- Home

- Our Stories

- Bat in the Night

Bat in the Night

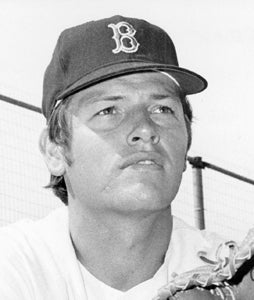

One of the most memorable games in postseason history took place in the 1975 World Series, a contest that came to its dramatic conclusion with a post-midnight swing in which the batter willed the ball fair.

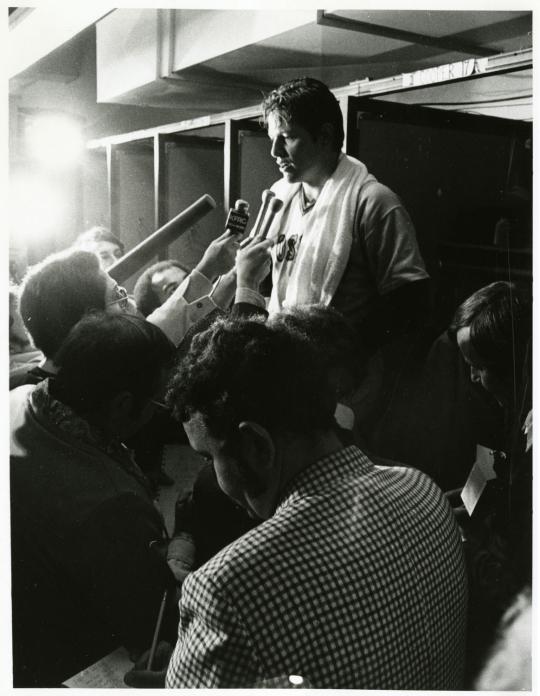

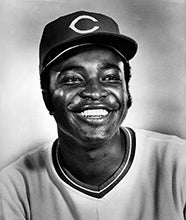

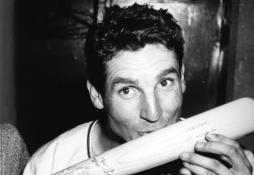

On Oct. 21, 1975, in Game 6 of the World Series, Boston catcher Carlton Fisk socked a walk-off homer on a 1-0 pitch leading off the bottom of the 12th inning that gave Red Sox a 7-6 victory over the Cincinnati Reds before a capacity Fenway Park crowd of 35,205. Using hand signals and body English to prevent his hit off pitcher Pat Darcy from going foul, the baseball ricocheted off the left field foul pole while euphoric fans poured on the diamond from the stands as Fisk rounded the bases and the Series headed to a seventh game.

It’s a moment that will live forever in Cooperstown – retold in the Museum’s Whole New Ballgame exhibit.

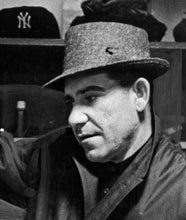

“Fisk’s reaction was the greatest individual replay we’ve had in World Series history,” said the game’s director, Harry Coyle, who had handled almost 30 Fall Classic broadcasts at that point for NBC dating back to 1947. “It tops [Yogi] Berra leaping into the lap of [Don] Larsen after the perfect game.”

According to Fisk, he turned to teammate Fred Lynn, who was batting fifth in the order behind Fisk this game, before his leadoff at bat in the 12th inning and said, “I’m going to hit one off the wall and it’s up to you to bring me home.” But Darcy, the last of eight pitchers for the Reds this game who had pitched two scoreless innings, made the conversation irrelevant when he allowed the Fisk round-tripper.

“The pitch was a sinker, down and in. I knew when I hit it that it would be either a foul or a homer. I thought it was going to hook around the pole, but it hit the pole,” said Fisk, elected to the Hall of Fame in 2000, in the clubhouse after the game. “I knew the wind was going out. Actually, the tricky wind pushed my hit about 15 feet toward the foul pole. The wind always does that here.

“I also knew that fans were going to be everywhere on the field. My main thought then was to make certain to touch every base regardless of the confusion out there. I said, ‘I’m going to run like O.J. Simpson, and I’ll touch those bases no matter who I have to stiff arm.’”

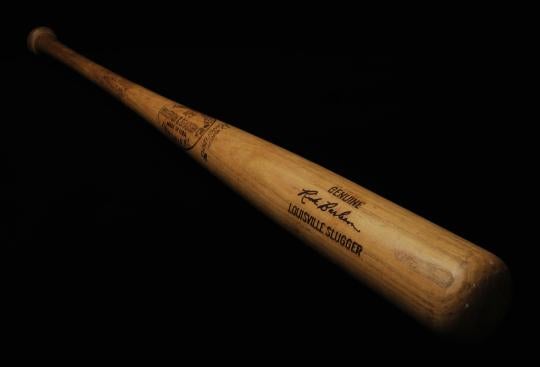

The bat Fisk used that night – a Louisville Slugger 34 inches long and weighing 30 ounces – was a Rick Burleson model two ounces lighter and a half-inch shorter than that catcher’s usual bat. Fisk, who also used the bat in Game 7, was attracted to this new piece of lumber from his team’s shortstop as the game wore on because it was lighter and easier to control.

Other Boston Game 6 highlights included outfielder Dwight Evans’ acrobatic catch of Joe Morgan’s drive to right field in the 11th that turned into a double play and Bernie Carbo’s dramatic three-run pinch-hit homer with two outs in the eighth that created a 6-6 tie.

“It was a fantastic game,” said Fisk, the 27-year-old native of Vermont, of the game postponed three days by rain. “You’re not exactly on top of the world when you’re trailing a club like the Cincinnati Reds, 6-3, with four outs to go. Pete Rose came up to me in the 10th and said, ‘This is some kind of game, isn’t it?’ And I said, ‘Some kind of game.’

“Look, you’ve been hearing about Johnny Bench for five years or so. But tomorrow you’re gonna be reading about me.”

The game took four hours, one minute to complete, the longest game, time-wise, in World Series history up to that point. With Tuesday night becoming Wednesday morning, the clock read 12:33 a.m. when “Pudge” hit his shot smack against the yard-wide yellow mesh attached to the inside of the left field foul pole near the Green Monster. Soon, Fenway Park organist John Kiley was playing “Stouthearted Men,” the “Hallelujah Chorus” and “The Beer Barrel Polka.”

“And all of a sudden the ball was there, like the Mystic River Bridge, suspended out in the black of the morning,” was the lead paragraph 2004 BBWAA Career Excellence Award winner Peter Gammons wrote in the next day’s Boston Globe.

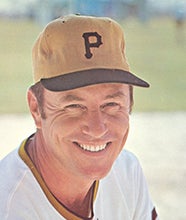

Gammons’ colleague at the Boston Globe, columnist Ray Fitzgerald, called it the best game ever, surpassing Game 7 of the 1960 World Series in which Pirates second baseman Bill Mazeroski’s walk-off homer in the bottom of the seventh inning gave the Bucs the championship over the Yankees.

“Now, the Mazeroski game is No. 2,” wrote Fitzgerald. “Last night was a Picasso of a baseball game, a Beethoven symphony played on a patch of grass in Boston’s Back Bay.”

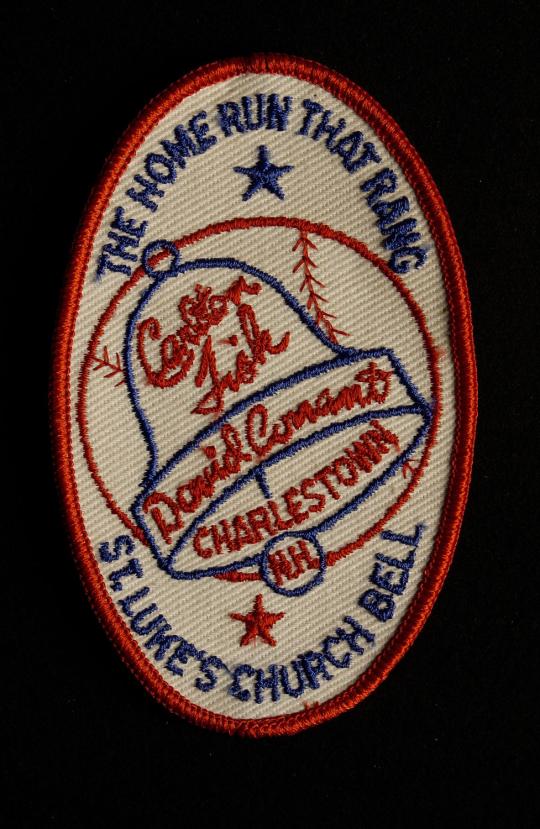

With a national television audience of 50 million or so, the climactic shot heard around the baseball world even led to church bells being rung in Charlestown, N.H., where Fisk’s parents lived. David Conant, who rang the bells in the Episcopal Church after the game, said the noise woke up the minister, who thought the bell ringing “was a hell of an idea.”

“Until this one, I thought the extra-inning game we lost in Cincinnati (a 6-5 loss in 10 innings in Game 3) was as emotional as we could get. The stage was set for everything, though, in this one,” Fisk said. “We knew the Reds weren’t going to blow us out of the park and we knew we weren’t going to blow them out. Everyone was emotional.”

The Reds would capture their first World Series title in 35 years the next day with a 4-3 win.

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum