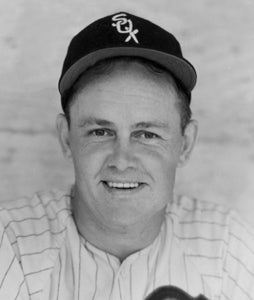

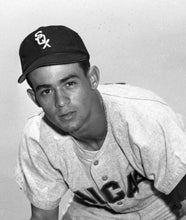

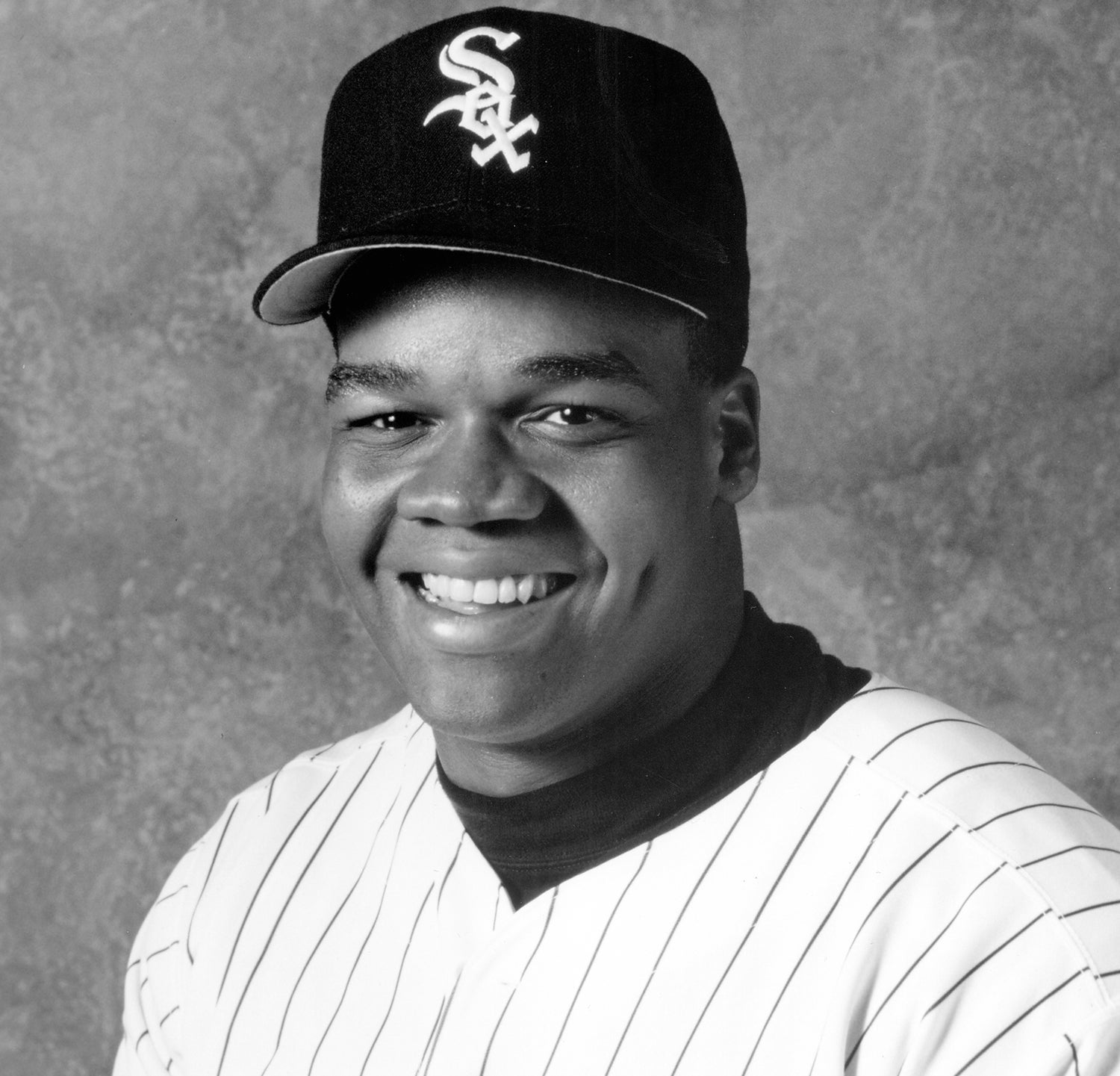

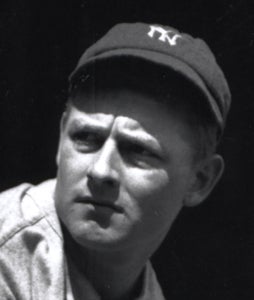

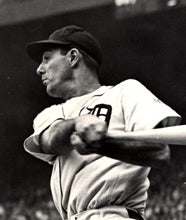

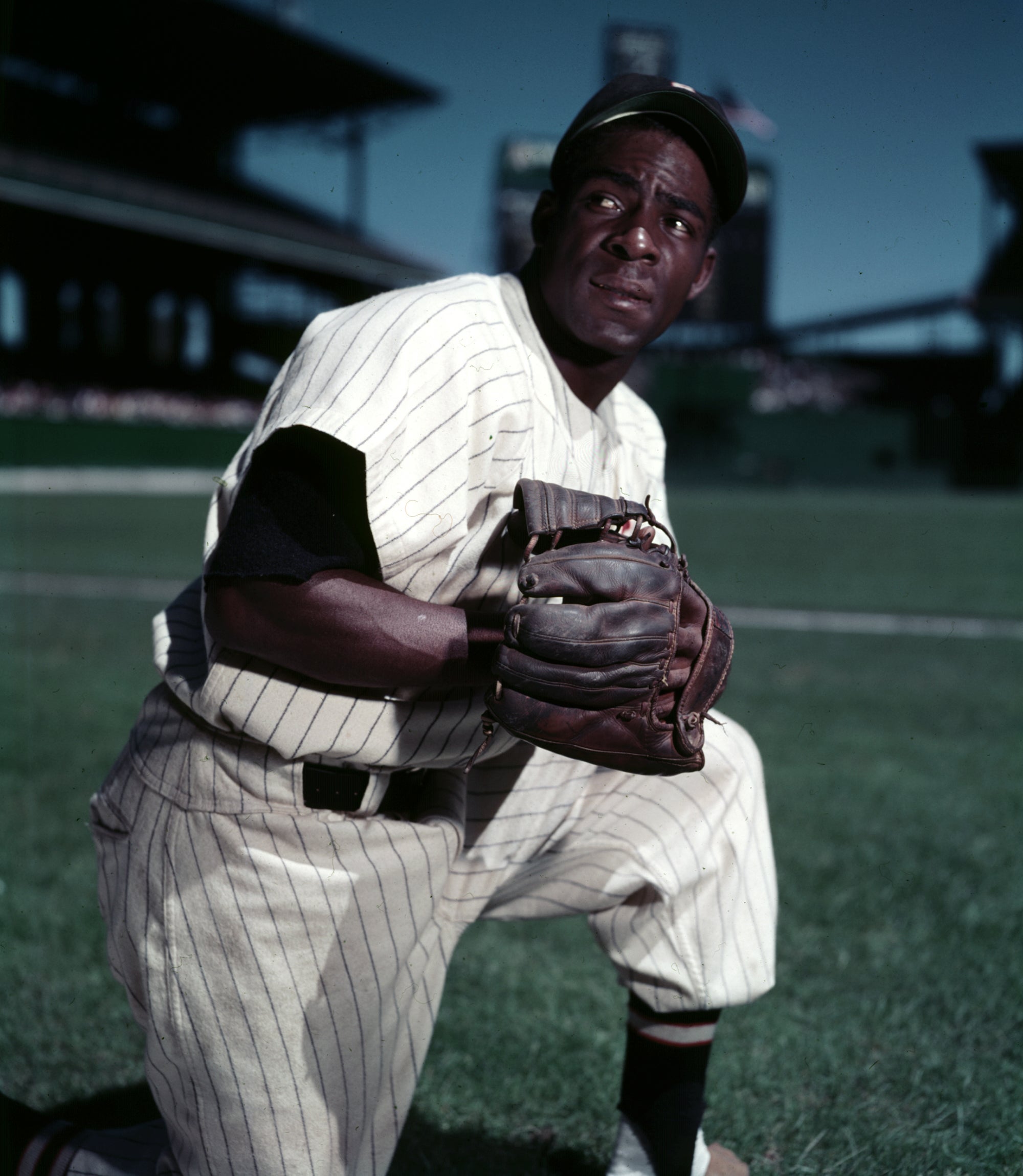

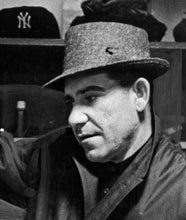

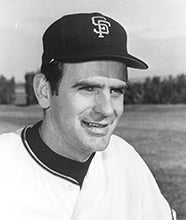

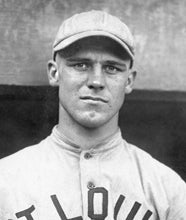

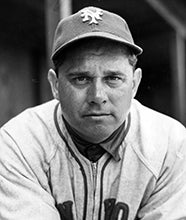

