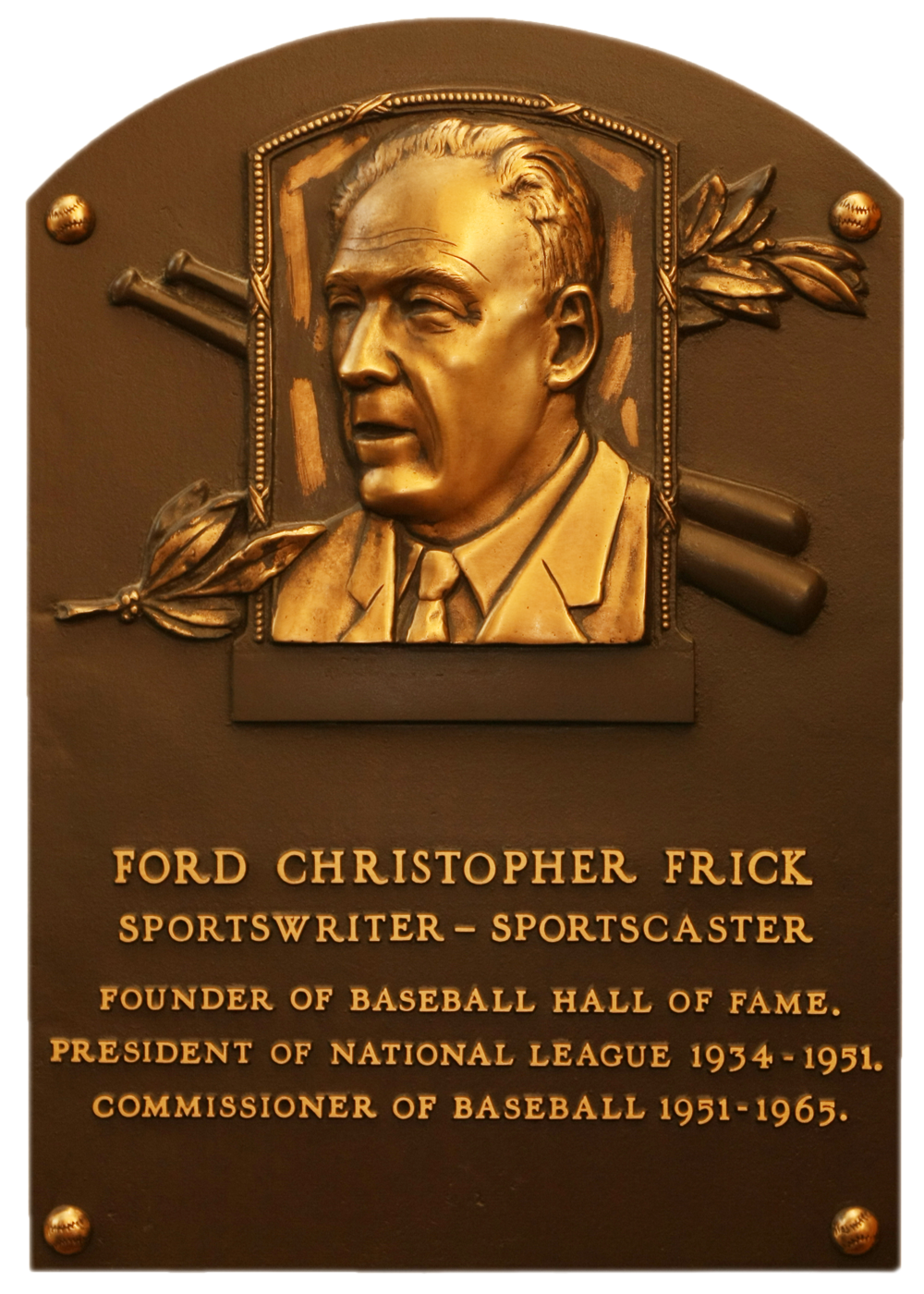

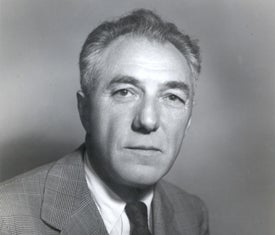

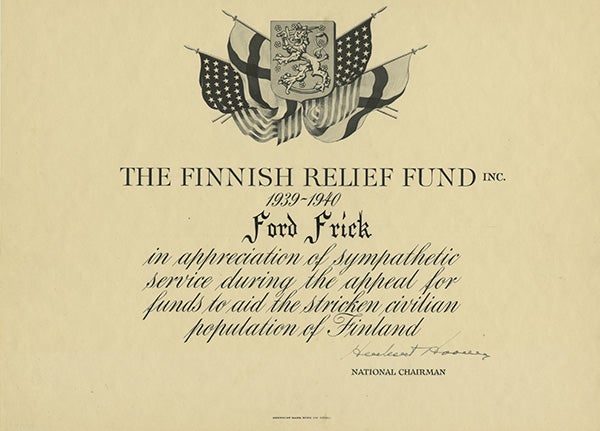

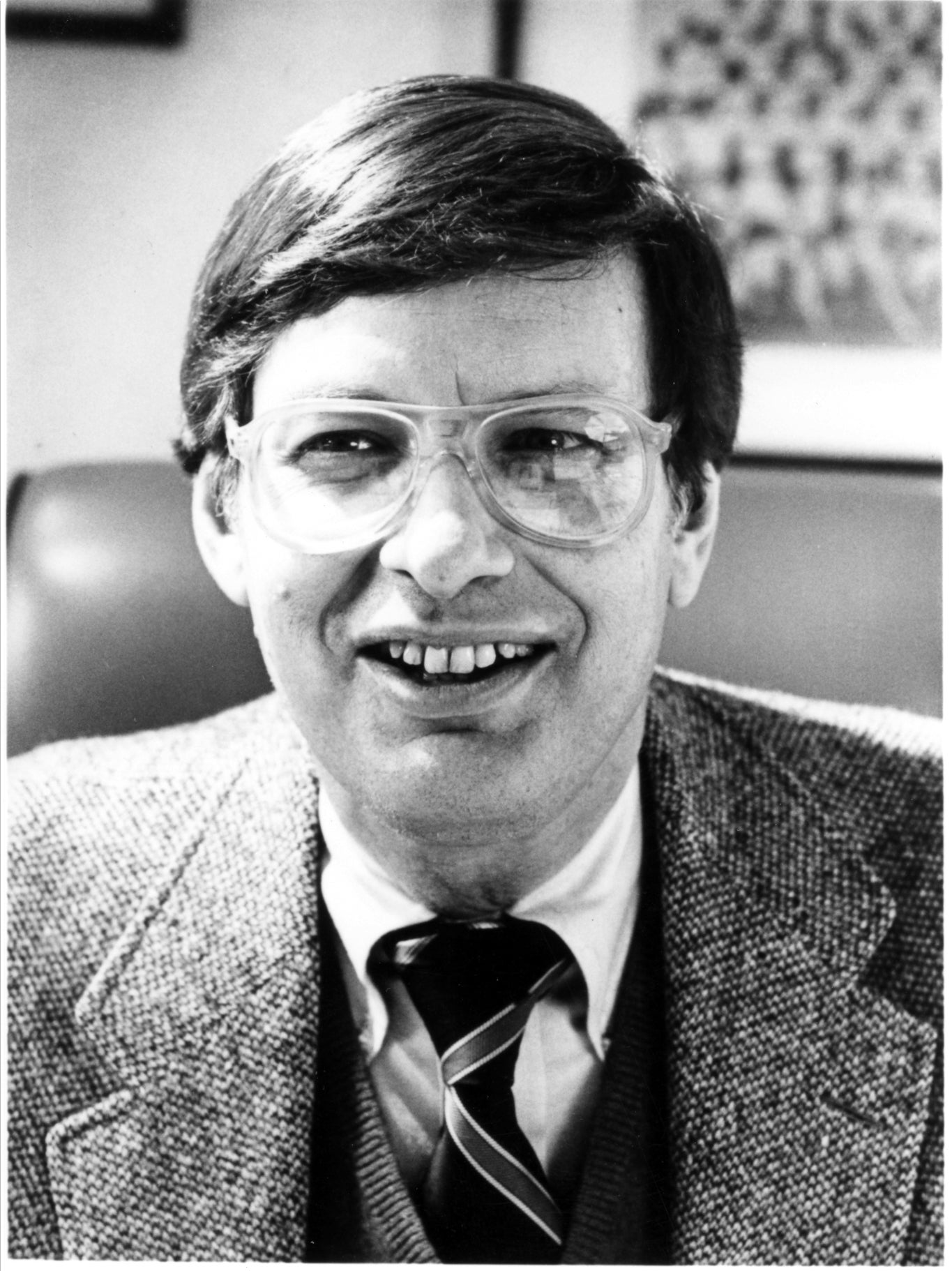

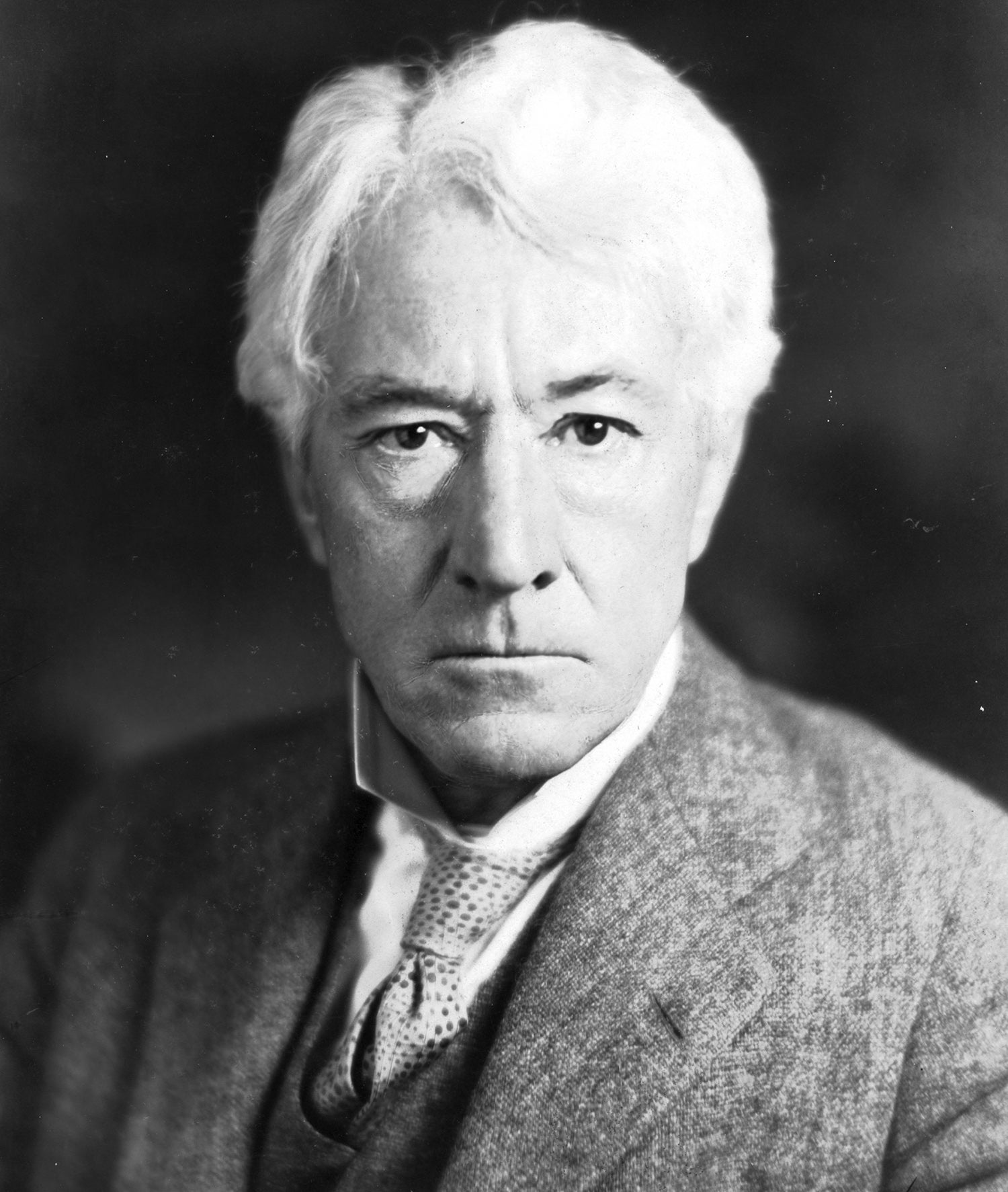

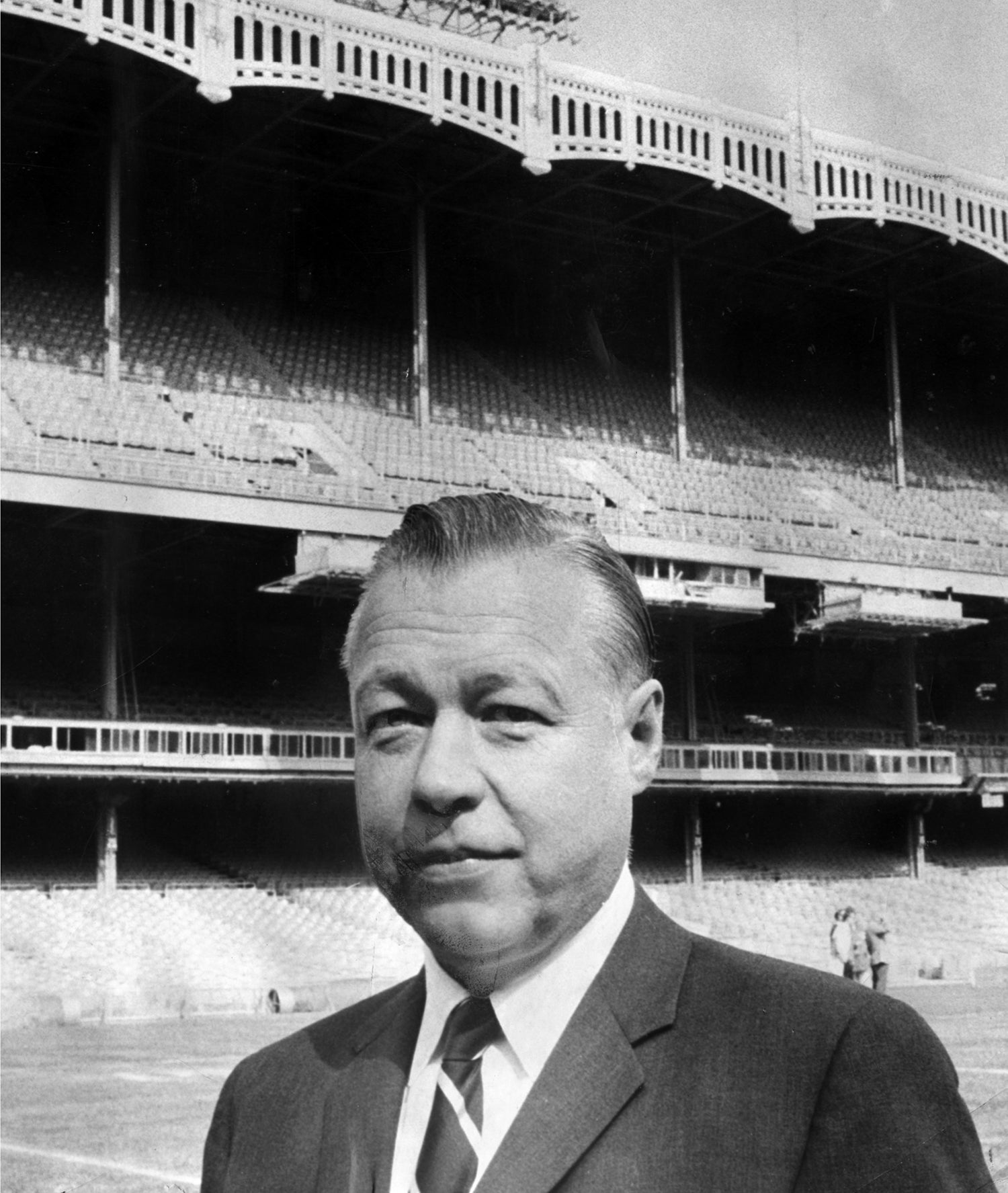

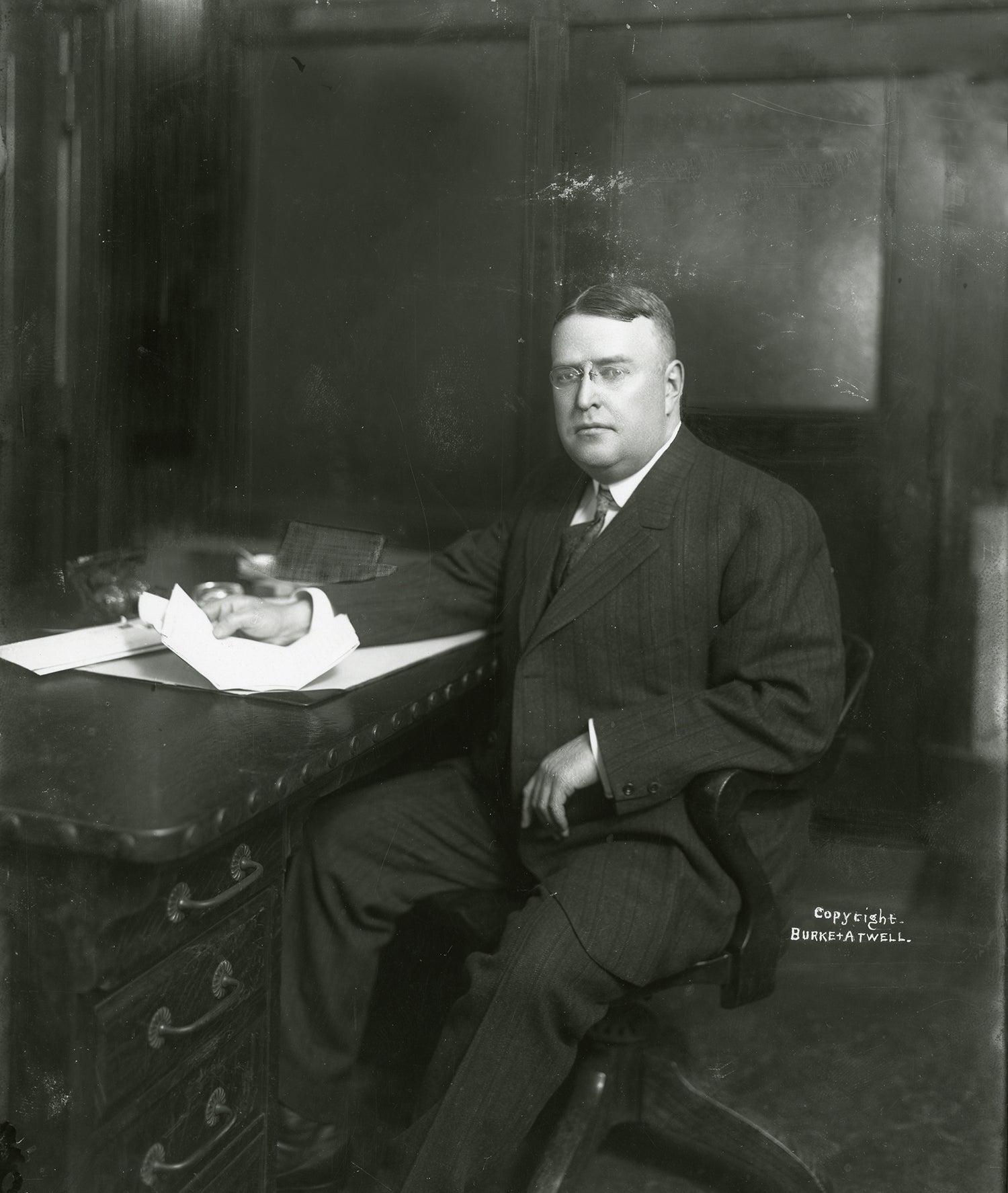

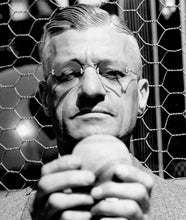

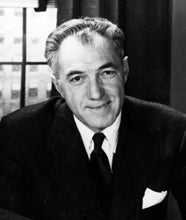

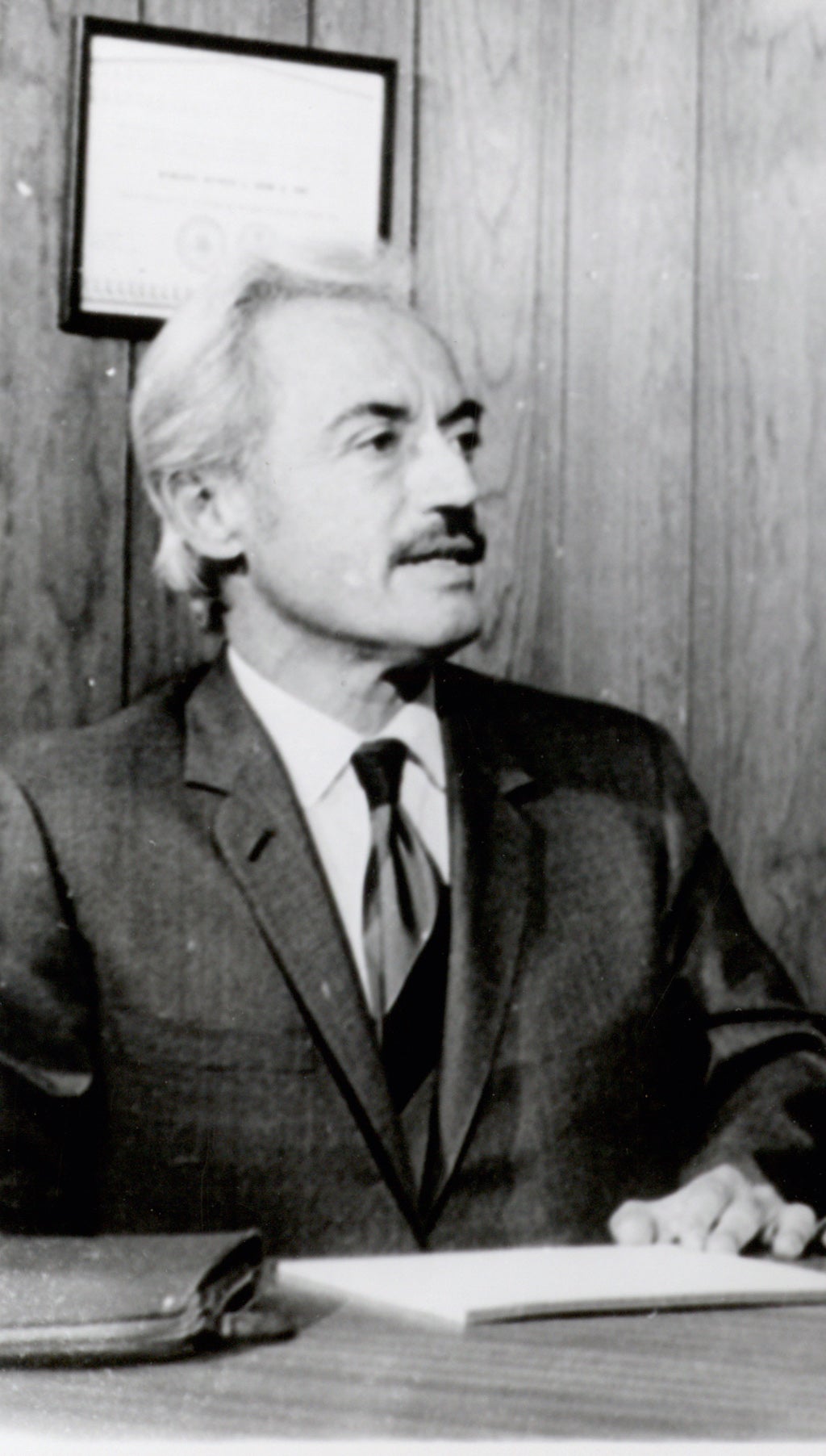

Through an unlikely path from Colorado sportswriter to commissioner of baseball, Ford C. Frick oversaw monumental changes and achievements during his 31 years of leadership in the game.

He also helped ensure those achievements would be preserved forever in Cooperstown, N.Y.

Frick was a sportswriter and high school English teacher in Colorado Springs when he was invited to join the staff of the New York American in 1922. It was the first of a series of historic events in Frick’s life when he was, as he put it, in “the right place at the right time.”

Frick covered the New York Yankees for the American and later the New York Evening Journal from 1923-34, and was the ghostwriter for "Babe Ruth’s Own Book of Baseball" in 1928. In 1930, Frick began broadcasting games over the radio and pioneered the daily sports report. Four years later, he was hired to be the National League’s public relations director.

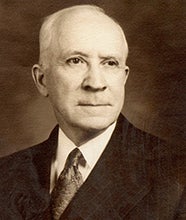

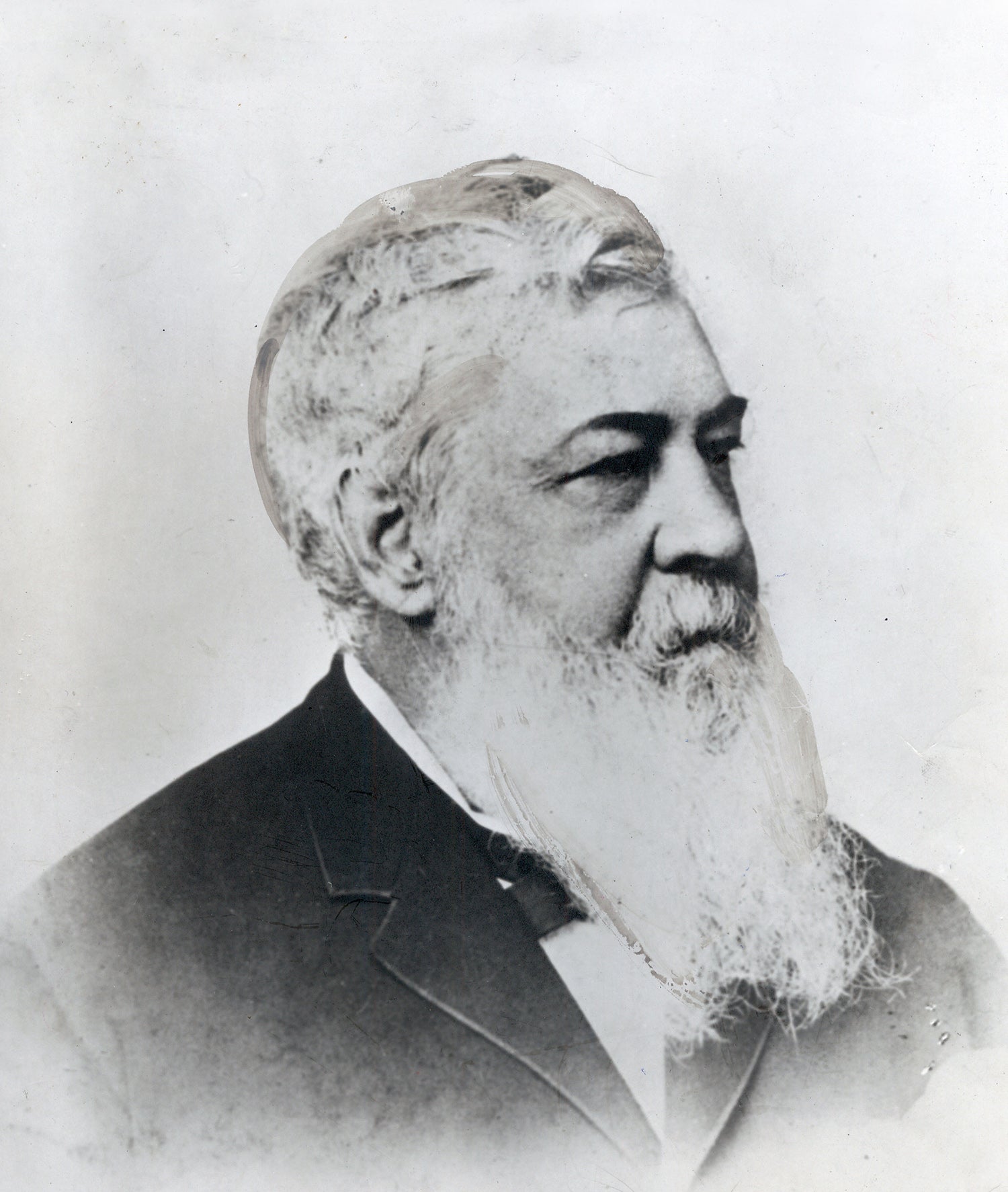

Frick held his new position for only nine months before he was elected as president of the National League after outgoing president John A. Heydler resigned because of poor health. Soon after assuming his new role, Frick campaigned for a Hall of Fame that would honor baseball’s greatest baseball players.

“Why not start a baseball museum, and a Hall of Fame, and have something that will last?” Frick asked his fellow executives. His vision and that of Museum founder Stephen C. Clark was quickly realized when the National Baseball Museum, as it was then called, opened its doors on June 12, 1939.

When Frick was elected National League president, a handful of teams including the Boston Braves, Brooklyn Dodgers, Cincinnati Reds and Philadelphia Phillies were in financial peril due to the Great Depression.

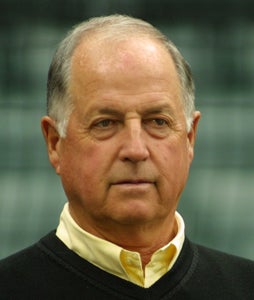

“There were several franchises that might have gone by the boards,” said Red Patterson, a longtime executive with the Dodgers and Angels. “(Frick) did a great job of bringing in money and leadership. The man played a major part in the development of the National League, in making it the great league it is today.”

In 1947, Frick threatened to ban players on the St. Louis Cardinals who had proposed to sit out in response to Jackie Robinson’s debut in the National League.

“If you do this you are through, and I don’t care if it wrecks the league for 10 years,” Frick told the strikers. “You cannot do this, because this is America.”

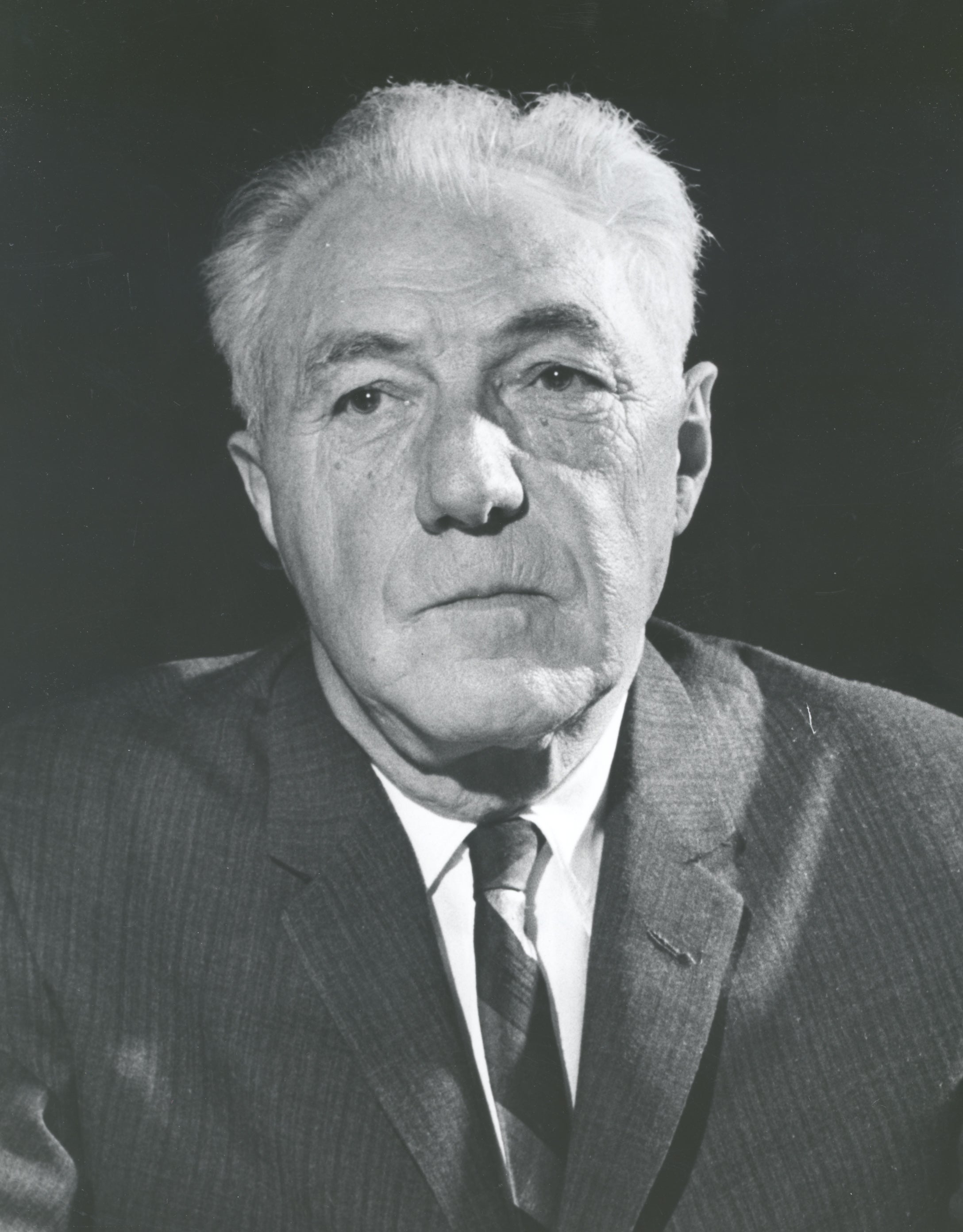

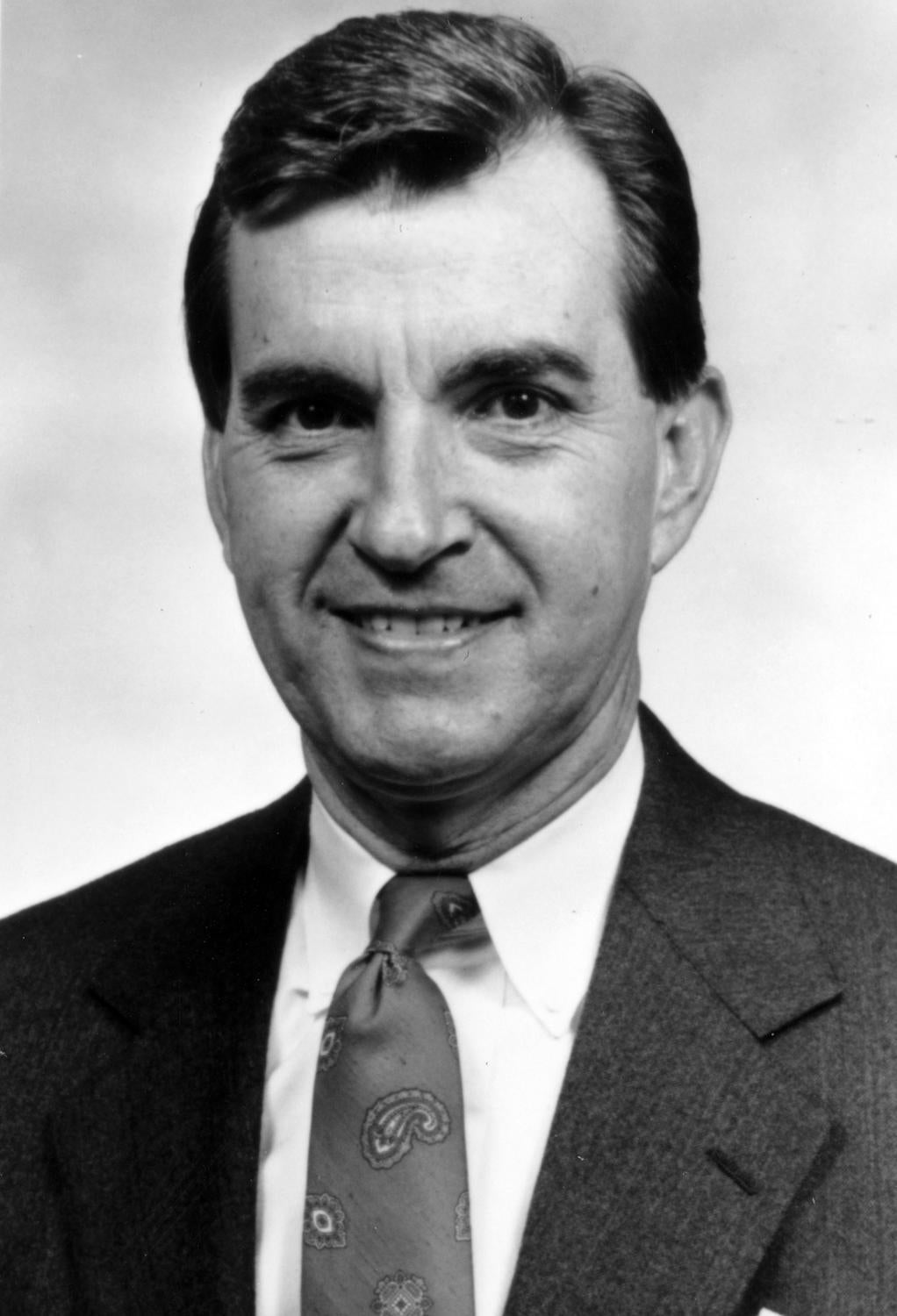

When commissioner Happy Chandler was dismissed by the owners in 1951, Frick was elected to take his place. Though he was known for his restraint and commitment to stability, Frick oversaw a period of huge growth in baseball. Both leagues expanded from eight to 10 teams, with new ball clubs established in New York, Los Angeles, Houston and Washington, D.C. (which replaced the previous Senators franchise after it moved to the new territory of Minneapolis-St. Paul). Frick also negotiated television contracts that brought unprecedented revenue and visibility to the game.

“Through 30 years as a baseball leader, he brought the game integrity, dedication and a happy tranquility,” said Commissioner Bowie Kuhn.

Frick retired after two seven-year terms in the commissioner’s office in 1965. In 1970, he was elected as a member of the Hall of Fame, a museum he helped to create 31 years before. The Museum presented its first annual Ford C. Frick Award, given to broadcasters for major contributions to baseball, in 1978.

“The most gratifying achievement for me is right here in Cooperstown,” Frick said upon his induction. “Without the memories of the past, there could be no dreams of greatness in the future; without those passing yesterdays, there could possibly be no bright tomorrow.”

Frick passed away on April 8, 1978.