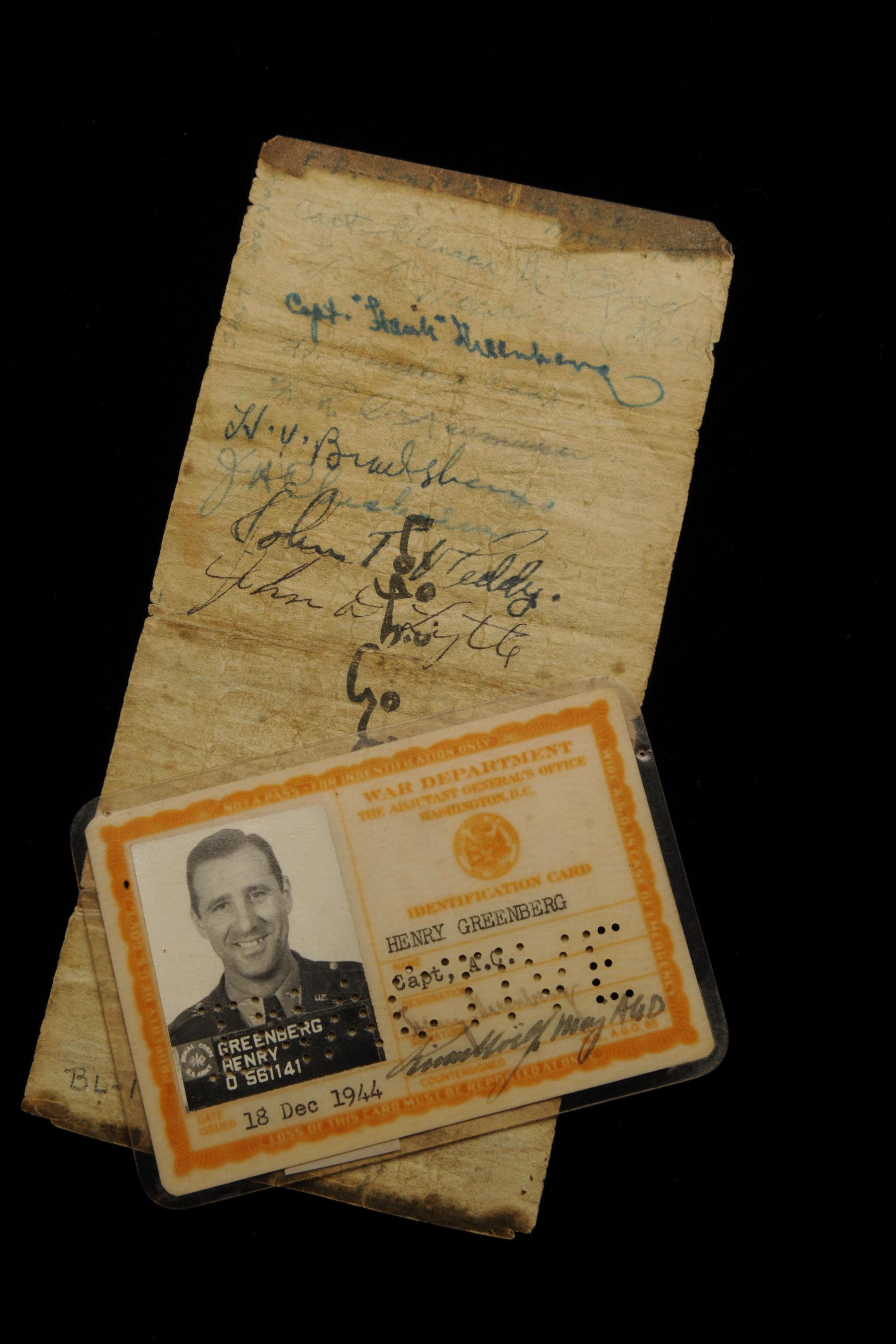

One military tradition – known as the “short snorter” – forever captures Greenberg’s heroism and his buddies’ camaraderie in a single artifact at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

In the Army now

The morning of May 7, 1941, Hank Greenberg submitted to his induction in the United States Army. Inside a downtown Detroit industrial building that manufactured women’s corsets, he filled out forms, answered questions, and provided his fingerprints. The newsreel cameras rolled, photographers snapped pictures and a 13-piece WPA orchestra played swing music, considered good for morale. The day before, Greenberg had hit two home runs –perhaps the last of his career – and powered the home team to victory over the Yankees.

That morning marked the culmination of 10 weeks of controversy dating back to February when a member of Draft Board No. 23 leaked Greenberg’s private request for Class 2 classification “because my years of earning power are limited and one year out of action will reduce my effectiveness considerably.”

If granted, the 30-year-old Greenberg would at least be allowed to finish the 1941 season and might avoid military service altogether. He had been baseball’s highest-paid player in 1940 and expected a raise after earning MVP honors. The national press jumped on the story, which stirred debate on a hero’s obligations, even before America had entered the war.

John Considine of the Washington Post thought it reasonable that Greenberg be asked to give up his income for a single season rather than potentially missing two earning years during his prime. On the other side, John Kieran of The New York Times argued that ballplayers like Greenberg had an elevated responsibility as “heroes to the boys of the land” not only to serve but they should be “lifted above the common citizenry.”

In what was to be a routine physical examination, the doctor found Greenberg in perfect health except for second degree bilateral pens planus, or two flat feet. The diagnosis relegated him to class 1-B, qualifying him only for limited detail. Hank’s flat feet were no surprise – they had troubled him since his youth – but the doctor’s diagnosis was met with incredulity. Wait a minute, the guy can run the bases, but he’s not fit to march in rank?!

Not wanting to be accused of favoritism, the members of Draft Board 23 sought a second opinion from a Detroit physician, who, not surprisingly, recommended that Hank be reclassified 1-A.

Once again, his situation divided public opinion and drew out the bigots like the one who wrote to him: “If you dare to play baseball this year with your poor flat feet and your big Jewish nose, you will be America’s No. 1 slacker.”

But Greenberg submitted when summoned to service.

Life, the most popular magazine in the country, ran a three-page spread on Greenberg’s eventual induction, documenting the metamorphosis of the player known as “Hankus Pankus” into Private Greenberg. George Martin gushed in the Minneapolis Tribune: “Hank Greenberg has won the admiration of military men and civilians with the splendid attitude he has shown since joining the Army.” Senator Joshua Bailey of North Carolina praised Greenberg for his sacrifice, giving up his $55,000 baseball salary for $21 a month in Army pay. “To my mind, he’s a bigger hero than when he was knocking home runs,” Sen. Bailey told The New York Times. Regarding the controversy that surrounded his draft status, the Detroit Jewish Chronicle concluded, “Hank emerges as patriotic as any of those who criticized him.”

Hank was officially assigned to C Company, 2nd Infantry, 5th Division, an anti-tank unit housed among the clapboard buildings of Fort Custer, about 125 miles west of Detroit. In his first six months, his company commander promoted him three times, to first class private, then corporal and finally sergeant. He was in charge of a five-man crew and responsible for the care of the Army’s 37-millimeter anti-tank guns.

On December 5, the United States Army released Hank Greenberg from active duty. After seven months in the service, he was eager to return to the Tigers.

Two days later, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor.

Back for More

Greenberg was the first major leaguer to re-enlist. “We are in trouble, and there’s only one thing to do – return to the service,” he said. Rather than wait for the call as a member of the reserves, he went to Washington, D. C., and enlisted in the Army Air Forces. “This doubtless means I am finished with baseball, and it would be silly for me to say I do not leave it without a pang,” Hank said. “But all of us are confronted with a terrible task – the defense of our country and the fight of our lives.”

“Fans of America, and all baseball, salute him for that decision.”

The Sporting News praised Greenberg for his willingness to protect the ideals of American democracy that had allowed the son of Romanian immigrants to achieve success. Editor J.G. Taylor Spink credited Hugh Mulcahy for being the first major league ballplayer drafted while the country was still neutral and Bob Feller for being the first to enlist after the declaration of war, “But the decision announced last week by Hank Greenberg gave the game and the nation a special thrill,” Spink wrote. He noted that Hank could have stayed home, said he had already done his bit, but he decided to serve again. “Fans of America, and all baseball, salute him for that decision.”

