- Home

- Our Stories

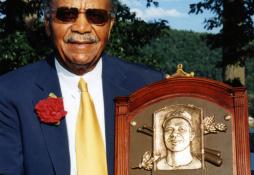

- #Shortstops: Art Pennington: An Equal among Greats

#Shortstops: Art Pennington: An Equal among Greats

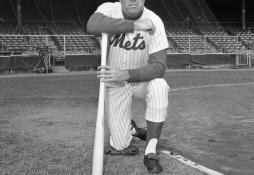

In the photograph, four players stand together; two are enshrined in the Hall of Fame as among the greatest ever -- and another is an All-Star and MVP -- African Americans who were pioneers in the integration of baseball. Larry Doby stands in profile at the left. Don Newcombe has his head down, his hand up to his face, recognizable by his broad hips and barrel chest and the Brooklyn “B” on his cap. Roy Campanella is holding court, caught in mid-sentence, eyebrows raised, a baseball in his hand.

Then there is the man to the far right, an unfamiliar face. He stands, glove-hand on hip, a big man, thick, strong. His jersey has “Chicago” stitched across the front, but the sleeve insignia is neither White Sox nor Cubs. Who is this?

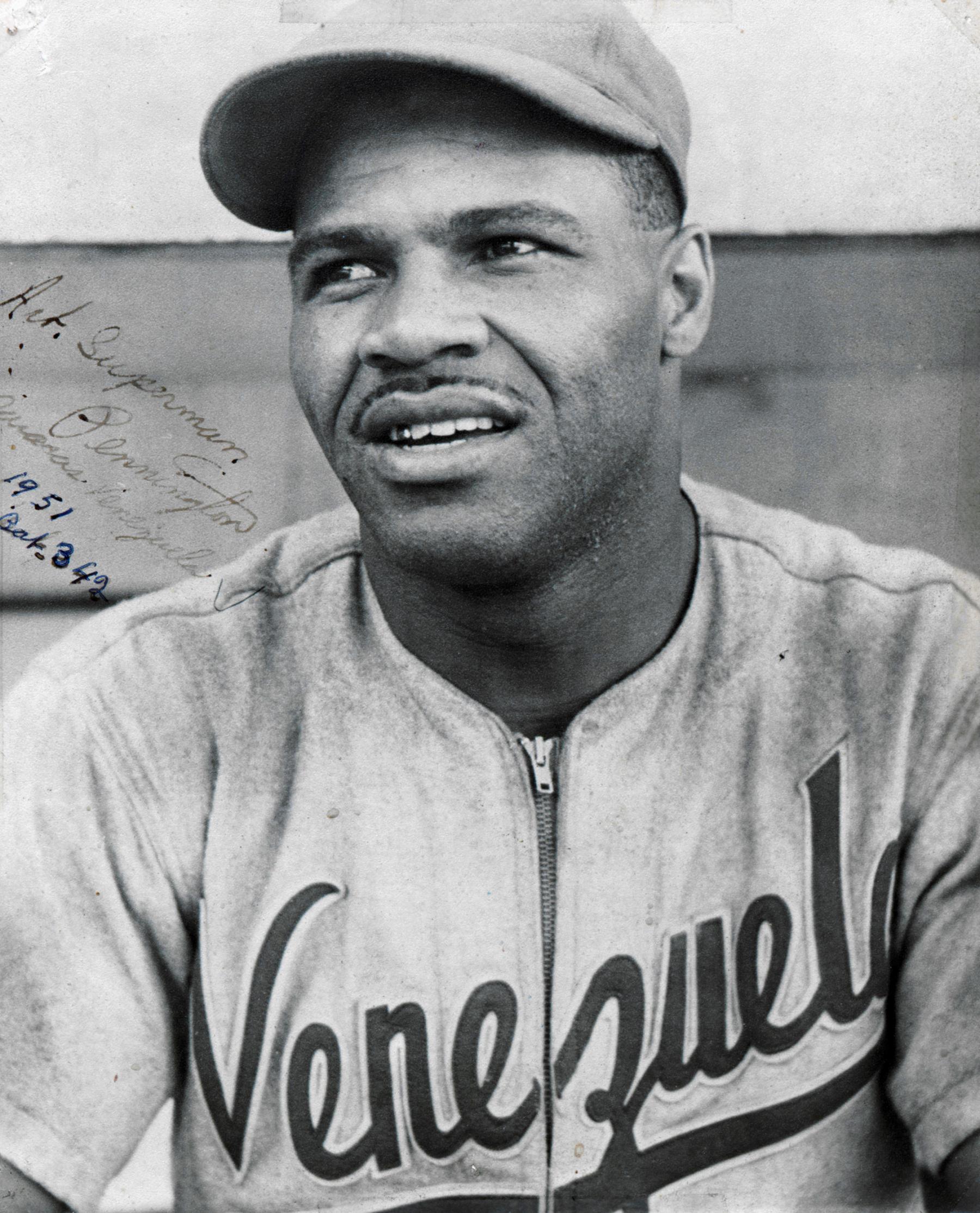

“Art D. Pennington. They called me the Superman,” he once said by way of introduction. “That’s what they called me all my life. They knew I could play. I could run like a deer, and I could throw that ball outta sight.”

