- Home

- Our Stories

- Allen turned bigotry off the diamond into success on it

Allen turned bigotry off the diamond into success on it

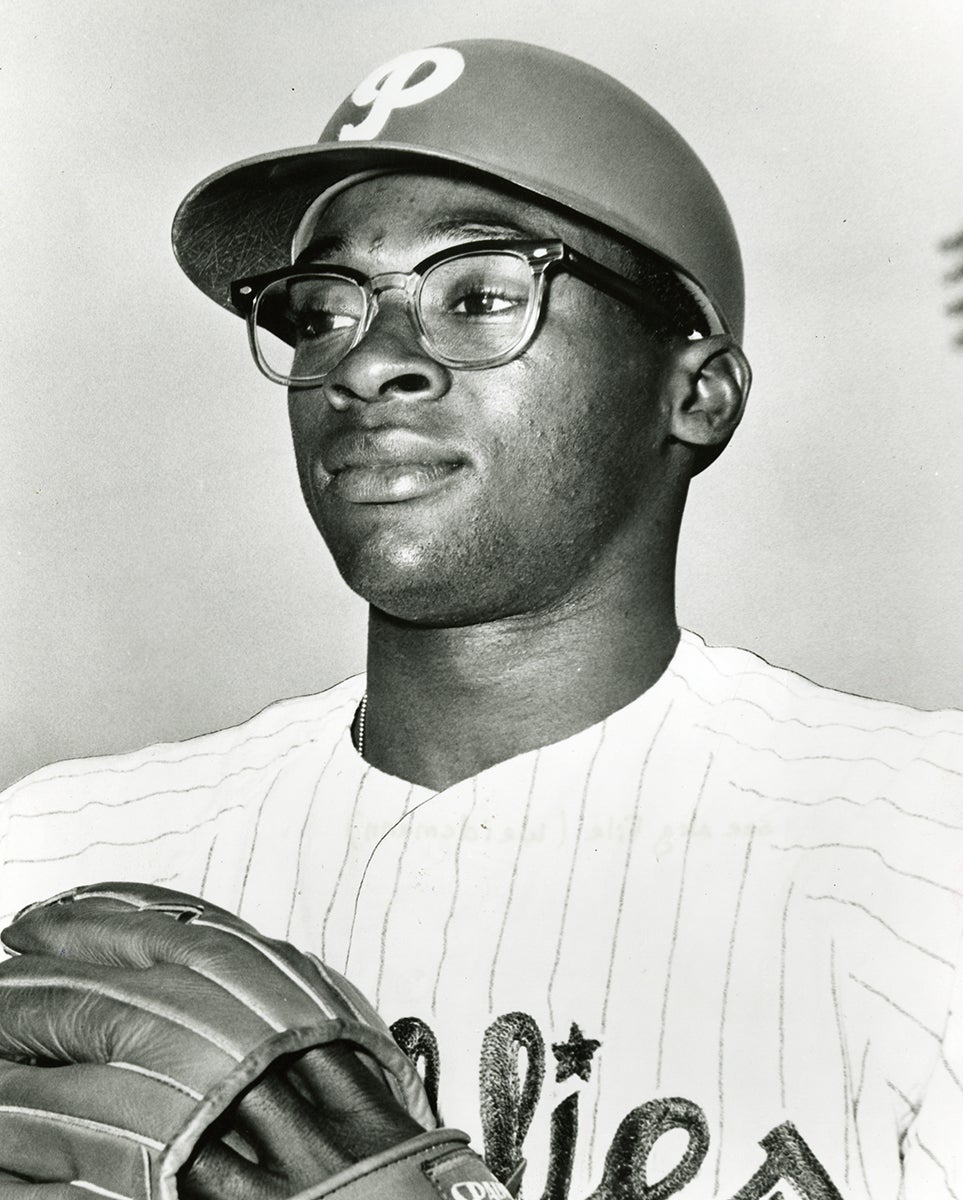

Few players in baseball history draw stronger reactions than Dick Allen. A talented and dominant slugger who has been praised by many of his teammates, Allen was a player whose career was often turbulent. Some of it was initiated by Allen himself, but much of it was fueled by a 1960s American culture that was filled with deep-seated racism and lingering Jim Crow segregation.

