- Home

- Our Stories

- Sol White helped change the face of baseball

Sol White helped change the face of baseball

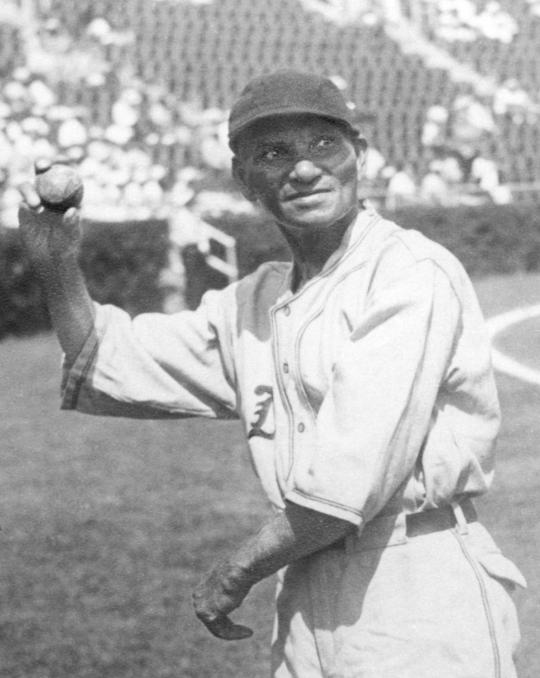

Though he was not permitted to excel on the diamond at the highest levels – due to the color of his skin – Sol White’s position in history is secure, thanks to his tireless work as a chronicler of the pioneering years of Black baseball.

From the mid-1880s until the early 1900s, many considered White one of the game’s great talents – a hard-hitting infielder who shined as one of the few African-Americans in the “white” organized baseball minor leagues and later, after a so-called “color barrier” was instituted, a star on a number of Black baseball’s most dominant teams.

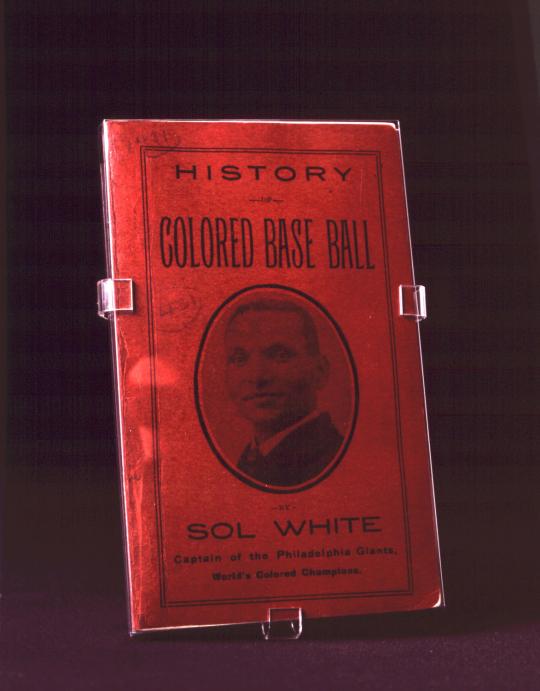

But in 1907, with the publication of the seminal “History of Colored Base Ball,” a record of Black baseball up until that point in time, that White’s multitalented role in the national pastime took on unique significance.

Born on June 12, 1868 in Bellaire, Ohio, King Solomon White made his professional baseball debut with the Pittsburgh Keynotes of the National Colored Baseball League in 1887. Soon, though, the 5-foot-9, 170-pound second baseman was starring with Wheeling of the Ohio State League, his first of five seasons playing in the integrated minor leagues, and batted .370 in 227 at-bats.

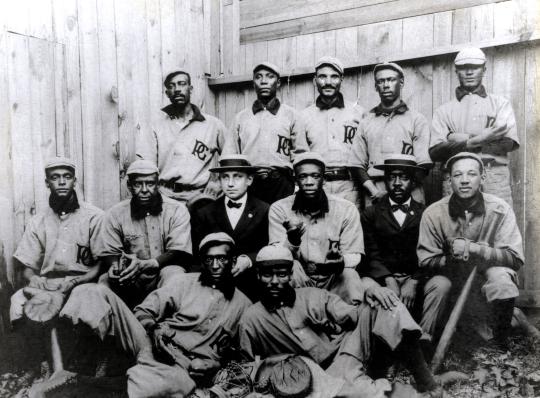

While the color of White’s skin prevented him from lasting long in the minors, he was now an established ballplayer and soon excelling in the years before the Negro Leagues with a number of prominent barnstorming Black teams, including the New York Big Gothams, the Cuban Giants, the Page Fence Giants, and the Cuban X-Giants. It was when he was with the X-Giants, in the mid-1890s, that he enrolled in Wilberforce University in Xenia, Ohio, during the off-seasons.

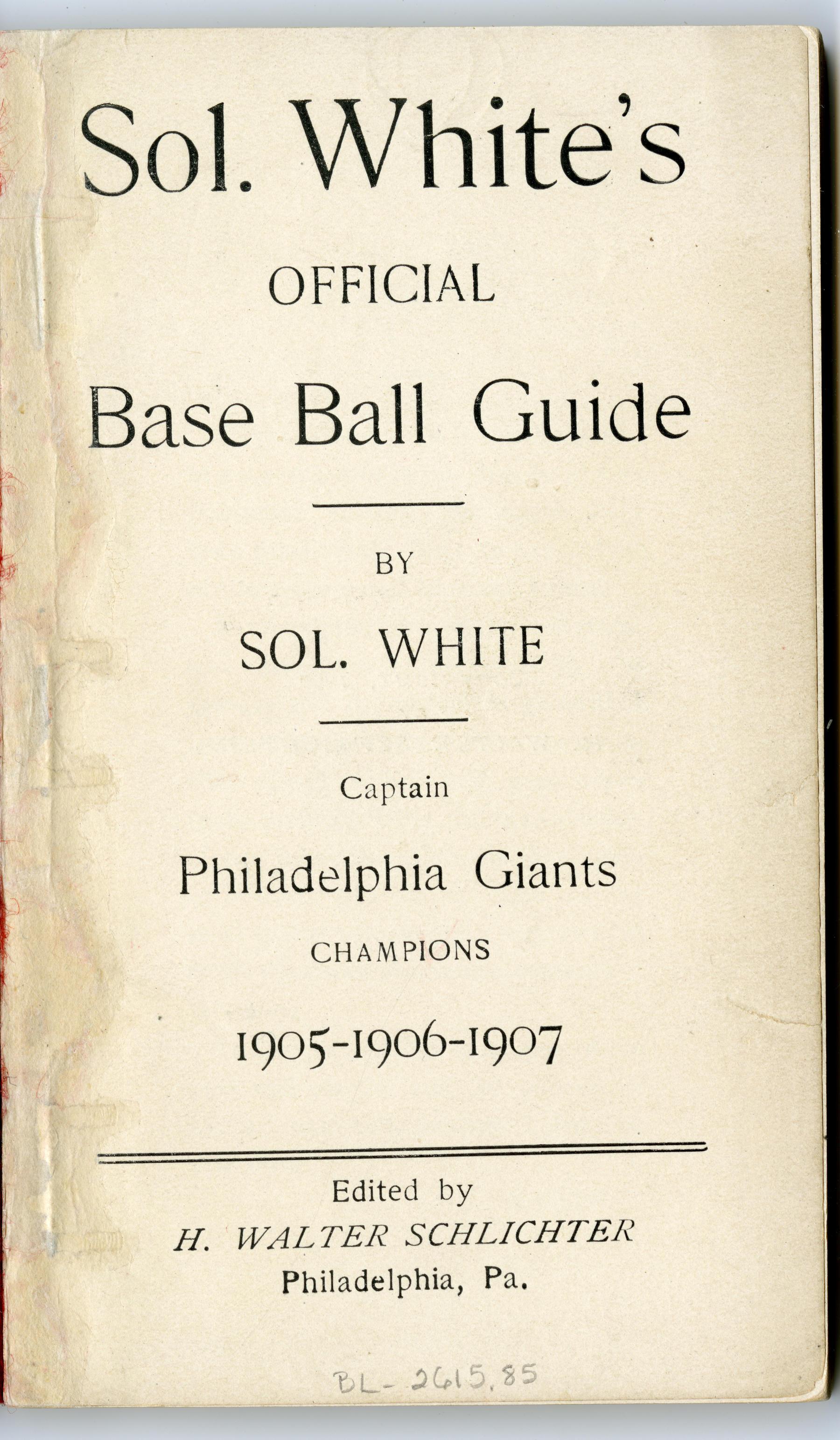

It was during the time White helped create the great Philadelphia Giants, a team he co-owned, managed and played for from 1902 to 1909, that his literary ambitions came to fruition. With 128 pages over the dimensions of 5 ¾ inches by 3 ½ inches, the “History of Colored Base Ball,” the title page reading “Sol. White’s Official Base Ball Guide,” has proven an invaluable historical resource.