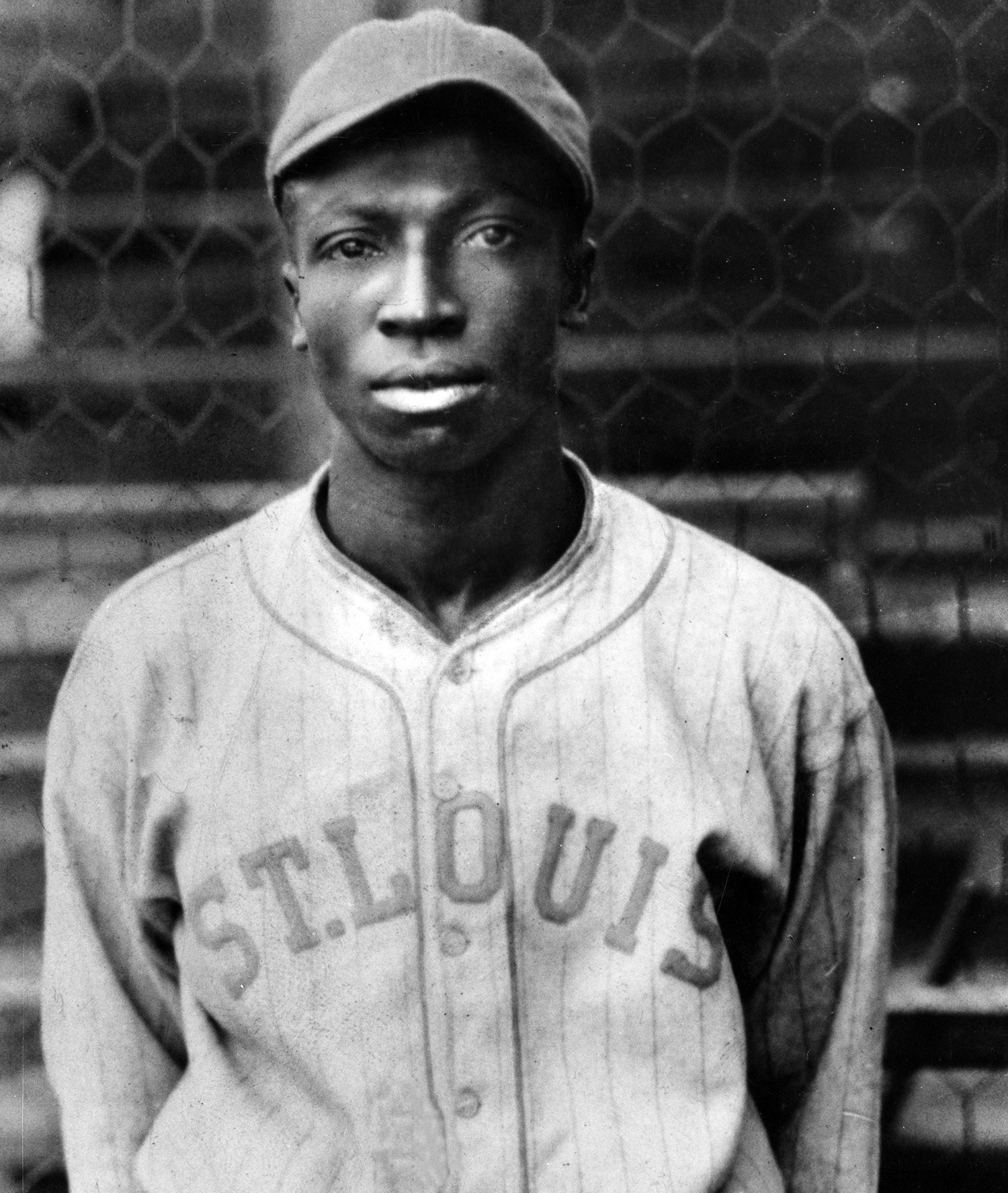

Born in Memphis, Tenn., in 1923, Pennington played professional baseball for 20 years, in the Negro Leagues, the Mexican League, in Venezuela and Cuba, and the integrated minor leagues. He was a switch hitter, and played every position except catcher (“It’s bad on your fingers”).