The starting point to the strife of Allen’s career can be traced to the 1963 season, the most difficult of his career. Thankfully, the harshness of 1963 gave way to a more pleasant 1964, culminating in a special night put on by his fans in Philadelphia. But then came more difficulties, principally a strained relationship with fans and management.

After signing with the Philadelphia Phillies in 1960, Richie Allen (as he was referred to by the media during his early career) spent three seasons playing in the lower minor leagues. In 1963, the Phillies made a change in their minor league structure. Moving their Triple-A team from Buffalo, N.Y., the Phillies relocated to the South, more specifically Little Rock, home of the Arkansas Travelers. With no advanced warning and little notice to the media, the Phillies decided to promote Allen to Triple-A and play him in Little Rock. That was no small task, given that Allen was about to become the first Black professional player in the history of Little Rock, a city that had housed pro baseball since the 1890s.

Little Rock, the state capital and the largest city in Arkansas, did not exactly toss out the welcome mat to Allen. After all, this was the same state where Governor Orval Faubus had refused only six years earlier to integrate the largest public school in Little Rock. With Faubus still in the governor’s office, little had changed in Little Rock’s social climate by 1963. In reaction to Allen’s assignment to the Travelers, a number of fans greeted him by marching in a protest parade. Indifferent to Allen’s immense talents, those citizens wanted no part of the first Black ballplayer in the city’s minor league history.

In an interview with sportswriter Milton Gross, Allen said he was completely unprepared for life in Little Rock.

“If I had lived in the South, I would have been used to it,” Allen told Gross. “But I’d never been down there and there I was, the first Negro to play at Little Rock, and it was killing me inside. It was eating out my heart. People were yelling things at me, and I couldn’t do anything back. People were on me all the time and I just had to stand there and take it.”

Allen had grown up in Wampum, Pa., a community known for being relatively free of racial strife. Little Rock provided the opposite end of the Civil Rights spectrum. On opening night in Little Rock, Governor Faubus, the noted opponent of integration, threw out the ceremonial first pitch. A crowd of 7,000 fans, mostly white, packed the ballpark. Some of the fans waved large placards that said, “Let’s not NEGRO-ize our baseball.” Fully aware of the message on those placards, and the general atmosphere of racial discontent, it’s no wonder that Allen, on the game’s very first pitch, dropped an easy fly ball hit to him in the outfield.

After that first game, Allen returned to his car in the parking lot. There he found the opposite of solace: a note on the windshield with a scribbled message, “Don’t come back again, n-----.”

Throughout the season, Allen would continue to be the recipient of abuse, both written and verbal. Allen heard racial taunts at the ballpark, made worse because they were coming from fans of the hometown Travelers. And on several occasions, Allen would make his way to his parked car, only to find another threatening note that made reference to his skin color and his unwelcome presence in Little Rock. In a 2009 interview with Bob Costas on the MLB Network, Allen discussed one of the worst incidents in Little Rock. He revealed that he once returned to his car to find that vandals had spray-painted the words, “N----- Go Home,” on the vehicle.

Away from the ballpark, Allen fared little better. According to his Society for American Baseball Research biography, while he visited stores in Little Rock, he was pestered by fellow customers who expressed their resentment. Policemen sometimes followed him on the streets of the city, questioning what he was doing. The harassing treatment became so persistent that Allen stopped walking by himself in Little Rock. While living with a black family in Little Rock, away from his teammates, he received death threats over the phone. At one point, he considered quitting baseball and heading back to Pennsylvania.

If not for some help from one of his teammates, Allen just might have left Little Rock. In an interview with Gross, Allen told the story of a player intervention.

“If it wasn’t for Joe Lonnett,” Allen said of the veteran catcher who played briefly for the Travelers that summer, “I don’t think I could have stayed at Little Rock. He came down with me and helped me.”

In contrast, Allen received almost no assistance from his manager. “Funny thing, I got more help from other people than I did from my own manager, Frank Lucchesi.”