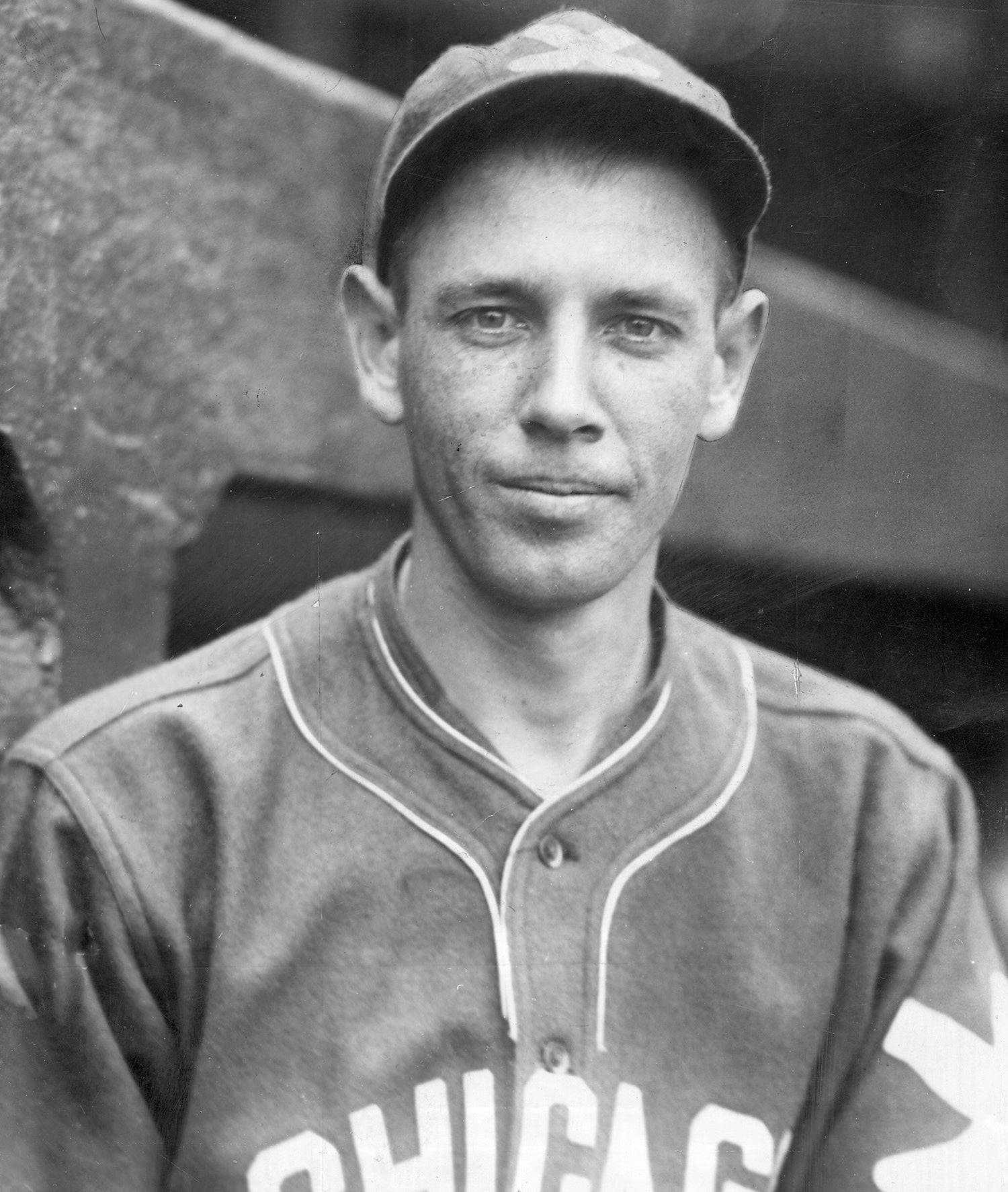

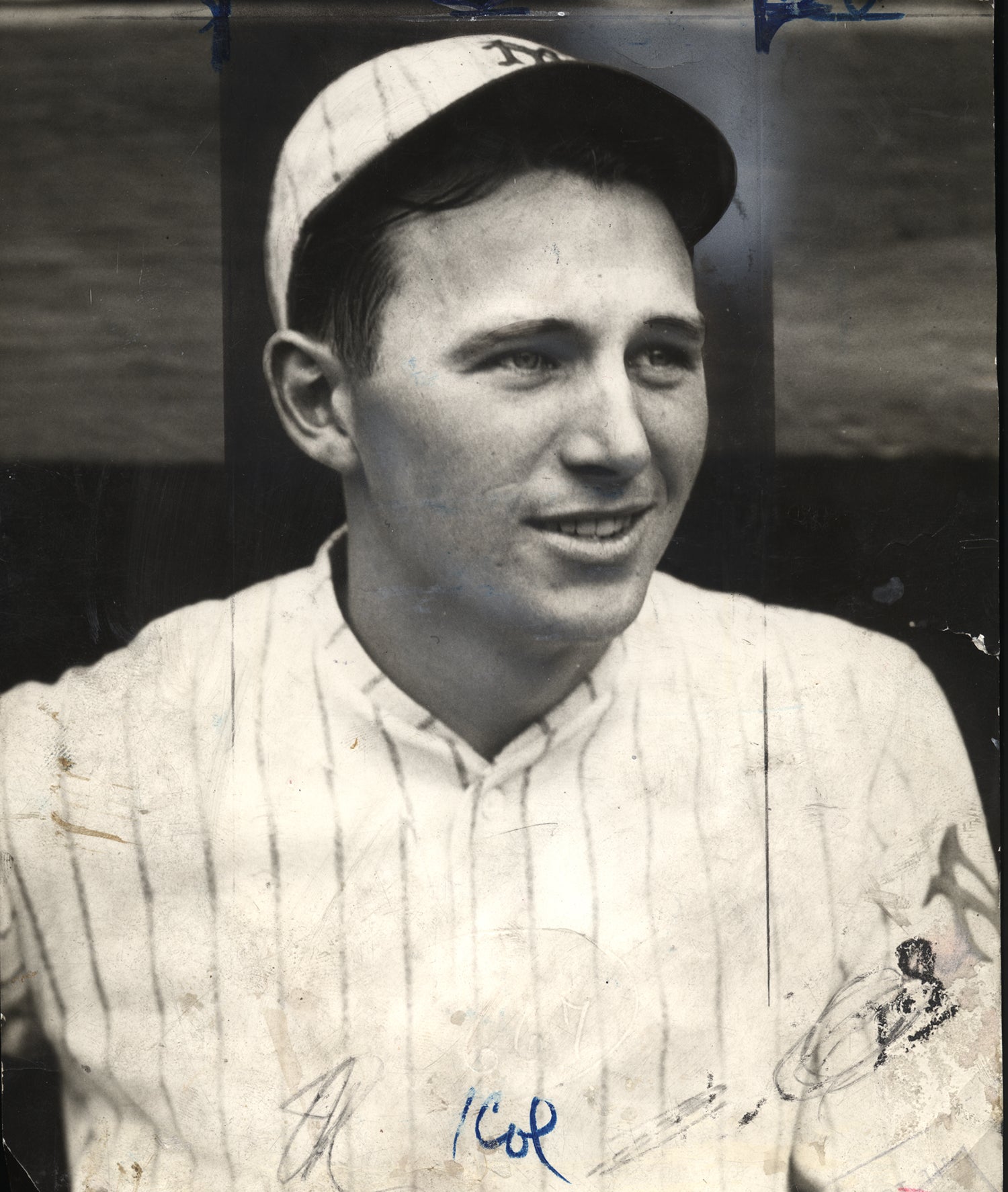

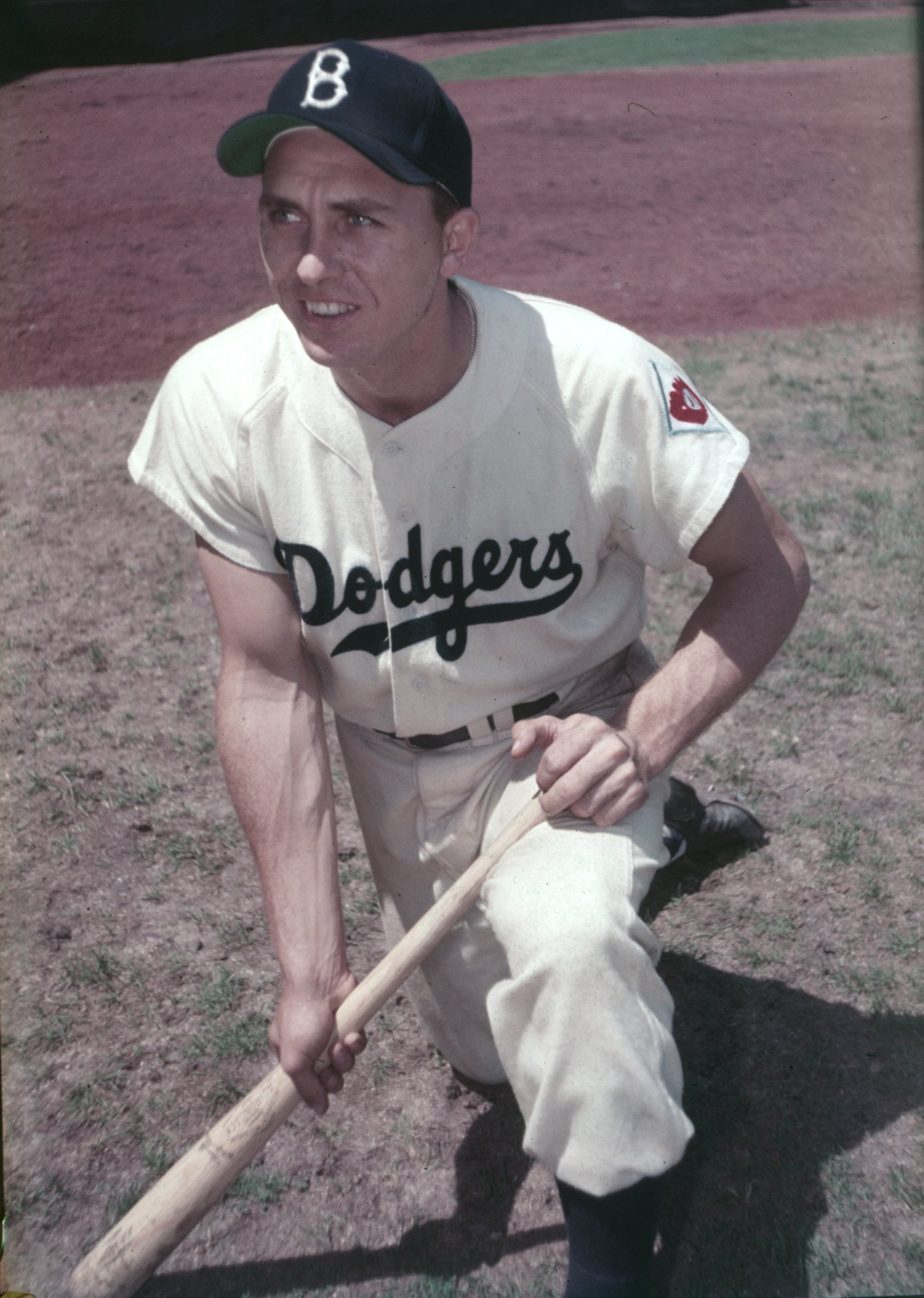

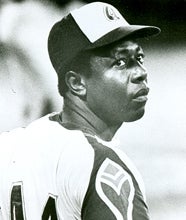

For fans of modern baseball, it was Luis Aparicio who heralded in a new era of base stealing in the 1950s, an era that was soon punctuated by the feats of Maury Wills, who broke Ty Cobb’s single season record in 1962.

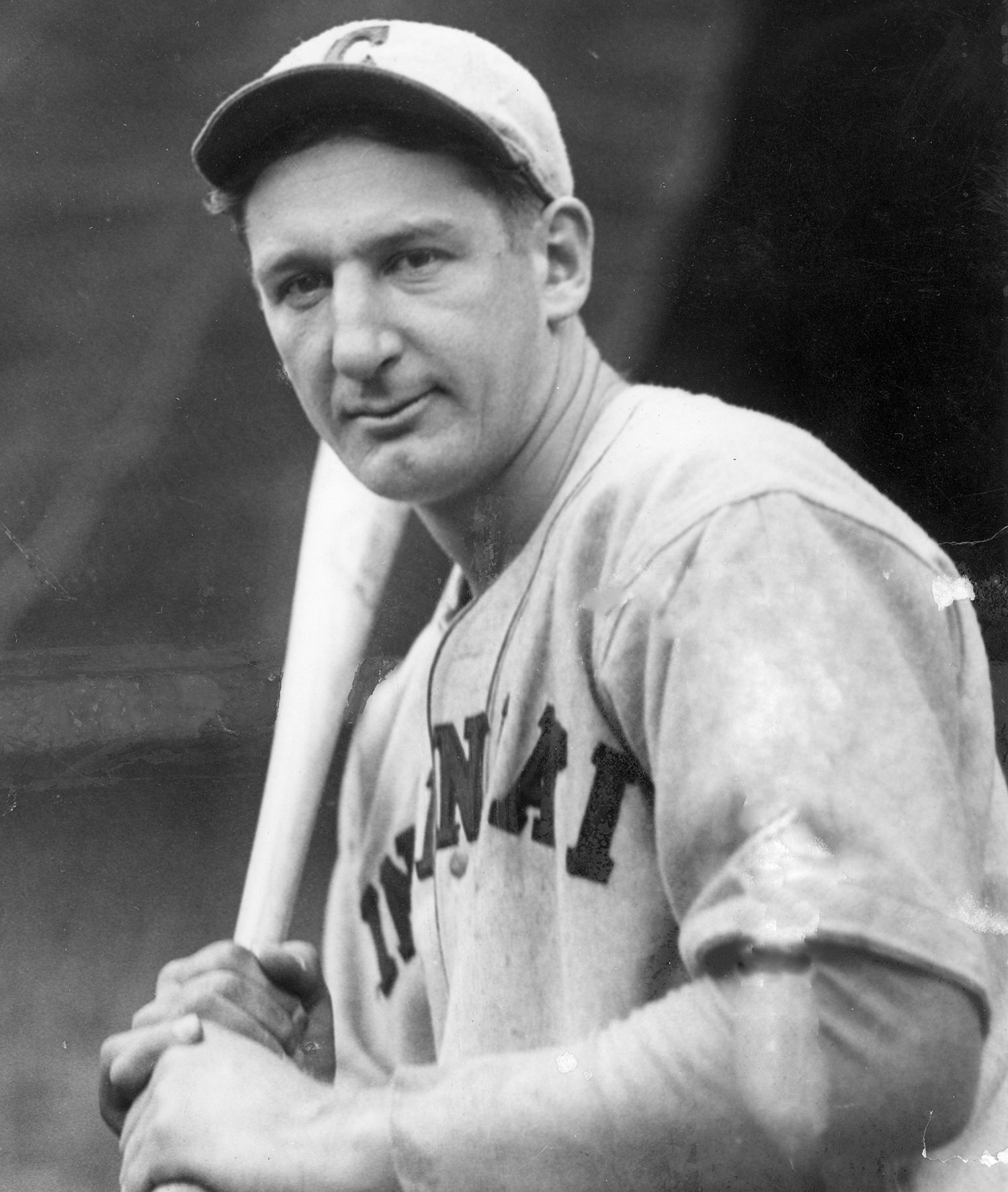

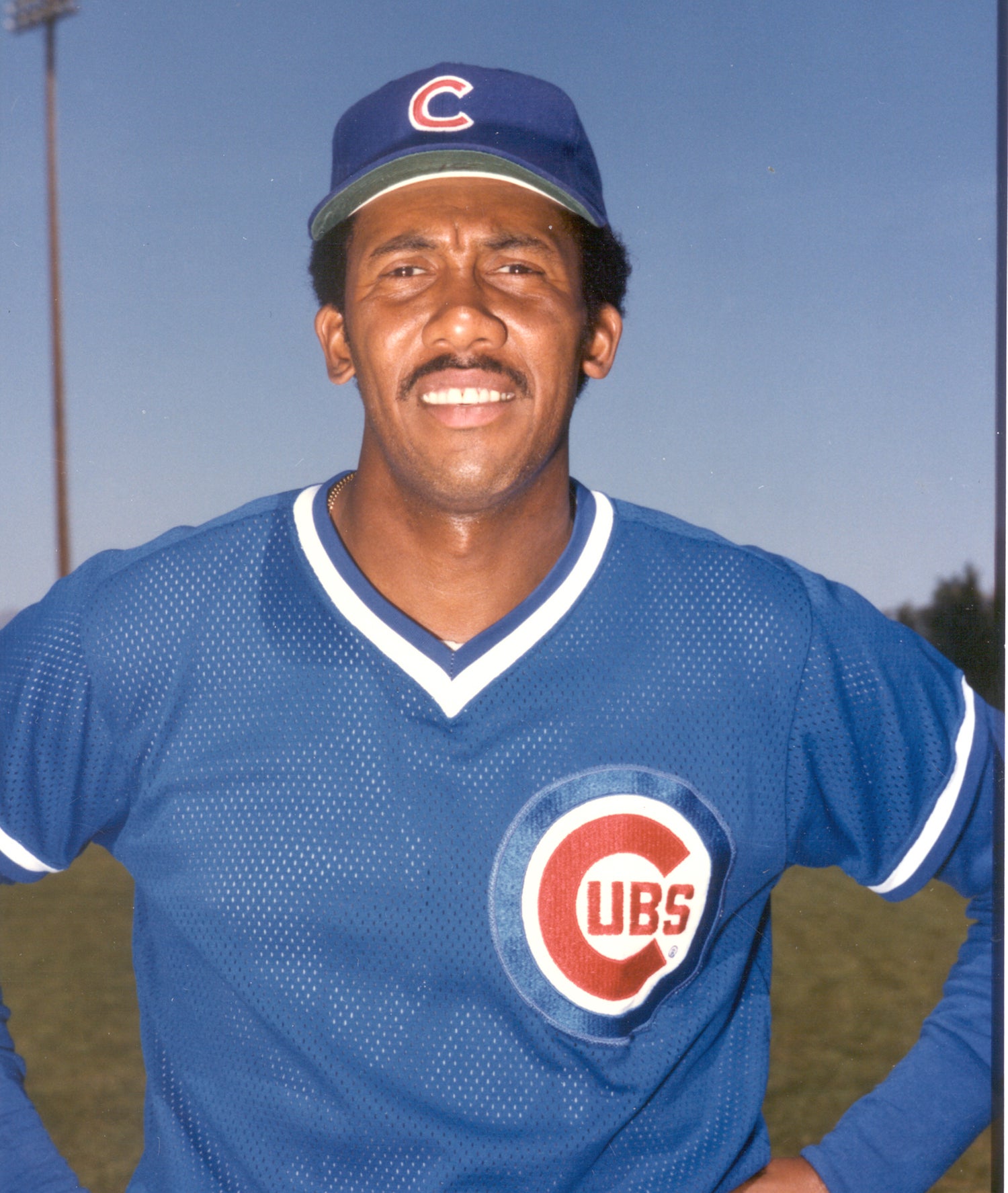

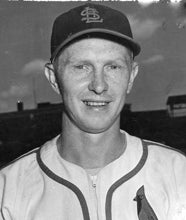

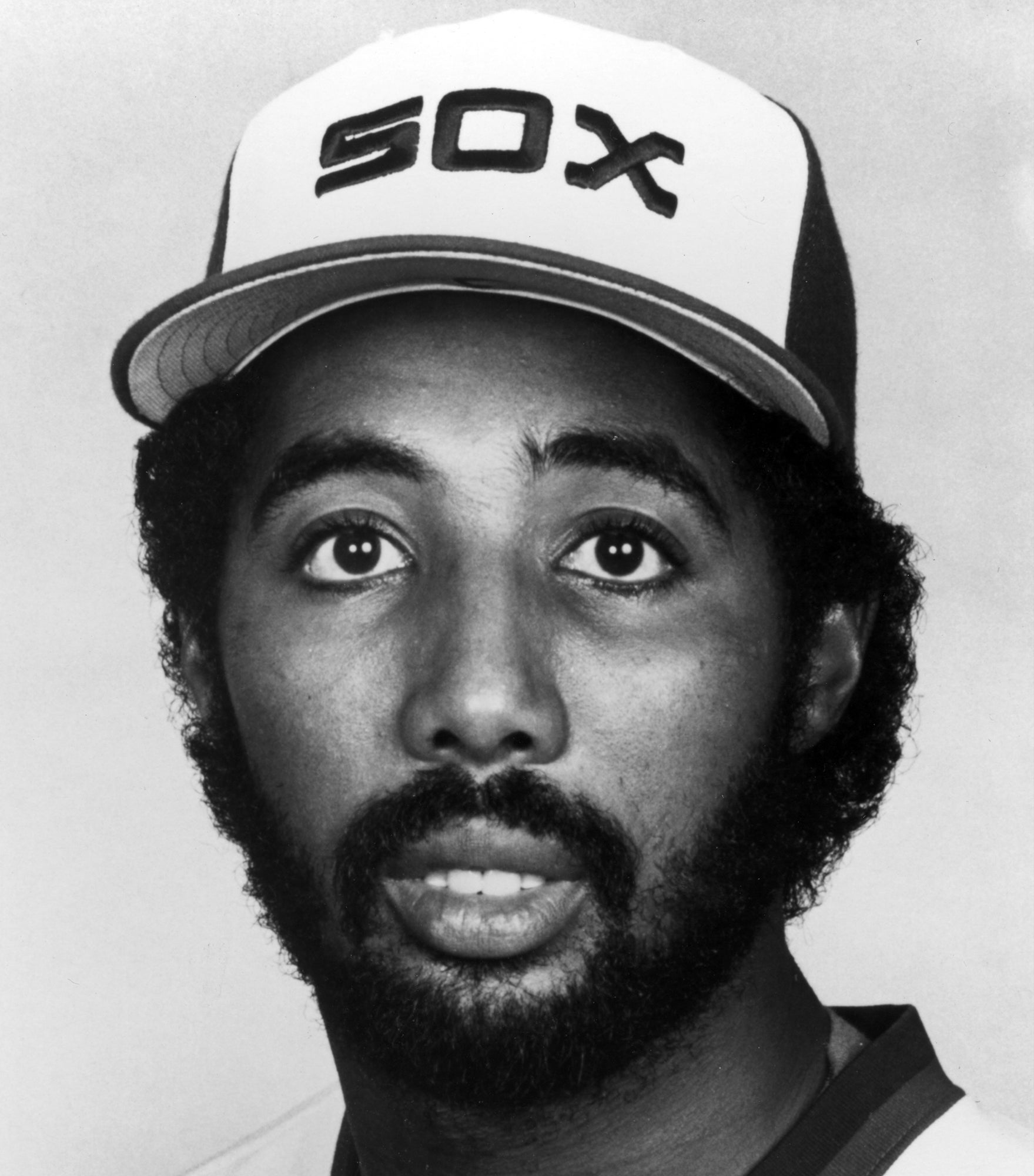

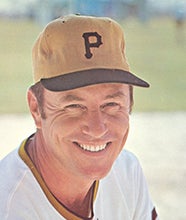

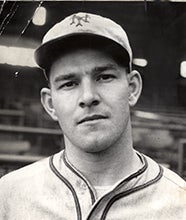

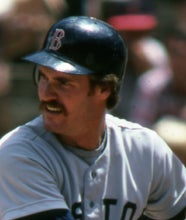

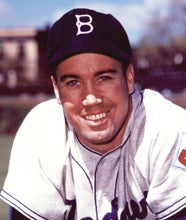

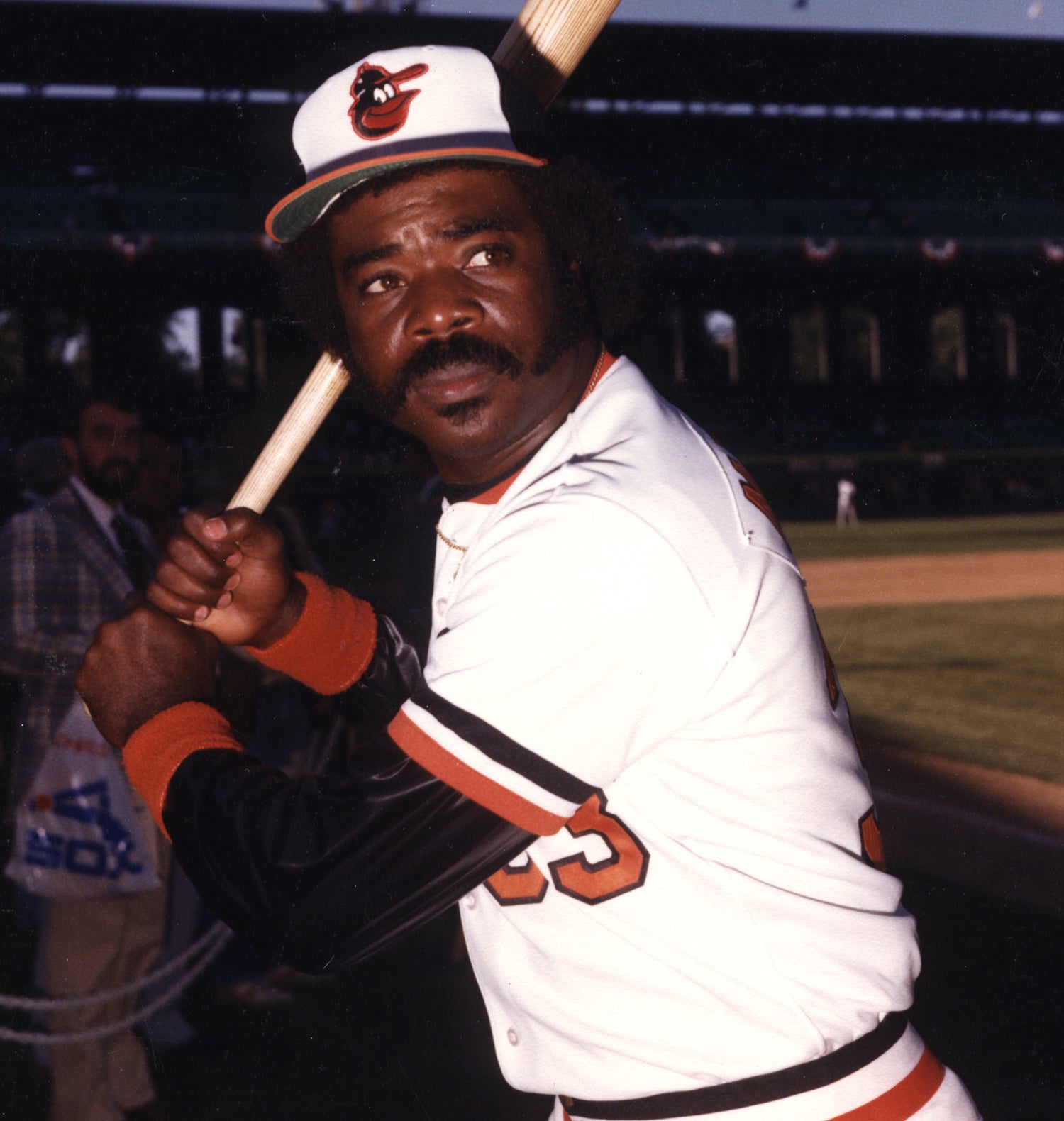

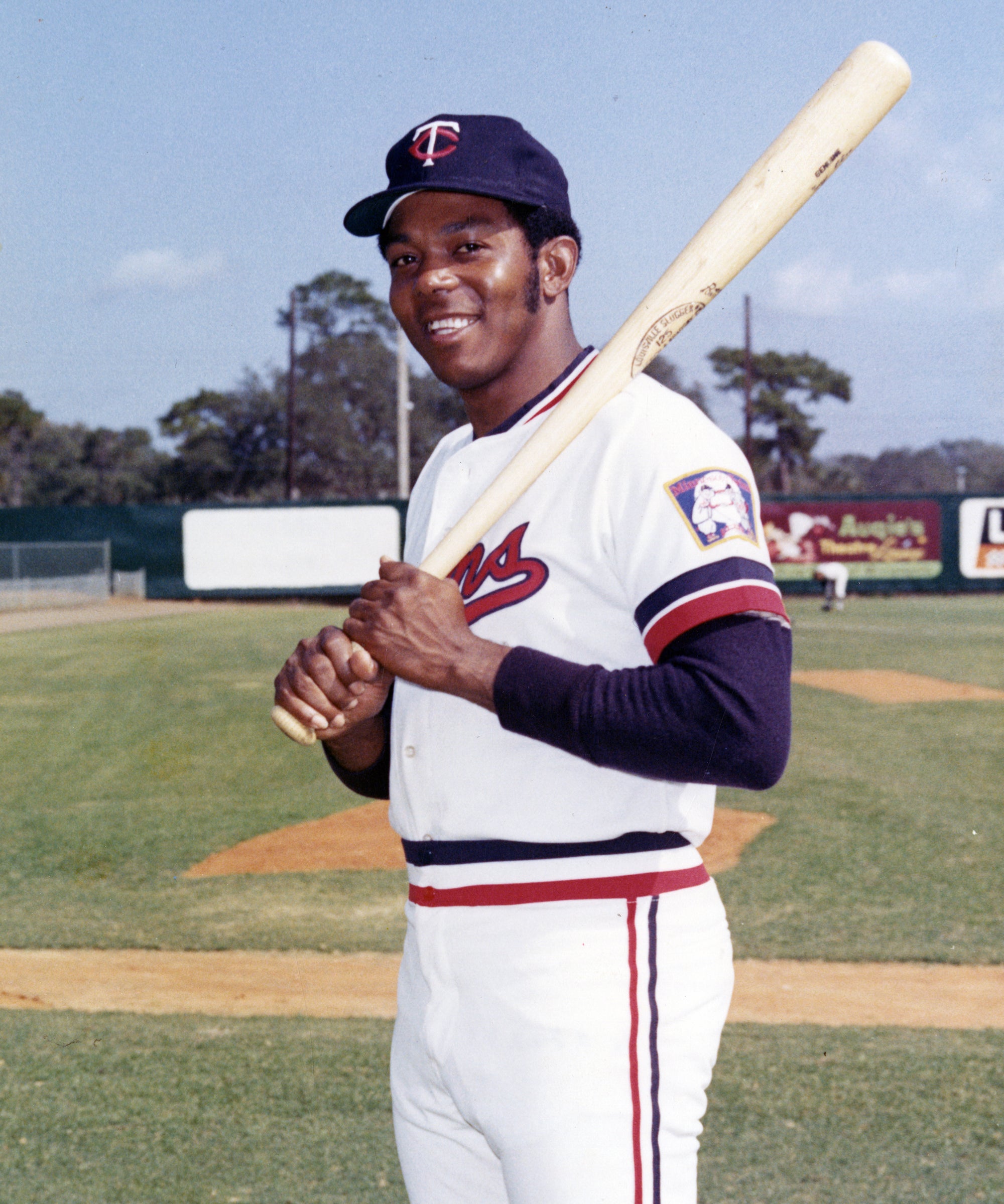

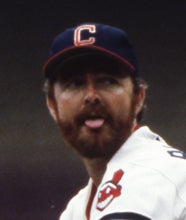

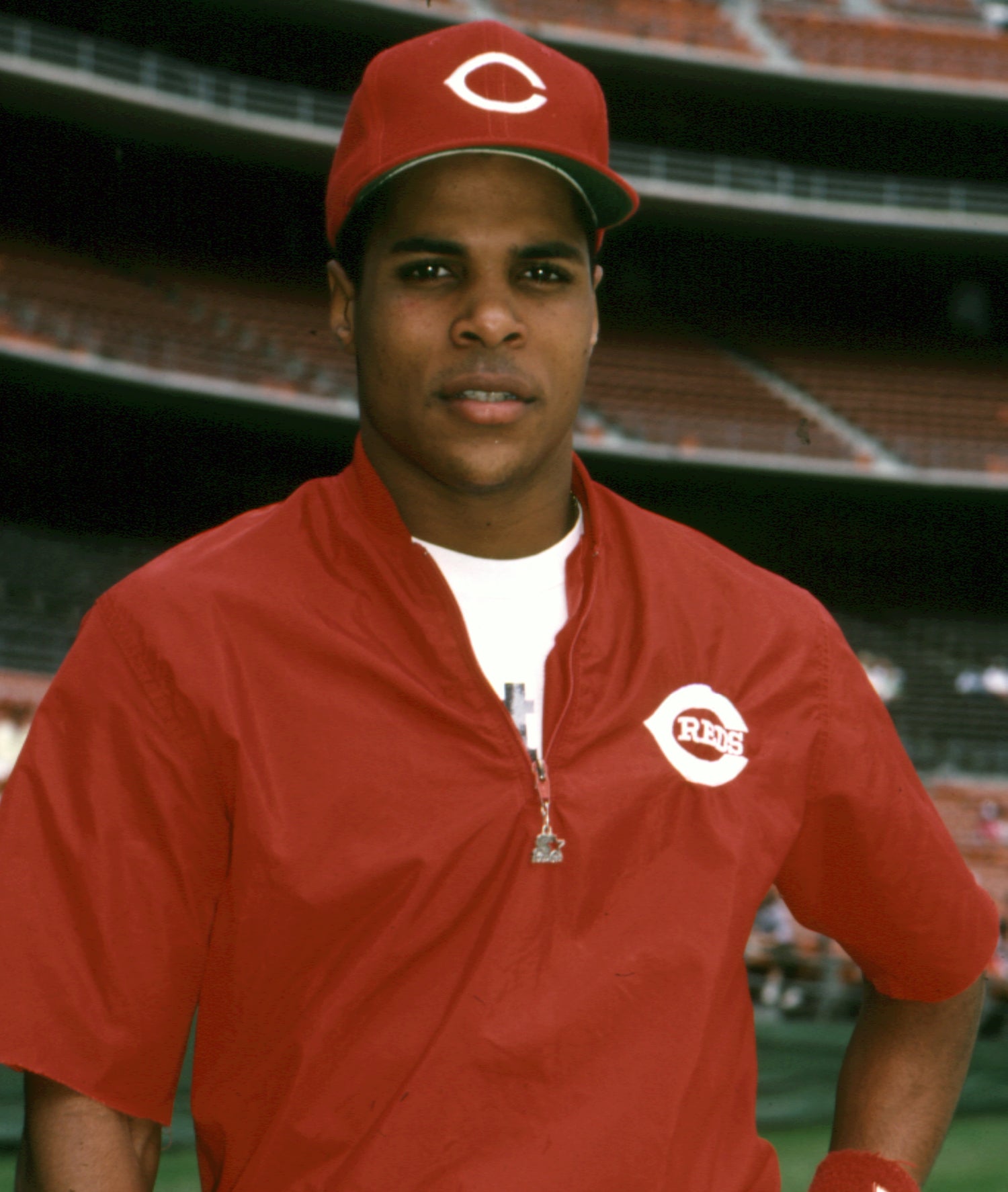

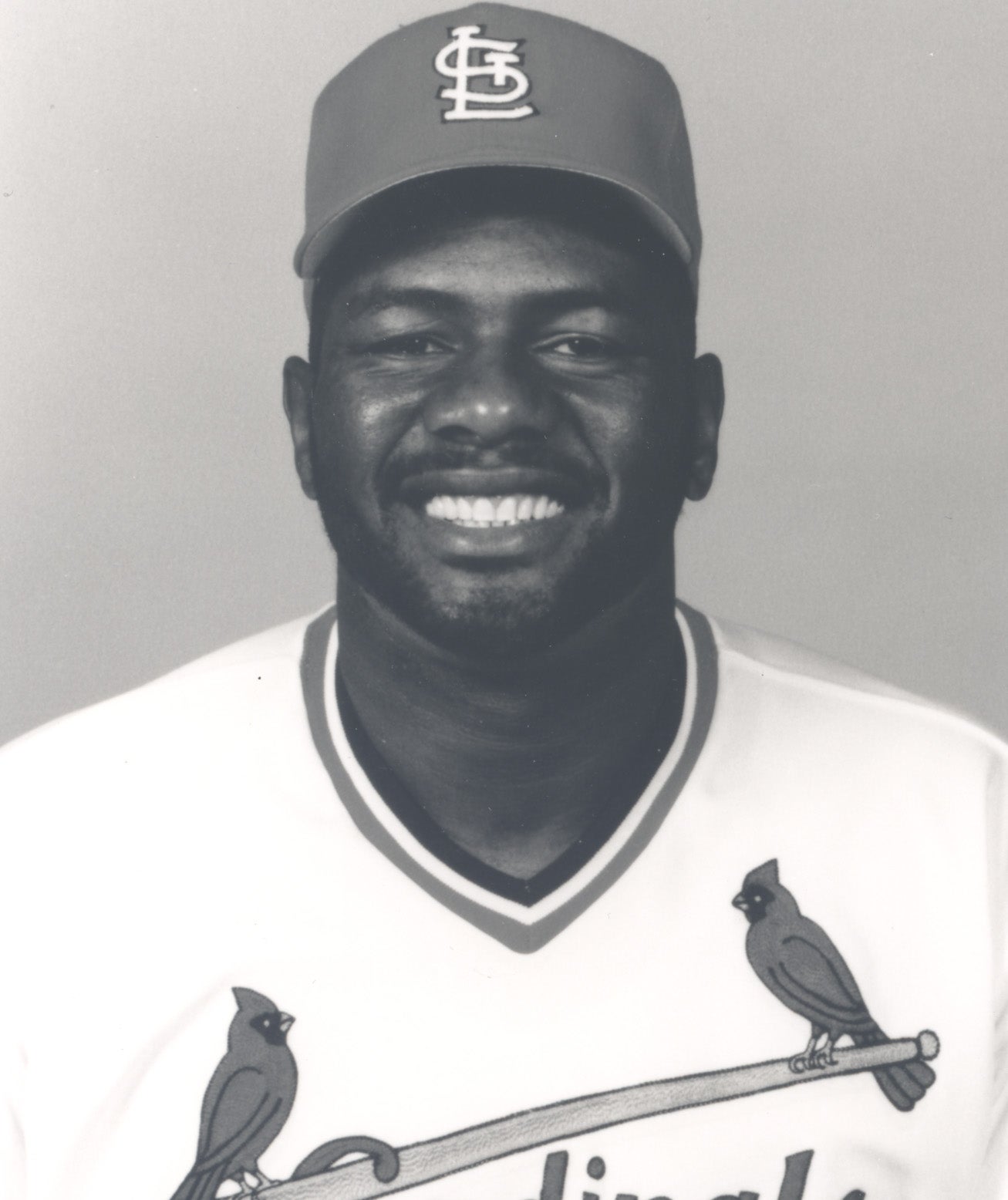

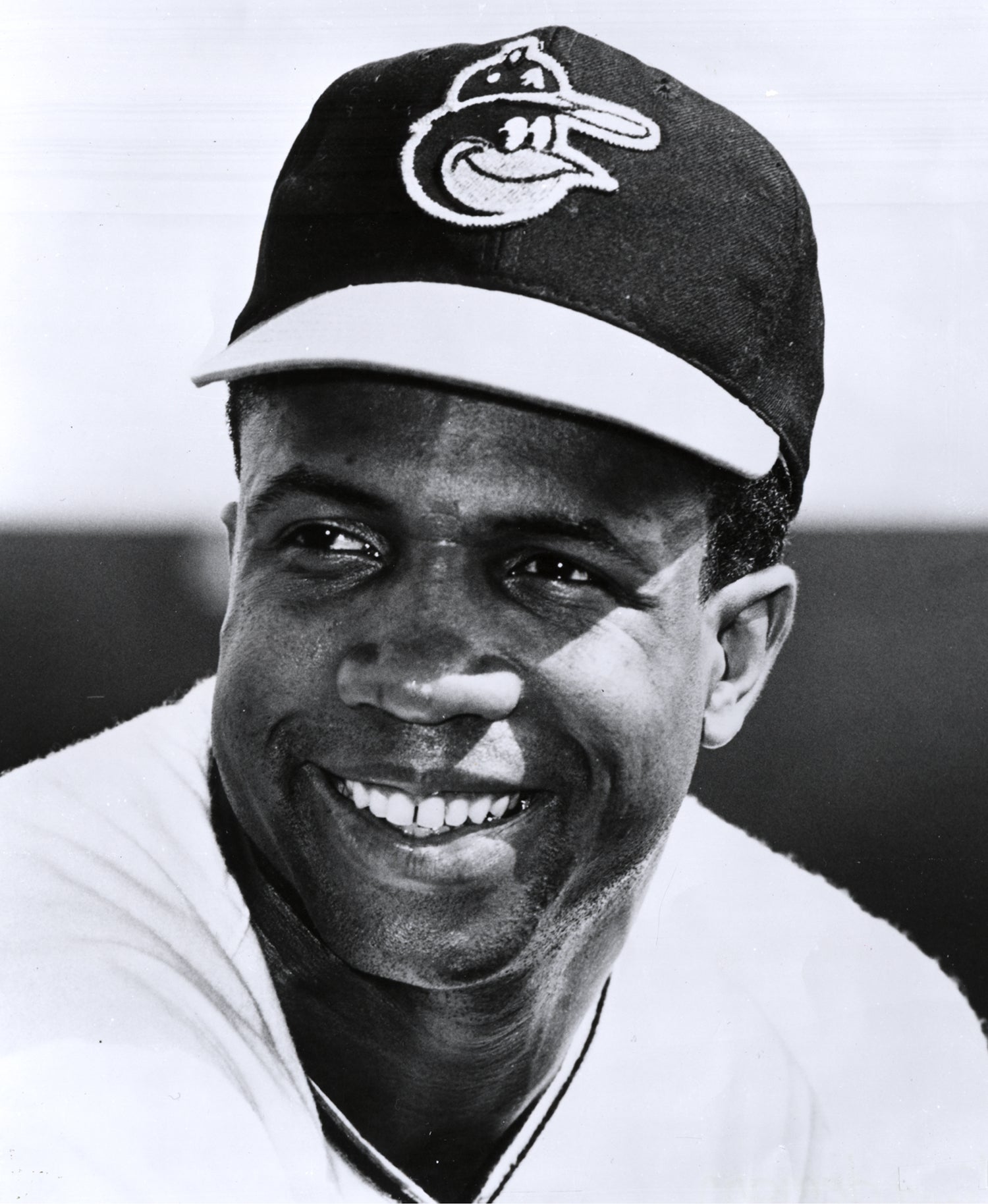

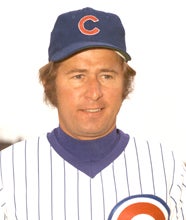

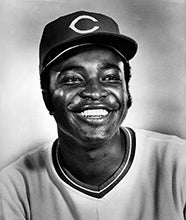

Cobb had the long-standing career mark of 892, which seemed unapproachable until Lou Brock came along. Brock surpassed Cobb’s career total in 1977, 16 years after The Georgia Peach’s death.

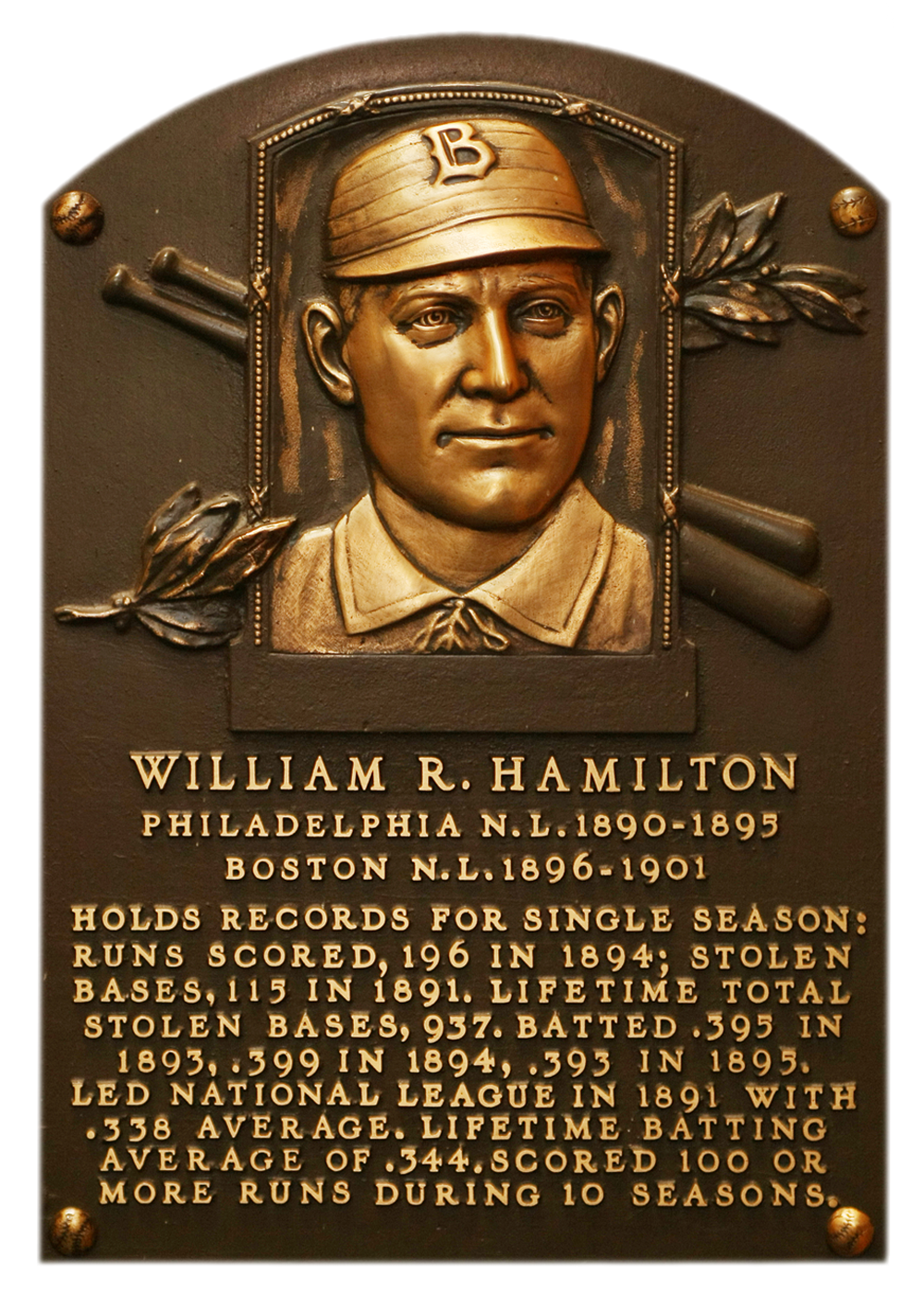

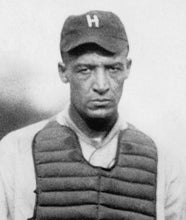

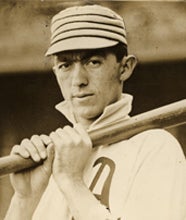

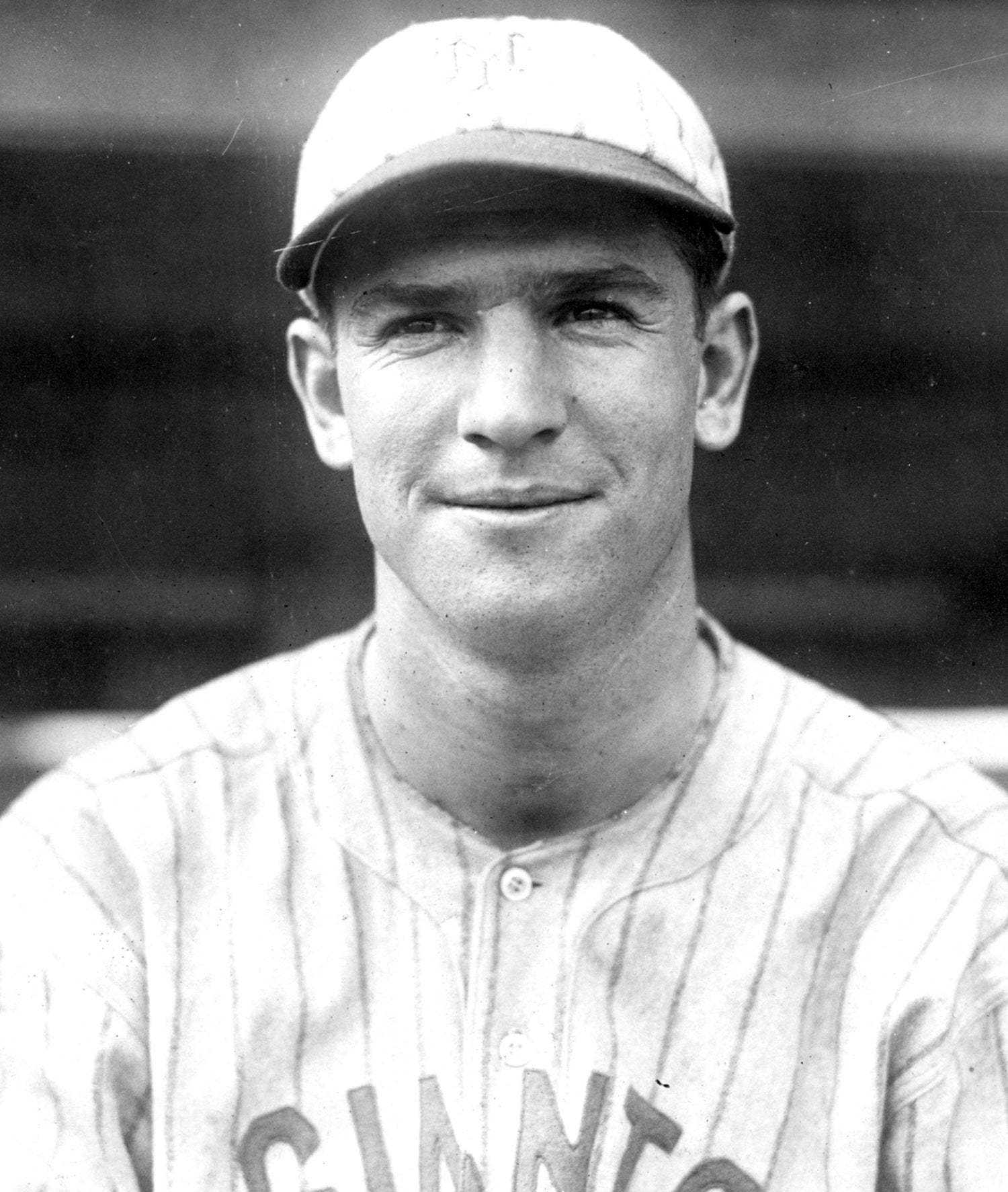

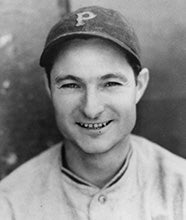

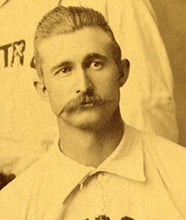

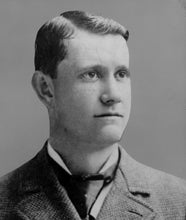

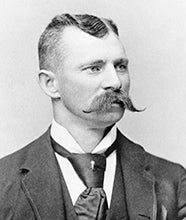

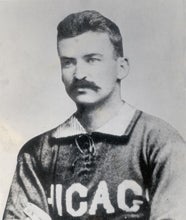

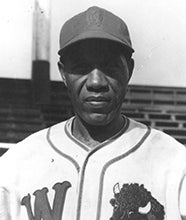

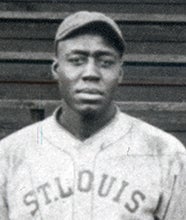

