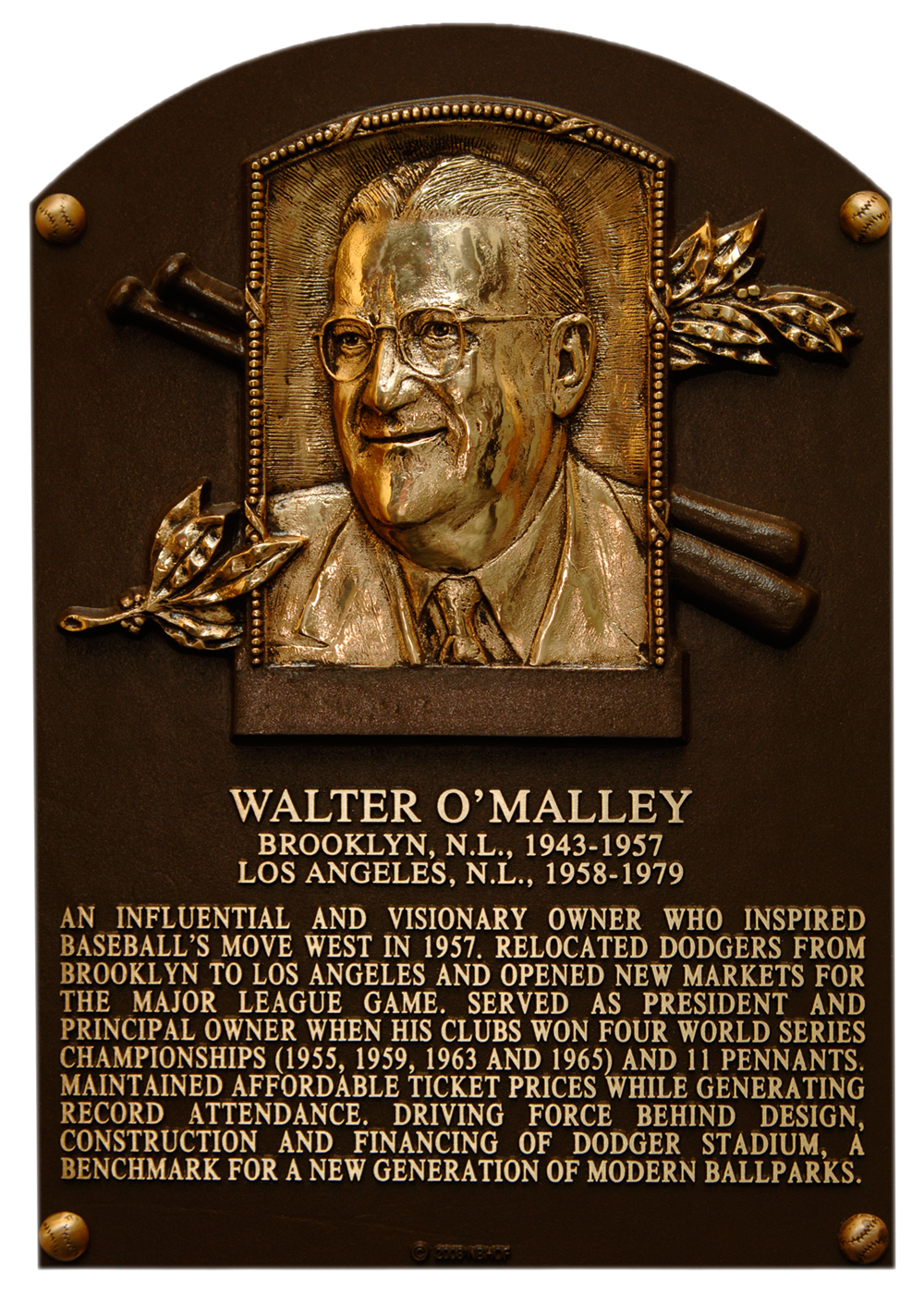

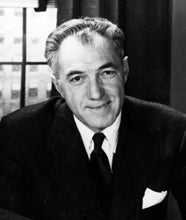

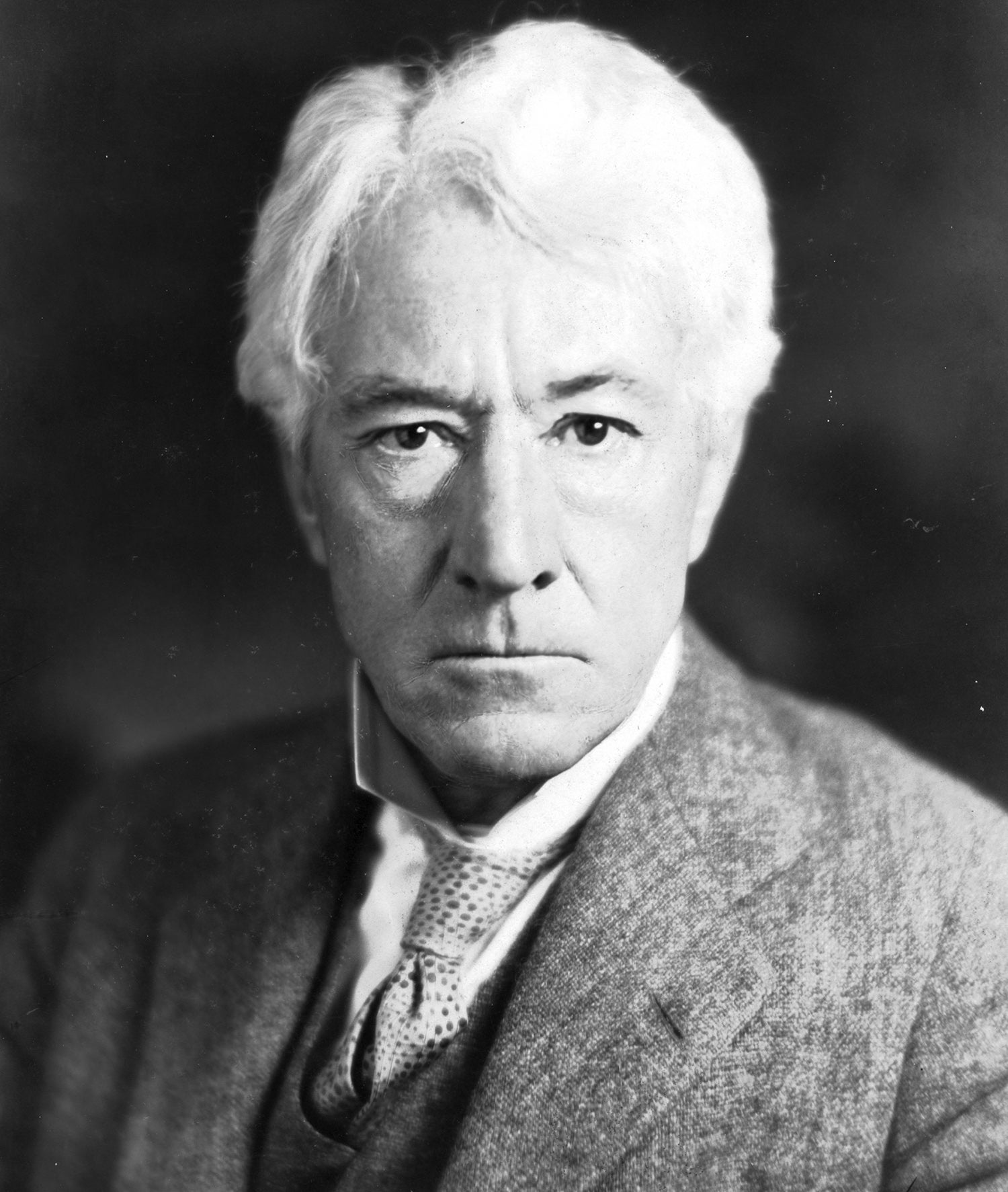

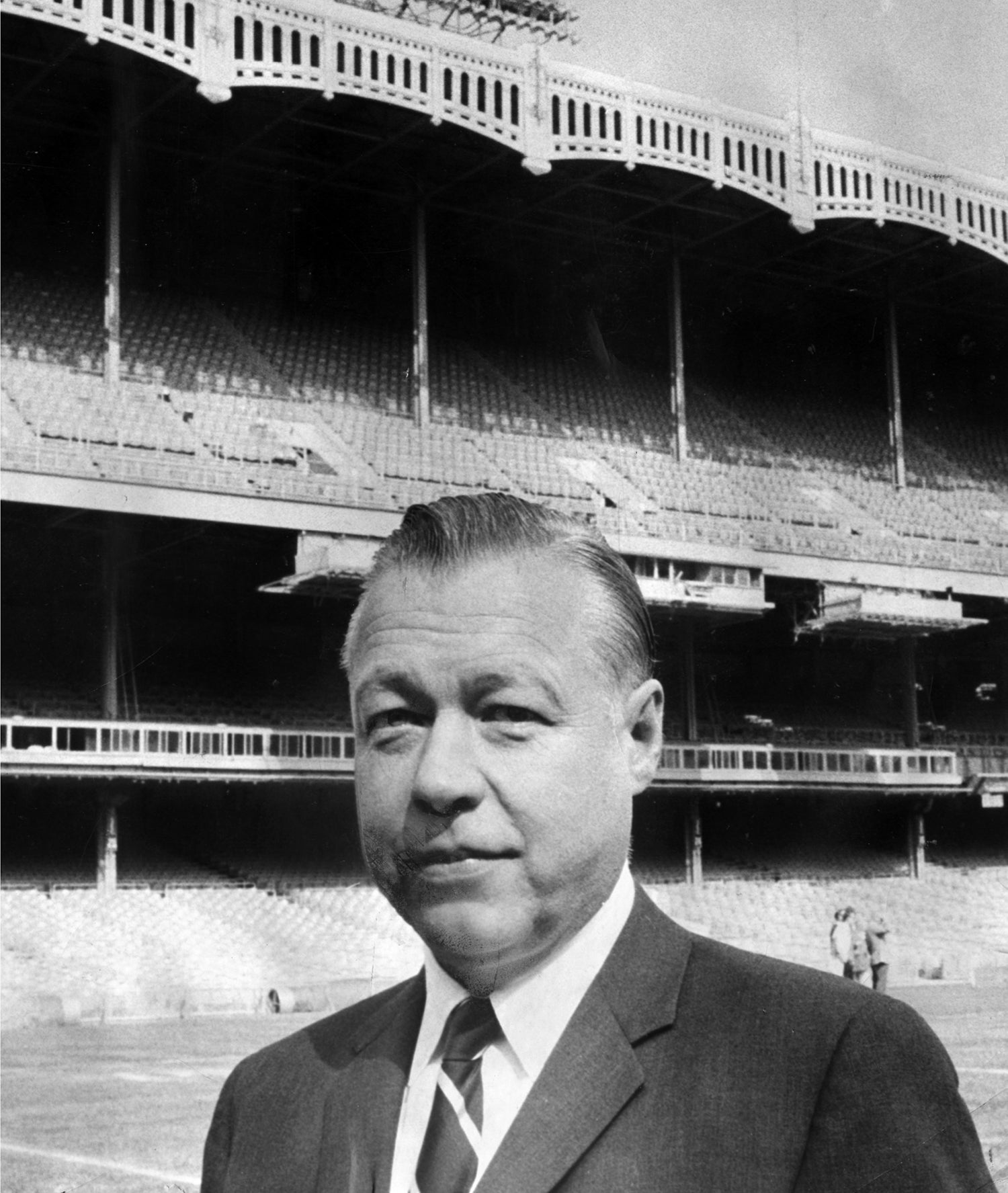

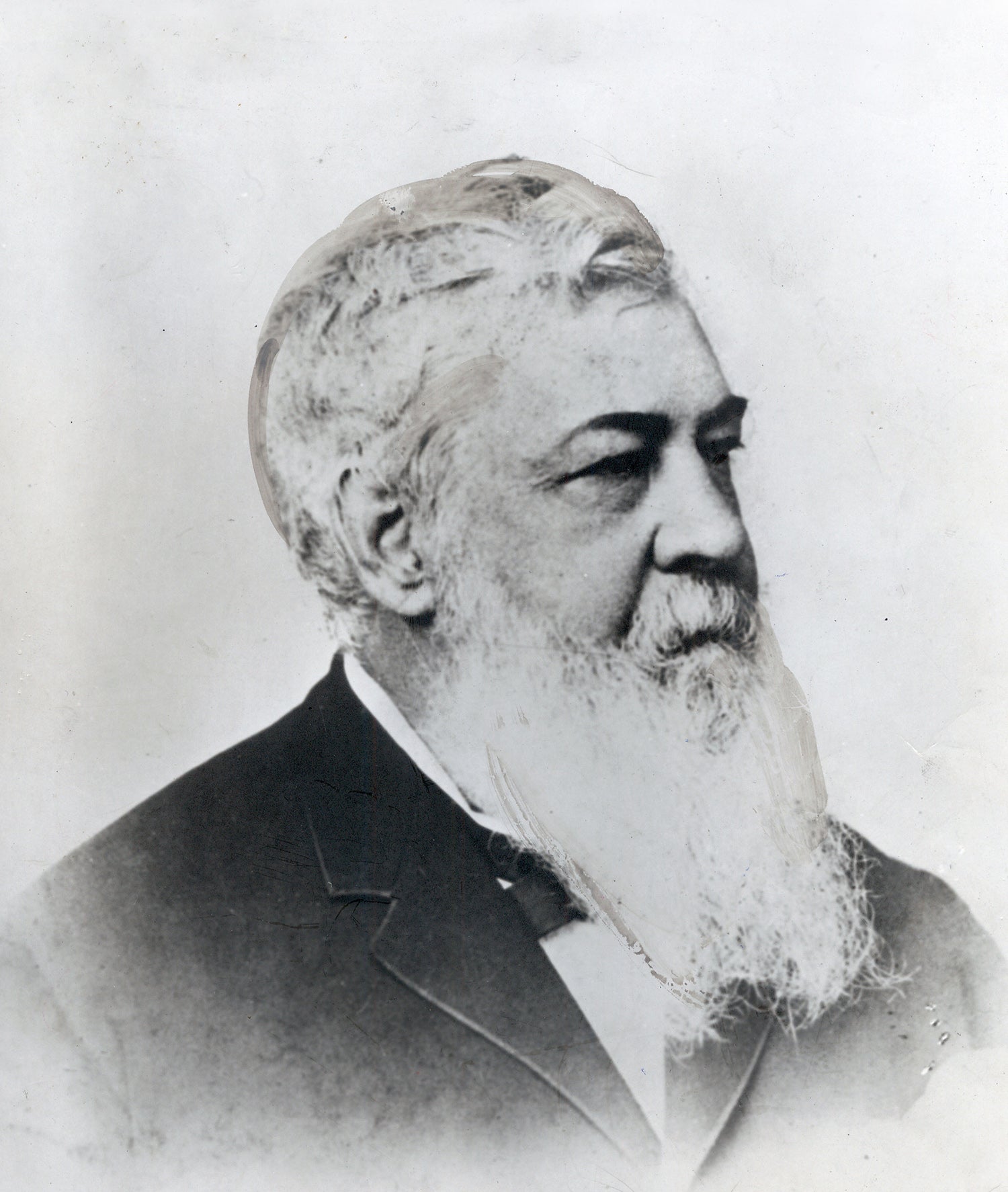

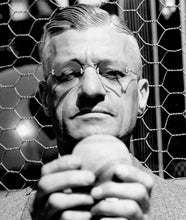

In his first week on the job as the president and principal owner of the storied Dodgers franchise, Walter O’Malley declared his philosophy in eight words: “We are going to concentrate on winning pennants.”

When asked to elaborate, he explained that he intended to build an organization to match the New York Yankees of the American League as a perennial powerhouse.

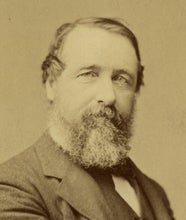

Until that moment, O’Malley had been known as the youngest and least visible member of an ownership group that had brought some stability and success to a long-troubled franchise. But as of autumn 1950, the job was not yet finished. The team had won just six pennants – and not a single World Series – in 50 years and talk of a dynasty seemed overreaching. It was at bit of blarney, some thought, from the warm and lively son of an Irish-American New Yorker.

But while he was quick with a joke and arm around the shoulder, O'Malley was, in fact, a happy and determined warrior. Anyone acquainted with the story of O’Malley’s life leading up to the day he assumed control of the Dodgers understood that if the new chief knew anything, it was how to win.

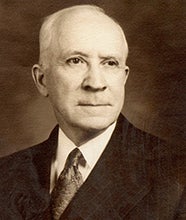

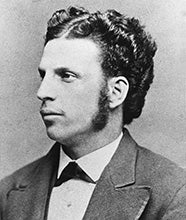

Born in the Bronx in 1903 and raised in Queens when it was still largely rural, O’Malley came of age at a time when boys were schooled in fierce, but fair, competition. Theodore Roosevelt’s “Man in the Arena” narrative was the role model for young men. O’Malley, with his love of the outdoors and spirited approach to life, fit the bill. He showed he was a leader early, rising in the ranks of a new organization called the Boy Scouts. As a teenager, he left home for Culver Military Academy in Indiana.

At Culver, where strength and discipline were the order of every day, O’Malley’s career as a bespectacled first baseman ended with a smashed nose. But he distinguished himself among his peers, winning election to a battalion office and becoming editor of the school newspaper. Later, at the University of Pennsylvania, he was the first student to be president of both the junior and senior classes. He was a dapper, constantly smiling young man with twinkling eyes and a quick mind. In a sign of things to come, he helped manage the school sports program and was honored as the most popular fellow in his class.

After earning a law degree at Fordham University in the midst of the Great Depression, O’Malley built the fortune that would lead to an owner’s box at Ebbets Field. O’Malley, though, would say that his future happiness was set with his marriage to Kay Hanson. Literally the girl next door at the O’Malley family summer home on Long Island, Kay was a bright and beautiful young woman who tried to talk Walter out of loving her because she had been treated for cancer and worried about being a burden to him. With all the certainty he later displayed in business, Walter refused to be dissuaded. Irving Berlin’s “Always” became their song and the marriage would last a lifetime. He playfully nicknamed her, “My Manager.”

A Dodgers fan long before her husband acquired a piece of the team in 1944, Kay O’Malley became a fixture at Ebbets Field, where she always kept score and knew everything about the players, including their children’s birthdays. She may have known the game better than her husband. But Walter O’Malley understood what made people and organizations tick.

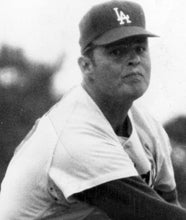

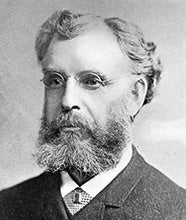

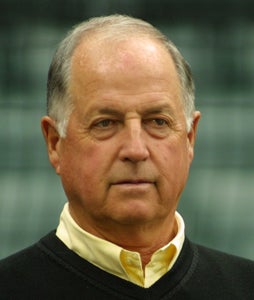

To make the Dodgers win, O’Malley named executives who would enjoy extraordinary authority and longevity. The two men most responsible for putting a team on the field, Lafayette Fresco Thompson and Emil “Buzzie” Bavasi, would each spend more than 20 years with the team, most of it working for O’Malley. “Walter let you do your job, and that was the key,” Bavasi said. That went for managers, too. O’Malley hired only two managers in the time he ran the franchise. His first, Charlie Dressen, led the team to pennants in 1952 and 1953. His second, Walter Alston, would serve for 23 years, winning seven pennants and four World Series titles.

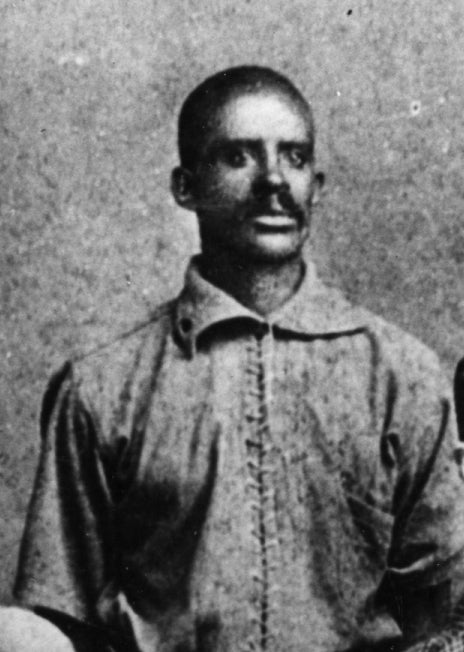

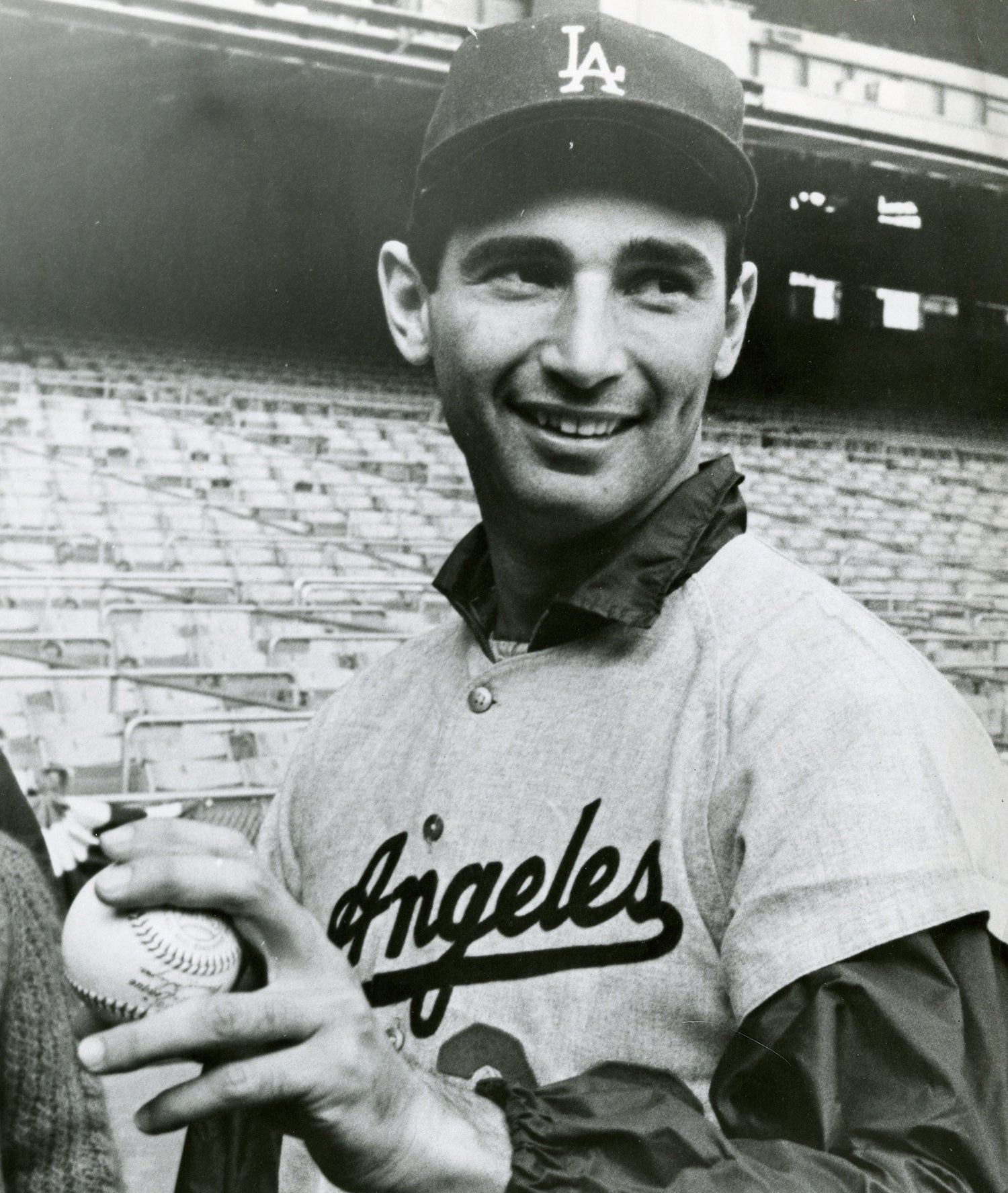

In O’Malley’s first season as Dodgers president, only Bobby Thomson’s famous playoff home run for the Giants kept the team from going to the World Series. But with the likes of Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Duke Snider and Carl Furillo on the field, the Dodgers grabbed the flag the next two years, establishing themselves as Yankees-style winners, except for one thing – they kept losing the Series to the Bronx Bombers. Finally, with Alston in the dugout, the Dodgers won the Fall Classic in 1955. O’Malley’s team had done what no Dodgers owner had ever done: They brought home a championship.

Unfortunately, O’Malley had trouble matching the team’s victory in the tougher game of stadium politics. From the moment he became involved with the Dodgers, O’Malley knew that Ebbets Field was running out of time. Expensive repairs kept the place open, but with fewer than 800 parking spots, it wasn’t suited to the coming age of suburbs and automobiles.

Faced with leaving Brooklyn one way or another, he chose to be a pioneer and, along with New York Giants owner Horace Stoneham, made the big league game truly national. The choice ended an era in Brooklyn and began one in Los Angeles, where O’Malley would make his vision of major baseball a reality.

The stadium was the key, and by 1957, O’Malley had already been working on it for a dozen years. He had consulted with legendary architect Buckminster Fuller, who imagined a geodesic dome for the Dodgers and experimented with engineer Emil Praeger on a small park nestled into the landscape at the famous Dodgertown Spring Training complex in Florida.

O’Malley envisioned a 56,000-seat, privately-owned ballpark in Los Angeles that would represent near perfection for players and fans. Dodger Stadium was designed to be a classic of California modern architecture with pastel colors and gracefully curved lines. The terraced and landscaped site would allow fans to leave their cars at nearly the same level as their seats. Once inside they would get their baseball framed with spectacular views of mountains and palm trees.

Of course it would take a few years to build Dodger Stadium. In the meantime, the team would play at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, a football facility. But Los Angeles was baseball crazy, and O’Malley was welcomed with a parade and enormous crowds – more than 78,000 for the first game.

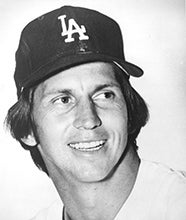

Dodger fans had to endure a rough first season as the 1958 team finished next to last. But the city that had waited nearly 60 years for Major League Baseball was rewarded the next season with a first-place finish, a playoff series victory over the Milwaukee Braves and a World Series championship. The Dodgers set a Series game attendance record – 92,706 in Game 5 – and in the regular season hosted two million fans for the first time.

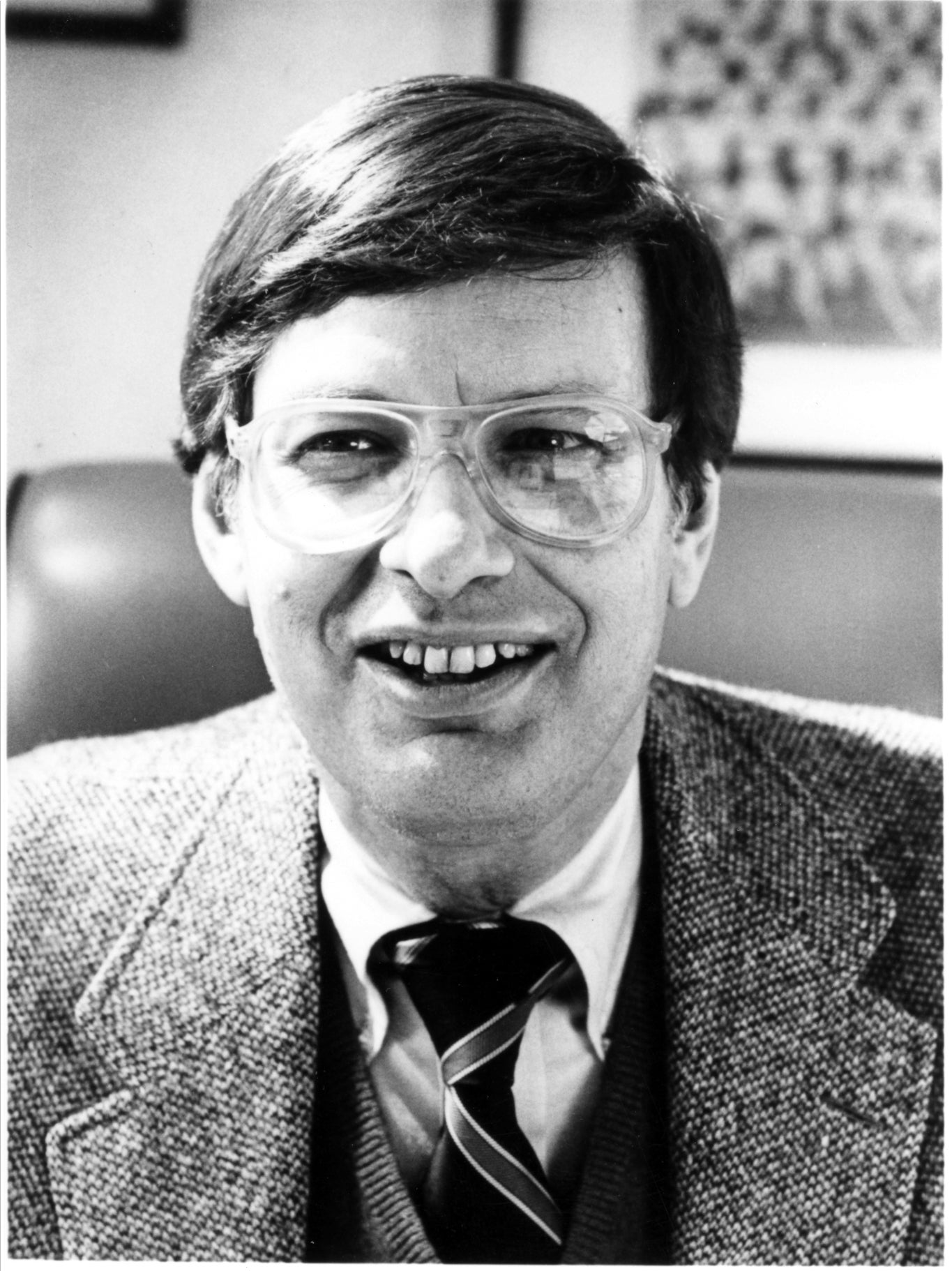

Dodger Stadium opened to rave reviews in 1962. At the house that O’Malley built, the Dodgers would win three more pennants and two more championships before he retired as president in 1969. During his tenure as president, O’Malley posted a record unequaled in the National League. No other team would win more games, pennants and World Series or draw more fans. Along the way, he and Stoneham proved that Major League Baseball could thrive on a national basis and opened the door for the game to expand to 13 more American cities over the next 50 years.

After transferring the Dodgers presidency to his son, Peter, O’Malley would serve as chairman of the board. He spent a record 28 years on the Executive Council of Major League Baseball and advised owners as they adapted to the arrival of a players union and free agency. He worked on baseball internationally, beginning with a team tour of Japan in 1956. Before his death in 1979, which came just a few weeks after Kay passed away, O’Malley would spread his gospel of fan-friendly management to university training programs and other sports. In 1978, he saw the team run by his son set a record for attendance of more than 3.3 million home fans.

Before he was elected to the Hall of Fame, O’Malley was recognized by the national media as one of the last century’s most powerful sports figures. But when asked about the great owner, broadcaster Vin Scully focused on the man, not the accomplishments. “He had a personality that was welcoming. It was his nature to reach out to people,” Scully said. “And I never, ever saw him discouraged.”

O'Malley passed away on Aug. 9, 1979. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 2008.