Even in the face of isolation, mistreatment and bigotry, Allen persevered for the Travelers. He put up exceptional offensive numbers, hitting .289 with 33 home runs, 97 RBIs and an OPS of .891. He also led the International League in total bases.

Allen’s performance in Little Rock earned him a September promotion to the Phillies. On Sept. 3, he made his big league debut and went on to appear in 10 games for the Phillies, more than holding his own with a .292 batting average.

The following spring, Allen reported to the Phillies’ Spring Training camp in Clearwater, Fla. Manager Gene Mauch told Allen that he would make the team, but would play third base, a position that he had never played as a professional. Allen would have been more comfortable in the outfield or at first base, but those positions were already occupied by established veterans. Mauch wanted Allen’s bat in the lineup at all costs and saw third base as the best available option.

The new position did nothing to hamper Allen at the plate. On April 19, he hit two home runs in a game against the Cubs. Near the end of April, he lifted his batting average to .442.

Still, there were problems off the field for Allen, though they seemed less rooted in racism and more connected to other issues. In an interview with George Kiseda of the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, Allen complained about the Phillies’ insistence on referring to him as “Richie” on the team’s official roster, scorecards, and other printed material.

“To be truthful with you, I’d like to be called Dick,” Allen told Kiseda. “I don’t know how the ‘Richie’ started. My name is Richard and they called me Dick in the minor leagues…It makes me sound like I’m ten years old. I’m 22.”

In spite of his request, the Phillies, along with the Philadelphia media, continued to call him “Richie” until 1966, when some reporters began referring to him as “Rich.”

On the field, Allen continued to hit well during his rookie season, but struggled badly in making the transition to third base. He made frequent errors, on the way to a massive total of 41 miscues for the season. Instead of giving him slack as he learned a new position, the fans booed Allen severely in reaction to his fielding mistakes. Mauch did his best to defend a rookie learning a new position, but some fans continued to pound Allen with boos and catcalls.

As much as Allen became the target of fan vitriol, there were fans in Philadelphia who appreciated him and his on-field talent. In late September, the local business community organized an unauthorized “Richie Allen Night” at Connie Mack Stadium. It was done without any involvement by the Phillies’ organization and epitomized the support that Allen felt from the more knowledgeable fans (and business leaders) in Philadelphia.

That special night was a fitting reward for a player who put up remarkable first-year numbers for the Phillies. Allen batted .318 with 29 home runs, a .939 OPS and a league-leading 352 total bases. He took home the National League Rookie of the Year Award in nearly unanimous fashion, as he received 18 out of 20 first-place votes. He also finished seventh in the league MVP race, but likely would have placed higher if not for the Phillies’ late-season collapse in the pennant race.

Sadly, the appreciation the fans showed toward Allen that September did not last for long. The following season, after teammate Frank Thomas shouted Allen down with a racial slur a number of Phillies fans took the side of Thomas. At the ballpark, some fans shouted obscenities at Allen, including those of the racial variety. Some fans even took to throwing objects at Allen, including batteries and coins. The physical abuse remained such a threat that Allen began to wear a helmet in the field, a practice that he maintained for the rest of his career.

