“It took just seven hours to print… the book, but a year and a half to tell the computer what to do.”

Books of Numbers… and Stories

I have been crazy about baseball, particularly its statistics, since the age of 10. I started by watching games on my family’s black and white television set, collecting and studying Topps baseball cards, and reading everything I could find about the game and its rich but scattered history. In 1967, it seemed that one had to piece together information from these various sources to get anything resembling the full picture.

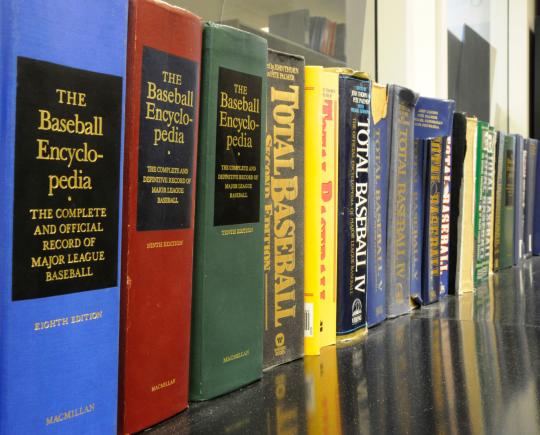

At 16, I was introduced to the secret “reference room” of my high school library. I riffled through the card catalog, wondering if there could possibly be any book about baseball which I hadn’t yet read or discovered. I came across an unfamiliar listing – The Baseball Encyclopedia – and walked over to section 796.357 to find it.

I hardly left the library for the rest of my high school career.

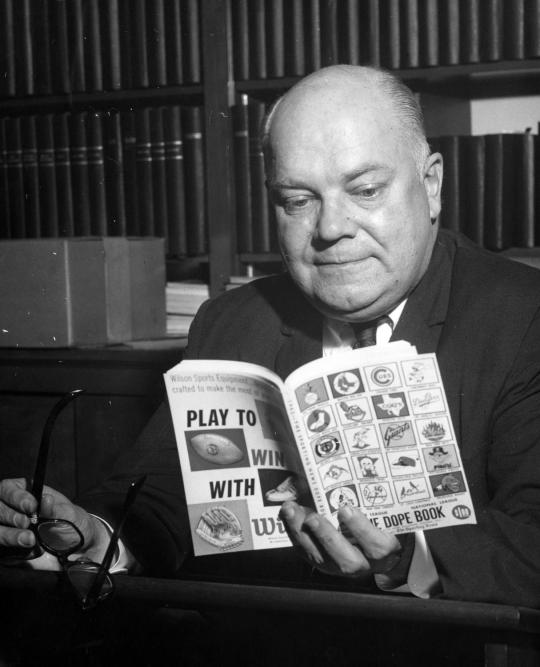

The Baseball Encyclopedia was developed by Information Concepts Incorporated (ICI), an early computer systems company. ICI, directed by David Neft, enlisted the services of Lee Allen, Historian for the Baseball Hall of Fame, and researcher/collector John Tattersall, and built a data-base from published box scores and game accounts dating back to 1876. Other key contributors included Robert Markel of The Macmillan Company, Systems Manager Neil Armann, and Associate Editor Jordan Deutsch. Dozens of other researchers and programmers did the grunt work, including recreating stats which weren’t recorded throughout history (e.g., pre-1913 ERAs, pre-1920 RBI, and pre-1969 saves, not to mention pinch-hitting and relief pitching records).

As Neft said, “It took just seven hours to print… the book, but a year and a half to tell the computer what to do.”