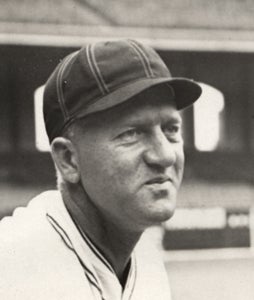

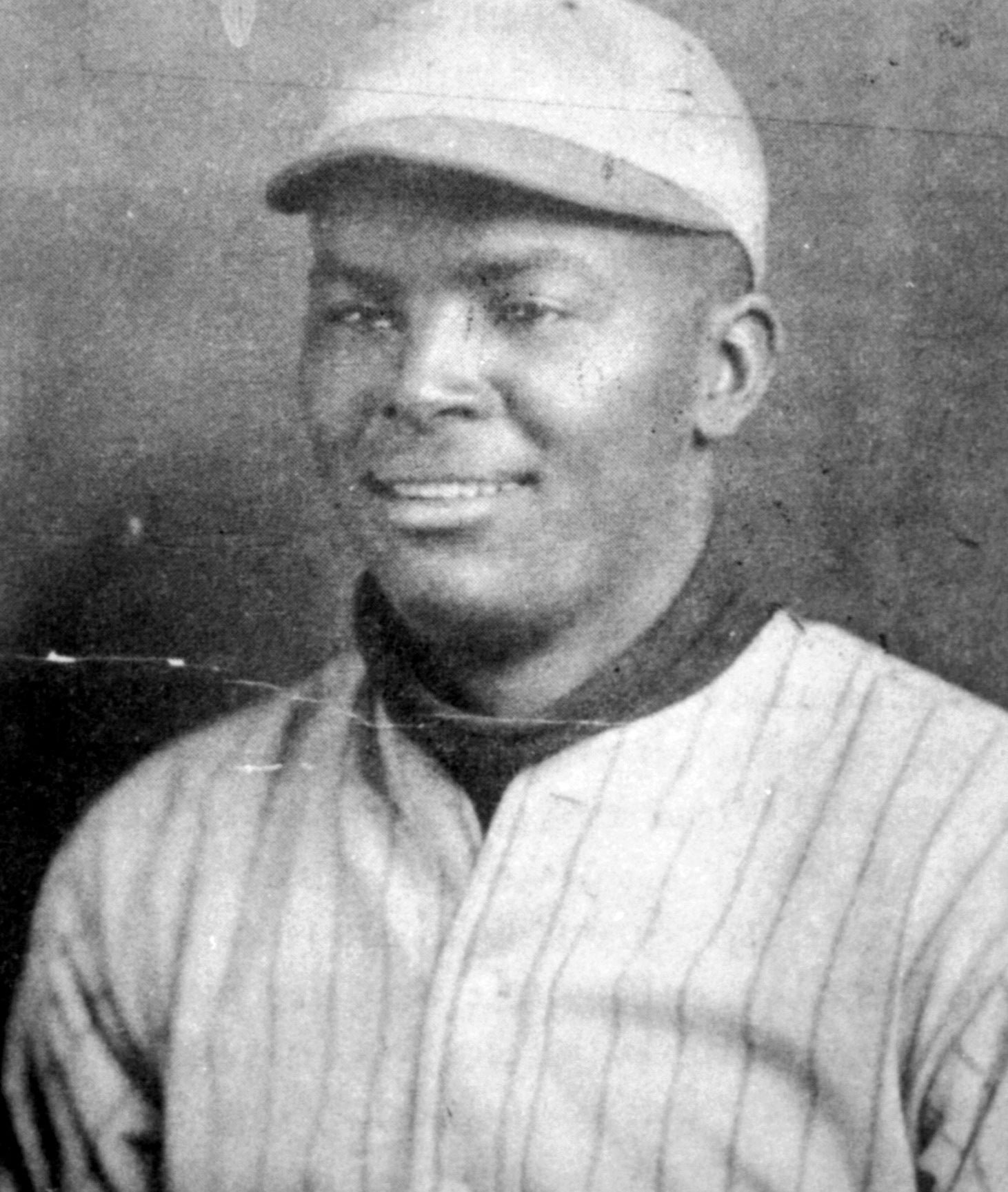

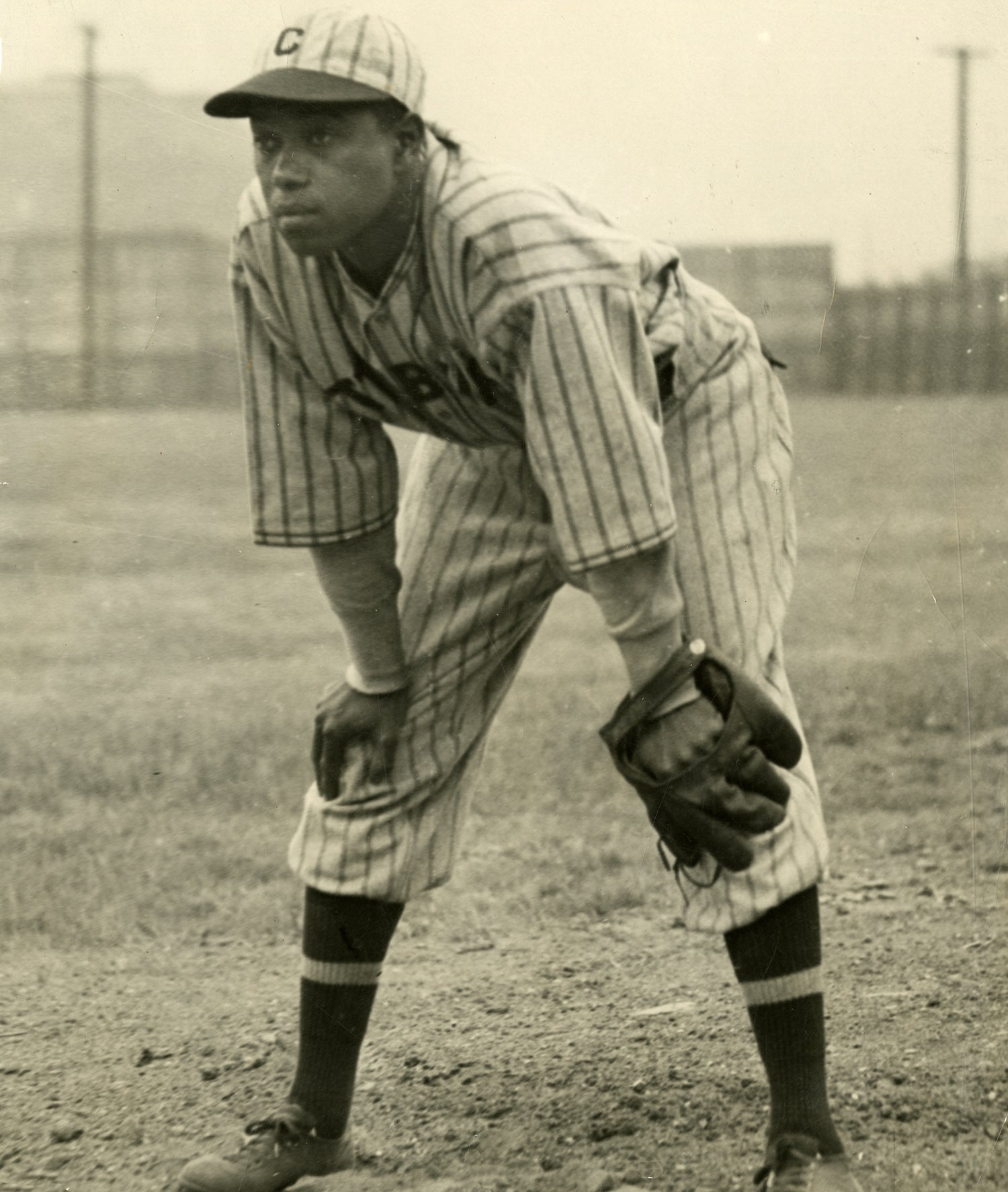

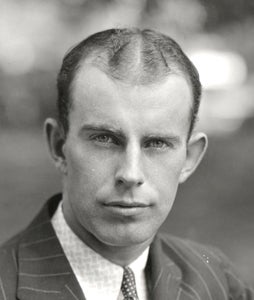

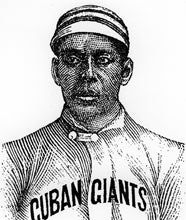

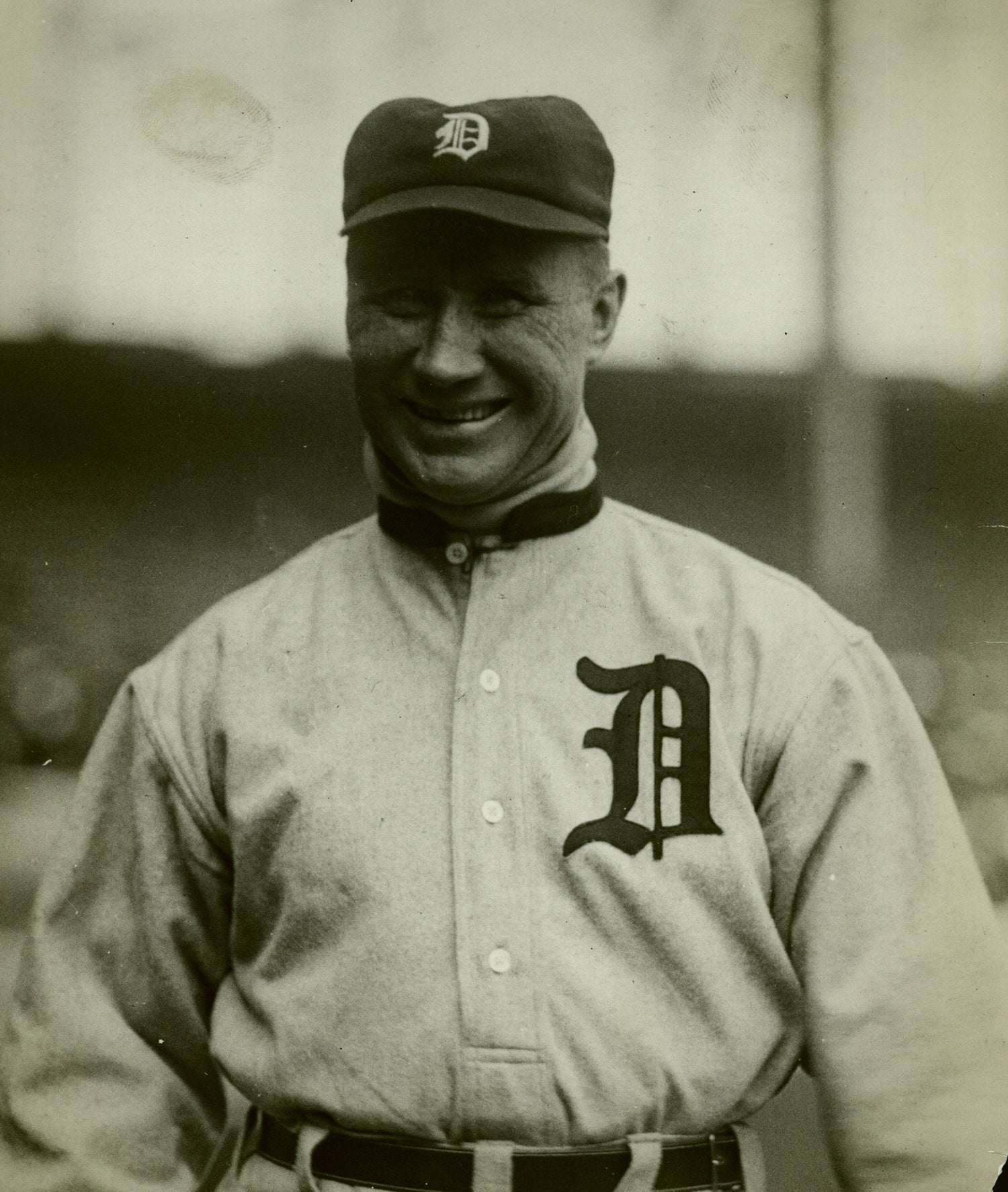

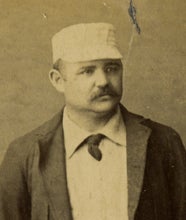

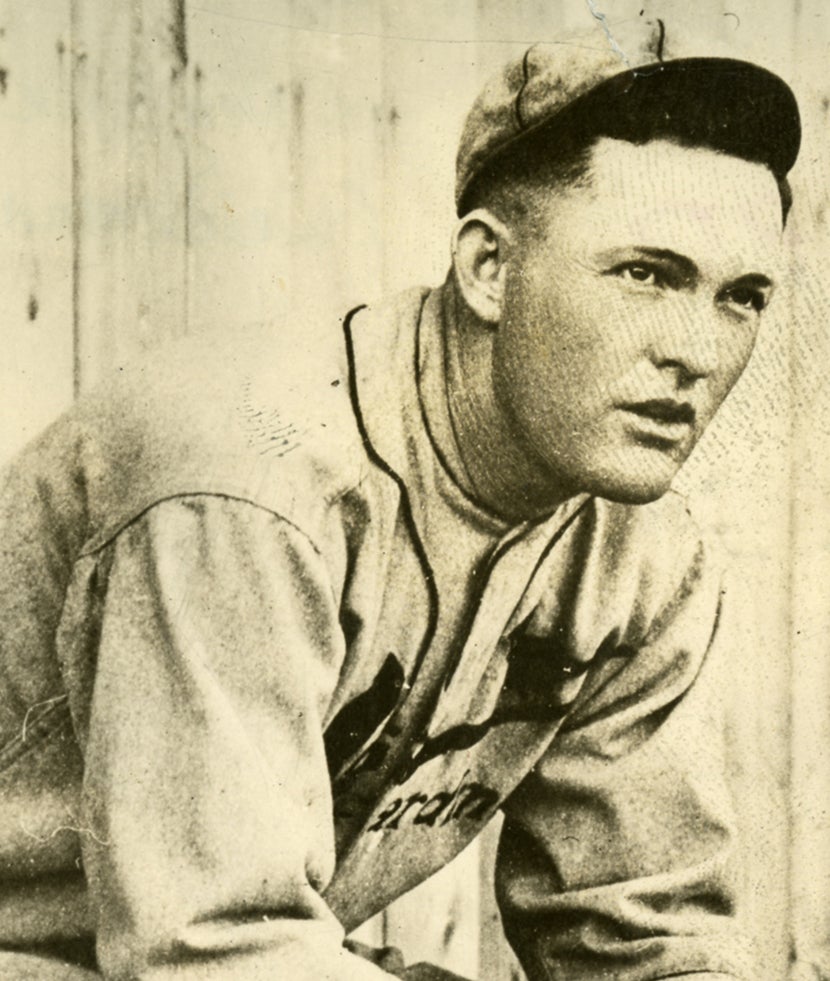

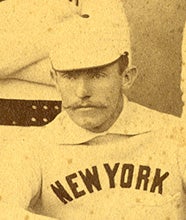

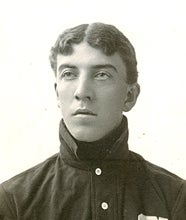

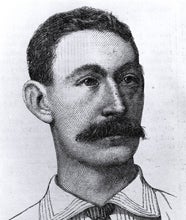

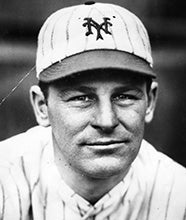

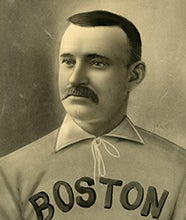

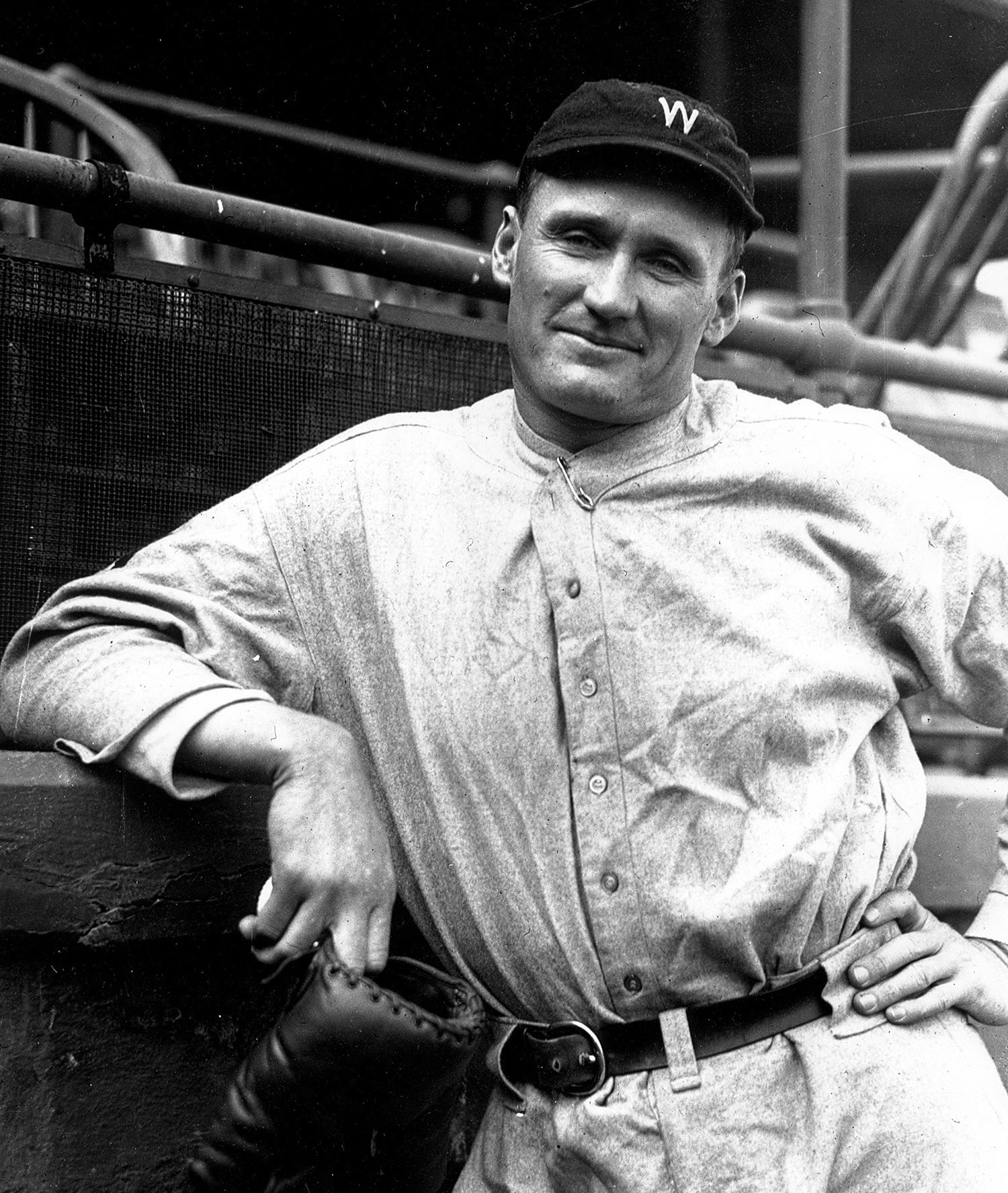

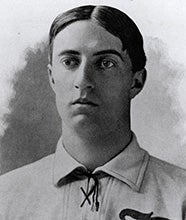

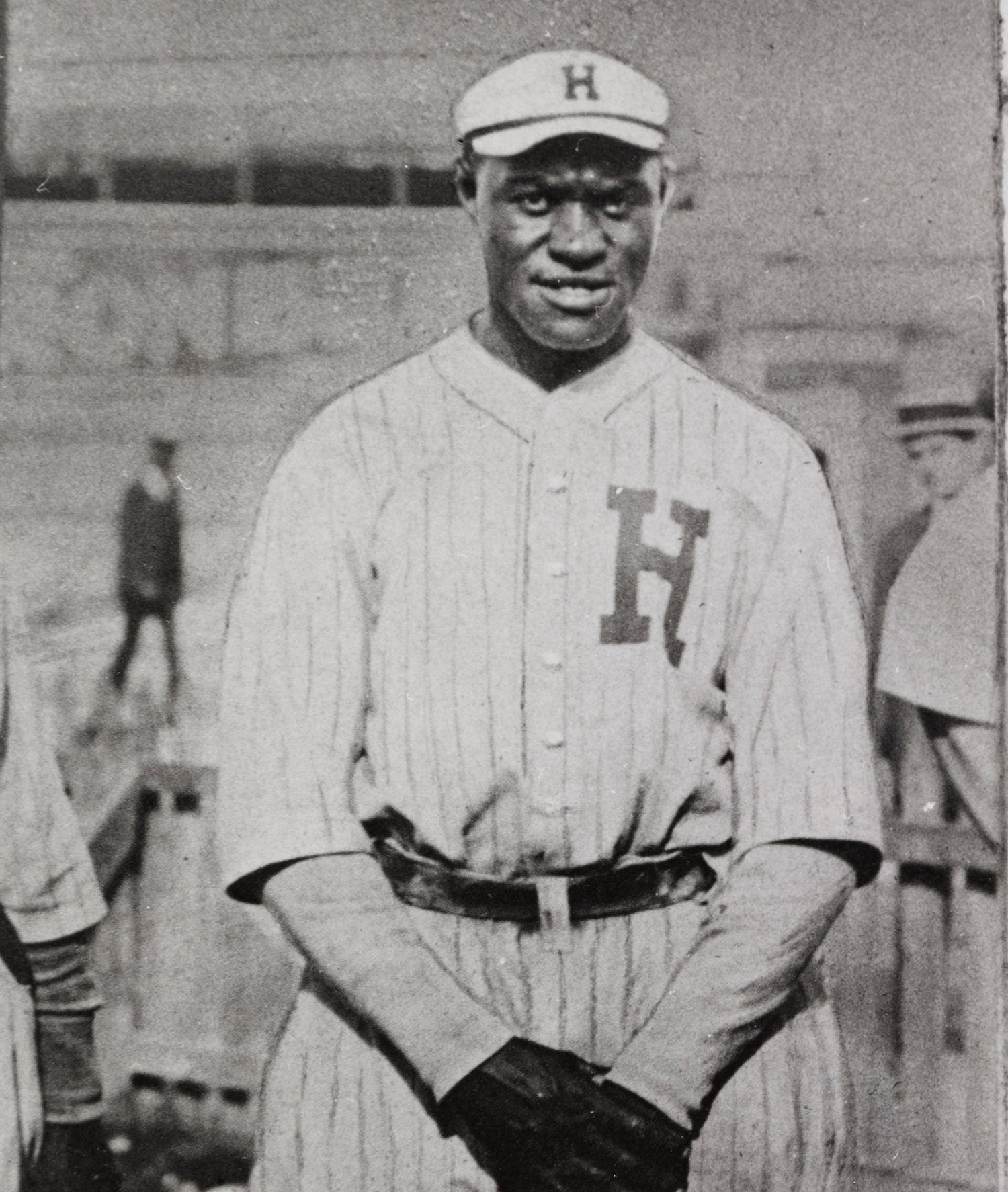

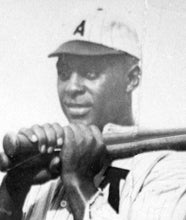

Breaking Cobb’s mark suddenly brought a 19th century player back into the news. His name was “Sliding Billy” Hamilton, a 5-foot-6 outfielder who had been elected to the Hall of Fame in 1961.

But when Brock surpassed Cobb, suddenly there were students of the game who rose to say, “Whoa, not so fast. There still remains Sliding Billy.”

It was true. Hamilton was in the record books with his 937 steals, even if set apart as a pre-1900 figure. And the pre-1900 barely explained his total. From 1886 to 1897, stolen bases were awarded for any number of base running advances: Moving up on a throw to another base, moving up on an error – all this and more contributed to the total.

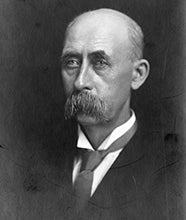

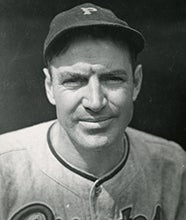

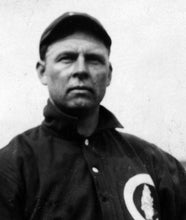

Still, no one ran up a total like Hamilton did. He was the best at what he did; the best of his era. In his first two years with the Phillies, 1890 and ’91, he had 102 and 111 steals, (in only 123 and 133 games, respectively), even as altered by modern research. His head-first slides were crowd pleasers, and he played center field for Philadelphia between two other Hall of Fame-bound outfielders in Big Sam Thompson (6-foot-2) and Ed Delahanty (6-foot-1).

Apart from his superlatives in stolen bases (his total has since been revised to 914), he had a .344 career batting average.

Remarkably, he scored 198 runs in 132 games in 1894, and there was nothing odd in the rules about runs scored then. No one has ever come close to that – Babe Ruth’s 177 in 1921 being the modern era mark.

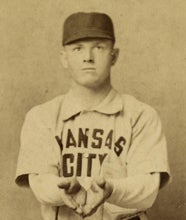

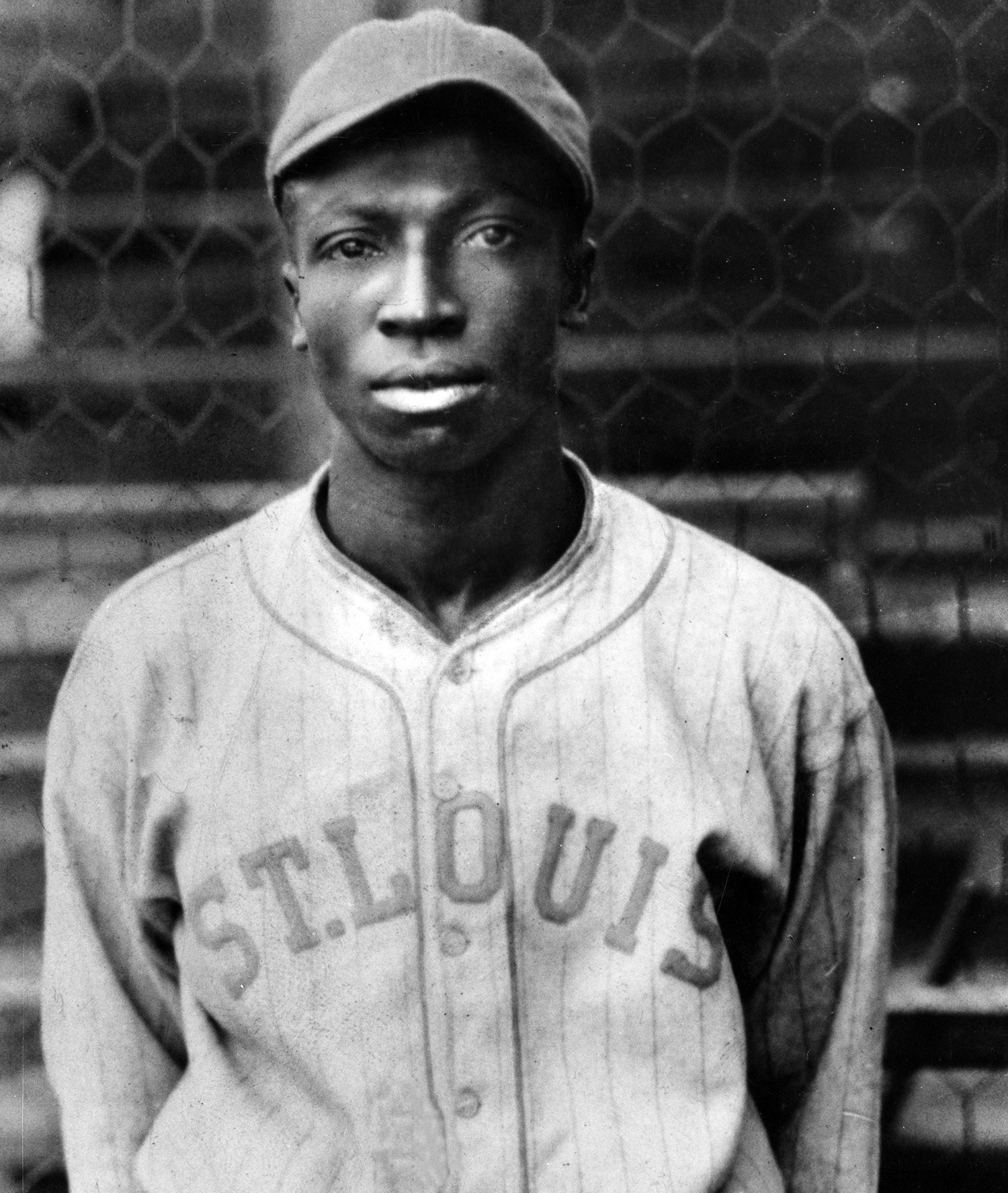

A native of Newark, N.J., Hamilton had been a high school sprinter who turned to pro baseball at age 22. He reached the majors with Kansas City Cowboys of the American Association (then a major league) in 1886 and went to Philadelphia when they folded two years later. He played 14 years in the major leagues, including six years with Boston, wrapping up his career in 1901.

Hamilton was a player/manager in the minors until 1910, stealing bases until he was 44. His last job in pro ball was as manager and part owner of Worcester in the Eastern League in 1916, the year after Cobb set his record of 96 thefts in one season.

Hamilton passed away on Dec. 15, 1940.

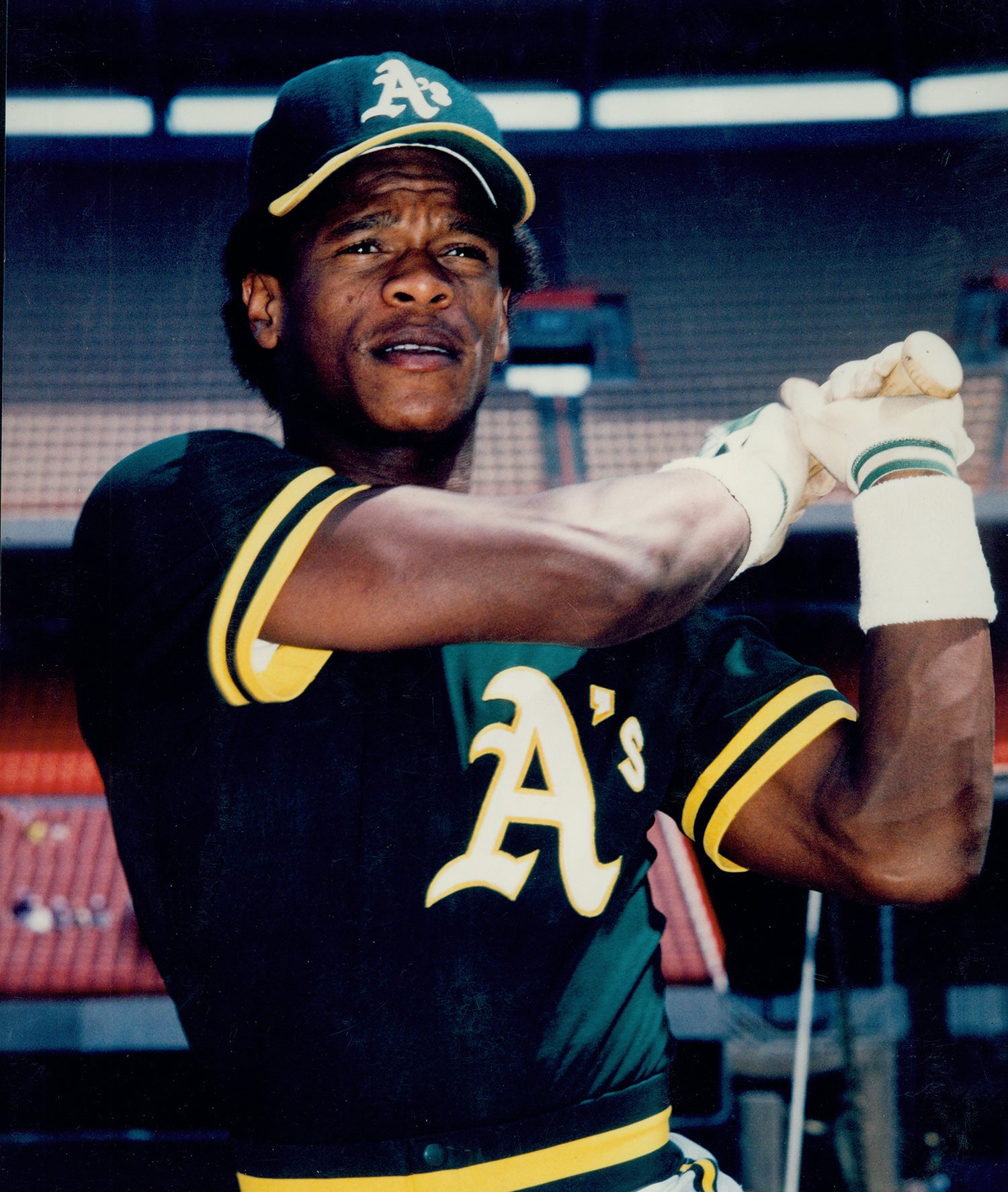

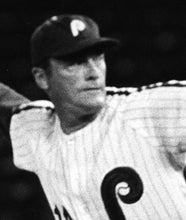

On Sept. 23, 1979, Brock stole the final base of his career. He made sure to get number 938 and surpass what was then considered Hamilton’s lifetime total.