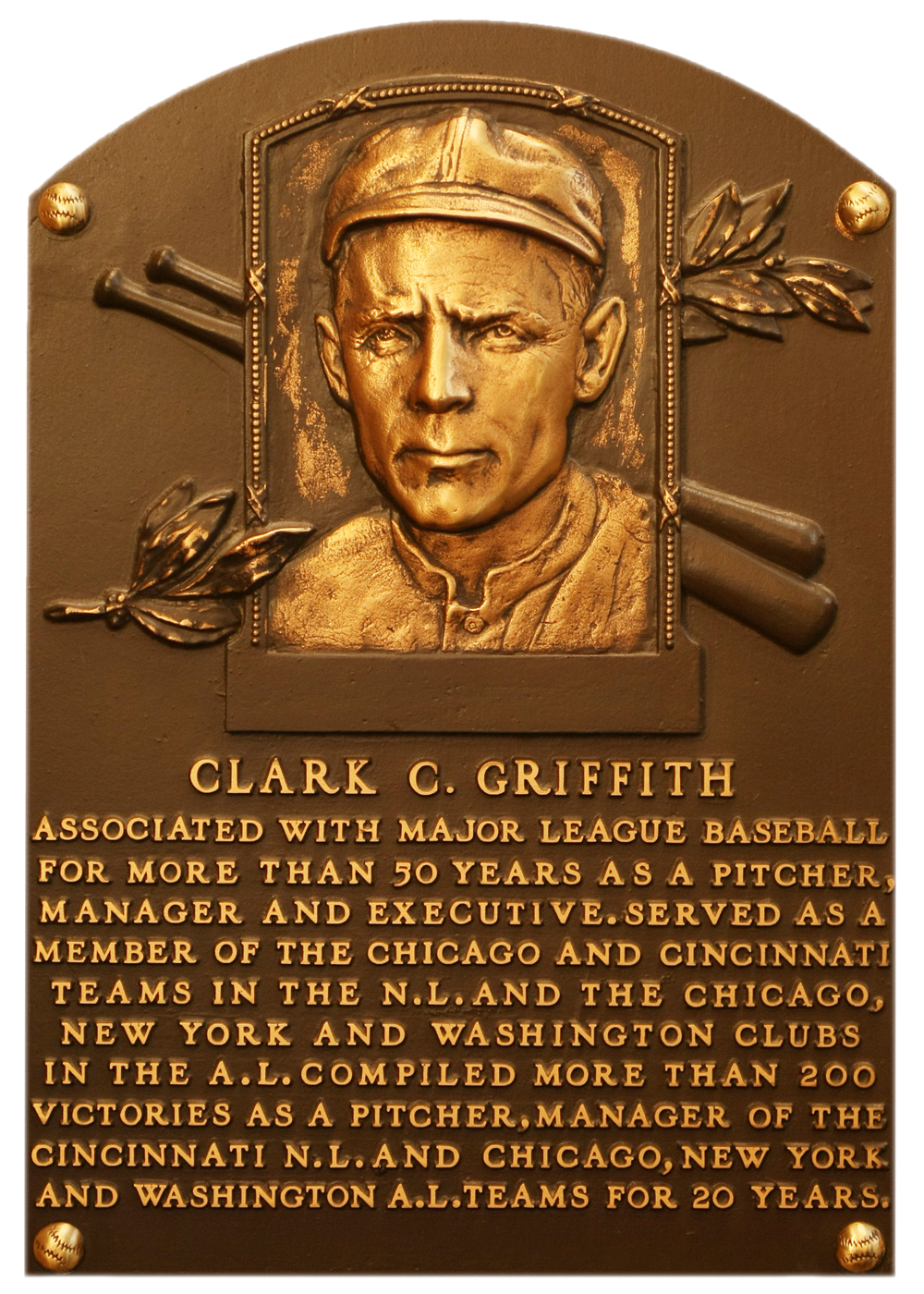

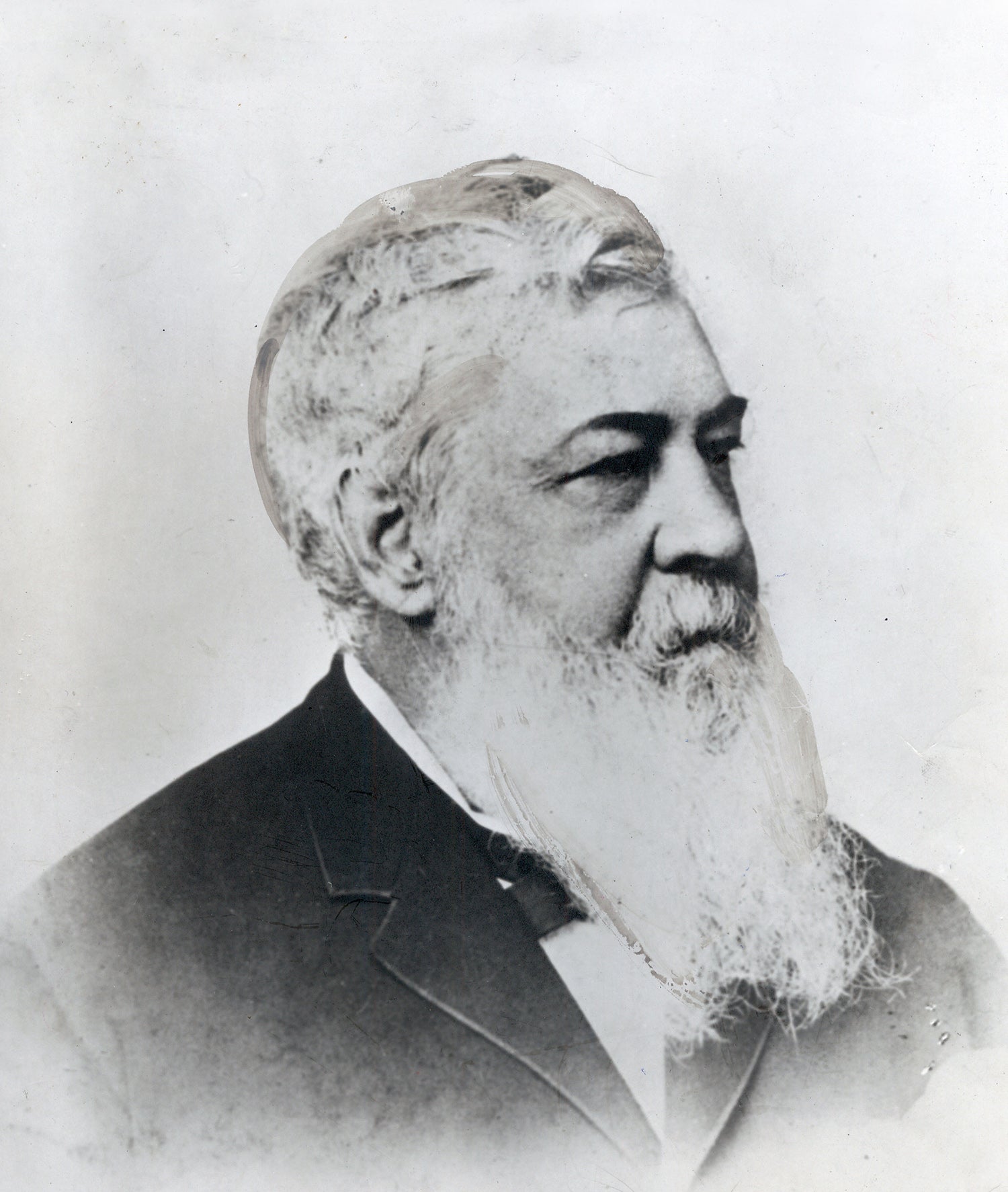

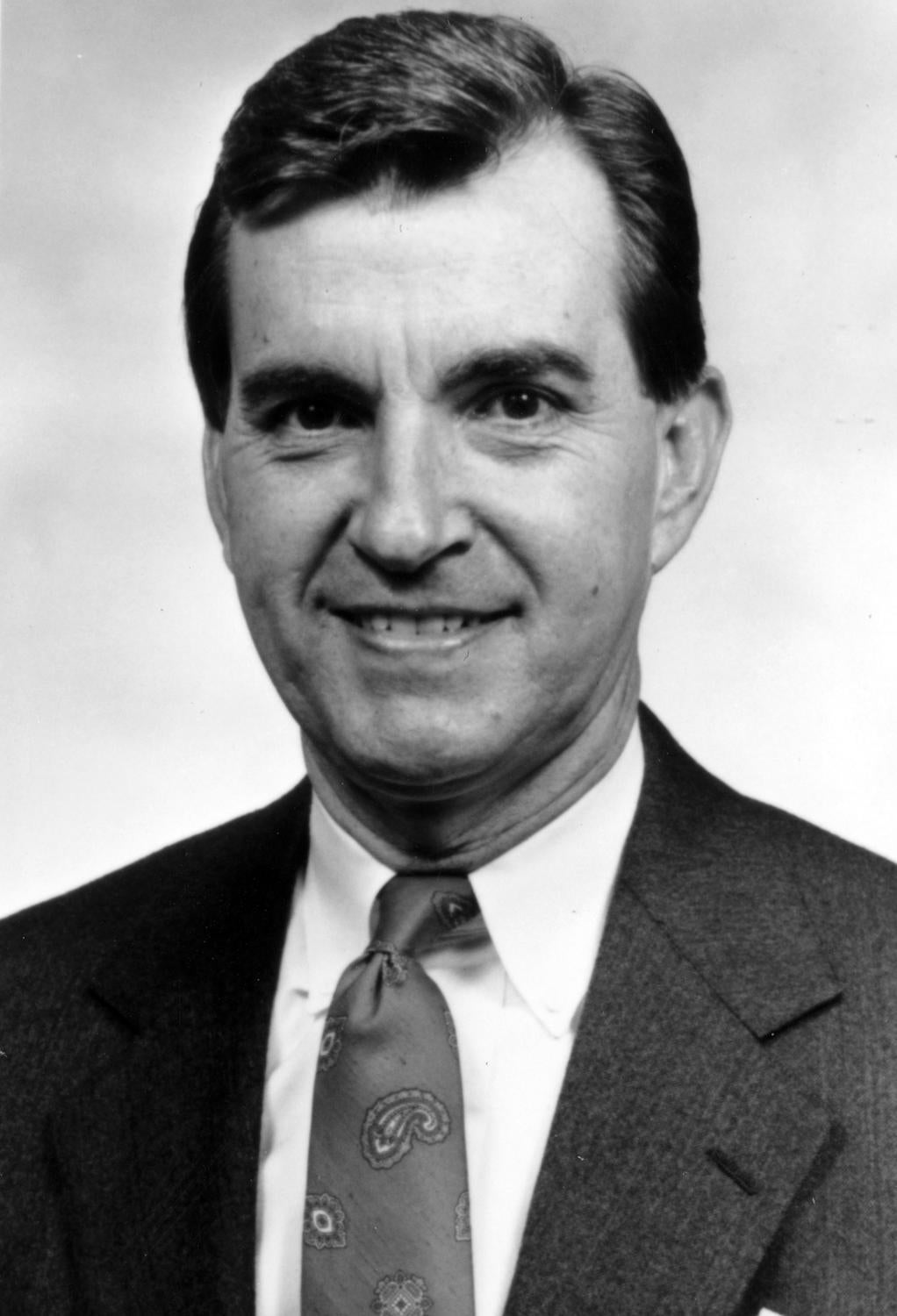

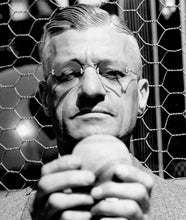

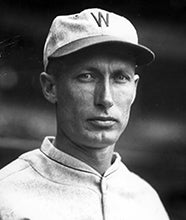

The history of the National Pastime in the nation’s capital cannot be told without acknowledging Clark Griffith, a legendary player, manager and executive whose life in baseball spanned nearly 70 years.

