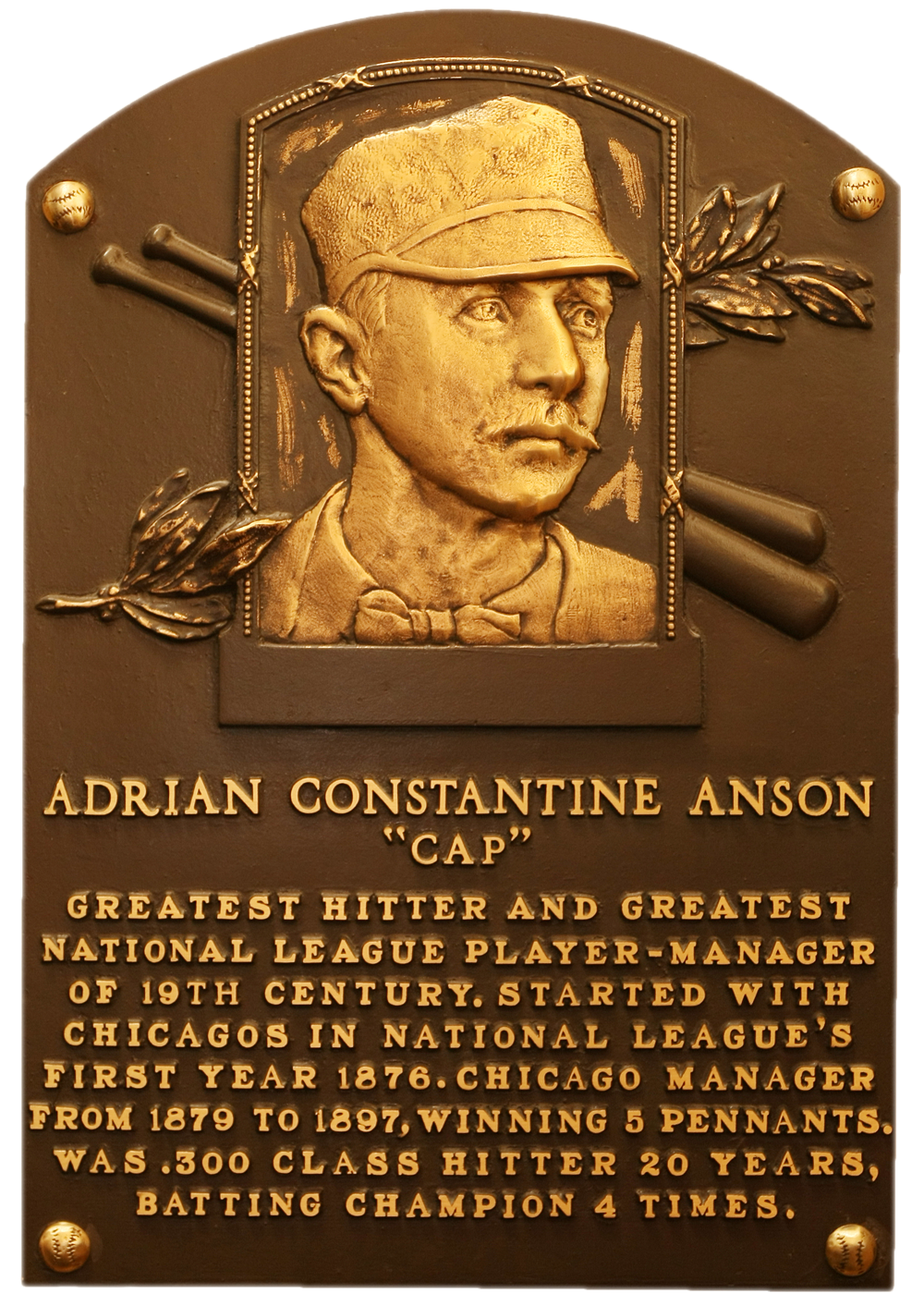

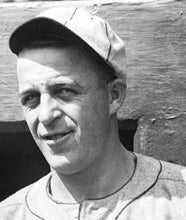

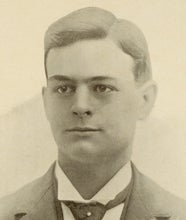

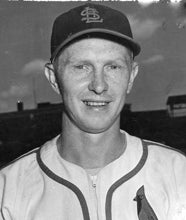

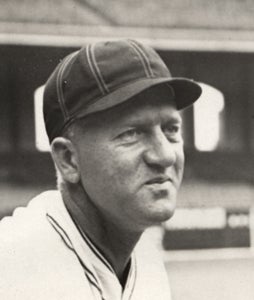

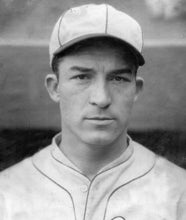

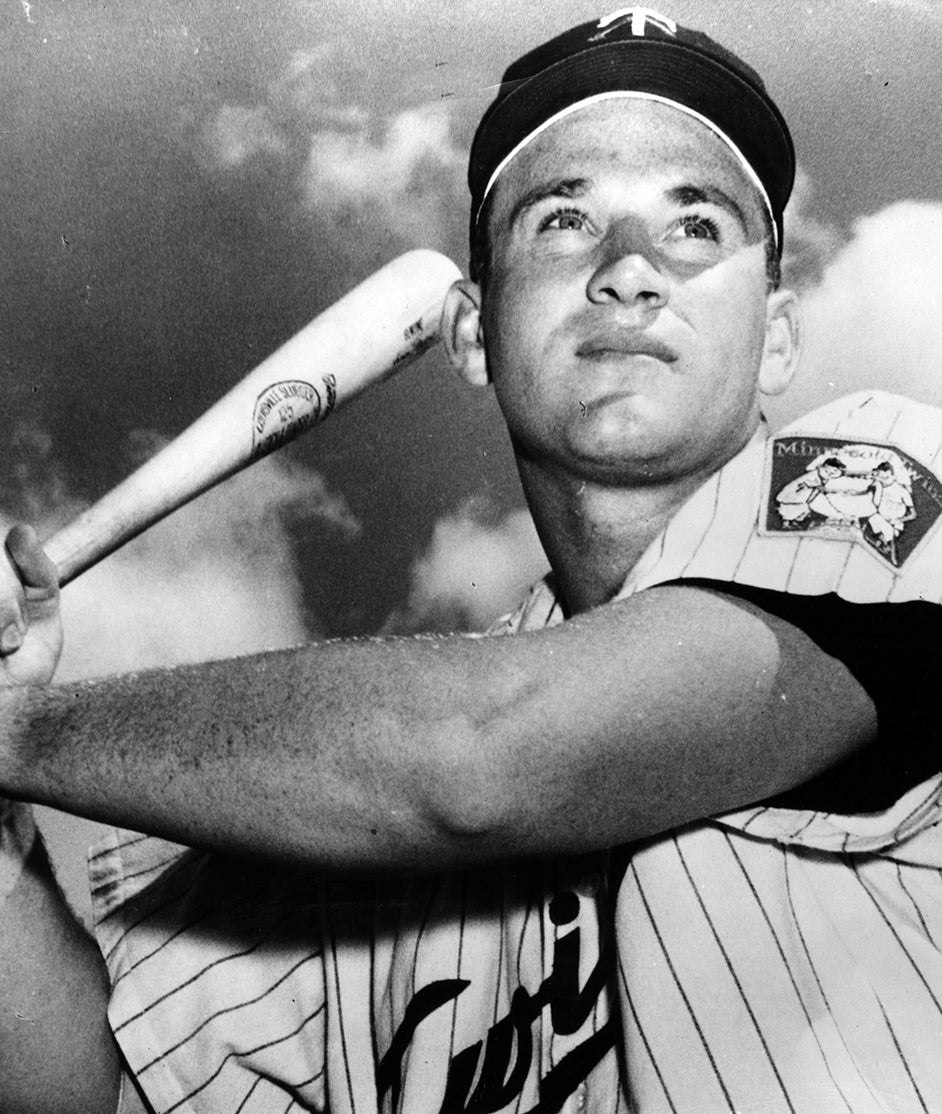

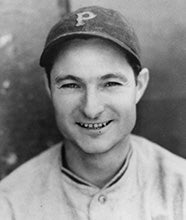

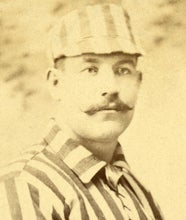

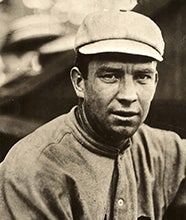

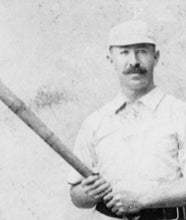

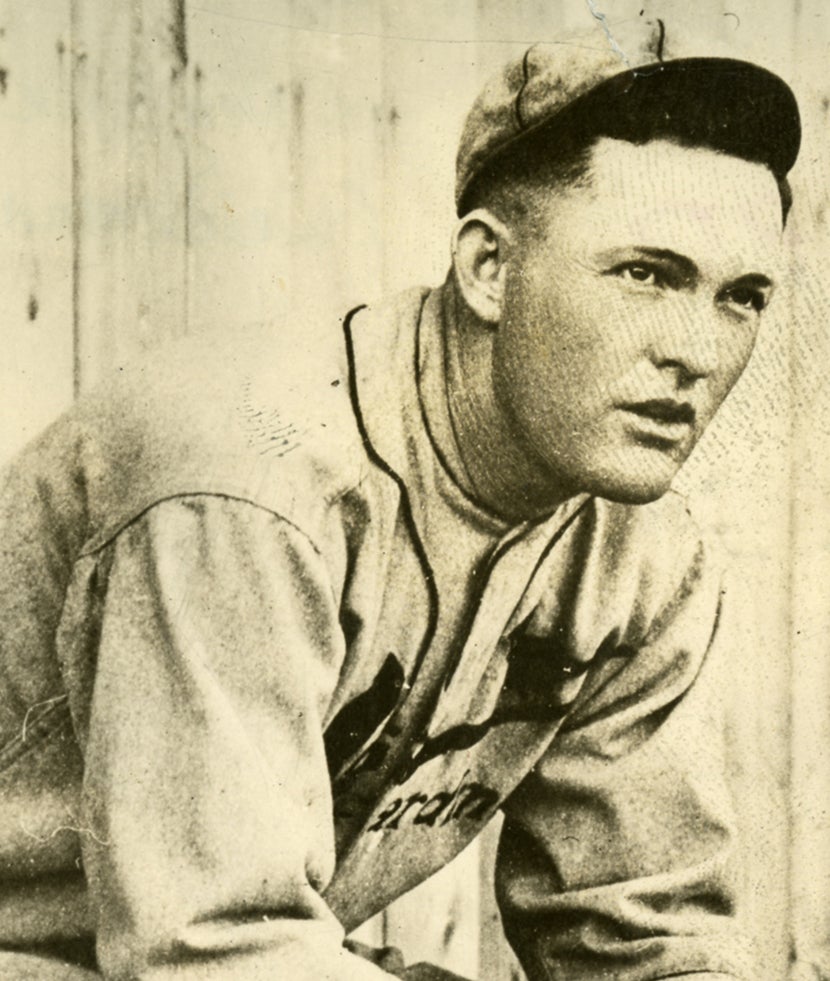

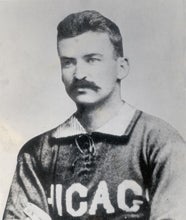

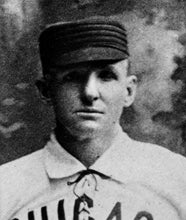

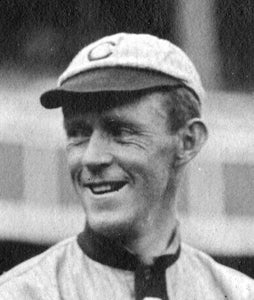

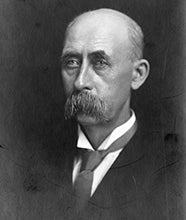

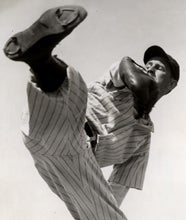

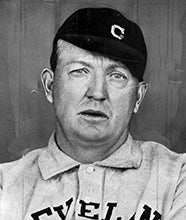

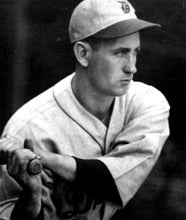

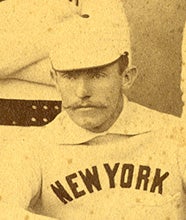

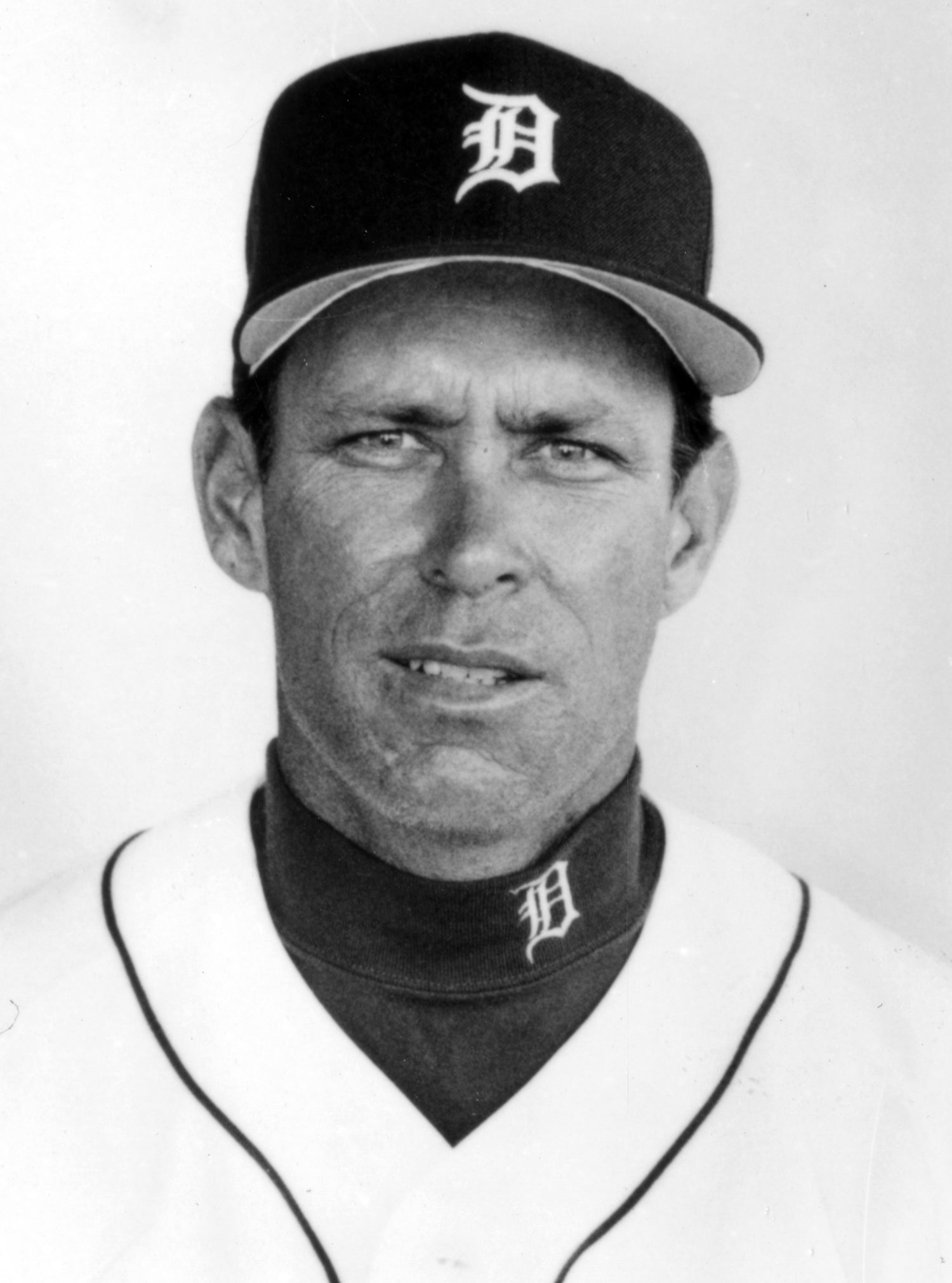

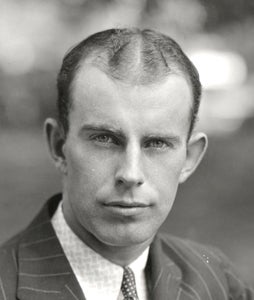

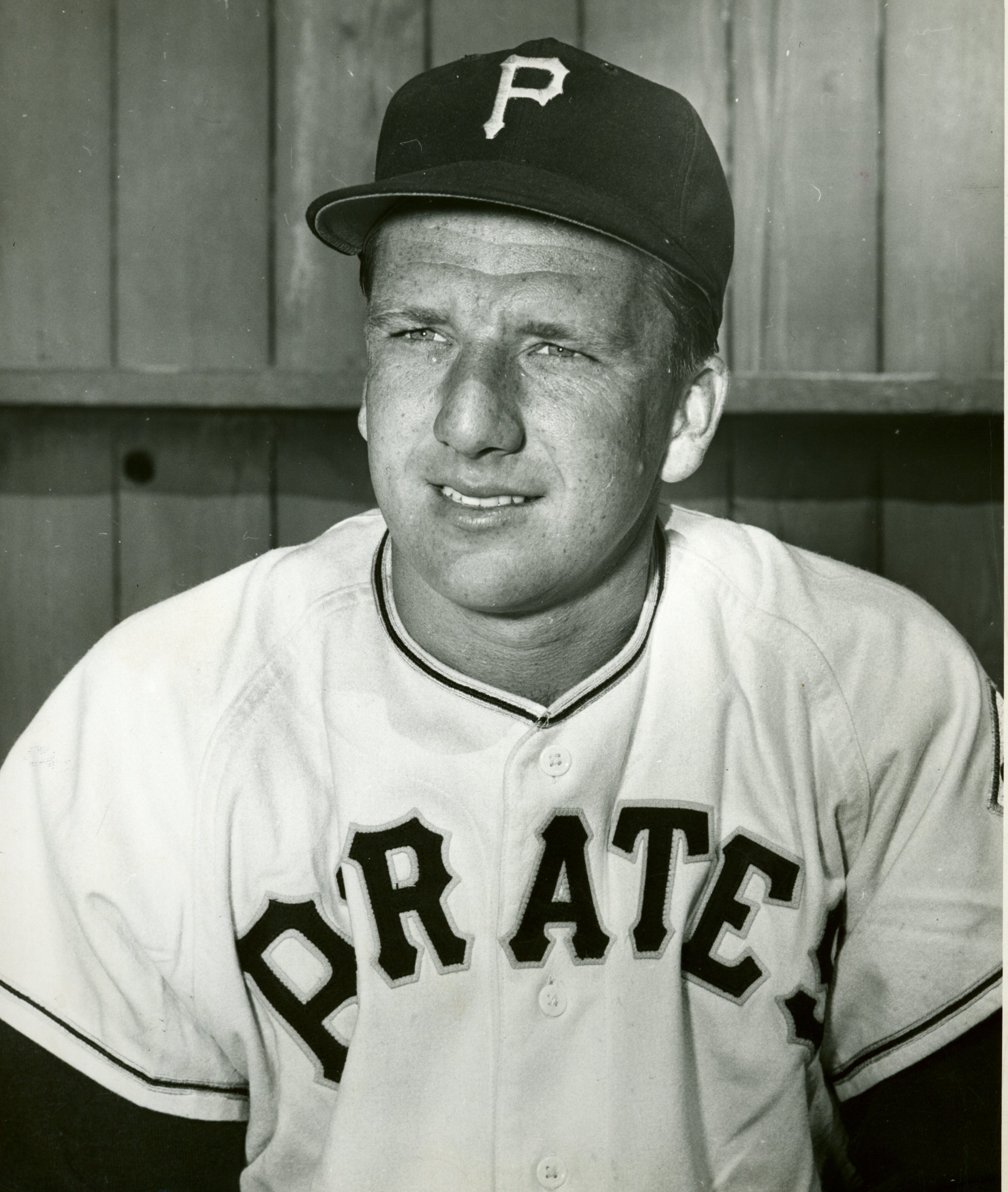

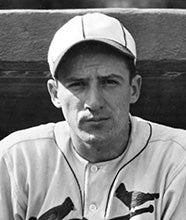

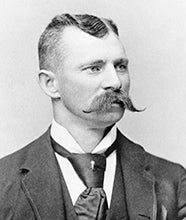

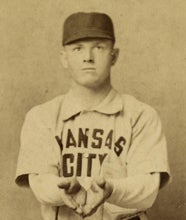

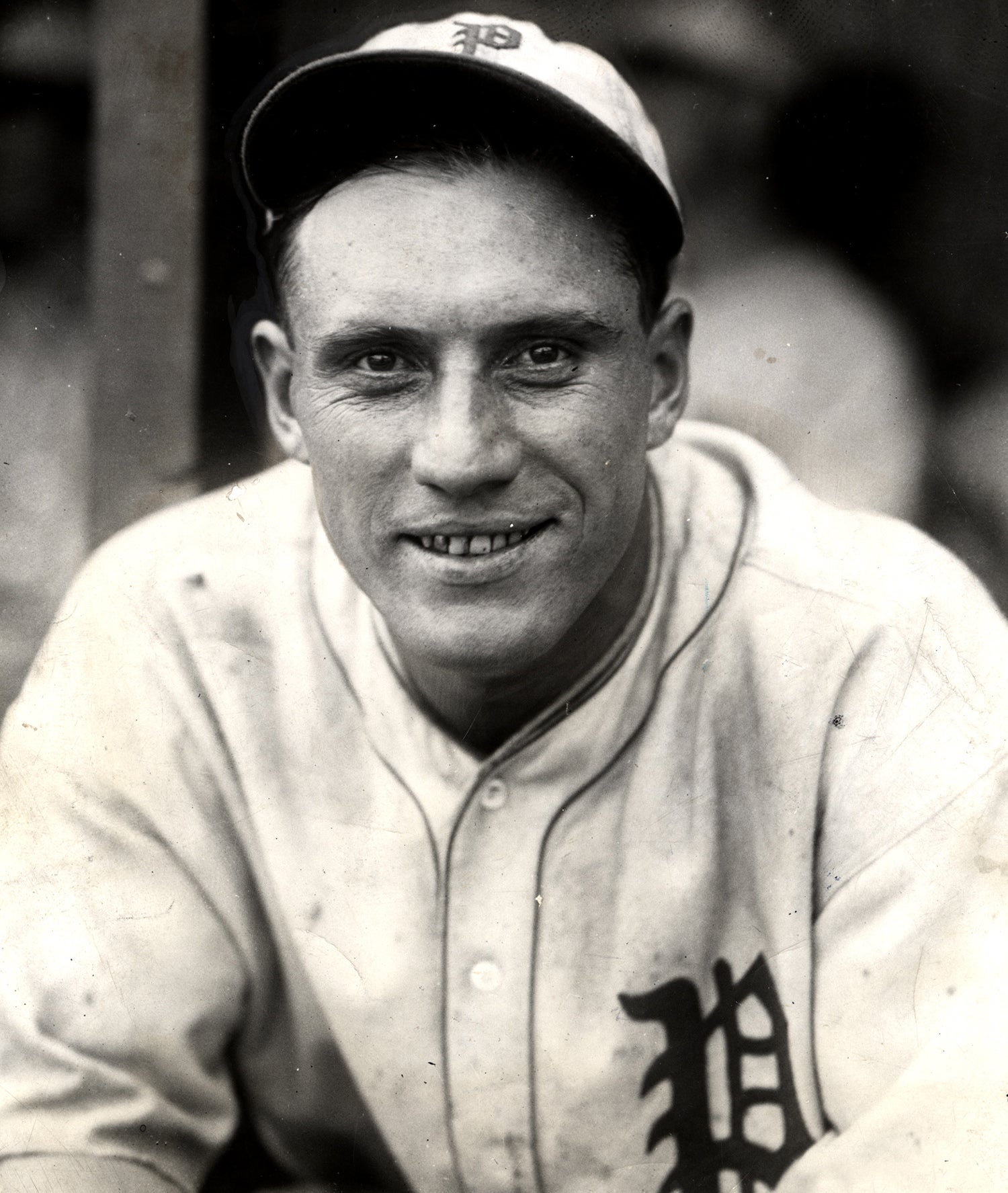

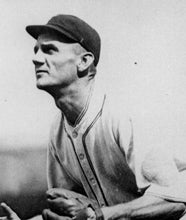

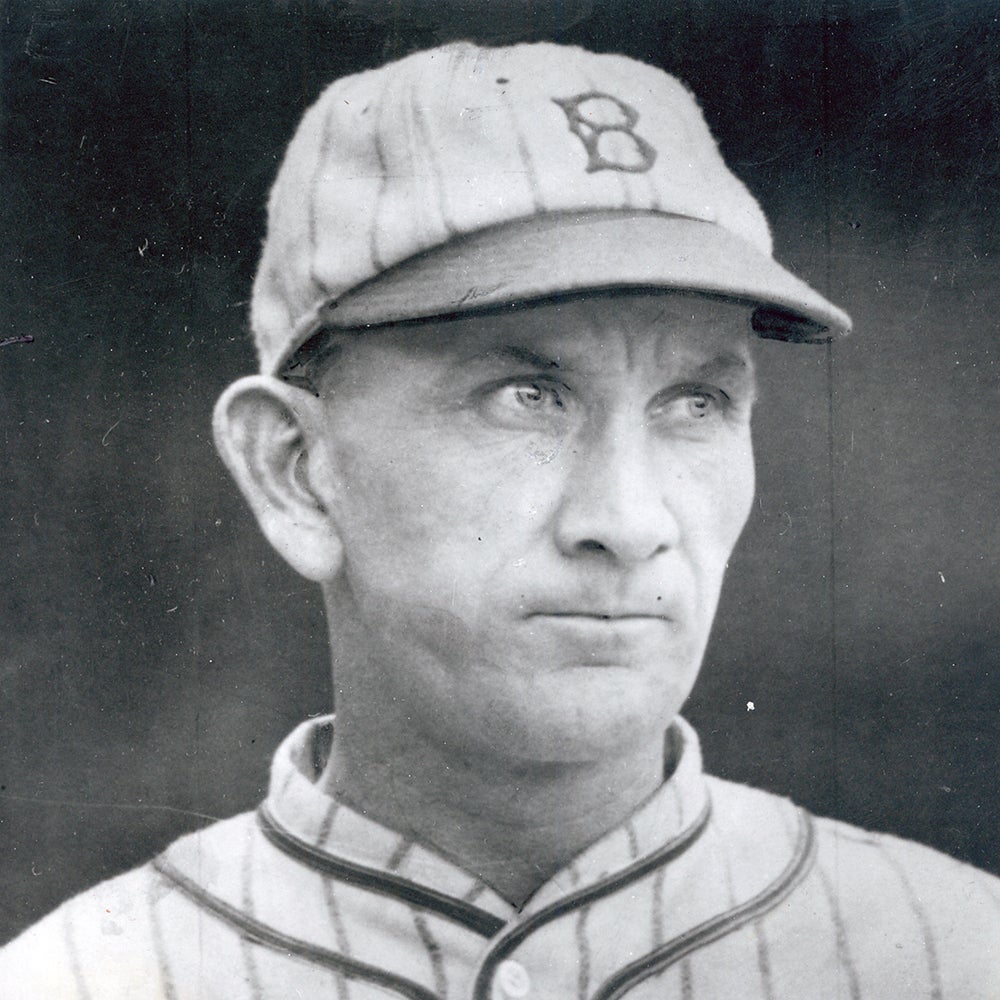

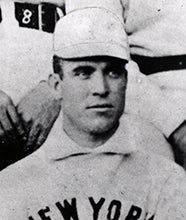

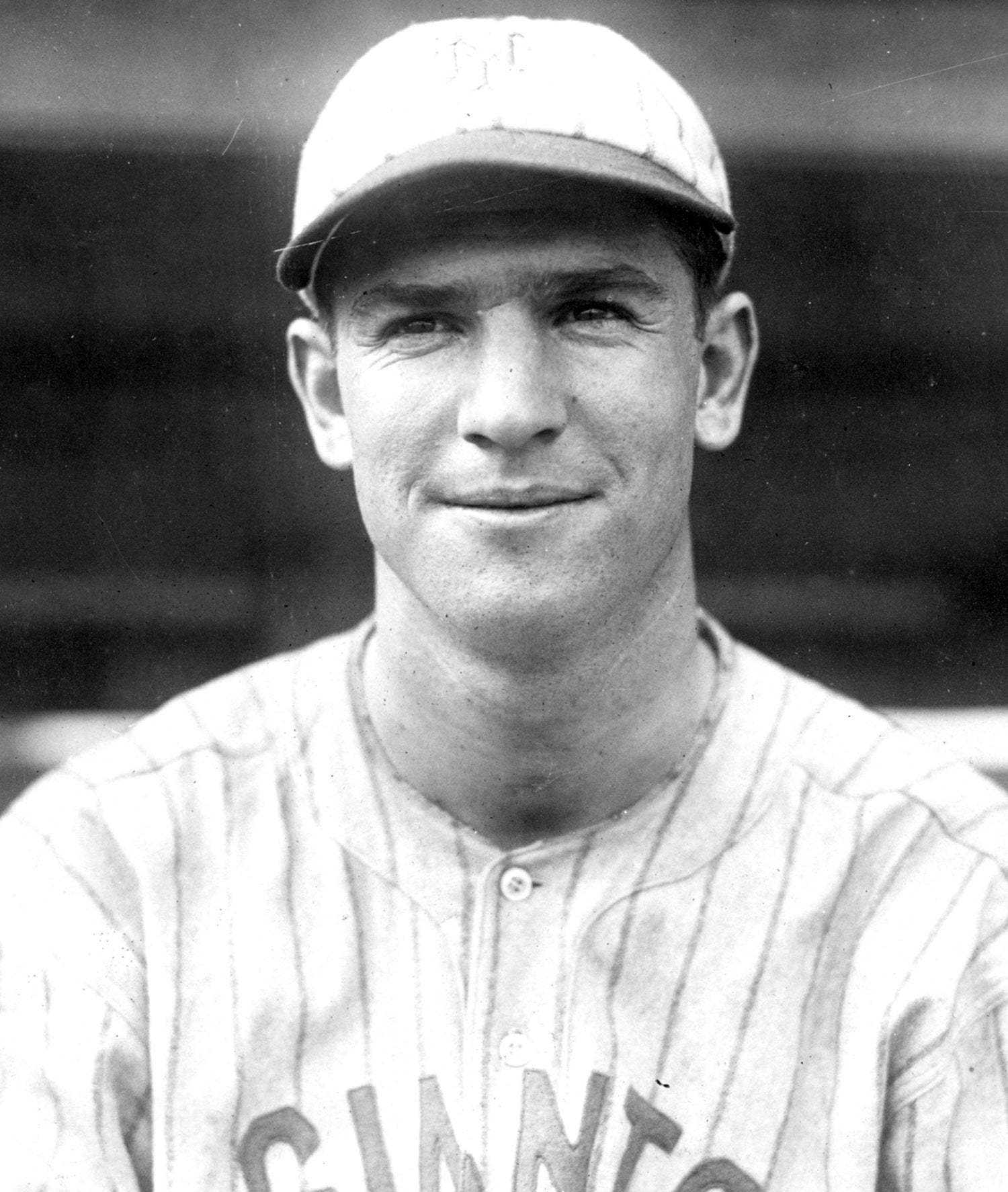

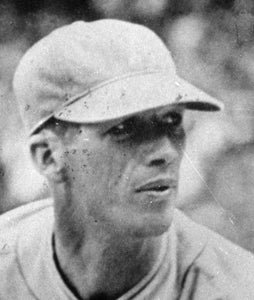

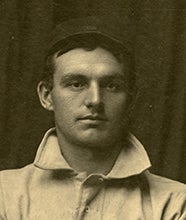

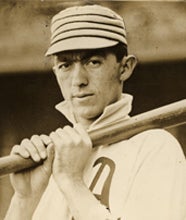

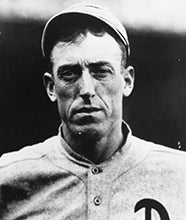

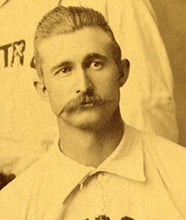

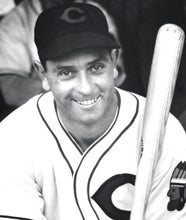

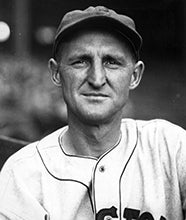

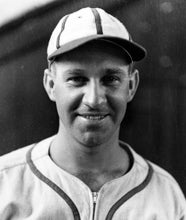

He never played a game in baseball’s “modern” era. But Adrian Constantine “Cap” Anson was one of the great modernizers of the game, bringing strategy and leadership to the National Pastime.

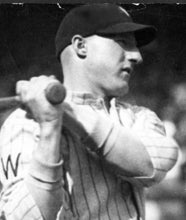

Anson, born April 17, 1852 in Marshalltown, Iowa, spent a year at the University of Notre Dame before making his big league debut in the first year of the first pro league: The National Association of 1871. Anson was a 19-year-old third baseman for the Rockford Forest Citys, and the 6-foot, 227-pound strapping right-hander hit .325 with a league-leading 11 doubles. The next season, Anson hit .415 for the Philadelphia Athletics of the NA, driving in 48 runs in just 46 games.

In 1876, Chicago White Stockings president William Hulbert – looking to add talent to his club – negotiated a deal with Anson and other stars. Hulbert then helped form the National League, and that summer Anson hit .356 to lead Chicago to a 52-14 record and the first NL title.

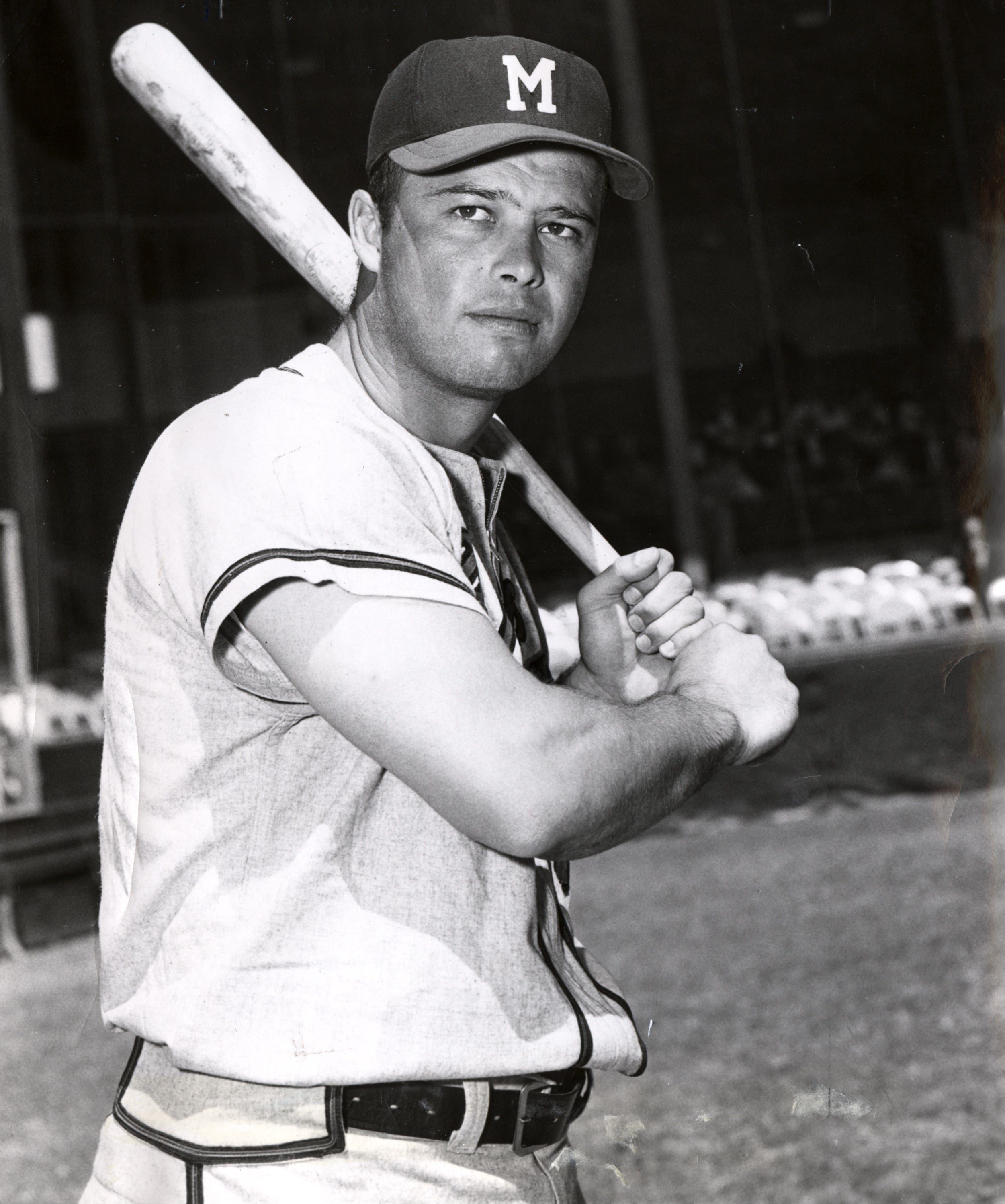

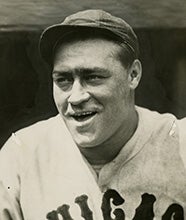

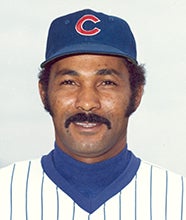

Anson would play 22 seasons for the team that became the Cubs, hitting at least .300 in 20 of those years. He moved across the diamond to first base in 1879, and led the league in RBI eight times between 1880 and 1891, winning batting titles in 1881, 1887 and 1888.

When he retired after the 1897 season at the age of 45, Anson owned big league records for games, hits, at-bats, doubles and runs. He finished with 3,435 hits, becoming the first player ever to cross the 3,000-hit line.

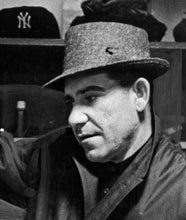

Anson also managed Chicago for 19 seasons, winning five National League pennants as a player/manager while accumulating almost 1,300 career victories. He helped usher in popular strategies such as the hit-and-run and the pitching rotation.

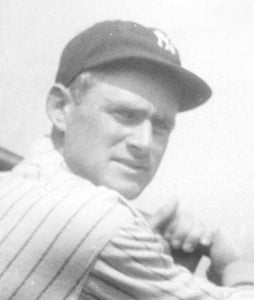

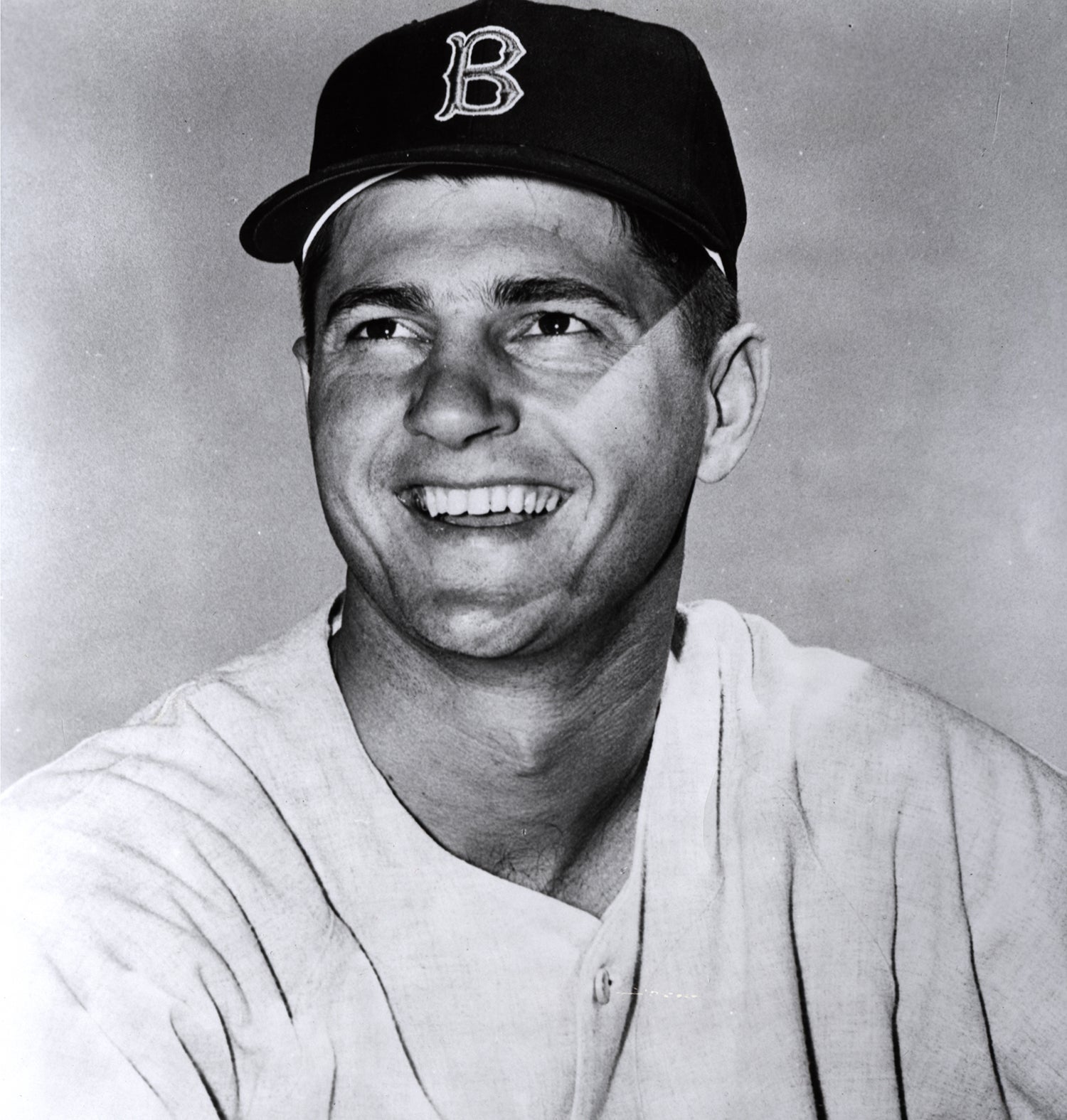

After leaving Chicago following the 1897 season, Anson managed the New York Giants for 22 games in 1898 before ending his big league career. In his later years, he ran several semi-pro teams and ventured into the vaudeville circuit.