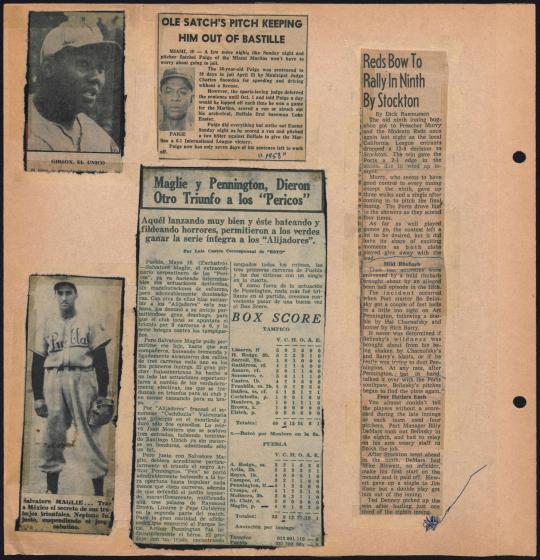

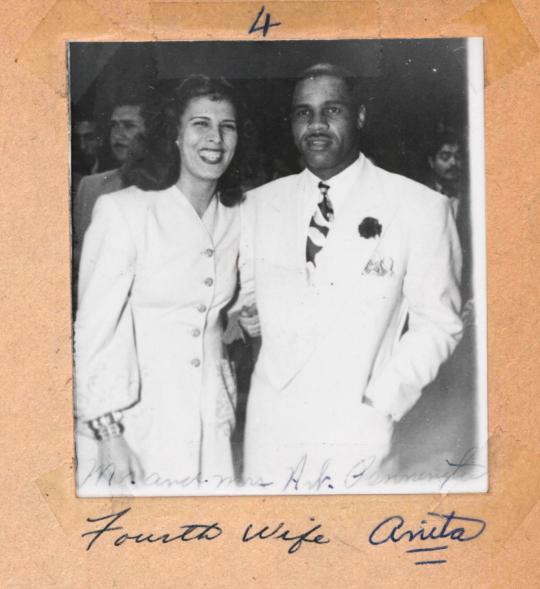

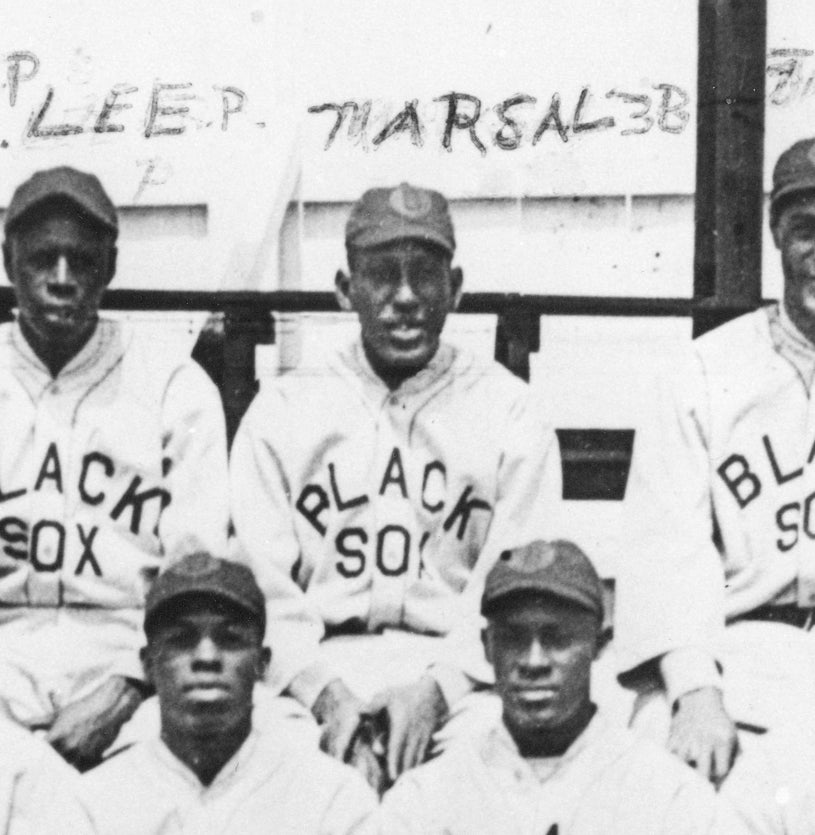

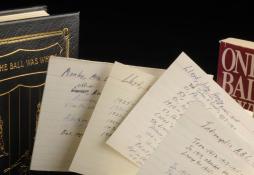

His remarkable career is chronicled in a scrapbook recently digitized as part of the Digital Archives Project at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Compiled by Pennington himself, it is an eclectic mix of photographs and clipped newspaper articles, yellowed with age, some in English and some in Spanish, in no discernible order. There are team photos; shots of him in action; photos of teammates; a photo of Josh Gibson; and personal photos, too: Pennington standing in a park in a suit, Pennington’s children blowing out candles on their birthday cakes; a page with one photo from each of his five marriages.

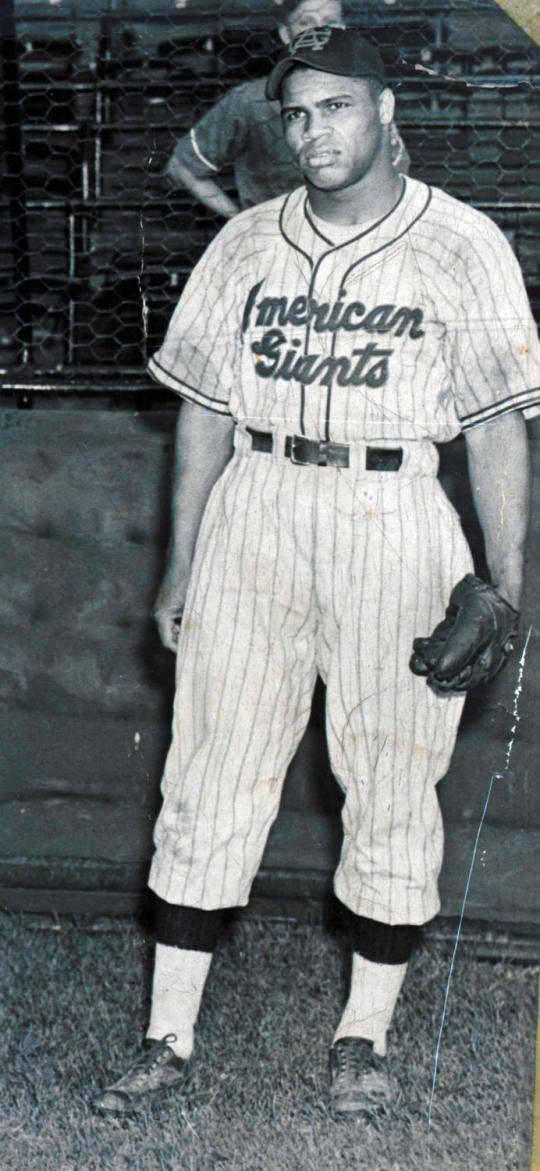

He started playing baseball professionally while he was still in his mid-teens, for the Zulu Clowns, a barnstorming team that played in painted faces and grass skirts and with slapstick antics. In 1941, just before his 18th birthday, he was signed by the Chicago American Giants of the Negro American League. He earned $125 a month, which he would give to his family: “We was the richest people on the block.”

The first time he hit against Satchel Paige, Paige chirped to the teenager, “Come on up, little boy.”

“That made me awful mad,” Pennington recalled, “so I says, I told him, ‘Throw it and duck.’ Man, he threw three by me so fast I didn’t even see ‘em.” Paige “had a foot about that long,” Pennington continued, his hands about two feet apart. “An’ you know Satchel would put that foot up in the air an’ you lookin’ at his foot an’ he throw the ball by you.”

If he couldn’t hit Paige, he could hit everyone else, and “Throw it and duck” became Superman’s signature phrase, his walk-up song. Statistics from the Negro Leagues are spotty at best, but he made the All-Star team in 1942.

Drafted into the Army, he refused to fight for a country that denied him so many opportunities. “I told ‘em, I said, ‘I don’t want to go to the Army. What I got to fight for? I can’t eat in no place, can’t go no place. Why do I wanna fight? I don’t know nothin’ ‘bout no Japs. They ain’t did nothin’ to me.’” The American Giants’ owner pulled some strings and he went back to playing baseball.

In 1945, he became a superstar, batting .359, leading the league in doubles, stealing 18 bases. He played in the same league as Jackie Robinson, and though Pennington was younger, he bested Robinson in batting average and steals and tied him for second in home runs. Superman was selected to his second all-star game.

Still, there were elements of playing with the American Giants that were painful. Players on Negro League teams couldn’t sleep in most hotels, couldn’t eat in most restaurants, couldn’t swim in the local pools. And the antics during barnstorming tours weren’t too far from those of the Zulu Clowns, like watermelon eating contests that he called “just embarrassin’.”

In 1946, Jorge Pasquel and his brothers shook up the baseball world by offering players huge contracts to come to the Mexican League, which he wanted to build up to a major league level. Pasquel targeted the biggest names:Ted Williams, Stan Musial and Bob Feller. He had long lured Negro League players to the Mexican League, including Willie Wells, Ray Dandridge and Josh Gibson. In 1946, Pasquel signed Superman, giving him $1,000 a month (a $400 raise). Pennington soon realized that he could earn additional money by playing in the Cuban and Venezuelan winter leagues, bringing his annual income up to $12,000 a year.

But what he found in Mexico was more valuable than money.

"When I left the United States, I never had so much freedom in all my life because you could eat anywhere and they got the finest restaurants, the beautifulest women – all colors, don’t make no difference – and they’re crazy about athletes. They got dance halls and I used to love to dance. I just told my mother, I said, ‘Mom, you should see this country. It’s beautiful. Mexico City and Monterrey and Acapulco. Everybody swimmin’ together."