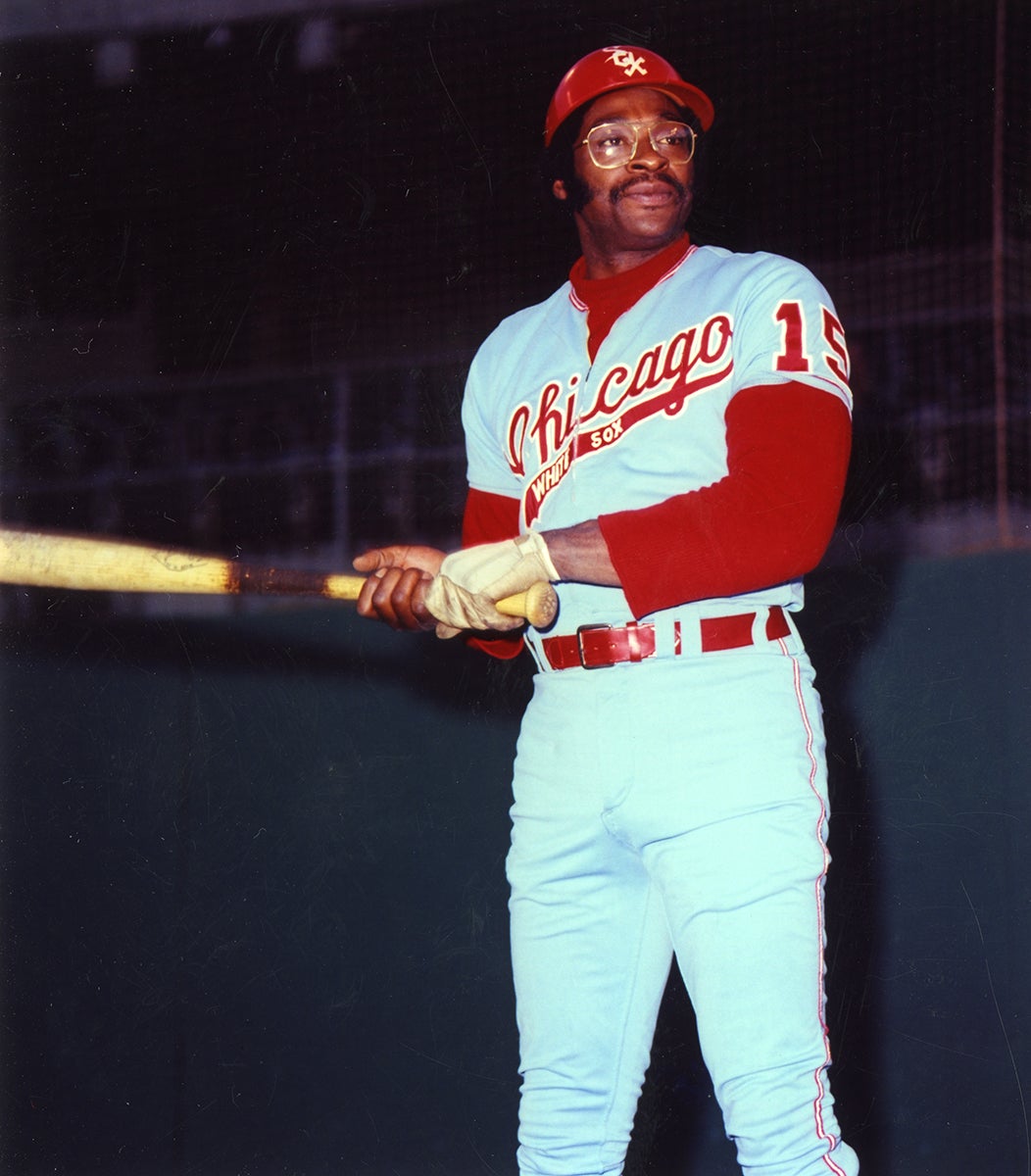

For the rest of his first tenure in Philadelphia, Allen’s relationship with the fans remained tense and uncomfortable. He also struggled with management, in part because of his tendency to miss the occasional game and the development of riffs with some of his managers. He would receive better treatment in later stints with the St. Louis Cardinals, Los Angeles Dodgers and Chicago White Sox (where he won the American League MVP in 1972), and even during a second tenure with the Phillies. By the last few years of his life, Allen’s legacy in Phillies history had changed completely. He had become beloved – a revered figure throughout Philadelphia and much of Pennsylvania.

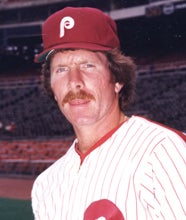

But for a long time, the events that took place in Little Rock and during those early years with the Phillies clearly left their mark on a man who felt the sting of being unaccepted. As Hall of Famer Mike Schmidt, a teammate of Allen in the 1970s, once said: “Dick was a sensitive Black man who refused to be treated as a second-class citizen.”

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum