“Of all the legendary moments in a legendary career, it just might be the most profound. It really gets to the essence of his larger-than-life persona.”

- Home

- Our Stories

- He Called It

He Called It

Michael Gibbons chuckles when he thinks about his rec league softball days and those occasions when hitters stepped to the plate and pointed fingers or bats at center field fences before pitches were delivered.

“No one needed to explain what was going on,’’ says Gibbons, the longtime executive director of the Babe Ruth Birthplace & Museum in Baltimore. “Everyone knew the batters were mimicking the Babe’s ‘Called Shot.’ ”

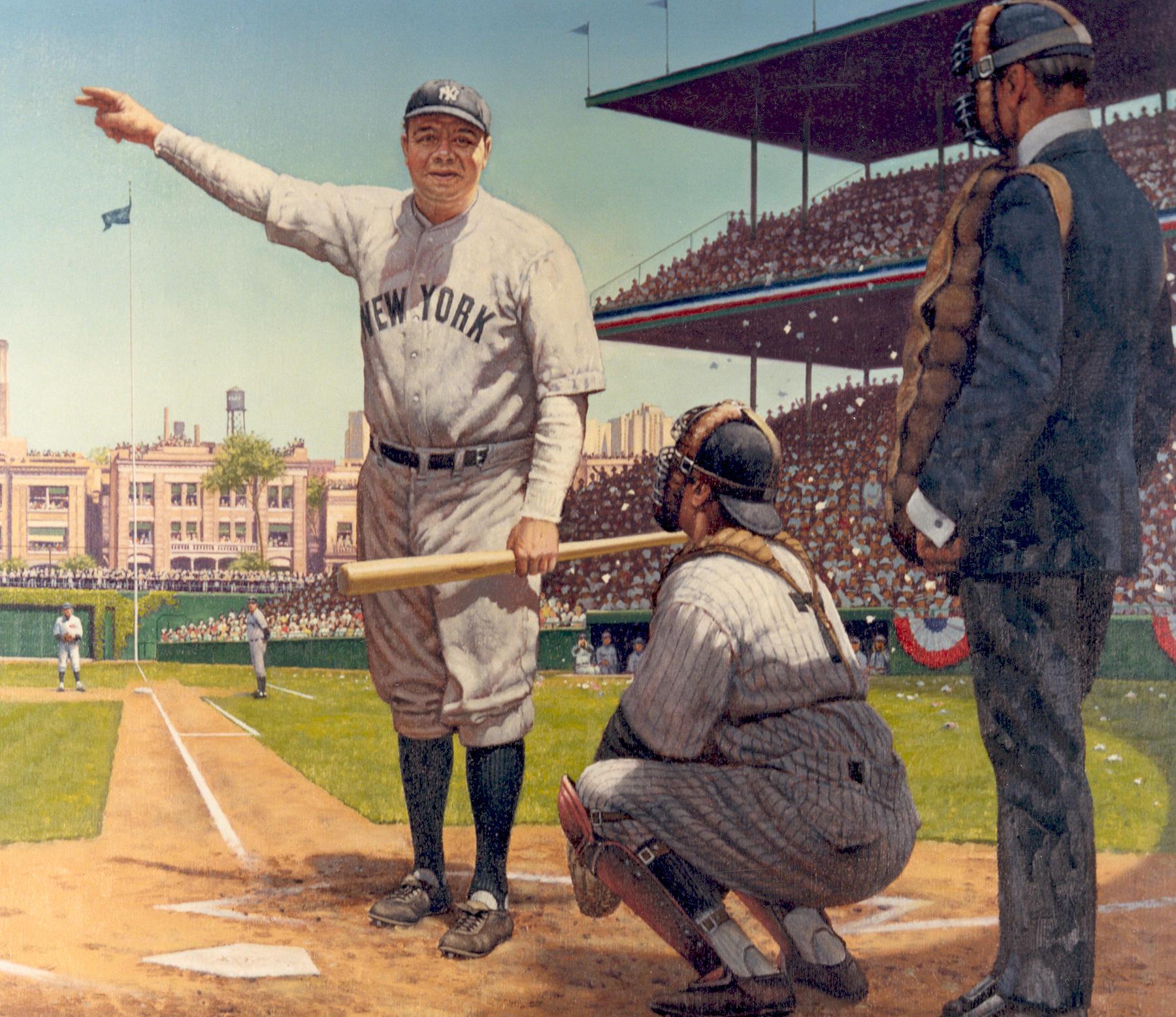

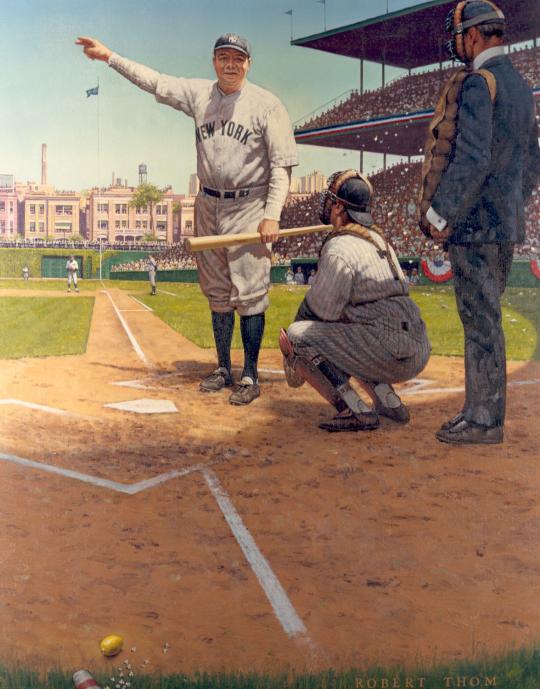

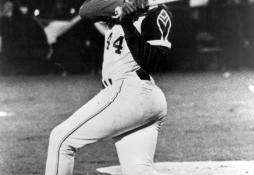

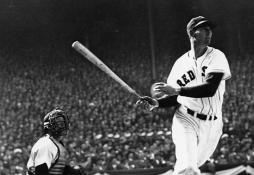

Almost 100 years after Ruth’s famous home run in the 1932 World Series, amateur sluggers around the world are still imitating one of the most memorable moments in baseball and sports history. And people still are debating whether the Sultan of Swat actually guaranteed he would hit a home run into the center field bleachers at Chicago’s Wrigley Field during his Game 3, fifth inning at-bat that first day of October. Or whether this merely was an apocryphal tale spun by an overly creative sportswriter, who, with Ruth’s blessing, wasn’t about to let the facts get in the way of a great story.

“It certainly is one of the cornerstones of his legacy,’’ says Gibbons, whose office is one floor above the room in which Ruth was born. “Of all the legendary moments in a legendary career, it just might be the most profound. It really gets to the essence of his larger-than-life persona.”

That persona resulted in election to the Hall of Fame in the inaugural Class of 1936.

Gibbons has read and heard all the interviews with Ruth and the players and fans in attendance at Wrigley that day. He has closely examined still photographs and the two 16mm home movies shot from the stands in those pre-television days. His conclusion? The New York Yankees slugger probably predicted he was going to do something with that pitch, but most likely didn’t indicate that he was going to smash it into the center field bleachers more than 440 feet away.

“You can see in the films that he’s pretty demonstrative and he’s jawing with (pitcher) Charlie Root and the Cubs players who are riding him pretty good from the third base dugout,’’ Gibbons says. “But it looks to me like he’s pointing at Root and the Cubs bench jockeys. For all we know, he might have been telling Root that he was going to take his head off. I really don’t see the Babe pointing to the center field bleachers. But that’s where he hit the ball and everything that followed became part of baseball lore.”

The vitriol from Cubs players and many of the 49,986 fans crammed into Wrigley that day was ignited by some newspaper comments the Babe made before the Series even began. One of Ruth’s former teammates, Mark Koenig, had joined the Cubs in late August that season and batted .353 in 33 games to help propel Chicago to the National League pennant. Although Koenig had been a catalyst, his teammates felt he was deserving of just a half-World Series share because he had been with the team for such a short time. When Ruth heard that Koenig wasn’t voted a full share, he lambasted the Cubs in a story published in the Chicago Daily Tribune. “Sure, I’m on ’em; I hope we beat ’em four straight,’’ he was quoted as saying. “They gave Koenig a sour deal in their player cut. They’re chiselers and I’ll tell ’em so.”

Not surprisingly, Ruth’s comments did not set well with Cubs players or fans. After winning the first two games of the Series in the Bronx, the Yankees arrived in Chicago by train. “Apparently, when they got off to go to the hotel, they were greeted by a bunch of angry Cubs fans, who began spitting at Babe and his wife, Claire, ’’ Gibbons says. “She actually got the worst of it, and Babe was not pleased. By the time Game 3 commenced, the atmosphere in Wrigley was super-charged, almost riotous. The fans and the Cubs were very angry about Ruth’s comments, and the Babe was very angry about the treatment he and his wife received. He was determined to make them pay.”

The first two Yankee batters reached base in Game 3, and Ruth was greeted with thunderous boos when he stepped to the plate in the top of the first. Some fans reportedly hurled rotten fruit, as well as verbal abuse, at him. Ruth responded by smacking a three-run homer.

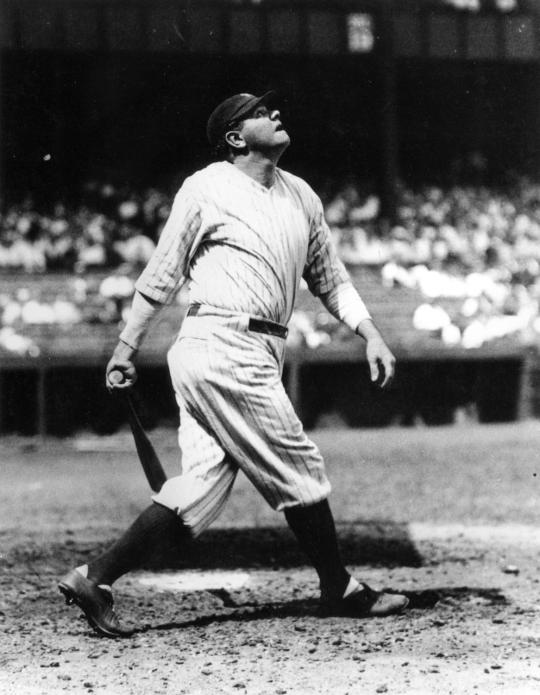

Chicago battled back to knot the score at 4, and when Babe came to bat in the top of the fifth he was serenaded with more boos and cat-calls from the fans and the Cubs players. Two movies – one shot by Matt Miller Kandle Sr. that first surfaced in the 1970s and another taken by Harold Warp that came to light in the 1990s – show an animated Ruth. After taking strike one, he holds up his hand and appears to be pointing at either Root or the Cubs bench. Following another called strike, he repeats the gesture. “Because of the camera angles of the two films – one from the vantage point of home plate and the other, slightly off to the third base side – it’s hard to be definitive,’’ Gibbons says. “But it doesn’t look to me like he’s pointing to centerfield. He’s definitely talkative and he appears through his pointing and body language to be letting the Cubs know that something is going to happen with the next pitch.”

“All of us players could see it was a helluva good story. So we just made an agreement not to bother straightening out the facts.”

Root then throws a curve ball, low and away from the left-handed hitting Ruth, who appears to be crowding the plate. The Bambino goes down and gets the pitch and whacks a line drive homer to centerfield near the flag pole. Some reports have the ball traveling 490 feet. As Ruth rounds first, he makes a wave-off gesture toward the Cubs dugout. And as he approaches third base, he makes a two-armed push motion toward their bench. Upon touching home plate, he no longer can suppress his joy and begins smiling ear-to-ear. Root stays in the game for one more pitch, which Lou Gehrig hits out of the park. The Yankees win 7-5, then complete the sweep the next day with a 13-6 victory.

Some newspaper stories filed the day of Game 3 alluded to Ruth’s pointing, but only one story reported that he called his shot. “In the fifth, with the Cubs riding him unmercifully from the bench, Ruth pointed to center field and punched a screaming liner to a spot where no ball had been hit before,” wrote Joe Williams, a feisty, opinionated sports editor for Scripps-Howard, one of the nation’s largest newspaper chains. Before putting his story on the wire, Williams wrote a bold headline that invoked a billiards reference. It read: “Ruth Calls Shot As He Puts Home Run No. 2 In Side Pocket.” The story and headline received prominent play in the widely circulated New York World-Telegram. “Interestingly, in the ensuing days, other writers began following his lead and started reporting that the Babe had called his shot,’’ Gibbons says. “It kind of spread like wildfire after that.”

The story certainly seemed plausible because there had been precedent. Six years earlier, the Babe had promised a seriously ill child named Johnny Sylvester that he would hit a homer for him that Wednesday. Ruth wound up hitting three homers and Sylvester made a miraculous recovery.

Initially, Ruth said he was pointing to the Cubs bench to let them know he had one more strike, but once the story got some legs, the media-savvy slugger was happy to run with it. “It’s in the papers, isn’t it?’’ he said when asked about the tale’s veracity. In a voiceover to Movietone footage, Ruth told viewers: “Well, I looked out to center field and I pointed. I said, ‘I’m going to hit the next pitched ball right past the flag pole.’ Well, the good Lord must been with me.” In his 1947 autobiography, he embellished the story saying he actually dreamt about the homer the night before. Cubs first baseman Charlie Grimm, longtime Wrigley Field public address announcer Pat Pieper and Gehrig were among those who backed the Babe’s interpretation.

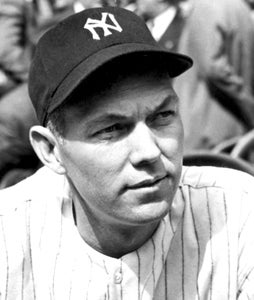

But others, including Root and two of Ruth’s teammates – Bill Dickey and Frank Crosetti – said the story was fabricated. “All of us players could see it was a helluva good story,’’ Dickey told venerable Washington Post columnist Shirley Povich in a 1988 interview. “So we just made an agreement not to bother straightening out the facts.”

In 1992, the Babe Ruth Museum ran a year-long exhibit about the “Called Shot” and asked fans to vote if they believed the story or not. Eighty-five percent said they did. “People want to believe it, and that’s part of the beauty of the game of baseball and the legend of Babe Ruth,’’ Gibbons says. “No other game lends itself more to myth and legacy and debate.”

The “Called Shot” lives on in popular American culture. There have been references in feature films (The Natural, The Sandlot, and Major League), beer commercials (Bud Light), books (comedian George Carlin’s memoir, Napalm and Silly Putty) and television shows (The Simpsons). And athletes in all sports continue to follow Ruth’s lead and make bold guarantees.

“I think it’s great,’’ says Gibbons. “Babe Ruth and his ‘Called Shot’ are very much alive.”

Scott Pitoniak is a Rochester, N.Y.-based freelance writer