The book’s contents include decades worth of Black baseball history, relevant box scores and almost 100 photographs of individuals and teams related to the history of an almost forgotten game. Besides the numerous advertisements for hotels, restaurants, pool parlors and saloons, mainly located around the Philadelphia area, there are pieces titled “How to Pitch” by Andrew “Rube” Foster, “Art and Science of Hitting” by Grant “Home Run” Johnson, and “The Color Line” by Welday W. Walker, along with the poems “Casey at the Bat” and “When Casey Slugged the Ball,” as well as articles penned by White called “Colored Base Ball as a Profession,” “Managers Troubles” and “Colored Players and the League.”

"History of Colored Base Ball," by Sol White, Captain of the Philadelphia Giants. BL-2615.85 (Milo Stewart, Jr. / National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Share this image:

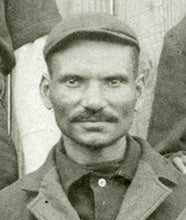

Sol White of the Negro Leagues - BL-2276-73-crop (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Share this image:

In White’s preface for the book, he writes, “Since the advent of the colored man in base ball, this is the first book ever published wherein the pages have been given exclusively to the doings of the players and base ball teams.

“Realizing the great progress made, and the interest displayed by the players and the public in general, I have endeavored to follow the mutations of colored base ball, as accurately as possible, from the organization of the first colored professional team in 1885, to the present time, in the trust that it will meet the approbation of all who may peruse the contents of this book.”

In a 1984 reprint of the book, longtime baseball broadcaster Red Barber, who along with Mel Allen was the first recipient of the Ford C. Frick Award in 1978, wrote in a new introduction: “White called this book an ‘Official Baseball Guide,’ but it is an entertaining, as well as an historical, account of the Negro players who wanted to play baseball badly enough to struggle against discrimination, poor play, no schedules, no leagues, changing rules and changing team allegiances. It was baseball played the roughest possible way. Rough as a cob. Until I read this dispassionate book, I had no idea of what had gone on before I met Jackie Robinson and began broadcasting his achievements. Truly, those early Black players loved baseball. Had to love it.”

Jackie Robinson of the Brooklyn Dodgers famously broke down big league baseball’s color barrier in 1947, debuting to both acclaim and derision on April 15. Forty years earlier, White, in a piece in the book called “Colored Base Ball as a Profession,” wrote, “It should be taken seriously by the colored player, as honest efforts with his great ability will open an avenue in the near future wherein he may walk hand-in-hand with the opposite race in the greatest of all American games – base ball.”

White would also lament, in his “Colored Players and the League” story in the book, the injustice race held against ballplayers of color.

“Of the players of to-day, with the same prospects for a future as the white players, there would be a score or more colored ballplayers cavorting around the National and American League diamonds at the present time.

“As it is, the field for the colored professional is limited to a very narrow scope in the base ball world. When he looks into the future he sees no place for him on the Chicago Americans or Nationals (champions), nor the Athletics (American), or New York (National, ex-champions), even were he superior to Lajoie, or Wagner, Waddell or Mathewson, Kling or Schreck. Consequently he loses interest. He knows that, so far shall I go, and no farther, and, as it is with the professional, so it is with his ability.”

Today, original copies of White’s 1907 book are exceedingly rare, with only a handful known to exist, including one in the library collection of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

White’s career on the field as either a player or manager would last until the mid-1920s, but he continued to contribute as a writer for some of the top Black newspapers of his era, including the New York Amsterdam News and the Cleveland Advocate.

White died in August 1955 at the age of 87, having lived long enough to see Jackie Robinson make his major league debut.

In February 2006, it was announced that White, with a resume unlike almost anyone else in the game, was one of 17 candidates from the Negro Leagues and pre-Negro Leagues elected to the Hall of Fame by a special committee of baseball historians.

White’s bronze plaque in the gallery of the game’s greats recognizes not only his important role as an outstanding player and manager, but also his influential contributions documenting the early history of Black baseball, reading, in part, “Authored “Sol White’s Official Base Ball Guide” of early Black baseball teams, players, and playing conditions.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum