I think he’s the greatest professional athlete I ever met as far as attitude. I’ve got more respect for him than anybody in baseball. He’s a super individual.

- Home

- Our Stories

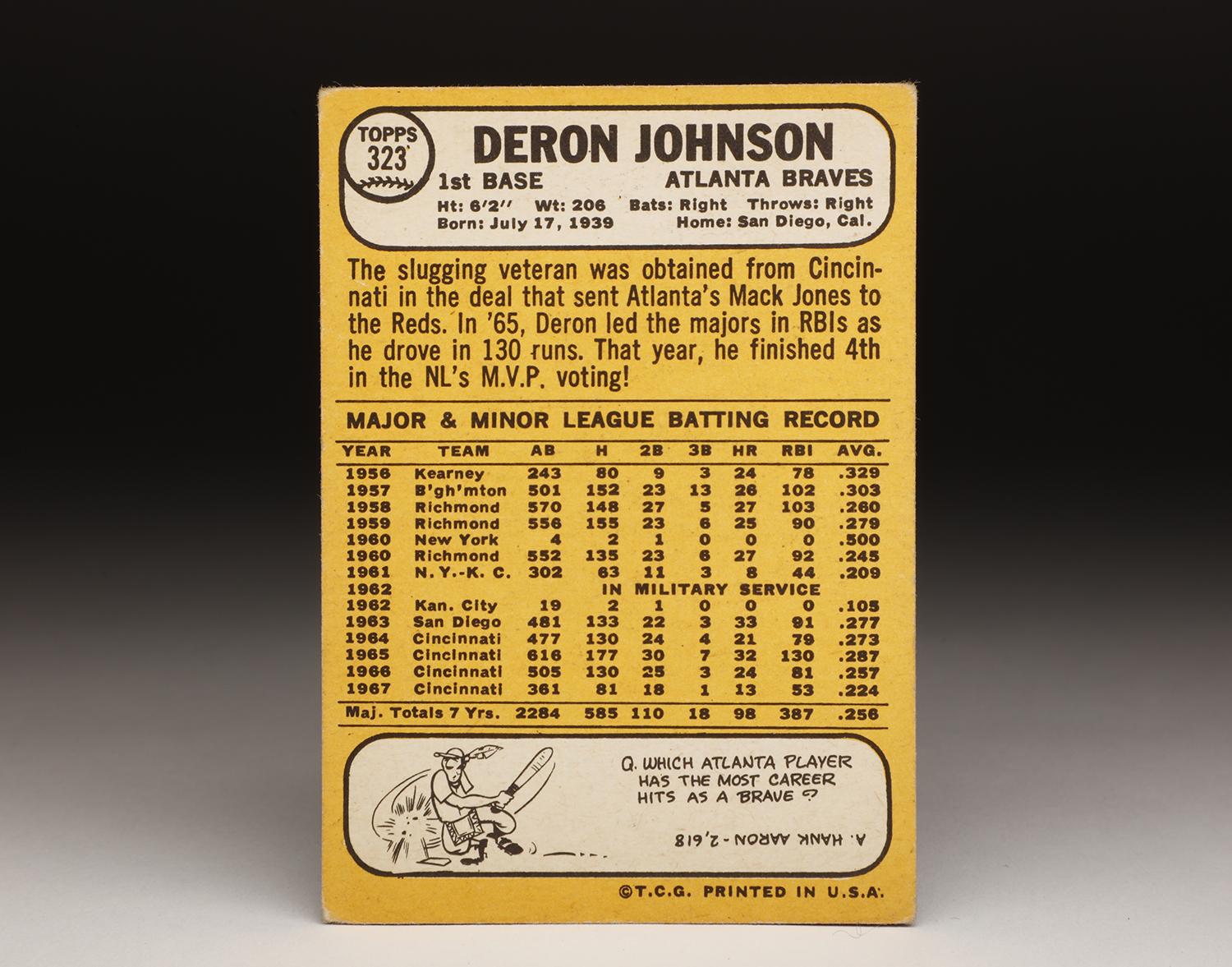

- #CardCorner: 1968 Topps Deron Johnson

#CardCorner: 1968 Topps Deron Johnson

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

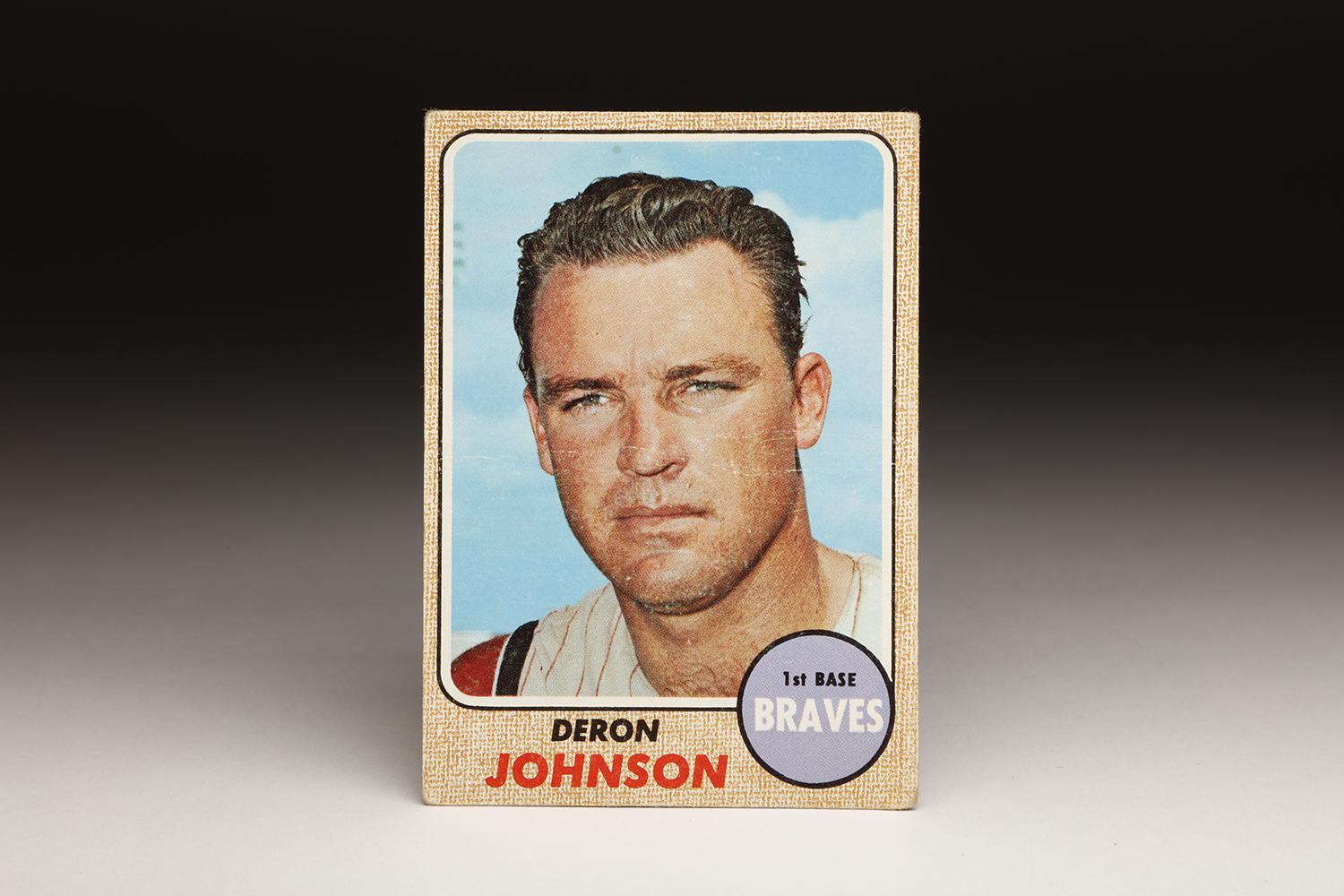

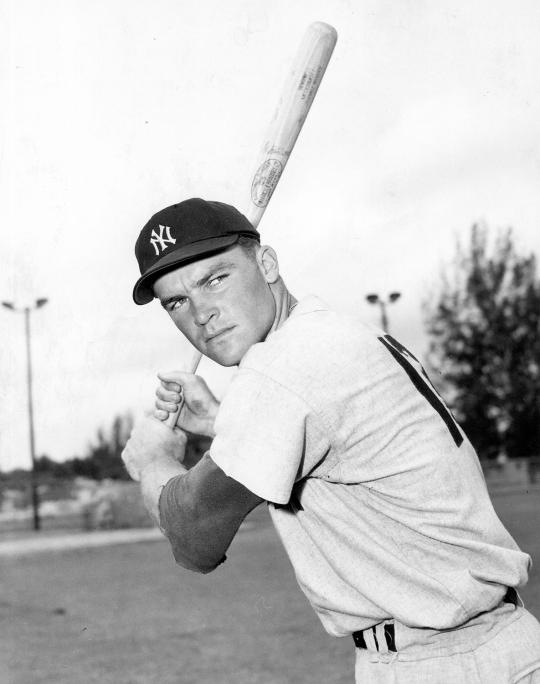

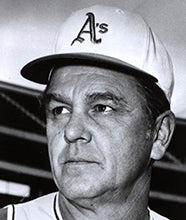

Whenever I see Deron Johnson’s 1968 Topps card, I’m reminded of John Wayne. I see a tough, grizzled character who seems like he should be rounding up cattle rustlers in the Old West. The old TV show, Gunsmoke, must have had a few characters who looked like this. Chiseled men, with solid, unsmiling jaws, men who did their jobs quietly and without fanfare.

In many ways, that’s the kind of man that I remember when I recall the late Deron Johnson, a good man who died too young.

How tough was Deron Johnson? Like Alex Karras did so famously in the raucous Mel Brooks comedy, Blazing Saddles, Johnson once punched a horse! Then again, you might say that the horse had it coming. Thankfully, both Johnson and the horse emerged from the incident relatively unscathed.

Johnson’s toughness belied his true personality. Wherever he played, he became one of the most popular players on the team. His work ethic, his refusal to complain, and his generous, loyal nature all made sure of that. A search through his biographical file in the Hall of Fame’s Library turns up nary a bad word from anybody in baseball about the rugged slugger.

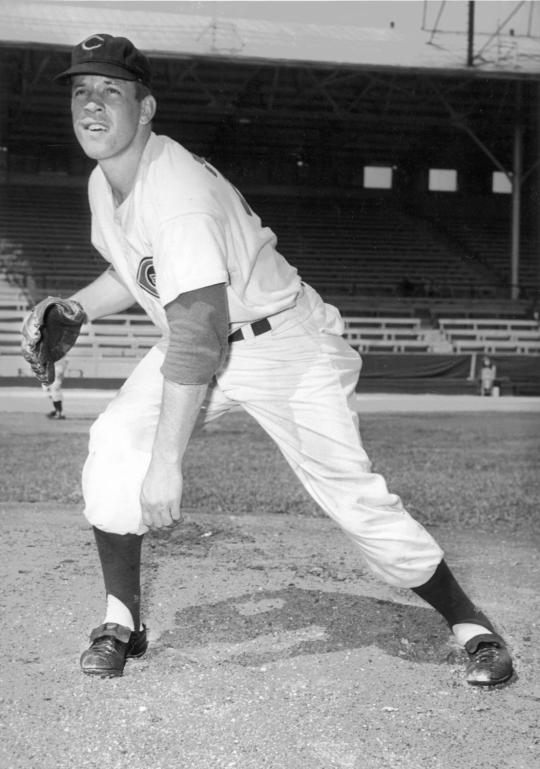

Aside from Johnson’s hardened appearance, there is something else of note about his 1968 Topps card. Though he is clearly wearing the colors of the Cincinnati Reds, Johnson is seen capless on the card. Topps had the foresight to take a picture of him in Spring Training of 1967 without a cap, just in case he might be traded. Sure enough, that’s exactly what happened. After the ’67 season, the Reds traded him to the Atlanta Braves for a package of outfielders Jim Beauchamp and Mack Jones and pitcher Jay Ritchie. That’s why the Topps card designates him as a member of the Braves.

It’s probably a good thing that Johnson never appeared on a Topps card wearing the uniform of the Braves. He would undergo a difficult season with Atlanta in 1968. Bothered by a series of injuries, including a hamstring pull and a groin injury, he hit only .208 with eight home runs. It was his first down year after becoming a regular with the Reds back in 1964. Johnson struggled so badly that he lasted only one season in Atlanta; the following winter, the Braves traded him to the Philadelphia Phillies, where he would enjoy a career renaissance.

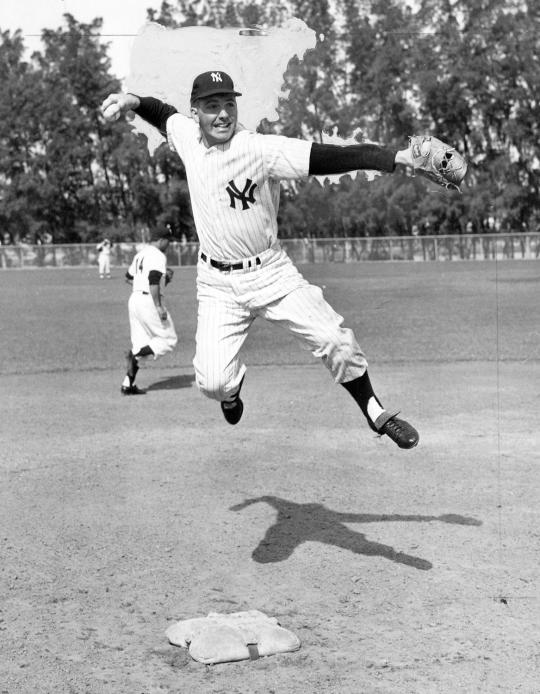

Johnson’s long, professional road to Philadelphia actually started years earlier in New York. A top prospect who originally signed with the New York Yankees, Johnson received the label of “another Mickey Mantle” from some of the sportswriters covering baseball in the city. In 1960, the Yankees brought him to the major leagues, hoping that he could fill a role as their starting third baseman. Johnson faced two major problems. As a third baseman, Johnson made a good first baseman; at 210 pounds, he lacked the agility and range needed for the hot corner. He also faced a roadblock in Clete Boyer, the veteran mainstay who had made fielding at third base an art form.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

With Johnson blocked by Boyer, the Yankees faced a logjam. In June of 1961, they decided to stay with Boyer and move Johnson, trading the young slugger to the Kansas City Athletics. Johnson and right-hander Art Ditmar went to Kansas City for left-hander Bud Daley in what turned out to be one of the few unproductive trades that George Weiss made with A’s owner Arnold Johnson. A better plan would have been for the Yankees to keep Johnson and make him a first baseman. He would have been an ideal successor to Moose Skowron, who had just turned 30 and would become an ex-Yankee within two seasons.

While the Yankees would come to regret the Johnson trade, the A’s did not directly benefit from the transaction. They used Johnson in a utility role, playing the infield and outfield corners, but he never gained any traction in Kansas City. He needed regular at-bats to maintain his swing and timing, but didn’t receive that kind of playing time from the A’s. After batting .216 in 1961, he spent the 1962 season as a pinch-hitter, but collected only two hits in 19 at-bats. The A’s gave up on him, sending Johnson to the Reds in April of 1963 and receiving only cash in return.

The Reds wisely sent Johnson back to Triple-A, where he could re-find his swing and his timing. He did just that, blasting 33 home runs and slugging .541 in the Pacific Coast League for the San Diego Padres. Feeling that the year in the minor leagues was just the antidote, the Reds made him their starting first baseman in 1964. Johnson responded with a .273 batting average and 21 home runs, making him the third most productive power hitter on a team featuring Frank Robinson and Vada Pinson.

Johnson’s first year with the Reds set the stage for a banner follow-up in 1965. Prior to the season, the Reds made some news by shifting Johnson from first base to third base. The move would have little effect on Johnson’s hitting. In fact, he reached career highs in almost every category: 32 home runs, a .287 batting average, a .515 slugging percentage, and 130 RBI. The latter statistic led the National League. Johnson played so well that summer that he finished fourth in the MVP balloting, behind such illustrious names as Maury Wills, Sandy Koufax, and the No. 1 finisher, Willie Mays.

Compared to his early years with the Yankees and A’s, Johnson had transformed his approach as a hitter. Reds pitcher Joe Nuxhall, who had played with Johnson in Kansas City, noticed the change.

“With the Athletics, Deron was swinging from his heels on every pitch,” Nuxhall told Earl Lawson of the Cincinnati Post. “[He] tried to pull everything. You never saw him hit shots to right [field].” As a member of the Reds, Johnson regularly pushed pitches to the opposite field, sometimes of home run distance.

Johnson was now being heralded as a star, but as with many players, he was unable to repeat his peak performance beyond the one season. Still, he remained a productive player for the Reds, even enduring another position switch in 1966. Shifted from third base to left field, Johnson did so without complaint and continued to put up solid numbers. His production would have been better, if not for a sore shoulder that plagued him beginning in Spring Training.

In 1967, injuries limited Johnson to 108 games. Concerned about his health, and also believing they had a worthy successor at first base in a young Lee May, the Reds decided that a trade made sense that winter. Hence the deal that sent Johnson to the Braves.

After his off year in Atlanta, Johnson’s trade value had fallen off so much that the Braves sent him to the Phillies for only cash in return. Now 30 years old, Johnson set about repairing his career. He won the first base job in Philly and hit 17 home runs while drawing 60 walks.

Johnson played even better the next two seasons. In 1970, he hit 27 home runs and earned some back-of-the-ballot support in the MVP voting. Then came the explosion of 1971. Johnson ripped 34 home runs, a career high, while slugging .490 and drawing 72 walks. For Johnson, it was his best season since his career year of 1965.

Like many of the Phillies, Johnson struggled badly in 1972. Injuries limited him to 96 games. He hit only .213. As a team, the Phillies fared worse, winning only 59 games to finish dead last in the National League East.

By 1973, Johnson was 34 years old and ready to concede first base to the younger and more athletic Willie Montanez. After appearing in only 12 games, the Phillies dealt the veteran first baseman to the Oakland A’s, the defending world champions, receiving minor league infielder Jack Bastable in return. Phillis GM Paul Owens later admitted that he could have asked for more in a trade for Johnson, but he didn’t want to ruin the chance of Johnson joining a contending ballclub. That’s how much Owens liked and respected Deron Johnson.

Johnson’s teammates in Philadelphia thought similarly of him. “I think he’s the greatest professional athlete I ever met as far as attitude,” Phillies shortstop Larry Bowa told Frank Dolson of the Philadelphia Inquirer. “I’ve got more respect for him than anybody in baseball. He’s a super individual.”

In the meantime, the A’s featured a talented and deep team at most positions, and had few weaknesses. One of them was the lack of a productive DH.

“Deron Johnson is the DH we’ve been looking for,” manager Dick Williams told reporters in assessing the trade made by owner Charlie Finley. “We changed our thinking on the DH. At first we thought we needed someone with speed who made contact.” In Johnson, the A’s had decided to go with long ball potential and run production.

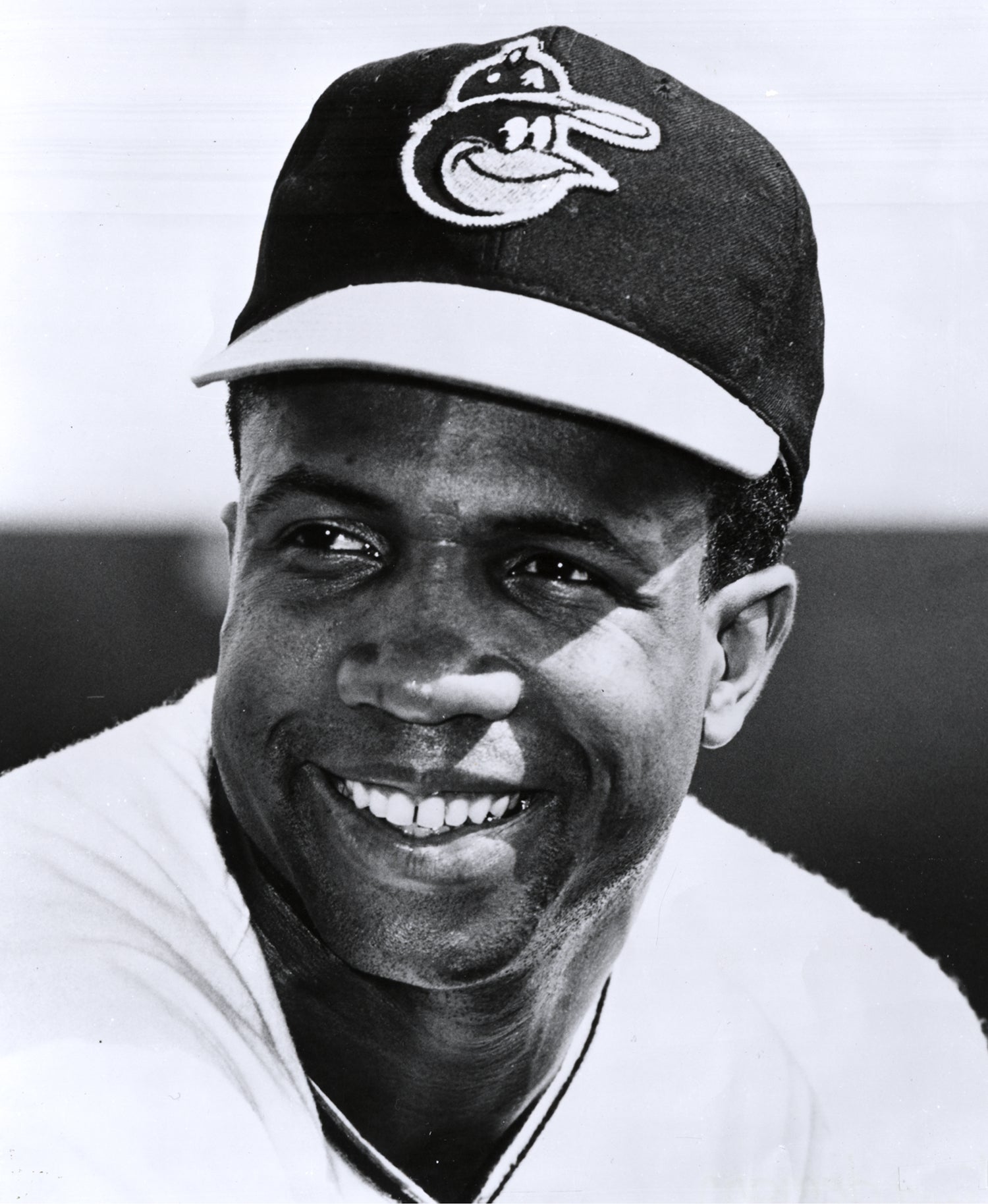

Johnson provided exactly that, deepening the Oakland lineup by hitting 19 home runs in 131 games. With Johnson playing a key supplemental role, the A’s won their second consecutive American League West title.

Johnson remained with the A’s throughout the postseason, including the World Series. With his playing time limited because of the lack of a DH in the Series, he still managed to rack up three hits in 10 at-bats. He also earned the first World Series ring of his career when the A’s upended the New York Mets in seven games.

A slow start to the 1974 season, along with the inevitable decline that comes with advancing age, led to a change. On June 24, the A’s sold Johnson, hitting just .195 with seven home runs, via waivers to the Milwaukee Brewers. Although less than a year removed from one of his most productive seasons, Johnson had been unable to find his stroke after injuring his thumb in August of 1973. In February, Johnson had expressed his wish to remain with the A’s for the rest of his career. “For six years, before I came to Oakland, I was with losing clubs,” Johnson told Sport Magazine. “I want to stay here [in Oakland] until I quit baseball.”

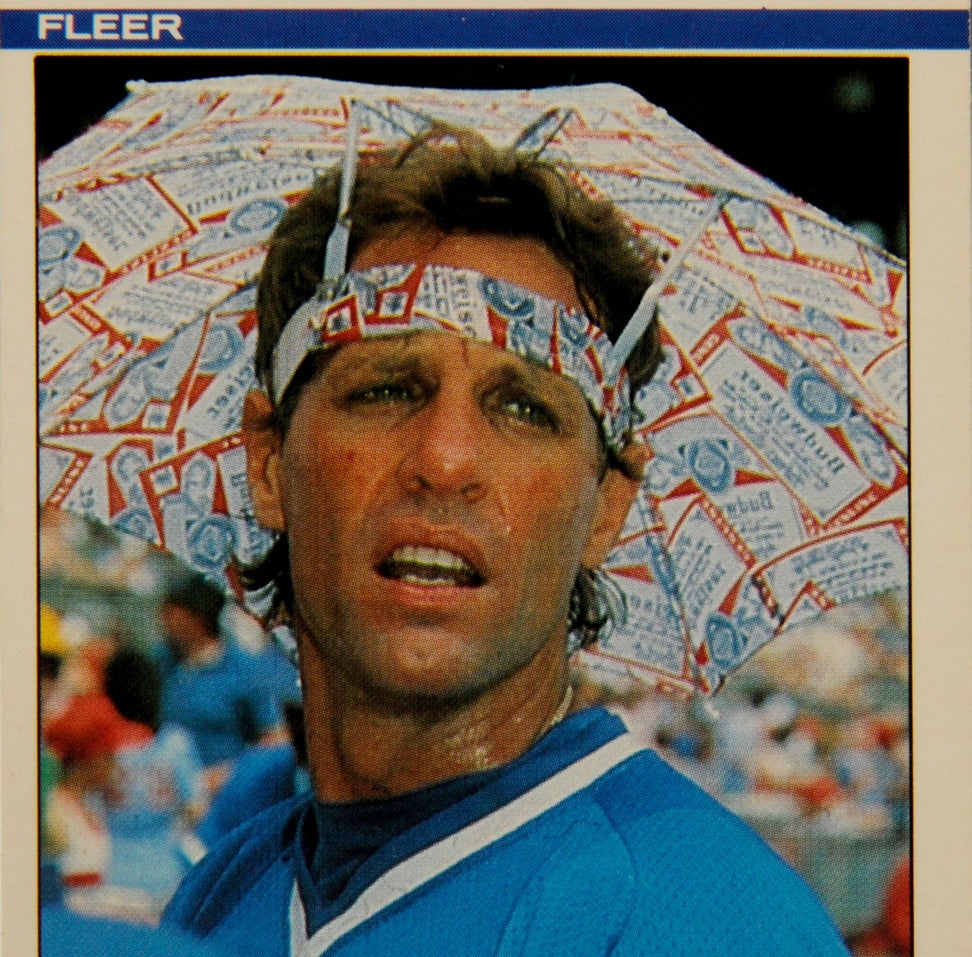

In 1968, the Philadelphia Phillies purchased Deron Johnson from the Atlanta Braves. It was in Philadelphia that Johnson saw a resurgence in his career, as he was able to play first base and saw his batting average steadily rise over the next three seasons. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

In selling Johnson’s contract to the Brewers, the A’s had ended that dream. The sale of Johnson also angered many of his A’s teammates, who liked Johnson. In a short time, Johnson had become one of the most popular players in the clubhouse.

Over the next two and a half seasons, Johnson bounced from Milwaukee to Boston to Chicago and back to Boston. In June of 1976, the Red Sox released him, ending his long career at the age of 37.

Johnson made such a good impression on the Red Sox that they wanted to hire him as their first base coach. When that deal fell through, he turned to minor league managing. From there, he returned to the major leagues as a coach, taking a job with the Angels. That’s when Johnson cemented his reputation as one of the strongest men in the game.

“One day he came to the park with a black eye and bruises all over his body,” recalled Angels GM Buzzie Bavasi in an interview with the Los Angeles Times. “Said he had been kicked by one of the horses he used to raise. He looked awful and I told him I was sorry and he said, ‘Yeah, but you should see the horse.’ ”

Johnson’s son, Dominick, confirmed the story in an interview with the Los Angeles Times. “The horse was named ‘Nugget,’ and he kicked dad when he walked behind him. Dad punched him right back.”

Hallmarked by that anecdote, Johnson’s tenure with the Angels marked the start of a long stint as a coach, including time with the New York Mets, the Phillies, Seattle Mariners, the White Sox, and again with the Angels.

While working with the Angels as their hitting coach in 1991, Johnson was given a diagnosis that no one wants to hear: He had cancer in both of his lungs. After receiving word of the diagnosis, Johnson asked the Angels’ beat writers not to mention his illness in print.

Johnson’s doctor told him that he could opt to be hospitalized, where he could receive chemotherapy treatment. Johnson said no. Knowing that his illness was terminal, Johnson opted to remain with the Angels and continue his coaching duties. At one point, he had to carry an oxygen tank with him to the ballpark. Still, he carried on with his work.

After the season, Johnson returned to his home in California so that he could be with his family. He again chose not to check himself into the hospital; his family life came first. For those who knew him, the decision typified a true family man like Johnson.

Johnson hoped to be strong enough to report to Spring Training in 1992, but the spread of the disease left him in a weakened condition. He simply did not have the strength to report to spring camp in Arizona. On April 25, Johnson died at the age of 53.

There’s no doubt that Johnson was a brave, tough man. A look at his 1968 Topps card hinted at that, while the steely way that he faced cancer confirmed that character trait. But there’s also little doubt that Johnson’s toughness sometimes obscured his other qualities: Hard work, a sense of humor, and loyalty to his teammates.

I’m still searching Johnson’s file to find a negative word that someone might have said about him. I have a feeling I’m never going to find that word about Deron Johnson.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

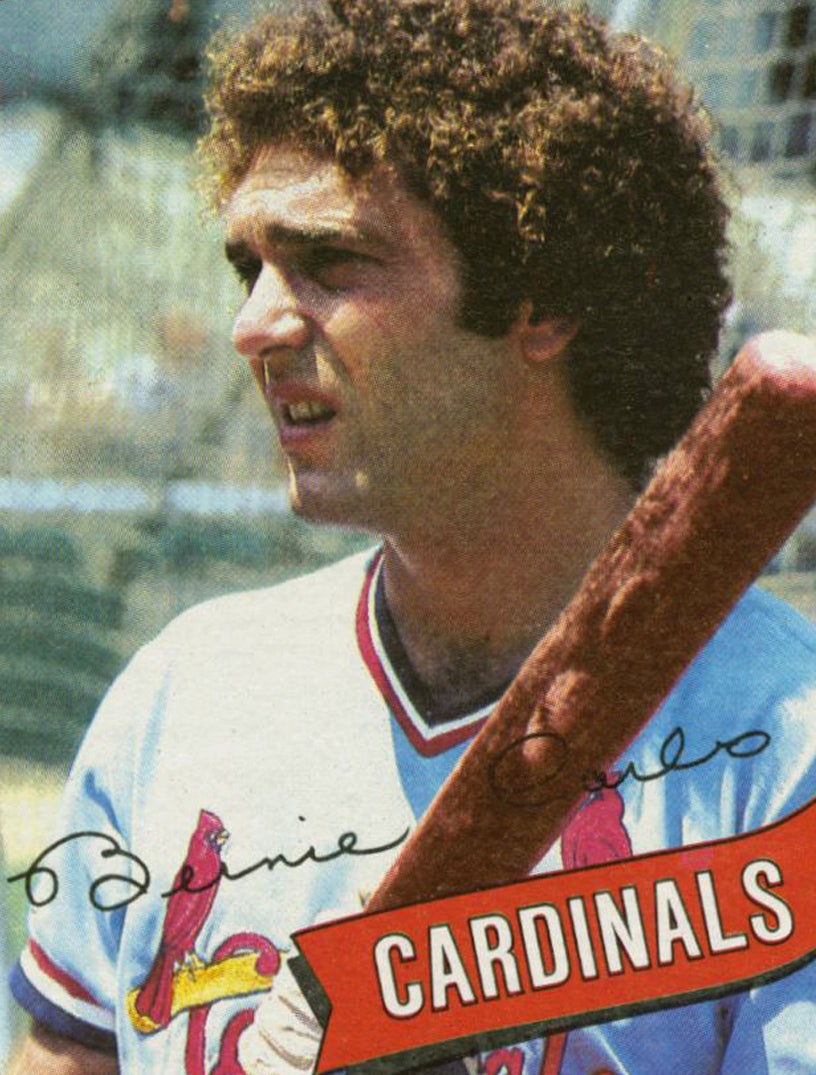

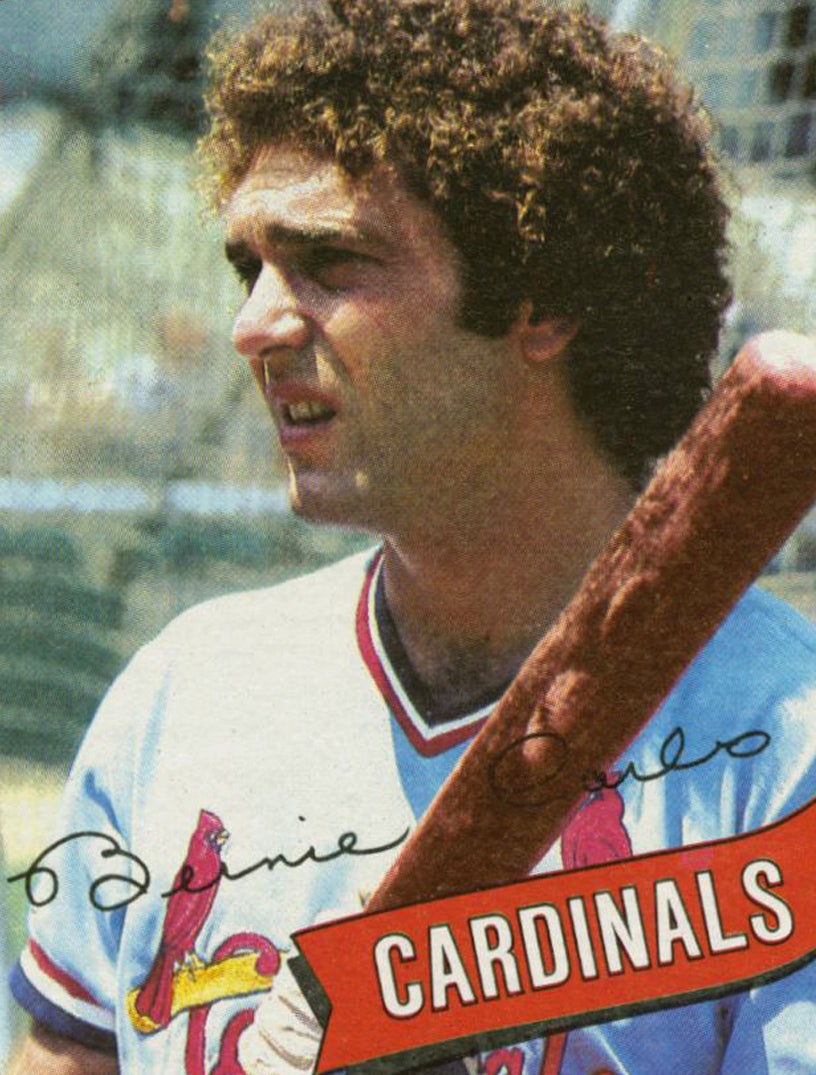

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bernie Carbo

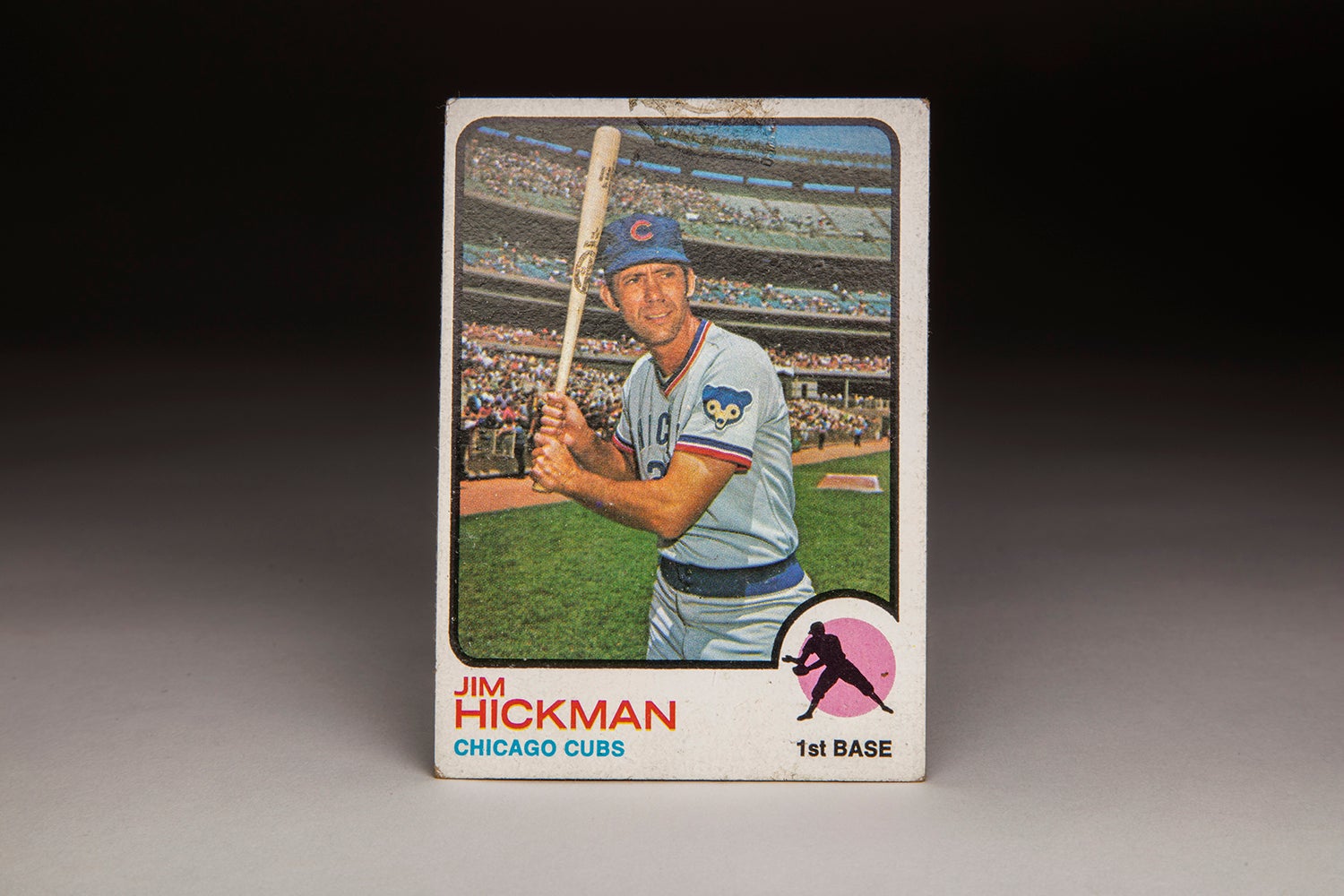

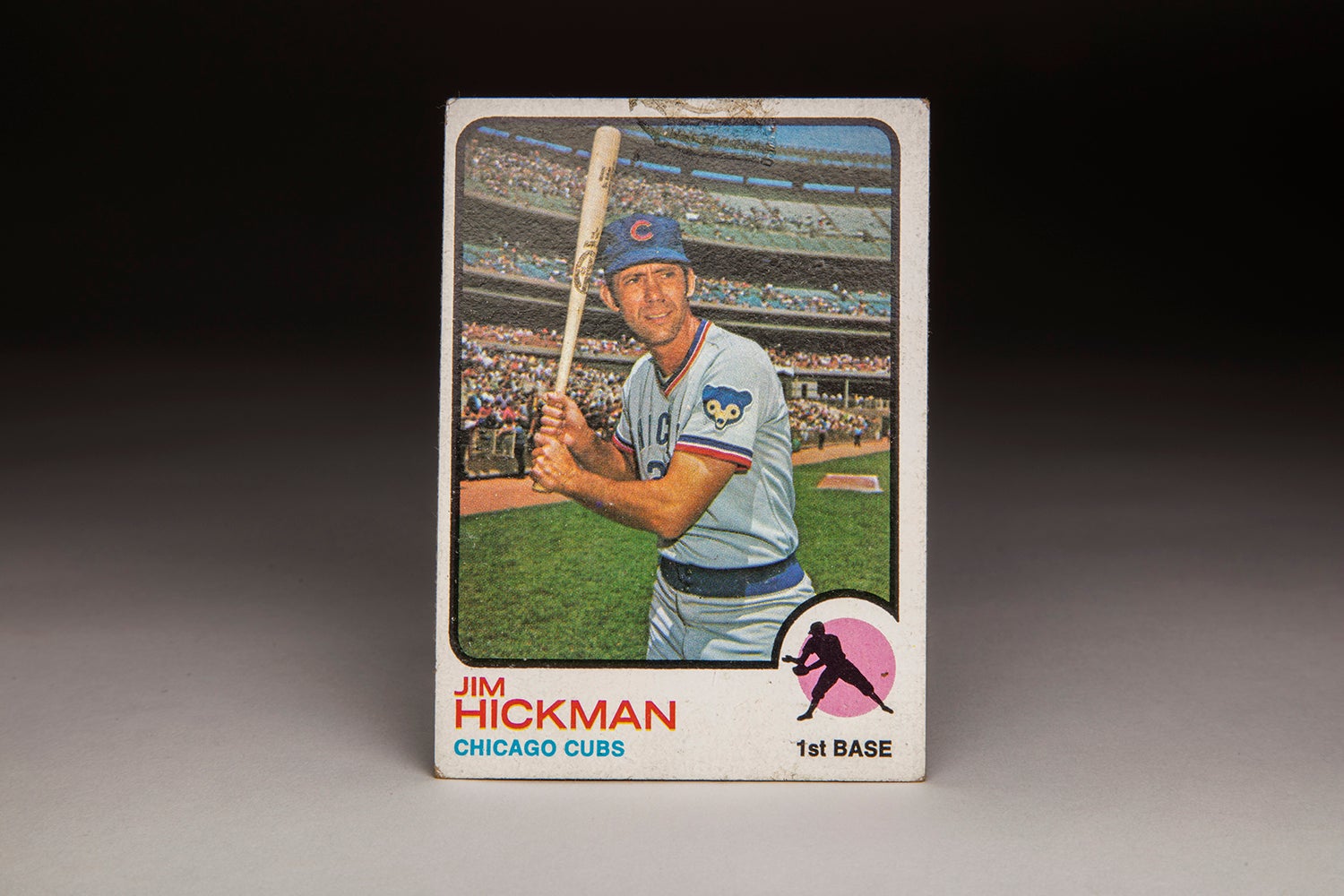

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Hickman

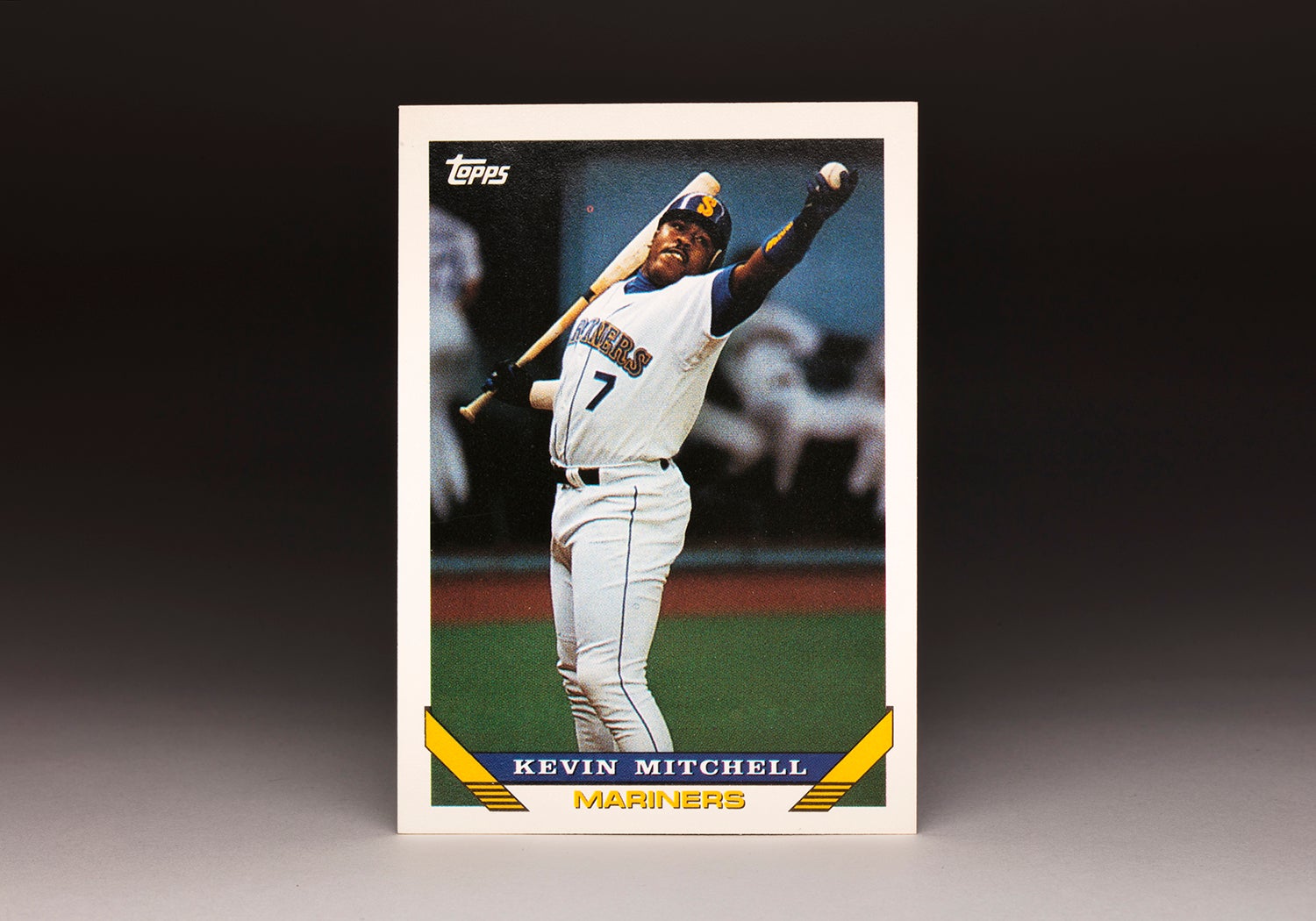

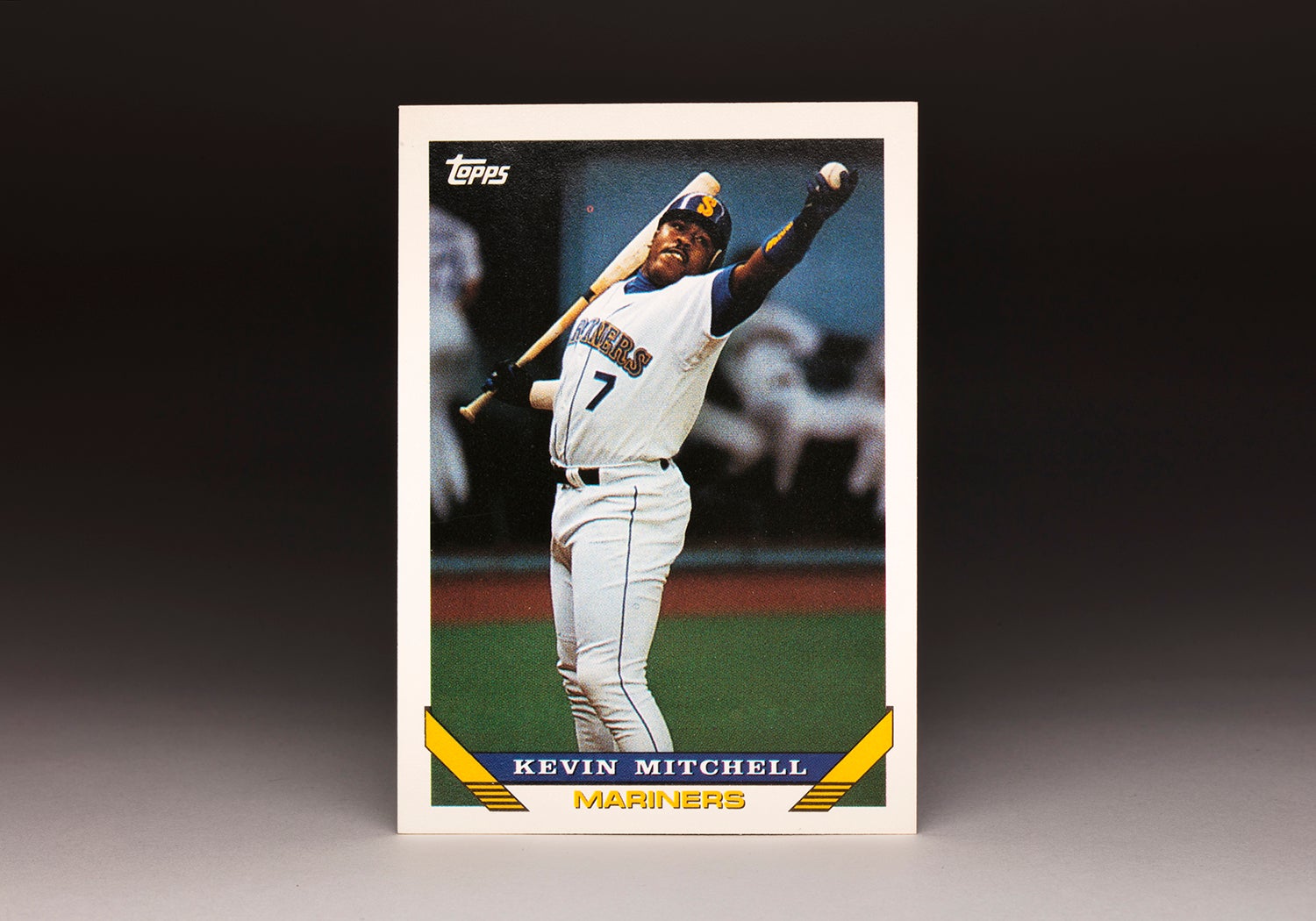

#CardCorner: 1993 Topps Kevin Mitchell

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bernie Carbo

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Hickman