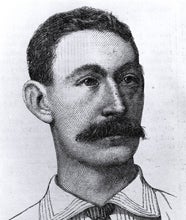

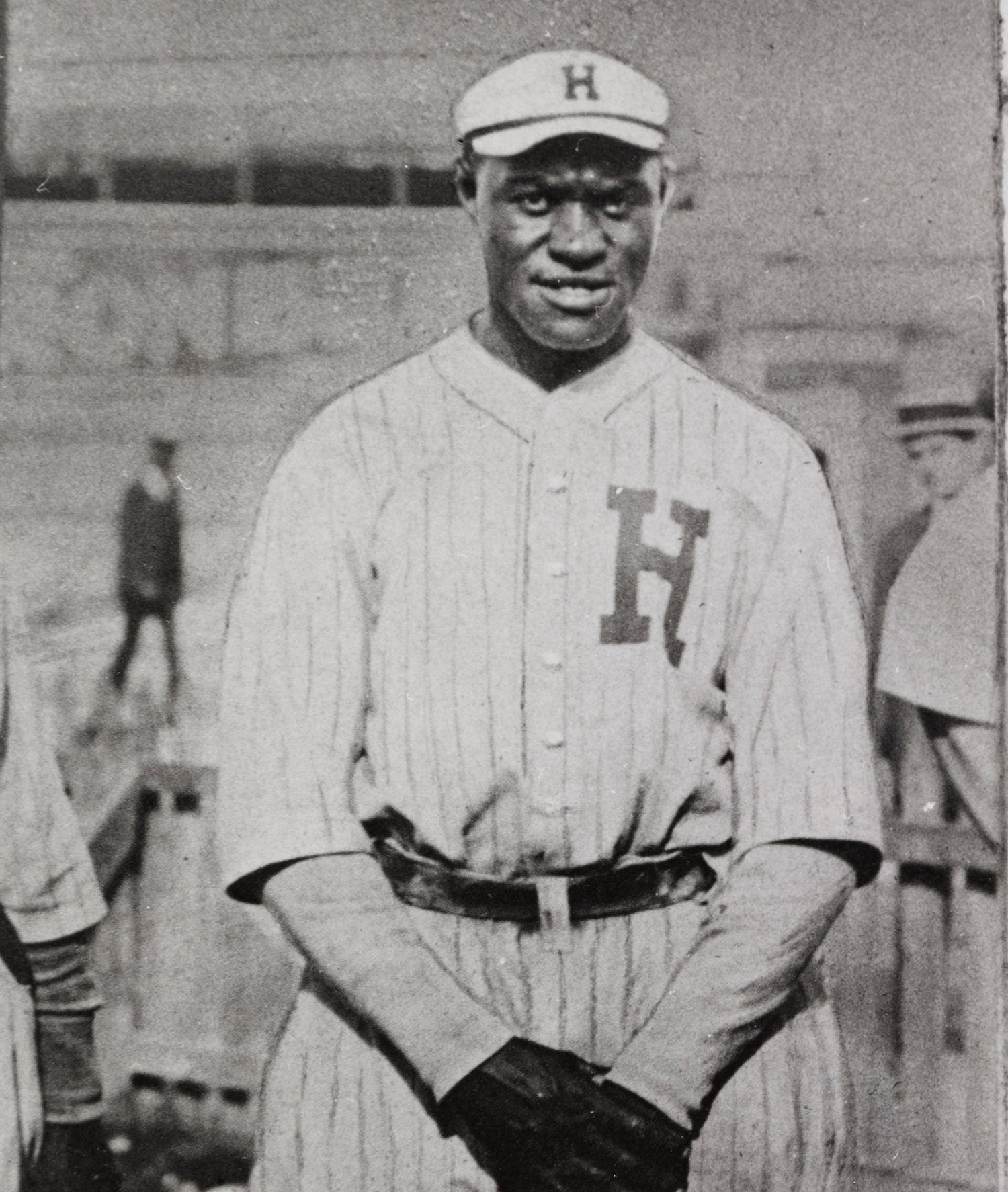

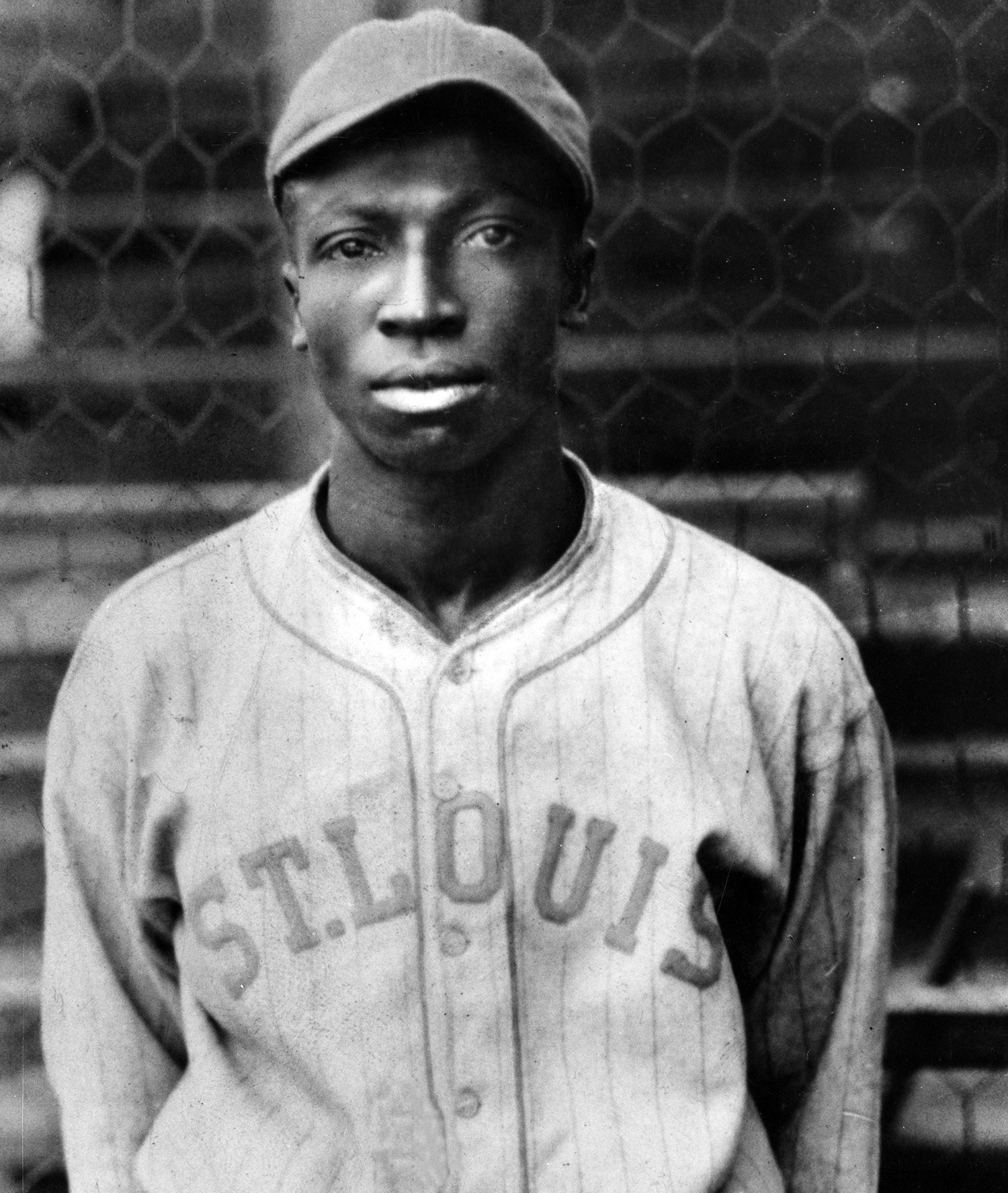

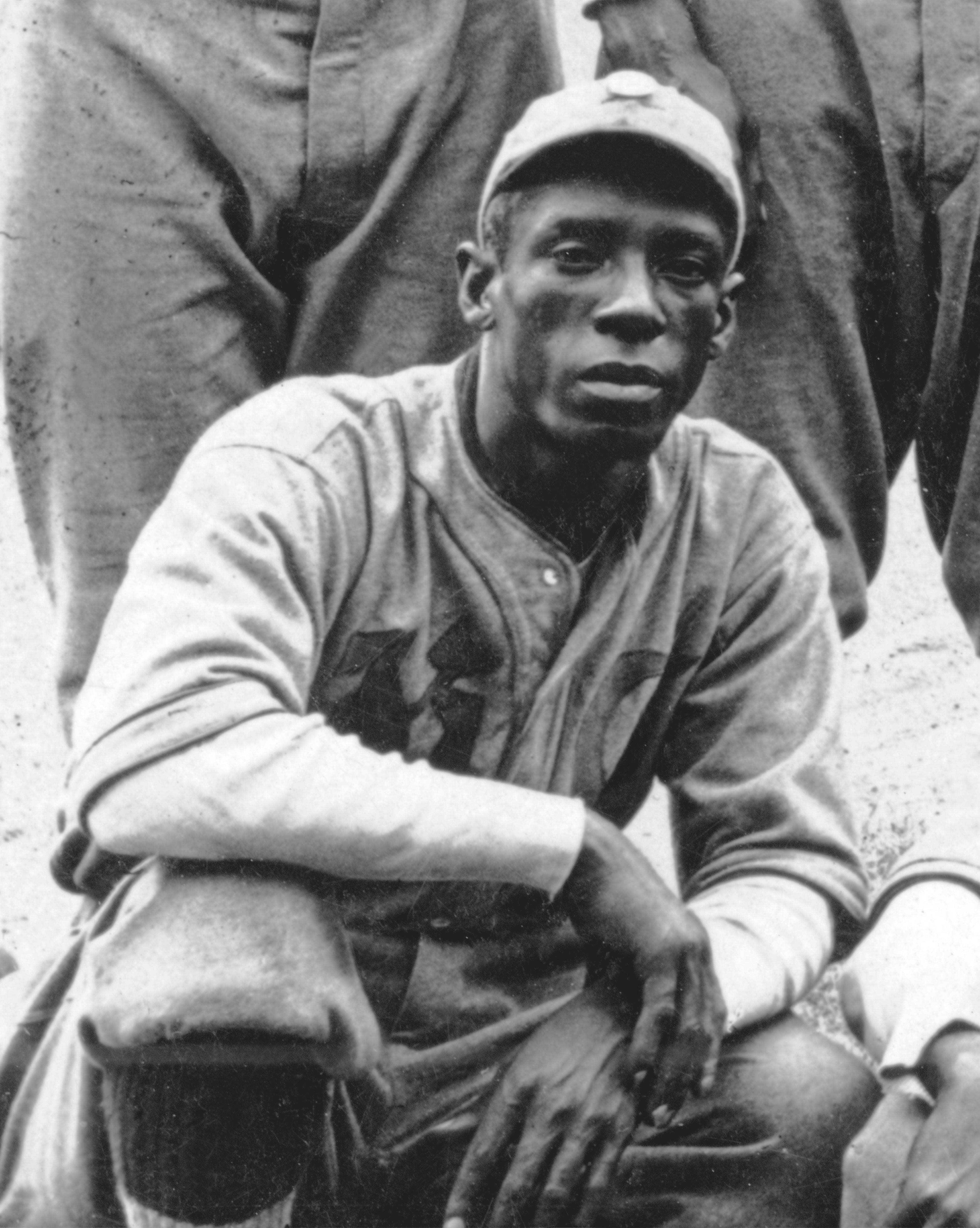

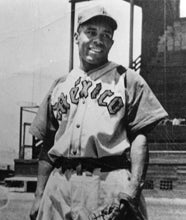

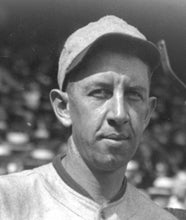

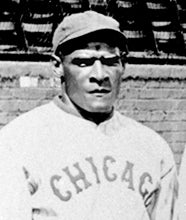

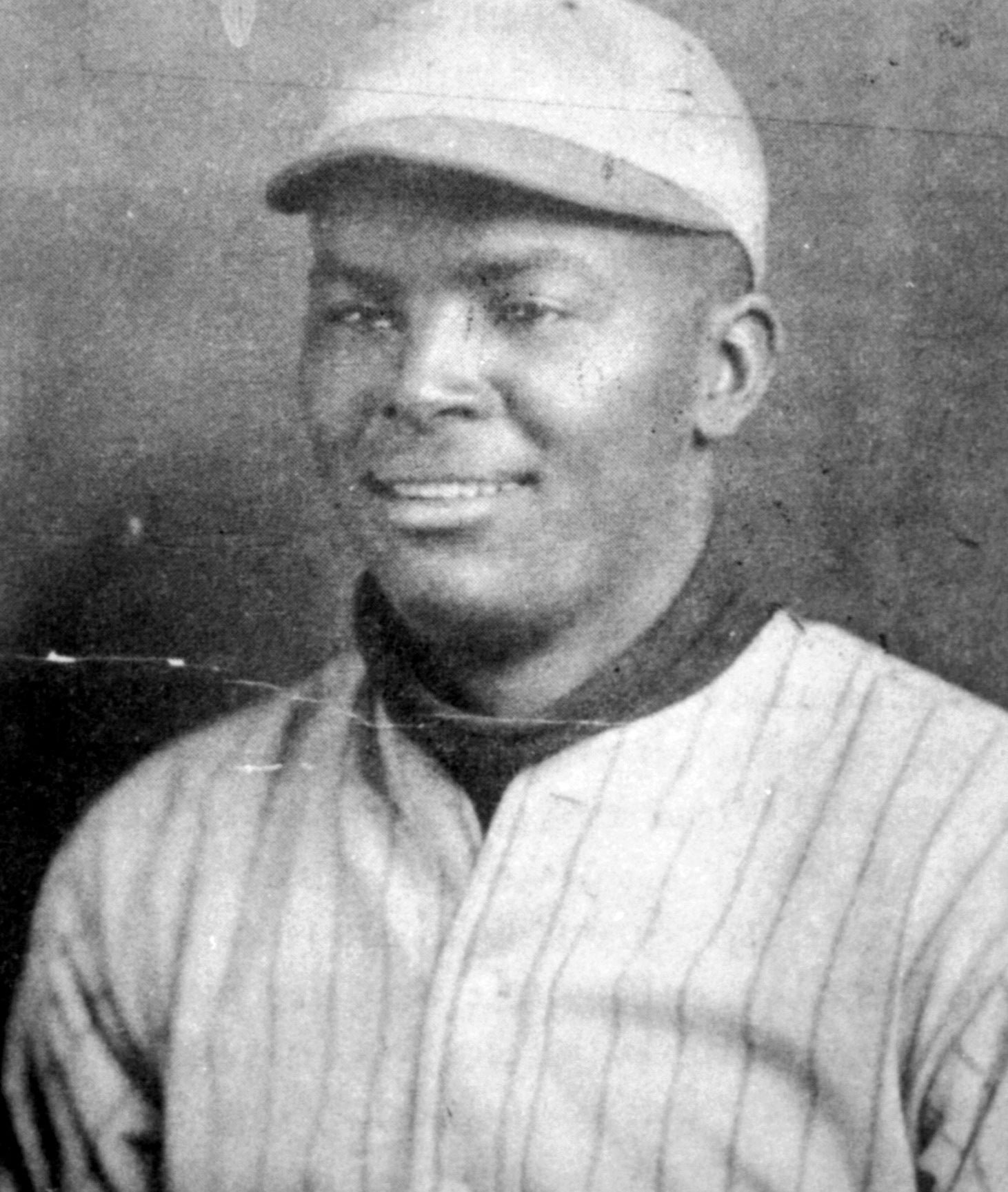

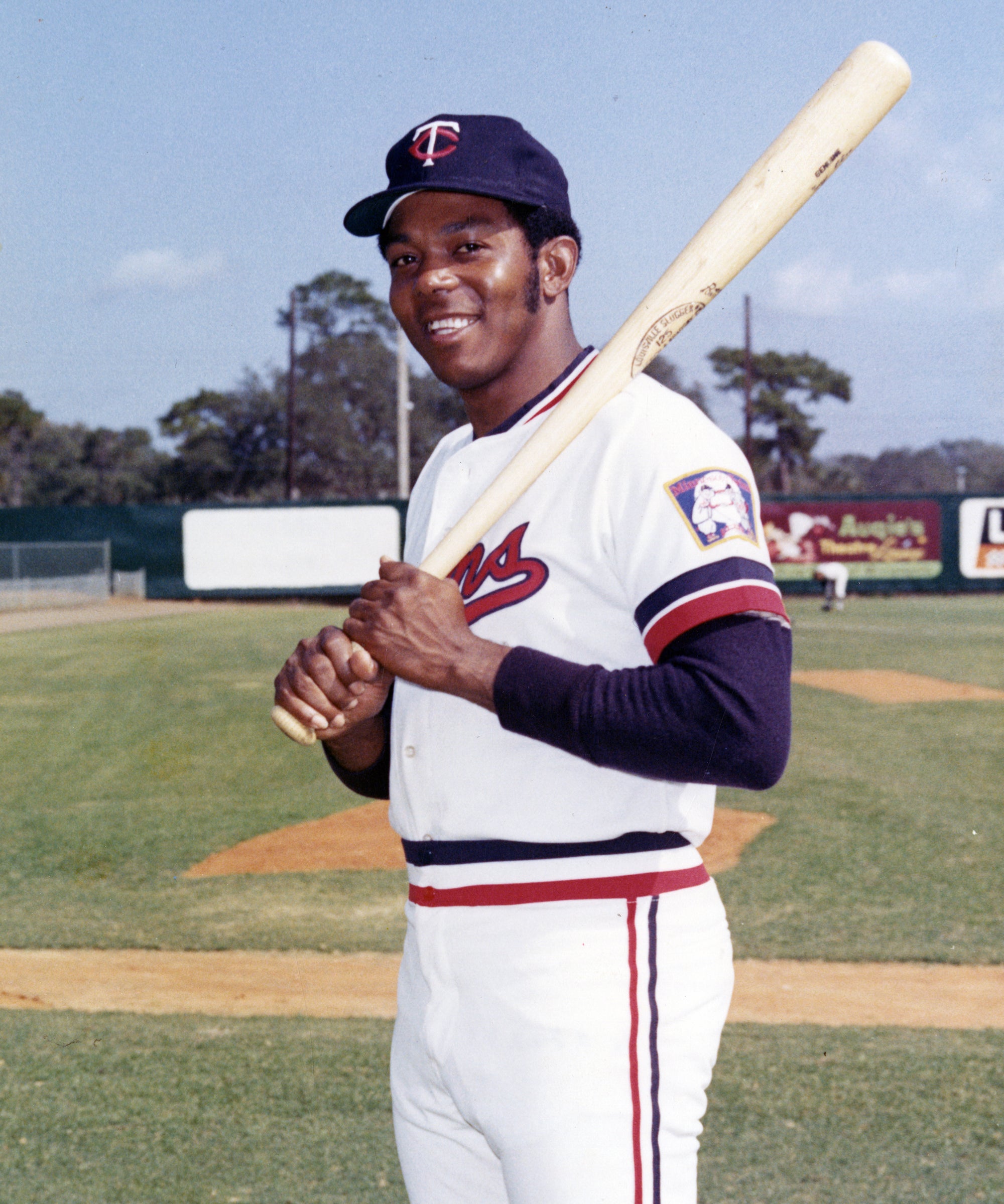

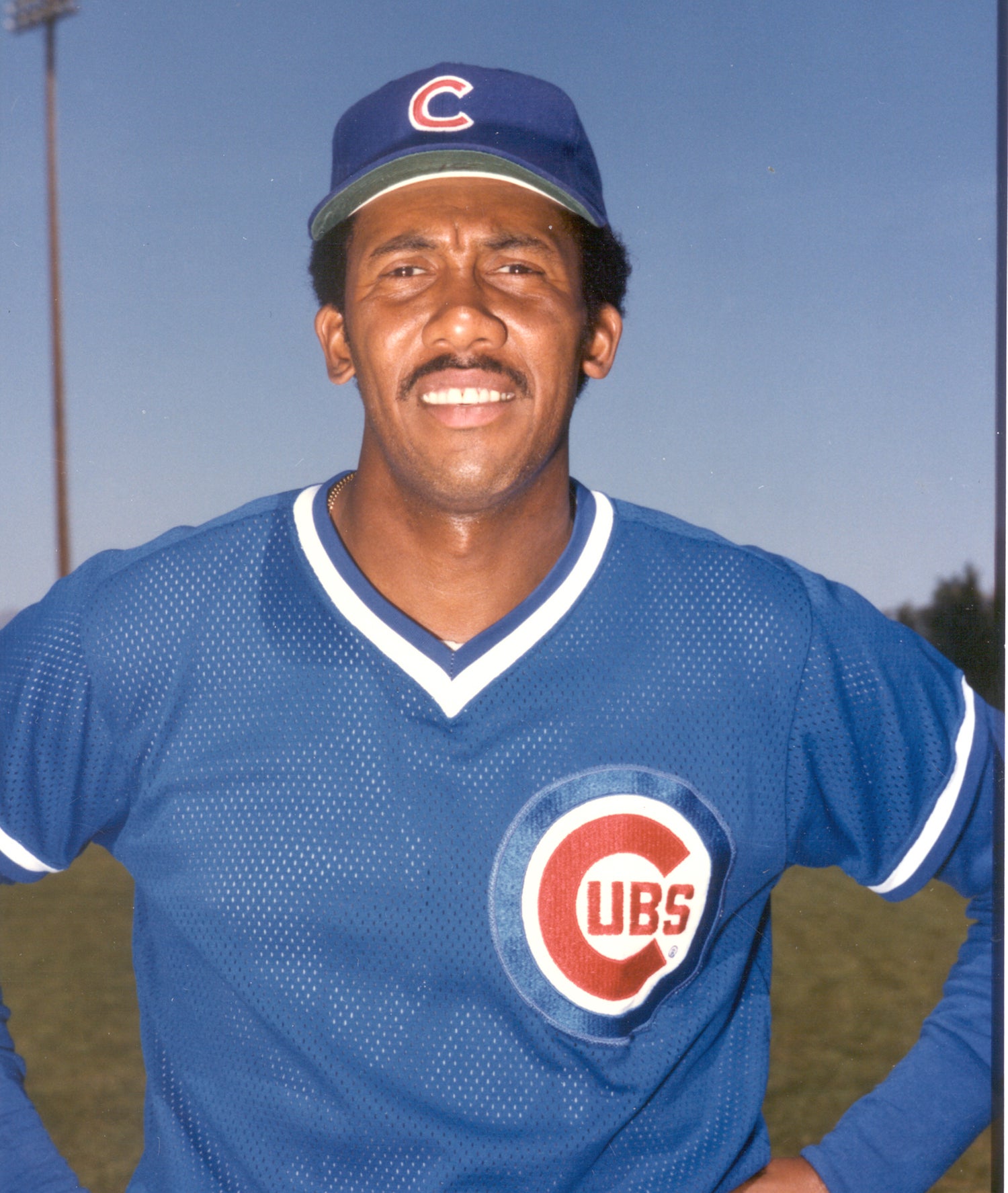

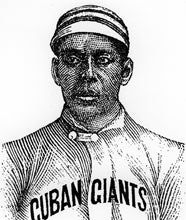

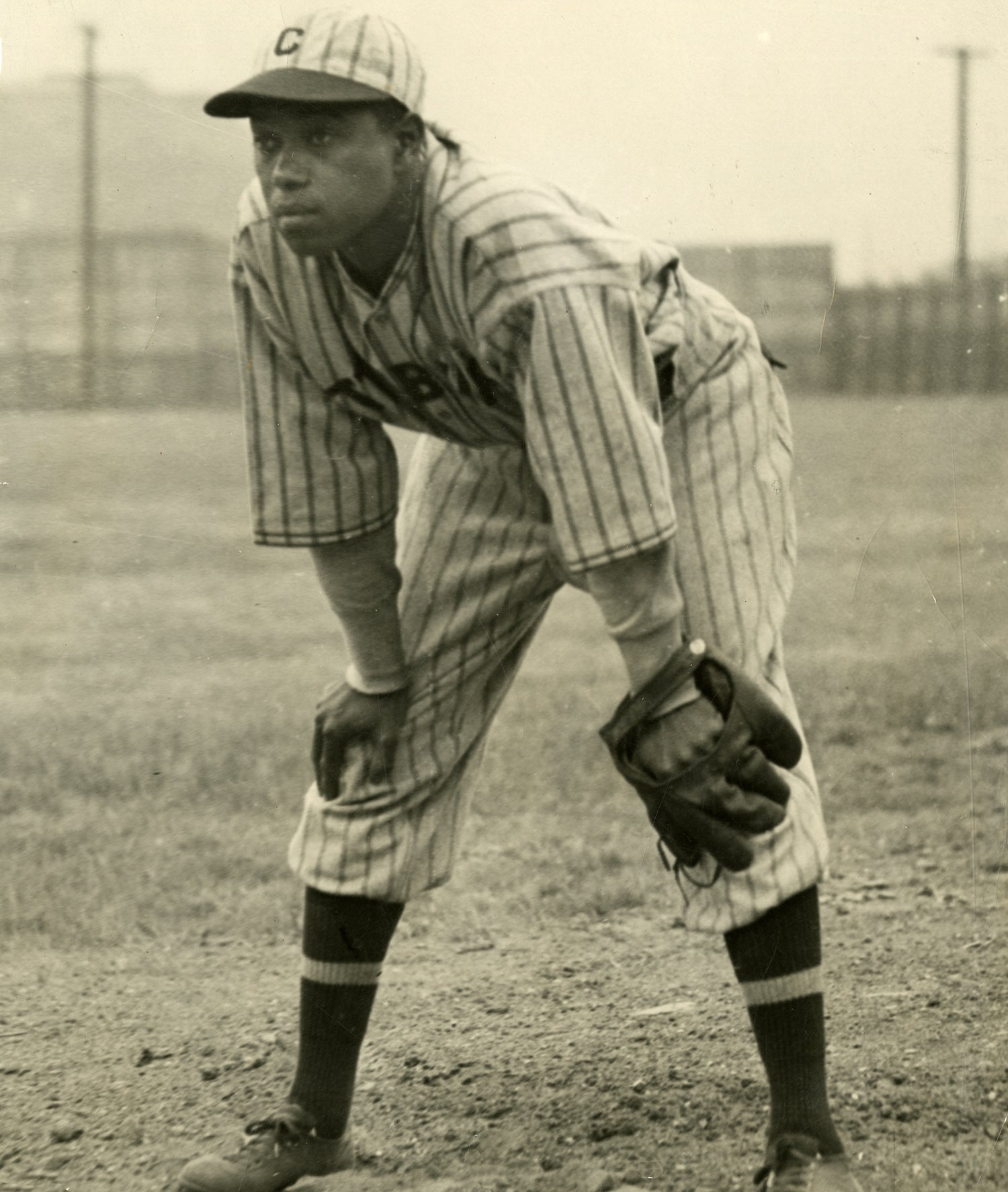

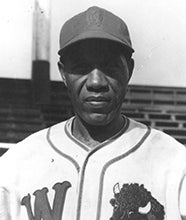