He excelled on the field in Mexico, playing most for the Pueblo Pericos (Parrots), hitting .300 with on-base percentage over .400 across three seasons. Newspaper clippings in the scrapbook show him sliding into third on triples and being welcomed by teammates at the plate after home runs. One headline called him the “Coloso del Bateo” – The Colossus of Batting.

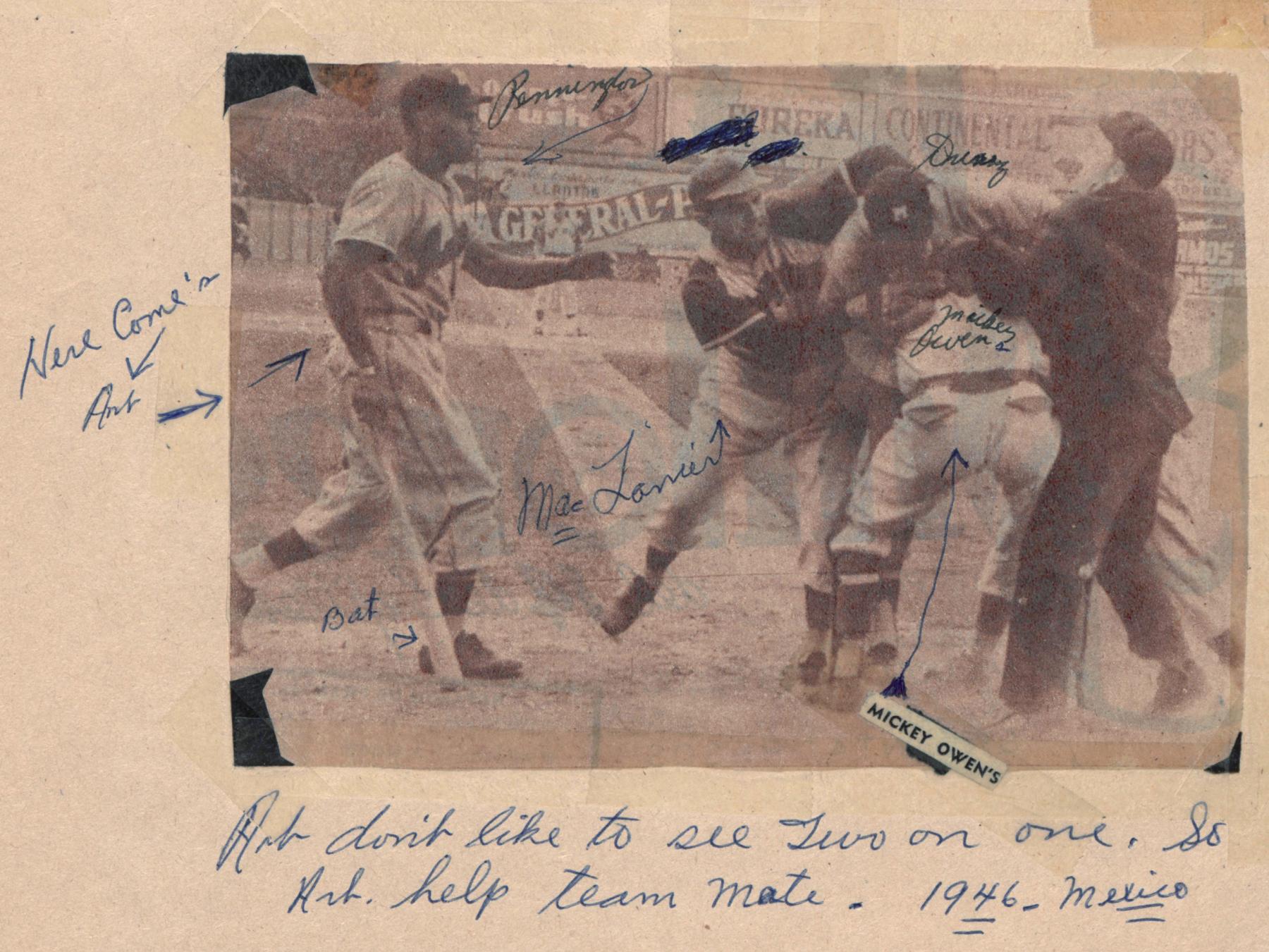

Pennington has annotated his scrapbook throughout. Under this photo clipped from a newspaper, Pennington's caption reads, “Art don't like to see two on one. So Art help team mate. 1946 - Mexico.” Arrows further identify Pennington, Max Lanier, Mickey Owens, and Claro Duany. Pennintgon has also pointed an arrow to “Bat” and “Here come's [sic] Art.” BA-SCR-2-025 (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

The quality of the Mexican League was impressive. Pennington was teammates with Cool Papa Bell, Double Duty Radcliffe and Sal Maglie. He played against Hall of Famers Leon Day, Ray Dandridge, Ray Brown, and Martin Dihigo, and big league All-Stars Max Lanier, Ace Adams, Mickey Owen, and Vern Stephens. “I just loved to play in them days,” he said, “I was young and I was full of spunk.”

While in Mexico, he met a Mexican woman named Anita, of Spanish decent, with white skin, red hair, and “movie star” looks. She became Pennington’s fourth wife, whom he stayed with until she died. In Mexico, they could go anywhere together without raising an eyebrow.

His mother, however, wanted Pennington to come home. By 1949, the Mexican League was suffering financially, and many players were heading back to the States, so Pennington, reluctantly, moved to Arkansas, where his parents lived. He ran into problems right away: He was told on the train ride home that he couldn’t sit with the white woman at his side. In the stations, they were forced into different segregated waiting rooms. Anita only spoke Spanish, and Pennington said, “I’m so glad she didn’t understand a lot of the stuff they was callin’ me.”

Life in America wasn’t easy. Though he quickly reached Triple-A with the Portland Beavers, he found the racism and segregation on the integrated team so oppressive that the next season, 1950, he returned to the Chicago American Giants, once again earning all-star honors.

He sometimes played in the minors, and sometimes down in Venezuela, where he was active in 1950 and 1951 and posted a .360 batting average. In the minors he put up Superman numbers, hitting .349 for the batting title in 1952 with the Keokuk Kernels and leading the league with 126 runs in 122 games. He hit .329 the next year, and .345 the next. As a 35-year old, he hit .339 for St. Petersburg, outhitting and outslugging Roger Maris. But he never was called up to the Major Leagues, something that he speculated was the result of having a white wife; interracial marriage was still illegal in the majority of states in the early 1950s. “I enjoyed it,” he said about his baseball career. “I did all right, so I don’t have no regrets. I don’t have no regrets at all.” Asked about not playing in the majors, he admits, “I was cheated, but I never think about it.”

Instead, he thinks about his days in Mexico. Where he lived as a free man, where he was treated as equal to his white fellow ballplayers, and treated as a hero by the fans. Where he could sit at any restaurant and go dancing in any club, and walk down the street, arm-in-arm with his wife.