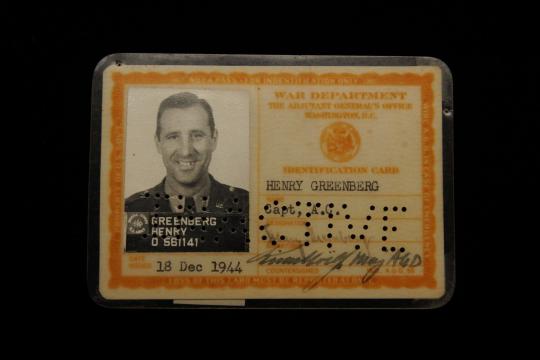

After completing a course at the Officers Candidate School in Miami Beach later that spring, Greenberg was commissioned a second lieutenant and assigned to the Headquarters Flying Training Command in Fort Worth, Texas. There, he supervised the base’s athletic program and traveled around the country inspecting training facilities. He was promoted to first lieutenant in November and four months later, in light of his “superior” performance, was promoted again to captain.

After 16 months at Fort Worth while the war dragged on, Hank requested duty closer to the action. In early 1944, Captain Greenberg shipped out to the China-Burma-India theatre with the first group of B-29s employed overseas. The United States planned to bring down the Japanese on the backs of these planes. The 58th Bombardment Wing, with Hank as its commanding officer, set up a base in China’s south-central province of Szechuan.

On the inaugural mission, one of the B-29s failed to clear the runway and burst into flames. Hank and a chaplain bravely dashed out of the control tower toward the wreck. When they were maybe 50 yards away, the plane’s bomb load began exploding and knocked them off their feet. They got up and continued toward the plane. They were surprised to find five crew members who had managed to climb from the wreckage. “Some of them were pretty well banged up, but no one was killed,” Hank said. “That was an occasion, I can assure you, when I didn’t wonder whether or not I’d be able to return to baseball.”

Written History

In February 1944 during a flight on the way to China, Greenberg met Lt. Col. Edward Smith in a plane over the Atlantic Ocean.

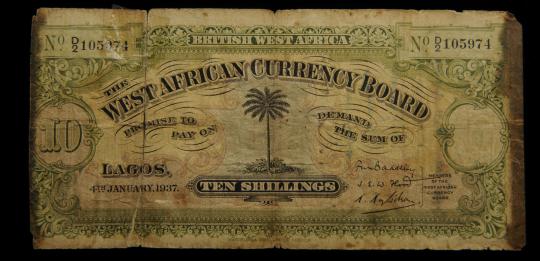

After striking up a conversation, Smith asked Greenberg to sign 10 shilling note from British West Africa (now Nigeria). Tradition dictated that if you were caught in an Officer’s Club without your short snorter – a bill signed by another officer – you had to buy everyone a round of drinks. But if you had yours, the challenger bought your next drink.

Smith never lost his – and later donated the bill with the famous autograph to the Museum’s collection.

Just 12 years after his meeting with Edward Smith, Greenberg would be enshrined in Cooperstown.

Coming Home

When Hank returned to the United States in October 1944, he received the Presidential Unit Citation and four bronze battle stars.

Assigned to the Air Technical Service Command’s production division based in Manhattan, he assumed the role of cheerleader, motivating workers at war plants lagging in production. “I never talk about baseball,” he told a reporter. “War’s my business now, and so I talk war, stressing the dire need for greater effort.”

On May 7, 1945 – exactly four years after Greenberg’s initial induction – German troops surrendered to the Allies. With the war in Europe over, the Armed Services no longer needed all of its officers. The Army Air Forces placed Capt. Greenberg on the inactive list, and on June 14, 1945, he walked out of Fort Dix willing – if not ready – to return to the Tigers, who held a slim half-game lead over the Yankees.

A little more than two weeks later, Greenberg homered in his first game back – on July 1, 1945 against the Athletics – proving that America was ready and able to return from war. For Greenberg, it was another historic moment in a lifetime filled with them.

John Rosengren is the author of Hank Greenberg: The Hero of Heroes. This article is adapted from that book.