An objective study of Anson’s career must also include his role in the game’s segregation. Hall of Famer Sol White, historian of early Black baseball and player-manager for the all-Black Philadelphia Giants, emphasized Cap Anson’s part in keeping big league baseball segregated, recalling that the white manager claimed he would never step on a field that also had a Black man on it.

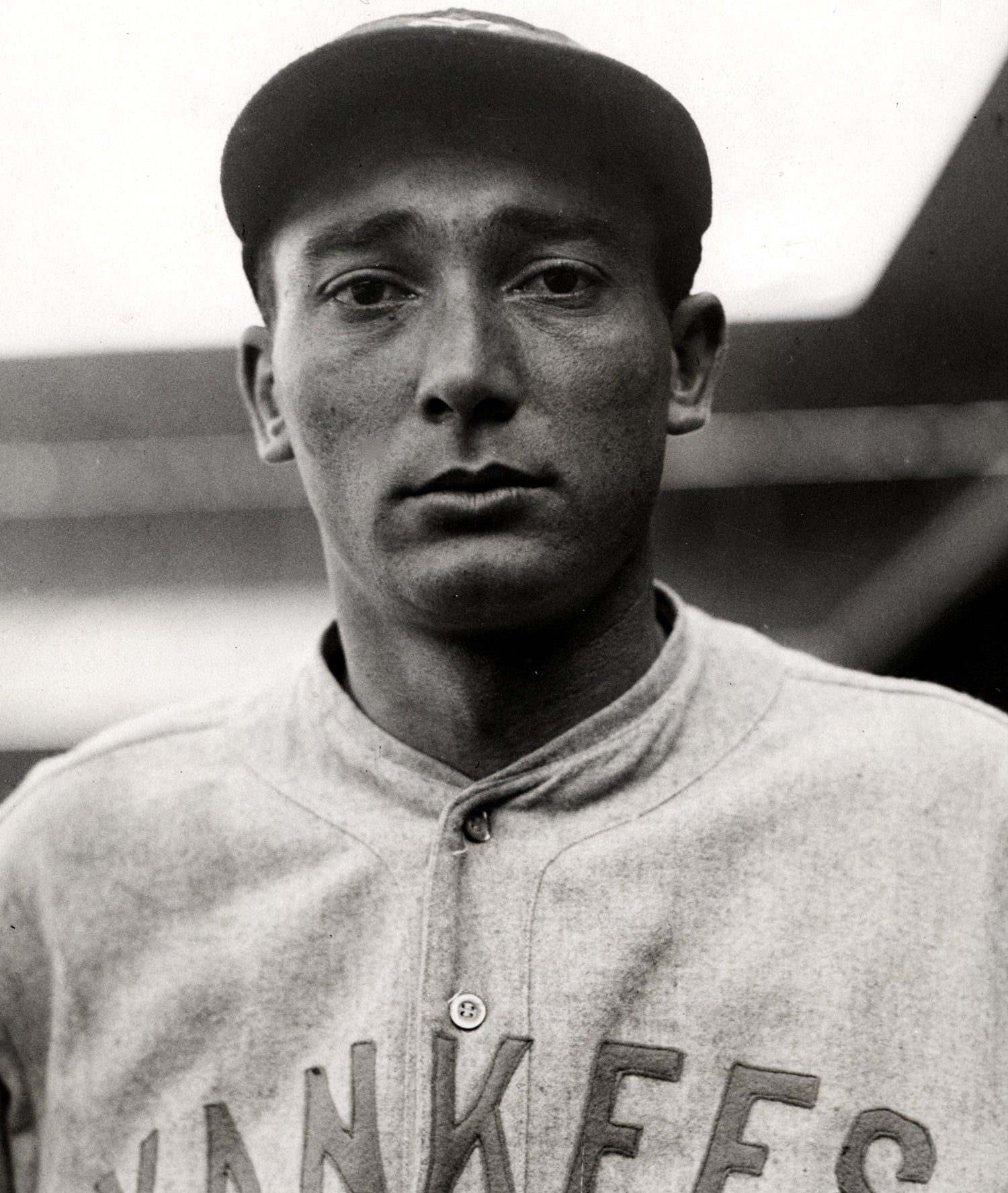

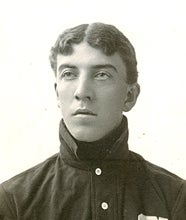

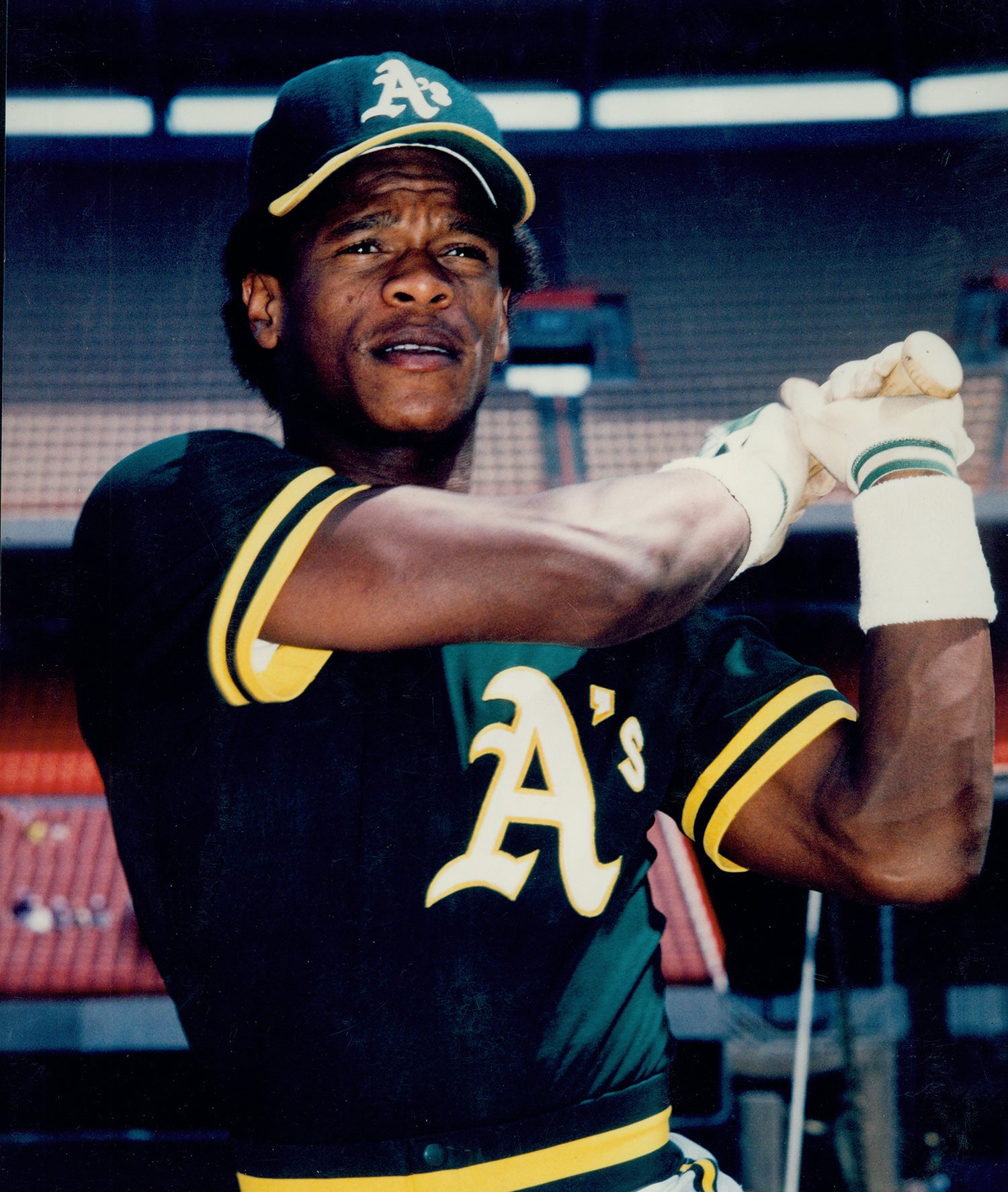

During Anson’s tenure as Chicago’s manager, he refused to play against teams with Black players, including an exhibition game in 1887 versus a Newark team featuring an all-Black battery of Moses Fleetwood Walker and George Stovey. Anson’s racism may have been common by the day’s standards, but his influence and stature gave his actions additional impact and supported the segregationist attitudes that impeded the game for another six decades.

Anson passed away on April 14, 1922. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1939.