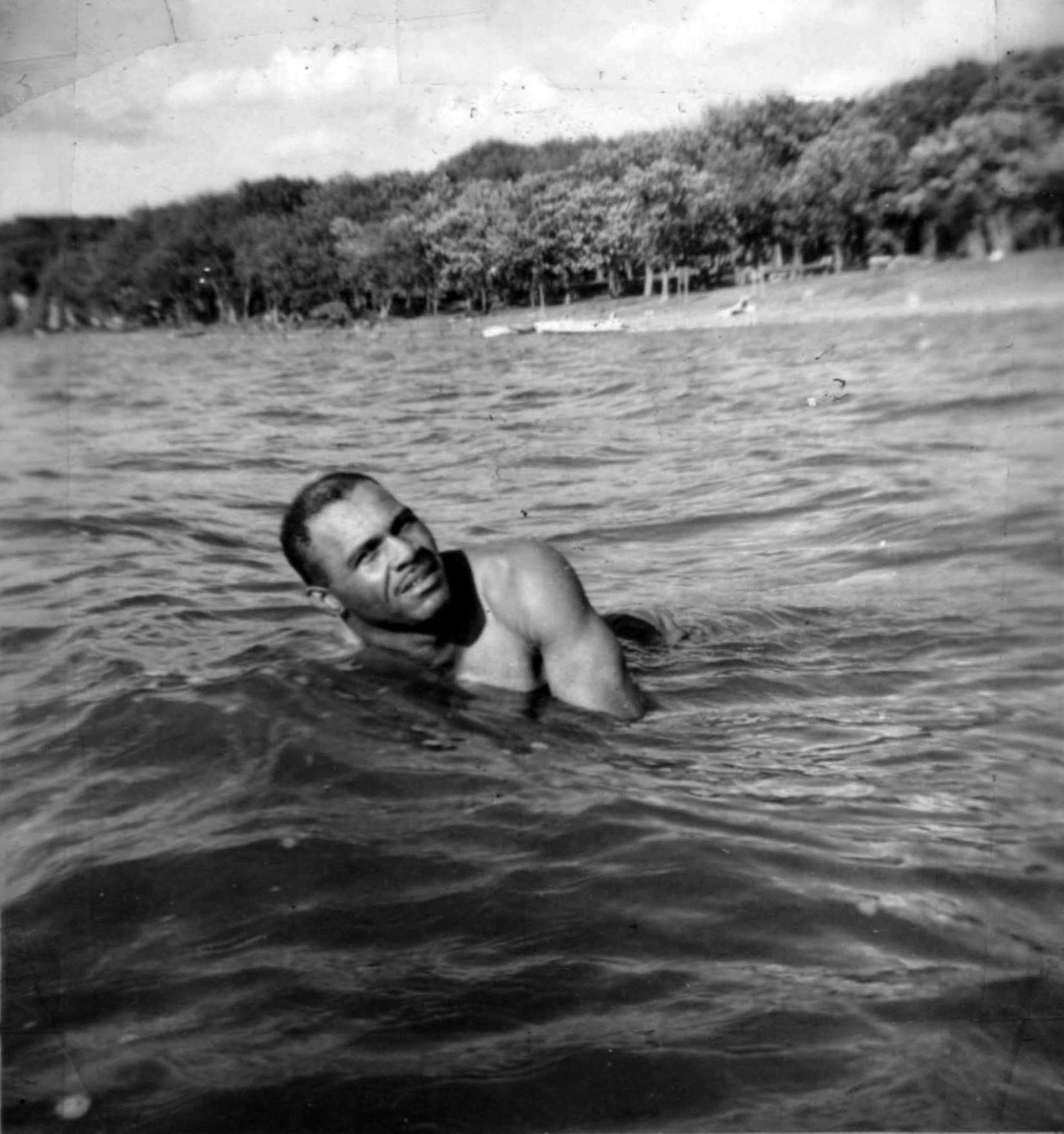

Near the back of the Art Pennington scrapbook, there is a small, square, black and white photo. Most of the image is of water, with a sliver of beach in the background. Just beyond the beach stands a thicket of trees, so leafy that the ground is lost in shadows. Above the branches, a sky is dotted with clouds. In the center of the image, near a small wave, with right shoulder submerged and left shoulder rising out of the water, bare and muscled, head angled to the surface, eyes directly on the camera, is Art Pennington, swimming.

Larry Brunt was a digital strategy intern in the Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program for Youth Leadership Development.