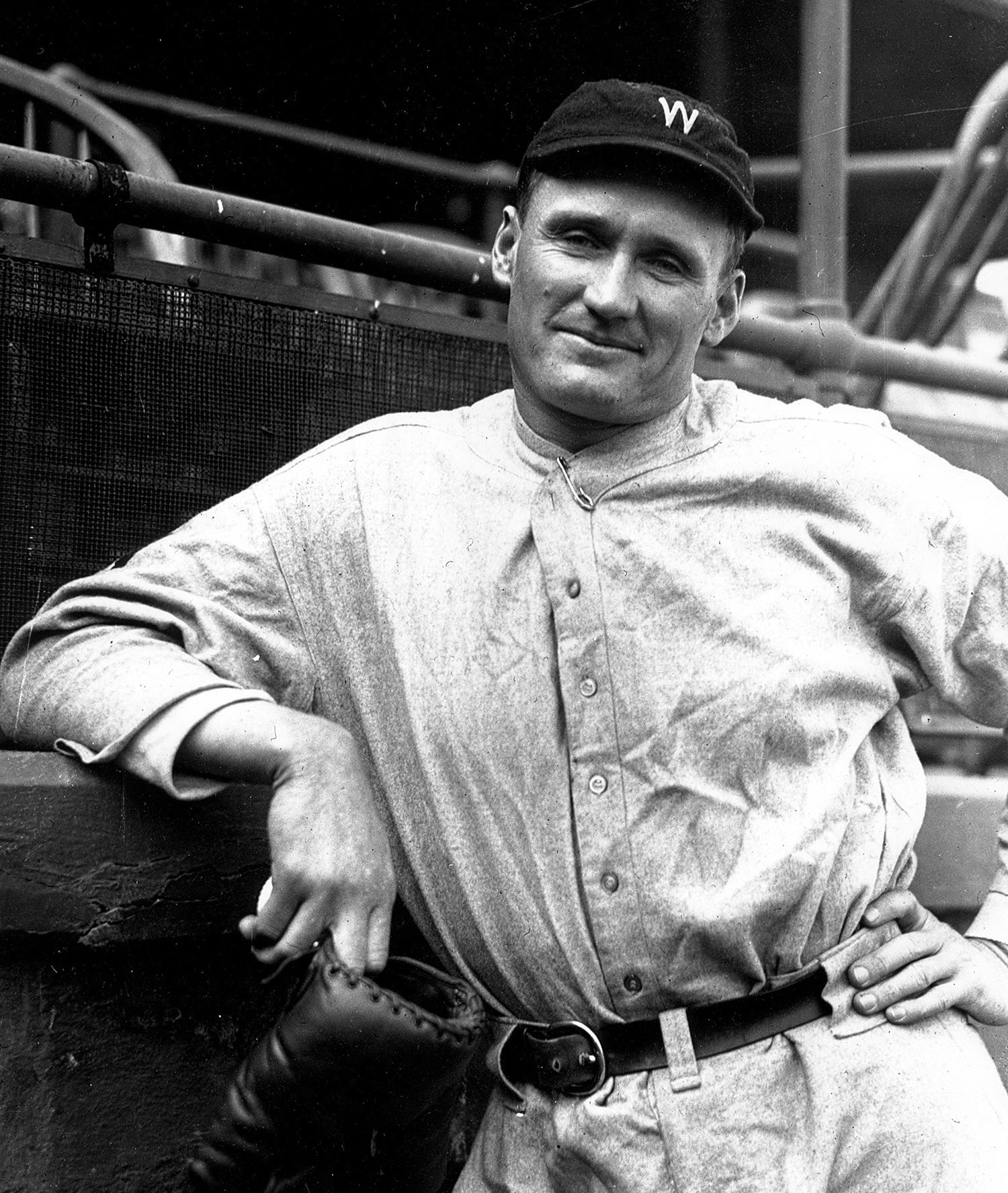

Born to a pioneer family and struck with a chronic illness as a child, Griffith fought his way onto minor league teams as a pitcher. Sporting a frail physique, Griffith relied on guile and masterful control instead of power on the mound, earning himself a nickname as the “Old Fox.”

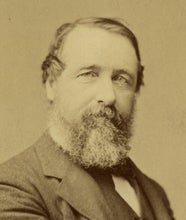

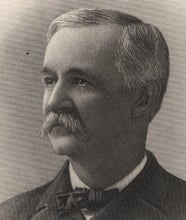

Griffith bounced from league to league and paycheck to paycheck – even performing in Wild West shows to supplement his income – until a fateful meeting with future Hall of Fame executives Charles Comiskey and Ban Johnson gave him his big break. In 1900, Johnson fostered dreams of organizing a league that could challenge the National League at the top ranks of professional baseball. When National League owners rejected a players’ petition for better pay, Griffith pounced on the opportunity by courting many disgruntled players to the new American League.

Griffith served as player-manager for Comiskey’s Chicago White Sox during the AL’s inaugural 1901 season. On the mound, the Old Fox won a league-high 24 games; in the dugout, Griffith captained the White Sox to the league’s first pennant.

“I will hand it unreservedly to [Christy] Mathewson as one of the greatest pitchers who ever lived,” White Sox pitcher Jimmy Callahan later said. “But I think that old Clark Griffith, in his prime, was cagier; a more crafty, if not a more brainy, proposition.”

In 1903, Johnson moved the Baltimore Orioles franchise to New York and renamed them the Highlanders. He appointed Griffith as manager for the team who would eventually become the Yankees. Griffith managed the Highlanders for six seasons before crossing over to the NL’s Cincinnati Reds. Three years later, Griffith began his most famous tenure as manager of the AL’s Washington Senators.

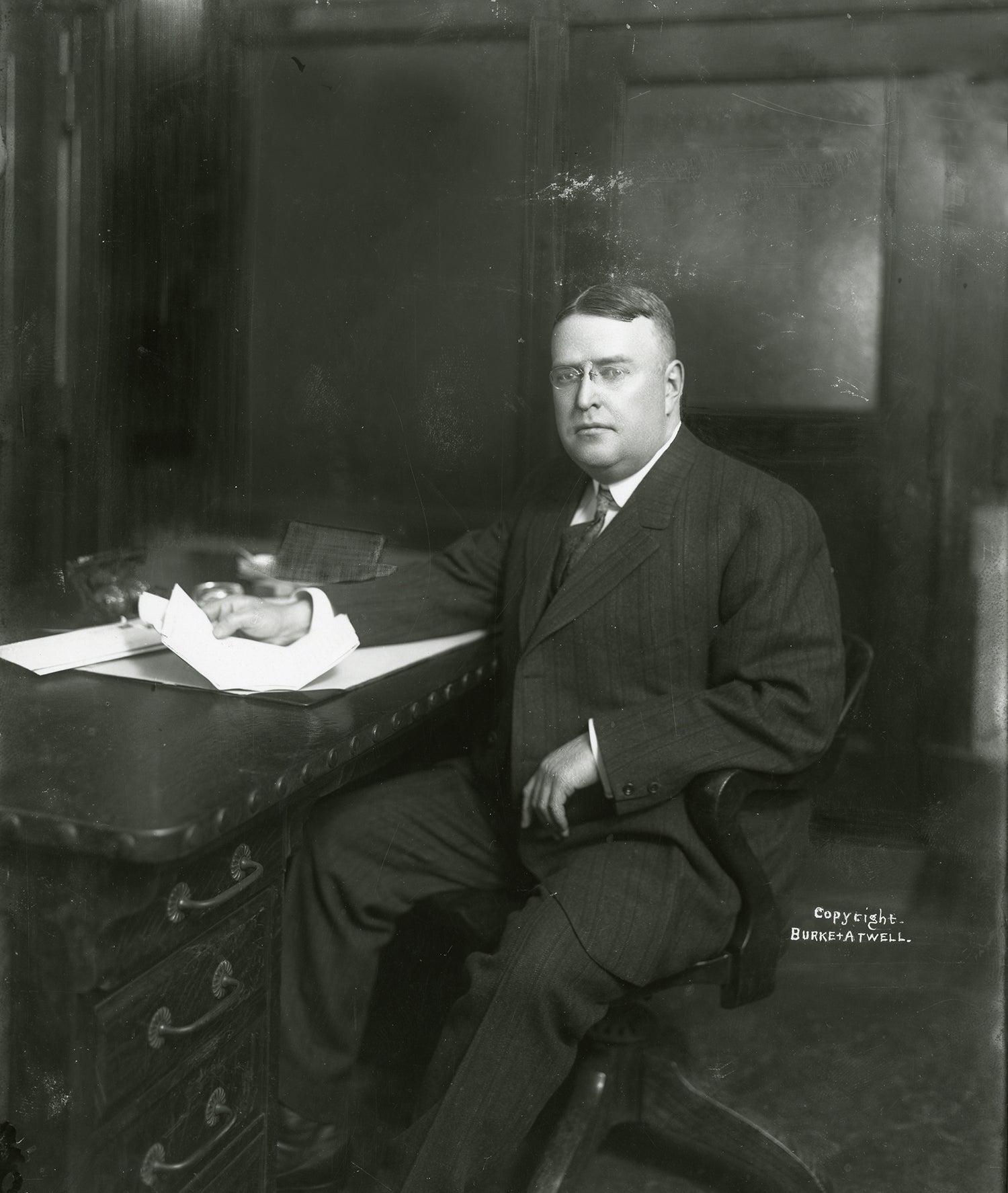

After failing to secure loans from Comiskey and Johnson, in 1912 Griffith mortgaged nearly all of his assets to purchase a 10 percent ownership stake in a Senators club that had never finished above sixth place. Griffith immediately released and traded many of the team’s veterans, and most sportswriters picked the Senators to finish in the league’s second division yet again. However, thanks to a 17-game winning streak and 33 victories from Hall of Fame pitcher Walter Johnson, Washington posted its best season in history with a second-place finish.

“Every baseball fan knows the parody about Washington: First in war; first in peace, and last in the American League,” Griffith said. “But I had enough confidence in myself to think that I could pull out that club, rebuild it, and make it a winner – and therefore a big money maker.”

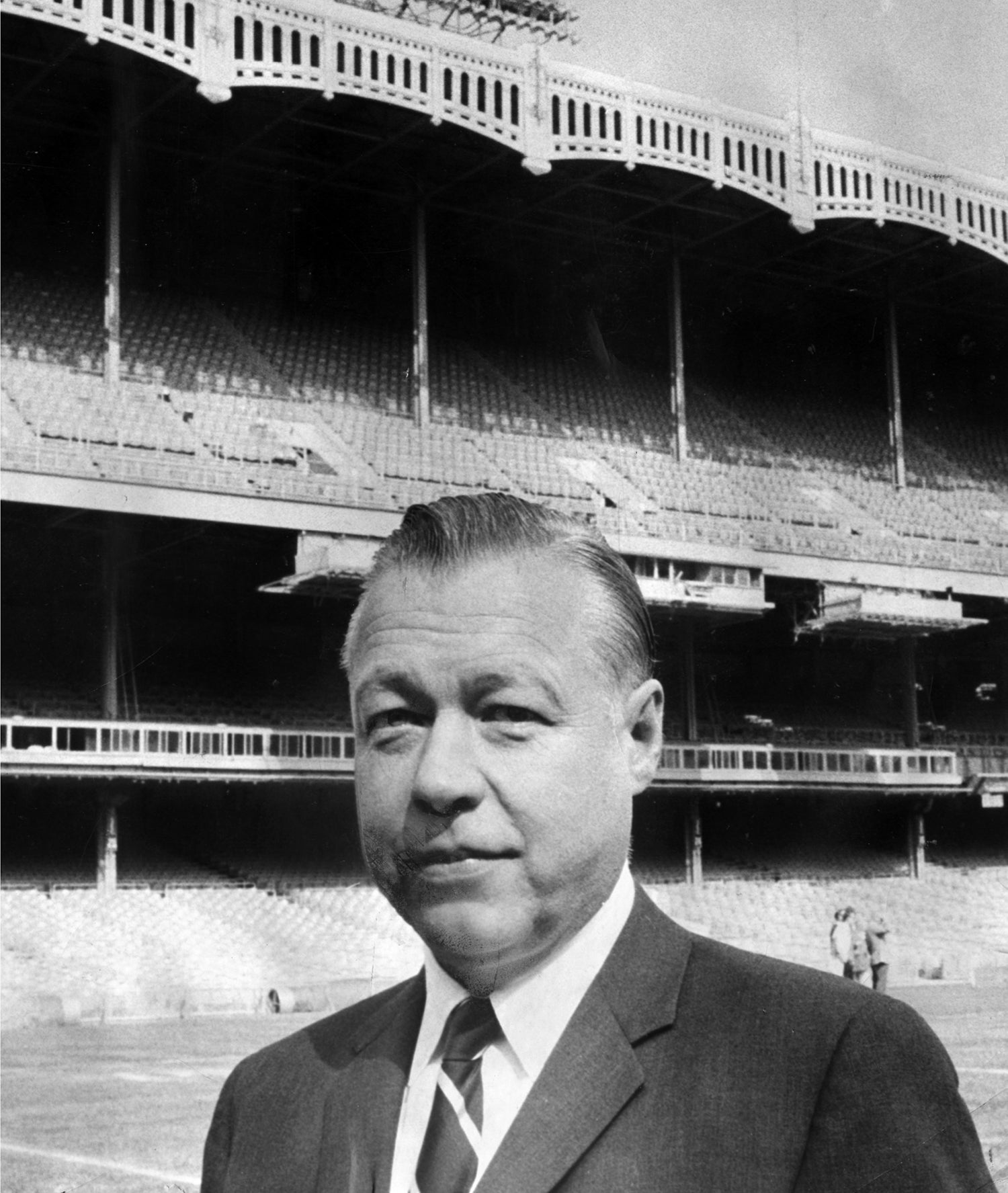

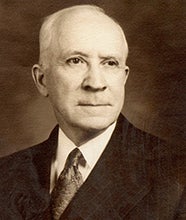

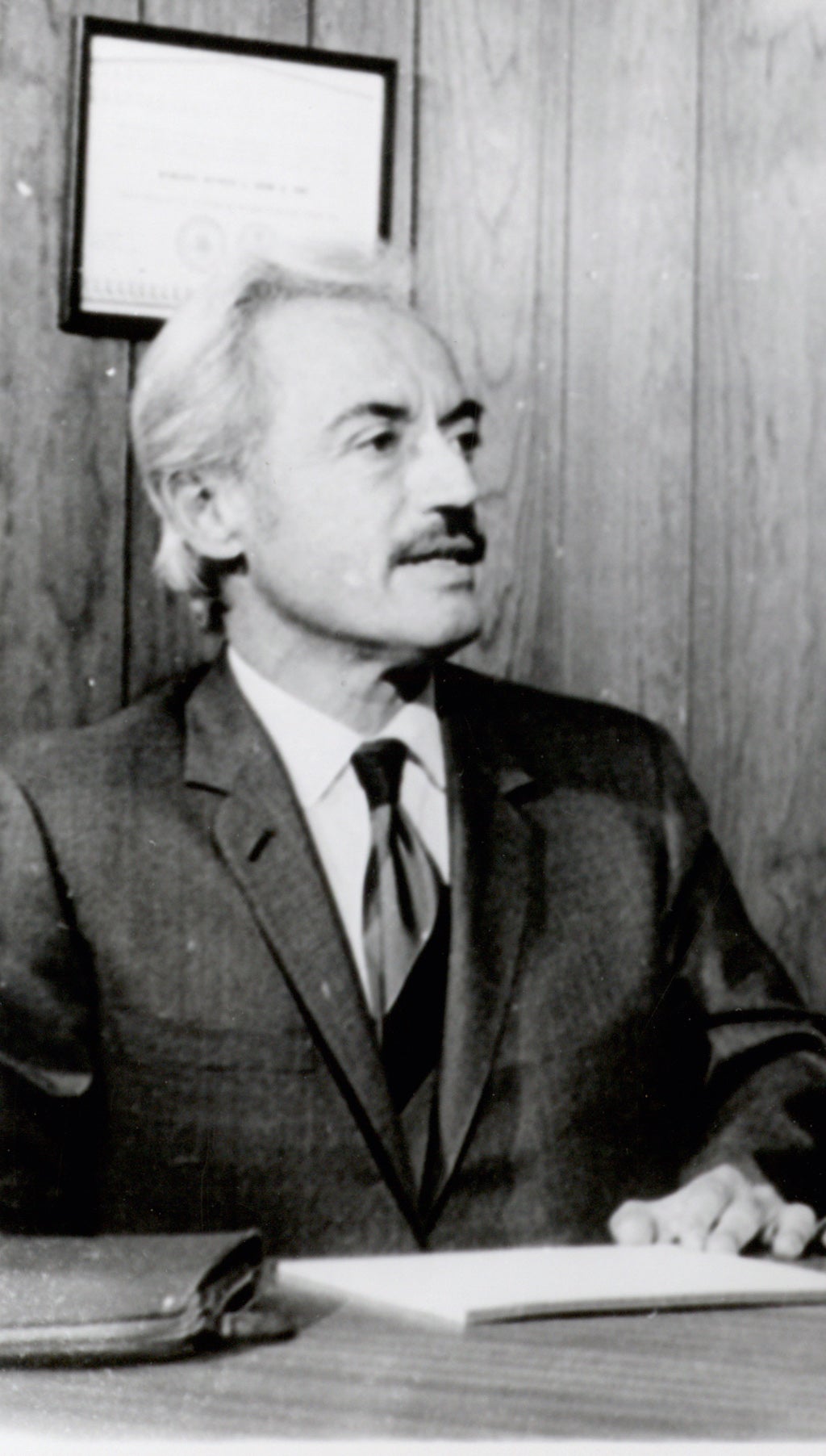

Griffith skippered the Senators to five first-division finishes in nine seasons before mortgaging his Montana ranch once again to buy a majority share of the team. By 1920, Griffith had moved upstairs to the owner’s box, ending a 20-year managerial career in which he won 1,491 games. That same year, the team’s National Park was renamed in his honor, further cementing his role as the patriarch of Washington baseball.

“He was a wonderful man, always helpful and kind,” said Hall of Famer Goose Goslin. “He wasn't like a boss, more like a father. He was more than a father to me, that man.”

It was in that owner’s box that Griffith established a reputation as one of the shrewdest roster builders in the game. He had no income outside of the Senators and often had to run his franchise on a shoestring budget. However, the Senators were able to turn a profit for 21 consecutive years, thanks in large part to hosting football games, Negro League games and many other special events at Griffith Stadium.

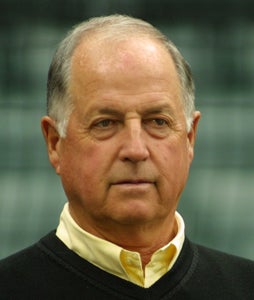

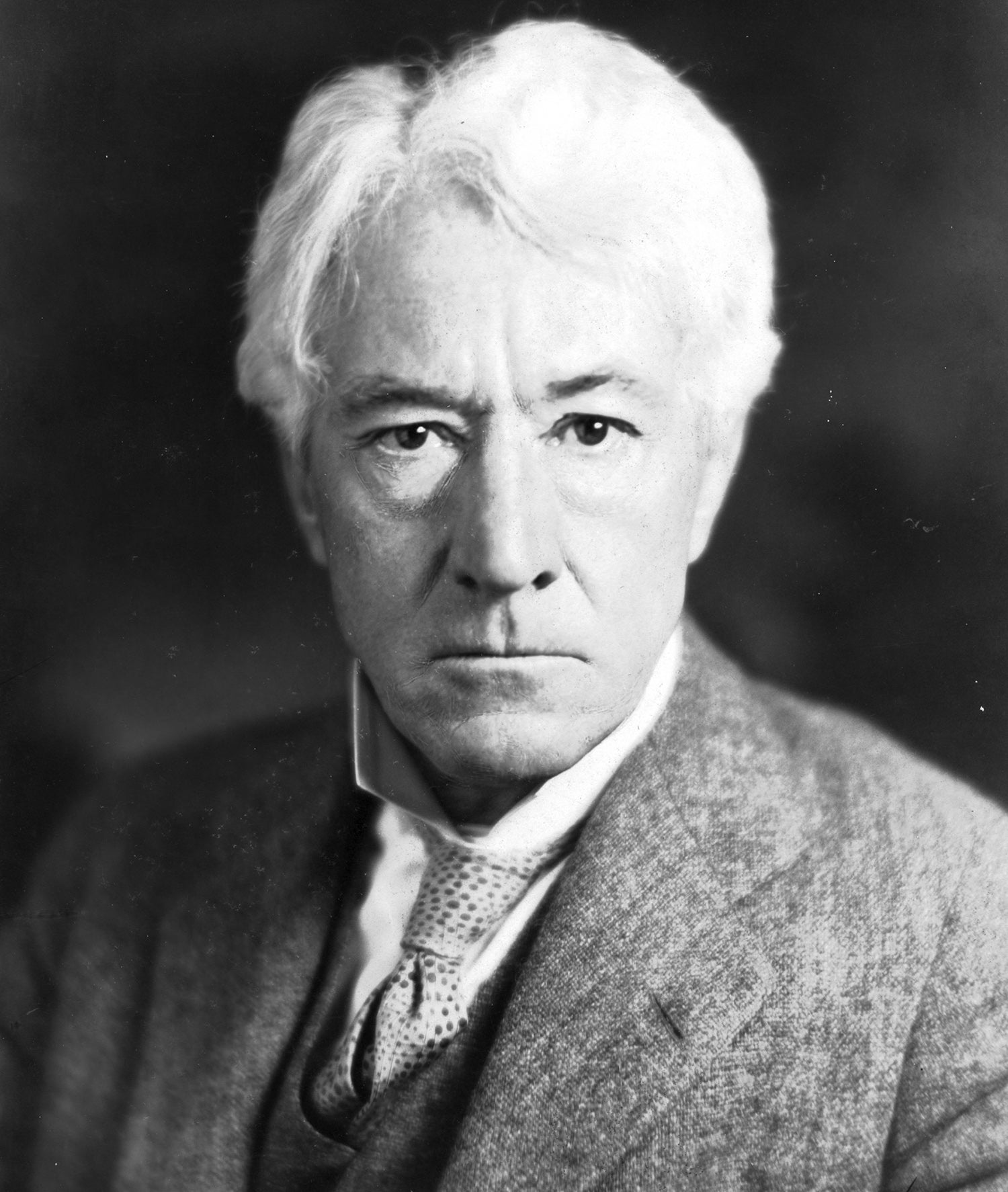

In 1924, Griffith hired 27-year-old Bucky Harris to be his manager and assembled the “cheapest championship team of all-time,” according to The New York Times. Featuring a roster of young stars including Johnson, Goslin, Joe Judge, Ossie Bluege and Sam Rice, Griffith’s Senators shocked the world by beating the New York Giants in the World Series. Washington then followed up with two more pennants in 1925 and 1933.

“Of all the 10,000 afternoons I have spent in a ball park during the last 55 years as a player, manager and club owner, that afternoon is my pet,” Griffith said of the day the Senators won their only Fall Classic. “I was so all-fired excited, I forgot that Calvin Coolidge was my guest.”

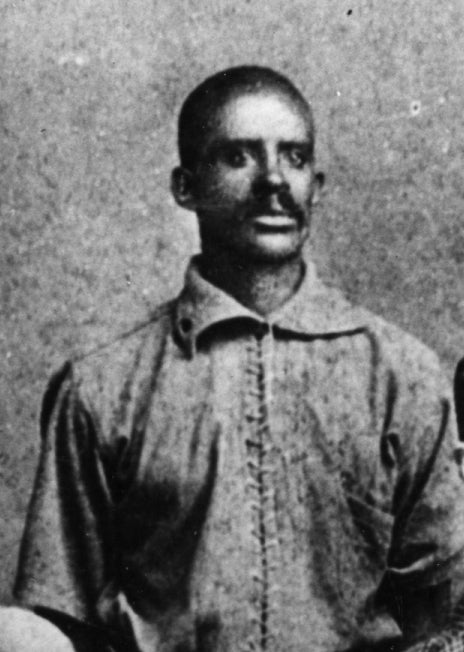

Off the field, Griffith became known as an advocate for Latin American players – particularly those from Cuba. During Griffith’s 44 years as manager and owner in Washington, D.C., 35 Cuban players broke into the major leagues with the Senators.

Griffith was also known for his desire to entertain the fans. As manager, he hired coaches Nick Altrock and Al Schacht to perform comedy routines on the field between innings. He was also friends with eight U.S. presidents and began a longtime tradition by asking President William Howard Taft to throw out the ceremonial first pitch in 1910.

Griffith continued as the Senators’ team president until his passing on Oct. 27, 1955. He remains the only man in major league history to have been a professional player, manager and owner for at least 20 years apiece.

Griffith was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1946.

“He was the greatest humanitarian who ever lived, and the greatest pillar of honesty ever had,” said pitcher Bobo Newsom. “I never played for a better man.”